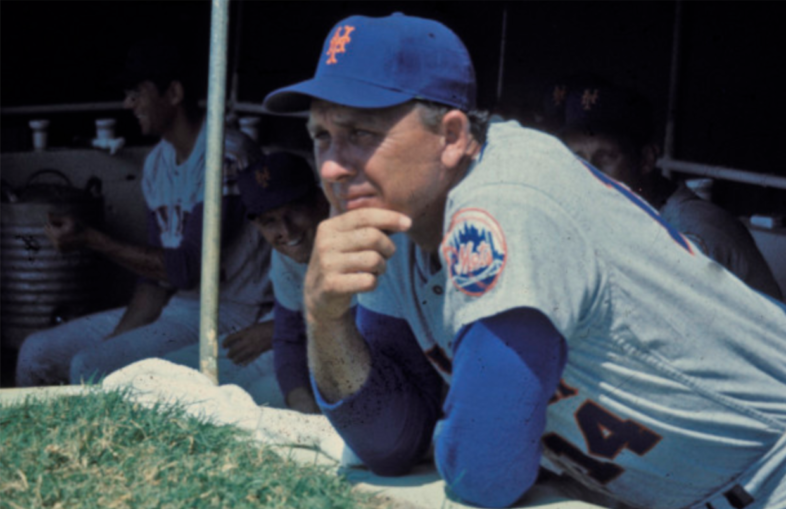

On April 2, 1972 Mets skipper and Gil Hodges passed away from a heart attack during spring training after playing a round of golf. He was two days shy of his 48th birthday.

Rob Silverman of MMO accurately wrote that Donn Clendenon was the final piece to the championship puzzle in 1969. Hodges was the first piece.

Hodges, who played 18 seasons