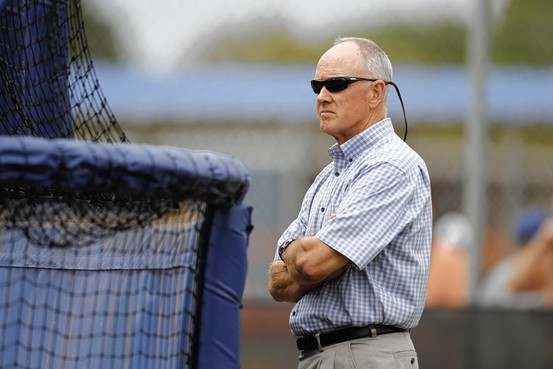

Evan Habeeb-USA TODAY Sports

As an undrafted free agent, Mike Bordick was happy for an opportunity in pro ball.

Coming off a strong junior season in which he hit .364 for the University of Maine, Bordick was hopeful that he would get a phone call from one of the 26 teams during the 1986 MLB Draft.

Though the Draft came and went without Bordick getting picked, he got the opportunity to continue playing over the summer in the Cape Cod League.

After just a few weeks of playing for the Yarmouth-Dennis Red Sox (along with future Hall of Famer, Craig Biggio), a young J.P. Ricciardi, who was a scout for the Oakland Athletics at the time, took a liking to the sure-handed middle infielder and offered him a contract with a 24-hour window attached.

Bordick signed and worked his way up the Athletics’ minor league rungs, reaching the majors in a limited capacity in 1990, after the lockout was lifted.

In 1992, Bordick played in his first full major league season, appearing in 154 games while splitting time between second and short. Bordick hit an even .300 and recorded a 4.3 bWAR (third-highest on the club) for the first-place A’s.

Following the 1996 season, Bordick signed a three-year deal with an option with the Baltimore Orioles to take over at shortstop for future Hall of Famer Cal Ripken Jr. In his three full seasons with the O’s from 1997-1999, Bordick played 462 games at shortstop for a total of 3,928.2 innings. Only Derek Jeter had more games and innings played at short in that span.

On July 28, 2000, the Orioles and New York Mets agreed to a trade, with New York sending Pat Gorman, Leslie Brea, Mike Kinkade and Melvin Mora to the O’s for Bordick. The Mets had been without their own slick-fielding shortstop in Rey Ordóñez since late May with a broken left forearm and were looking for an everyday replacement for the three-time Gold Glove winner.

In 56 regular-season games with the Mets in 2000, Bordick slashed .260/.321/.365 with four home runs and 21 RBI. In his first at-bat with the Mets on July 29, he homered off Andy Benes in the bottom of the third inning in the Mets’ 4-3 win against the St. Louis Cardinals at home.

Between the O’s and Mets in 2000, Bordick posted career highs in home runs (20) and RBI (80), and made the All-Star team for the first and only time of his career.

Bordick re-signed with the Orioles after the 2000 season and set a major league record for most consecutive errorless games (110) and chances (543) by a shortstop in 2002. His .998 fielding percentage that year is a single-season record for a shortstop.

Post-retirement, Bordick, 56, has kept quite busy. He worked as an analyst for MASN covering Orioles broadcasts from 2012-2020, teaches and provides instruction at the Baseball Warehouse in Maryland and is the chairman for the League of Dreams, a non-profit dedicated to providing opportunities for individuals of all physical and mental capacities the chance to play baseball, softball and other sports.

What started with disappointment in not getting drafted in 1986, turned into a respectable 14-year career that saw Bordick accumulate a 26.8 bWAR backed by his impressive defensive acumen at short.

I had the pleasure of speaking with Bordick in January, where we discussed how he signed as an undrafted free agent in 1986, his time in New York, and thoughts on Buck Showalter.

MMO: Who were some of your favorite players growing up?

Bordick: I grew up in upstate New York and it always seemed like I was watching the Dodgers and Yankees on TV. Unfortunately, or fortunately, depending on how you look at it, I wasn’t a Yankees fan; I ended up being a Dodgers fan. My favorite players were Ron Cey, Davey Lopes, Steve Yeager, that group of Dodgers. I always loved that Dodger blue.

As I got a little bit older, my dad was in the Air Force, so we traveled around a lot. We ended up being forced to become Red Sox fans because we moved to Maine and you’re kind of isolated from the rest of the world up there. All you get is NESN. [Laughs.] Patriots, Celtics, Red Sox, Bruins, man. That’s all you get.

I loved Rick Burleson as a shortstop for the Red Sox, and of course, they had some pretty great players like Fred Lynn, Dwight Evans, and Jim Rice.

It was the Dodgers as a young kid and then when I got into high school certainly Carl Yastrzemski and that group of Red Sox were a lot of fun to follow.

MMO: You mentioned that your dad was in the Air Force. Was moving around as often as you did difficult for you? Especially in terms of playing sports?

Bordick: It wasn’t easy, I’ll tell you. Looking back on it I just remember some really hard times trying to make teams and going to a new town. It felt like every time we moved I was trying out for a new football team.

I remember my dad was always trying to give me encouragement. This one day, we were looking out on this football field, we had just moved, and I said, ‘Dad, these guys are pretty big.’ And he said, “Don’t worry about it. Tell the coach that dynamite comes in small packages.”

I went out there and that was the first thing I said. I had more success trying out for new teams in football than I did in baseball. I got cut when I was in middle school, we had moved down to New Hampshire. I ended up getting cut from my middle school team and thank goodness that the base had a baseball team, so I was able to play over the summer. That kind of stuff was hard.

You can become isolated but I think through sports I was able to throw myself out there a little bit and challenge myself. In a lot of ways, I think you become self-motivated in that regard in overcoming social challenges and trying to become part of a team with a whole new bunch of guys.

The longest we ever stayed in one place was three years, so you just start getting used to something and then off you go to a new place. It was definitely challenging and I think anybody that grew up as a military brat understands that, and really, in a way, appreciates it. You learn a sense of discipline, self-discipline for sure, and then you find ways to overcome those little obstacles that get in your way.

MMO: Did you mainly play middle infield growing up?

Bordick: As a young kid my dad was a catcher, so he always put me behind the plate. He was my coach in Little League all the way up until I got to high school. That was another thing, good or bad, but there was a long time when I really didn’t get along with my dad because I didn’t like the way he coached me. I felt like he was separating me from everyone else, and I just wanted to be part of the team.

I caught, pitched, played shortstop, and in high school, I played outfield a little bit. If you have a good arm, you’re always going to find your way on the mound, so I guess I moved around a little bit. It wasn’t until I got to college at the University of Maine that I played solely shortstop.

I asked the coach, John Winkin if I was going to do any pitching. He said, “No, I’ve seen you pitch. You’re going to stick at shortstop.” I was never as good as I thought I was. [Laughs.]

MMO: Defense was obviously your calling card in the majors, but was that something you were always gifted at? Or, was there a time that you can recall where your defense elevated to another level?

Bordick: I think I always had a little bit of a gift defensively, and I attribute that to playing other sports. Back when I was a kid if it was baseball season you played baseball. When the fall came around you threw your glove in the closet and you went and grabbed a football. When football season was over you grab a basketball or a hockey stick.

I was fortunate enough to play three sports up until high school and then I just played football and baseball. I think being a well-rounded athlete kind of helped me defensively with hand-eye coordination, the ability to understand pursuit angles of baseballs and the ability to read hops and use my feet correctly, which was probably the most important thing. Some of the best defenders have good feet, and I don’t care what sport you’re playing, they have good feet; they move well and they can anticipate.

I always had good feet and legs underneath me, but I became fundamentally sound, and where, I guess, I became a true defender was in college. At the University of Maine, we were indoors so much that the fundamentals were pounded into you every day. That’s where I learned that consistency and it carried over into pro ball.

For the longest time I was considered all glove, no-hit, and I think through more experience I ended up figuring out how to get the bat on the ball.

MMO: You went undrafted in 1986 and then played in the Cape Cod League where J.P. Ricciardi offered you a contract with the Oakland A’s. Can you talk about that time period to eventually signing with Oakland?

Bordick: The Maine program was really good. We had some guys that got drafted off our teams and we went to the College World Series five out of six years back in the early eighties. I got to go to two out of three years.

Maine was getting nationally recognized and in 1986 I was a junior and I put together a really good year; I hit .360, played good defense and we went to the College World Series again. I guess being so naïve I thought I was going to get drafted because I had seen my teammates get drafted.

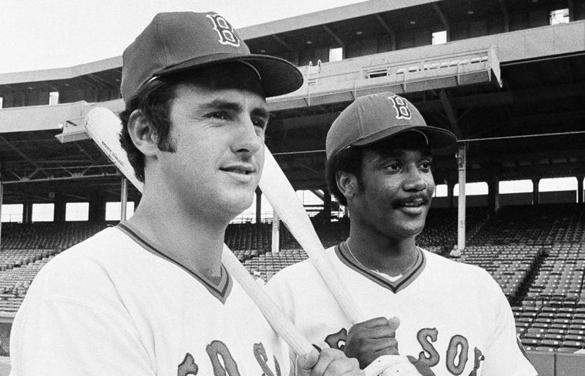

The Draft came and went, and there again I stepped back and thought, wow, I must not be good enough right now. My work ethic kind of pushed me through that as I got an opportunity to go down to Cape Cod. I was down there for a couple of weeks and had some great teammates. Craig Biggio was the catcher on our team for the Yarmouth-Dennis Red Sox.

I put together a pretty good weekend of baseball, I played some good defense and I may have gotten a hit. Hitting was a struggle down there and I remember Biggio and me going, man, we have to get over this Mendoza line! We were scuffling.

We were only down there for a couple of weeks and then J.P. Riccardi came over the fence one day and just kind of talked to me about an opportunity to sign with the A’s. He kind of put it out there and said, “We have a 24-hour window. There’s another kid that might be signing.”

I had to make a quick decision. I’m not saying it was the wrong decision, I contacted some people, those I trusted, and for the most part, they were basically saying it was a great opportunity to chase my dream. And that’s what I did.

The next day I went to J.P.’s hometown of Worcester, Massachusetts, signed the contract right in his uncle’s restaurant, and a couple of days later I was in Medford, Oregon, starting my professional career.

MMO: Sandy Alderson was the GM of the A’s during your tenure in Oakland. I’m curious what your impressions of Alderson were?

Bordick: I always had the utmost respect for Alderson and the A’s organization. First, they gave me an opportunity and from what I understand, I was more of a roster filler, like a lot of undrafted guys. The Draft comes and goes, and they’ve already got X number of guys on their rosters. If somebody doesn’t sign or gets hurt, they may need a guy to fill in the roster. That’s what I was in Medford, Oregon.

The A’s had shortstops up the wazoo; Walt Weiss had just been a first-round pick, he was on his way. The third-round pick my year was a shortstop named Darrin Duffy. They had a lot of shortstops in the organization but they kind of held true to their word, which was if you perform, you’re going to get opportunities and you’re going to climb the ladder.

I think you always need a sponsor, and I did. My first coach was Dave Hudgens, who’s the bench coach with the Blue Jays now. He was my first manager in Medford. The next year I had Tommie Reynolds in Single-A, and then I had Reynolds again in Double-A. Then Reynolds got promoted to the big leagues and in 1990 they had the lockout. When they came back from the lockout, they expanded the roster by two players.

Tony La Russa asked Reynolds, “Who do you trust to catch the baseball when I need him to late in the ballgame to help us through the first month?” And Reynolds, God bless him, threw my name out there and that’s how I made the team in 1990.

That goes right back to Alderson because if the organization isn’t constructed that way where they trust guys and push guys through, as an undrafted college guy they were saying here’s another opportunity. Make the most of it or you’re done. That’s how it goes. I climbed the ladder through the minor leagues and into the big leagues, I got a taste of it and that’s really all it took. I knew I wanted to play and the next year I was up for good.

I’ll always be forever thankful for that organization and Alderson and the way they really ran things. With La Russa at the helm, Alderson, the ownership, it was really unique, and I never came across that type of game plan and that type of cohesiveness really ever again. Their minor and major leagues were as top-shelf as they could get. I don’t know how that organization ranked, but I do know that they had a little dynasty going in 1988-90 going to the World Series.

To be a part of that organization, I just had a sense and a feel that they were if not the best, they had to have been one of the top organizations in the game.

MMO: You had a breakout season in 1992 where you appeared in 154 games, batting .300 splitting time between second and short. Is there anything you can point to for the success you had that season, other than increased playing time?

Bordick: It’s going to sound pretty weird but Doug Rader was our hitting coach, and it was really a game-changer for me. He really let me know what hitting was primarily about, especially at the major league level.

In spring training, Rader approached me and said, “Alright, Mike, you have great hand-eye coordination, we have to figure out your hitting.” He said, “When did you have the most success offensively?” And I said, ‘In Double-A I had a really strong year, I felt confident.’ He said, “What was your approach?” I said, ‘I had an open stance because that spring I talked to José Canseco, and I asked him why he opened up.’ He told me it was because he wanted to get both eyes on the pitcher just to see everything a little bit better.

I tried that, fell in love with it, and made the All-Star team in Double-A. It really wasn’t until the end of the year in Double-A that I kind of tapered off because our farm director, Karl Kuehl, came down. Suddenly now, I’m a prospect and they changed me completely. Kuehl said, “You can’t hit like that. That’s a power hitter’s stance.”

Being an undrafted guy and not taking responsibility for myself and saying, I’ve got to stick with what’s working, I was the organization guy. Okay, I’ll do whatever you say. I stood straight up and the next thing you know I forgot how to hit for the next three years.

Rader said before an intrasquad game, “Why don’t you take that open stance up and I’ll see how it looks.” I tried to go through my recall of how I stood and stuff like that, and I go up and hit a hard groundball to third base. On my way down to first base, in my head I’m just thinking, here we go again. Another hitting coach is going to completely try to recreate me.

As I made my turn back to the dugout I look up and there’s Rader. And he’s a monster, a big dude. His eyes were as big as his head and honest to God he looked at me and said, “We can work with that.” I felt like the Grinch where my heart grew and grew. [Laughs.] It was unbelievable! My confidence just skyrocketed just from him saying I can do that, we can work with that.

To this day, I just believe that if hitters believe, then they’ll have success. I think confidence is the only way you’re going to have success hitting at the major league level. If there’s any type of negative thought, you’re defeated, especially with these guys throwing 95 plus nowadays.

I was able to string some consistency together that year, had a really unique approach and it morphed into a more upright, but open stance. You probably don’t remember my open stance, but you probably remember Jay Buhner’s stance. That’s how I hit.

I had a vote of confidence from Rader and that’s all it took. I remember that year I went 0-for-24 at one point, and that’s when you start questioning things. I looked at Doug and said, ‘Doug, we have to figure something out.’ He looked at me and said, “Why? You’re doing great. You’ll find a hole. Trust me.”

The next at-bat I blooped a base hit and off I went again. To hit .300 in the big leagues, especially for me, is something I’m extremely proud of and to stay consistent through that whole year is something I’ll never forget.

MMO: The mental side of the game is truly fascinating and something I wish would be talked about more. That’s why you’re seeing teams hire mental skills coaches and offering more of those services now. It’s crucial for success.

Bordick: It really is. And that goes with every facet of the game. Defense, pitching, hitting. If you find a confident player, you’re going to find a successful player. When guys start looking defeated and they’re searching for stuff, it will snowball and it’ll be a rough year. There might be flashes up and down, but they just can never lock into that consistency and are doubting themselves.

I give lessons to kids that are eight or nine years old, and if you start throwing negative stuff out there to any athlete, they’re beaten. Sure, you need to instruct guys and this and that, but you’ve got to find ways to find some sort of positive message.

I remember one of my roving infield instructors Merv Rettenmund. You could go and have a horse shit round in the batting cage and come out and say, ‘Merv, what the heck am I doing?’ He would find a way to say, “Listen, your timing was great. Your lower half was awesome. Let’s work on trying to pull your hands inside a little bit.” Something to make you feel good; there had to be a positive interjection in there, yet make you think of let’s try this and take ownership and responsibly.

And to go hand-in-hand with that confidence, when players can take responsibility for their own actions, they become better as well, instead of depending on other people to tell them what they’re doing wrong. Become your own self-advocate and your own coach. Professional players have so many repetitions under their belt, let’s go! You’ve got 10,000 more swings than anybody else in the game, you know your swing and what works and doesn’t. Take ownership of it and you’ll be better for it.

MMO: I spoke to Bob Tewksbury, who was the mental skills coach for the Red Sox, Giants, and now Cubs, a few years back for Mets Merized. And to have a former player who succeeded at the highest level understand how to communicate proper techniques whether it’s visually, breathing, etc. is so important for players to be able to reset and refocus.

Bordick: Absolutely. Bob Tewksbury and I are pretty good friends. When he was with the Red Sox, I loved to talk to him about the mental side of the game. I think he’s a follower of Harvey Dorfman. Dorfman was the guy that really set the standard back in the day.

And there again, I think the A’s were cutting edge in that regard with the mental side of the game. Dorfman was there to pick up the pieces of guys. Dorfman was there to pick up the pieces and glue them back together again and get them off and going.

I have all of Harvey’s stuff, I still have a manual that I go to, I swear to God, almost every day. I look in it and find some nice motivational things and some mental strategies that I can share with some of the kids that I work with over at the Baseball Warehouse.

MMO: When you signed with the Orioles in 1997, you were taking over shortstop from Cal Ripken Jr. What was that situation like and did you have any reservations about taking over for a future Hall of Famer and fan favorite in Ripken?

Player’s Tribune

Bordick: Yeah, I did. I remember when I first got approached, my agent called me up and said, “Pat Gillick called, and he wants to set up a meeting. They’d like you to be the shortstop for the Orioles.” I was like, ‘Wait a second. Cal Ripken’s the shortstop for the Orioles. No way this is happening!’

That was my initial response. After talking with Gillick, it was like, “This is going to happen with or without you, and we think you’re the best guy for the job.”

I was a free agent that year coming out of Oakland, and there weren’t a lot of teams knocking down my door. The A’s hadn’t really contacted me. The Royals had some interest.

There were a couple of factors, and one was coming up with the A’s. I just loved the winning atmosphere. Going to the World Series in 1990 and then in 1992, I was a big part of an underdog-type team that made it to the playoffs. The Blue Jays ended up beating us and winning the World Series that year. Then the A’s went through new ownership and stuff like that, and I really had a hunger to get back on that winning circuit.

In my opinion, looking at the Orioles, they looked like they were about to start a dynasty. They had Mike Mussina, Scott Erickson. They just signed Jimmy Key. Eric Davis, Ripken Jr., Brady Anderson, Roberto Alomar, Rafael Palmeiro. Are you kidding me, man? Loaded, right? I was just thinking we’ll go to the World Series in 1997 and this could be a run of three or four years, and I want to be a part of that.

The winning really outweighed a lot of stuff, aside from the fact that I needed Cal’s blessing. Part of that deal was I just needed to talk to him. I didn’t need him to say, I want you to come to play shortstop, I just wanted to hear what his thoughts were. And I tell you right now, as a shortstop, you don’t ever want to not play shortstop. I knew that from Cal. He didn’t tell me that, but I just knew that as a fellow athlete.

But he said, “You’ve got to do what’s right for you and your family.” And I thought I did. I said, ‘Well, I want to come back to the East Coast, everybody is in New England up in Maine. We have a young family; they want to see their grandkids and I’d like to get back to the East Coast and I want to be on a winning team.’

And that was it. It wasn’t an easy decision by any means. When you have to make a major choice like that, you go through every possible scenario; the good, the bad, and the ugly. I just thought that the winning kind of took over and I said I accept this challenge and I went after it.

When I agreed to sign with the Orioles, we were going to have a press conference, and my wife and I had a layover, I think it was in Pittsburgh. I saw my picture on the front page of a newspaper, I think it was The Washington Post, and I was like, ‘Oh my gosh. Monica, come look at this!’ I showed her the picture of me, and I started reading the article and it absolutely buried me. It buried me. [Laughs.] It was like, there’s no way this guy’s going to come in and take the place of Cal Ripken Jr. I was like, wow, maybe this isn’t going to happen.

I called my agent and said, ‘Hey, man, I don’t know about this. They don’t really want me down here. I thought everyone was in agreement that it was okay to come down and play?’

I guess from a media standpoint, it might not have gotten off on the right foot. I did put some undue pressure on myself for the first couple of months of the season. I remember I was struggling offensively and Sam Perlozzo, the third base coach, put his arm around me and said, “Can you please just relax and have some fun and play the game?”

I had enough games under my belt and had been in some hot pressure situations before, so I did, I just started relaxing. I had a great second half of the season, got into the postseason, and I just felt for sure that we were the best team in baseball.

We ended up getting beat by the Indians, but it ended up being an incredibly fun year and it was a great team. The Yankees ended up coming into the picture and went on that dynasty run, and the Orioles couldn’t quite rebound. Of course, they went through some transitions too, but that year I thought Pat Gillick and Davey Johnson were going to be working hand-in-hand, much like Sandy Alderson and Tony La Russa with the A’s. And they both left!

It became a little dysfunctional, but we had great players for a number of years. We just couldn’t get over the hump and make it back to the postseason.

MMO: What are your memories from the July 28th trade that sent you to the Mets in 2000?

Bordick: It was really unique. I always thought I wanted to experience everything in the game, and being traded was certainly one of them. When guys started getting traded from the Orioles, the writing was kind of on the wall. The Orioles had just underachieved for the last three years so they traded Charles Johnson, Will Clark, everybody was getting traded.

I remember Mike Hargrove (manager) said, “Listen, you’re not going to get traded.” He kept putting my mind at ease. I guess it was the day before the deadline, and Syd Thrift (GM) called me into the office and said, “Congratulations, you’re going to the Mets.” I was like, ‘What do you mean congratulations?’ Some guys like to get traded and some don’t, and Baltimore had been my home.

Then I started thinking that this is one of these teams (the Mets) that really has a chance. All I could think about was there was a reason why they want me. And obviously, Rey Ordoñez had gotten hurt, but they think I can help them get into the postseason and make a playoff run.

I think all athletes have that inside to just have challenges and want to rise up to a challenge. That’s the way I looked at it and I straight-up loved those guys on the Mets. Robin Ventura, Edgardo Alfonzo, Mike Piazza, that list goes on and on. We had awesome pitchers in Al Leiter, Mike Hampton, John Franco.

It was so much fun and I always admired teams from New York. The Yankees, I know what kind of environment it is just going in there as a visitor, and thinking, it takes a special player, but it takes a special team to understand as a unit what you have to do to have success. You’re going to get bombarded from all sides and as much as they love you, people are also going to try and break you down because they enjoy that too.

That Mets team was together, they were a solid unit, played really well, and had an awesome run, man. Getting into the World Series was unbelievable. I get chills just thinking about that experience.

Now, did I do as well as I wanted to do? Hell no! I don’t think I did as well as I wanted to in my whole career. I got hit in the thumb in the postseason, I cracked my thumb (Game 1, NLCS), and that kind of set me back a little bit. Just the experience of going to the playoffs and playing against great teams. The Giants and Cardinals were awesome. And then to play the Subway Series? Man, when we used to travel back and forth from Yankee Stadium to Shea Stadium, they’d shut the whole freaking highway down for us! It was incredible! And people would be getting out of their cars, holding up signs, beeping. You want to talk about feeling like a rock star? Holy cow!

Playing for the Orioles in the nineties, they sold out every night. But there is nothing that compares to that experience in New York: the Yankees and Mets playing in the World Series. It just blew me away, man, every single day.

One of the coolest stories was, it was probably my first week in New York, and I’m sitting by my locker. I look over and Chris Rock and Jerry Seinfeld were sitting on our couch. In our clubhouse! I’m getting changed and suddenly Chris Rock says, “Hey Bordick. Hey Bordick!” And I went, ‘Hey, what’s going on?’ He goes, “You don’t get this shit in Baltimore, do you?” I went, ‘No, sir!’

It was awesome. I enjoyed that experience so much. I wish I came back. I ended up re-signing with the Orioles the next year, but that was an unbelievable experience. I thoroughly enjoyed the team, the guys, the city, everything about that experience.

MMO: You talked about the energy and excitement from the Mets fans that season. Shea Stadium would actually rock!

Bordick: Literally! Literally move, man. That was incredible. My wife came out of the stands after one of the World Series games, and went, “I thought the stadium was going to collapse. It was bouncing up and down!” That was intense.

MMO: Having only played in the American League up until that point, what were some of the adjustments you had to make after the trade to the Mets?

Bordick: It was different, it was really different. And that might’ve been the hardest thing. One thing I loved about my experience in the major leagues was just being familiar with fields, players and my pitching staff. I think there’s something to be said about that too. You just know more.

It was a tough transition going to different parks, learning different pitchers, learning my own pitchers, learning my own teammates as far as positioning and things like that. And there too, even coaching, I was a player that had a routine and if I didn’t do my routine, it just threw me for a loop.

If all of a sudden batting practice was canceled one day, I would force my infield coach to hit me ground balls and piss the grounds crew off. That’s just how my routine was. Going over to New York and the new coaching staff, I think there was some concern about me. I was a little older then and I think they wanted to make sure I didn’t wear down. So, they kind of limited my ground balls.

I remember Cookie Rojas just saying, “Okay, two more.” And I went, ‘What are you talking about? This isn’t your career; this is my career. This is what I do, man.’

I ended up getting upset and I had to get Mookie Wilson to hit me ground balls every day. That was a little bit different, so I had to adjust my routine, that’s an excuse maybe but I think baseball players get set routines. There was an adjustment there in the three months I was part of the Mets.

MMO: You hold the record most consecutive errorless games at short with 110. Can you talk about that streak and the impeccable defense you were playing during that stretch?

Bordick: It was fun, I will say that. There were a couple of plays along the way where I think I may have had a gracious scorekeeper. I had some awesome first basemen that were helping me out as well.

I think, much like the repetitions you get as a hitter, the same thing holds true defensively. I was fortunate to continue to be able to move out there in the middle of the diamond. You just see all the hops. The game kind of slowed down, let’s put it that way. I just felt really confident out there defensively.

Kind of a funny story about that streak was I was probably mid-way through, probably somewhere in the fifties, and we were playing in Houston. B.J. Ryan was pitching and there was a soft liner hit up the middle. I went to try and get the short hop and the ball hit the dirt and stayed low and went underneath my glove. Two runs ended up scoring.

I went to our PR guy and said, ‘We’ve got to get that changed. B.J. had a tough run and he did not need those two earned runs tacked on. We’ve got to change that to an error.’ The scorekeeper wouldn’t do it. The home guy wanted to give his guy a base hit with a couple of RBIs.

Well, wouldn’t you know it, when I ended my streak it was almost an identical ball in Toronto. It was a soft liner up the middle, I tried to get the short hop on the turf and it just stayed down on me and went underneath my glove, and the scorekeeper gave it an error.

MMO: I’ve read that you’re involved with the non-profit organization, the League of Dreams. What’s your involvement and what is it all about?

Bordick: Thanks for asking. The League of Dreams is as special to me as really anything. I got involved in it about sixteen years ago now. Frank Kolarek, who is a local legend, grew up in Catonsville, Maryland, approached me and asked if I would come out and help volunteer at one of his events.

He had just started this to help special needs kids – special needs of any kind – to play the game of baseball and softball. It’s volunteer-based, so there could be a baseball team out there helping kids in wheelchairs catch the ball, hit the ball, run the bases.

It’s grown and we’ve gotten some good sponsors like the Cal Ripken Sr. Foundation and The Children’s Guild in the Great Atlantic. I guess our best year was maybe 40 to 48 events through the course of a year. We give kids opportunities to play baseball and softball, and just recently we had an event over at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County that had soccer, baseball, the lacrosse team came out, the women’s soccer team came out and the baseball team came out as volunteers.

You just get an amazing impact not only with our kids with special needs but the volunteers, man. They take that stuff back into their community and have a better understanding and appreciation for what our kids with special needs are going through. It’s just a win-win. It’s very emotional for me and I love being a part of seeing this grow.

I think there are going to be more and more opportunities throughout the state and hopefully, we can expand to more of a national level. Hopefully, through more fundraising and sponsors, we can give every kid an opportunity to experience the great game and all games, really. We’ve gotten into CrossFit and into swimming. The League of Dreams is all-encompassing, and we just want all kids to enjoy what sport offers.

Here’s a quick example: We had a young man that participated in the League of Dreams. He had cerebral palsy and this was probably 12 years ago. I saw him the other day and he was the young man that spearheaded this last event at UNBC, he’s a student there. That’s the kind of stuff that’s so rewarding. Here it is, a kid that played in the League of Dreams as a special needs participant. Playing sports helps with leadership skills and building character, and he wanted to continue to push and make himself better. He went to a junior college and the next thing you know he’s in a four-year program studying psychology, and he’s the one that initiated our big event at UNBC!

That’s the kind of stuff, man. It blows me away. The impact that this stuff has on everybody. I’m so proud to be a part of it and I look to continue to see it grow and have an impact on more lives.

MMO: That sounds like such an amazing and rewarding organization. Expanding the League of Dreams to a national level would be the next step I suppose?

Bordick: Yeah, and we’ve done events in some other states. Frank Kolarek, his son is Adam Kolarek, who pitched for the World Champion Los Angeles Dodgers (in 2020), through some of the contacts we’ve had we’ve had some events in Arizona and California. We just look to have a more consistent kind of impact in more communities because it’s a proven program that can work at high schools, colleges, etc.

The Cal Ripken Sr. Foundation has built hundreds of fields of these wheelchair-accessible fields all over the country. We’re hoping to be able to utilize those fields one day.

MMO: You also mentioned that you give lessons at the Baseball Warehouse. Is that your facility or do you just teach there?

Bordick: I teach there. A couple of years ago, the owner, Matt Morris, asked if I wanted to start giving some lessons. I started up and I really have a passion for coaching; I went to school for education. Being part of the game, I learned so much from all the teammates and coaches I had.

I’m not saying I’m one hundred percent in love with where the game is today, but I do think the game of baseball offers so many other benefits. The true benefits of all sports are to teach character building, sportsmanship, how to work together as a team, the ability to set goals and become responsible and accountable for your actions. The true essence of sports, those are the kind of messages I try and share with some of the young kids that I work with, and even when I talk to parents.

There’s an incredible value to just playing sports, and of course, I have that passion for baseball. If I can impact one or two kids then it makes me feel good.

MMO: You were a broadcaster on MASN for the Orioles during the time that Buck Showalter was manager. With Showalter now managing the Mets, what can the fans expect from Buck as a manager?

Bordick: You’re going to get an extremely prepared manager. I think that’s the name of the game when you can find somebody that’s not going to get caught off guard or surprised by any situation the game can bring at you. Buck’s the guy.

He does an incredible job, or he did with the Orioles, of bringing the veteran guys together and having them be the true leaders. Buck isn’t one to stand in the middle of the clubhouse and bark out orders. He’s one to really let the leaders of his team take charge and kind of police it. He’ll make sure that they’re on the right page, he might have a couple of meetings with them, and when you get the players on board that’s really all it takes.

A lot of times, managers try to do too much and overmanage, and I think in a lot of ways that hurts players. I think when the players take charge and kind of police that clubhouse and make sure guys get up on their own, Buck’s really good at finding a way to do that.

He did it with the Orioles with players like Adam Jones, Nick Markakis, and J.J. Hardy. Man, he didn’t have to say a word! He knew that the veterans were going to be able to help the younger guys and get them to play winning baseball. And that’s what happened in Baltimore after so many years of darkness, he took them to the postseason a few times.

I don’t think that’s going to change. I think he’s going to have an immediate impact on how guys approach the game on a daily basis.

MMO: Thank you very much for some today, Mike. I really appreciate your fantastic insight.

Bordick: Thanks so much!

Follow Mike Bordick on Twitter, @MBordick

Check out more on the League of Dreams here.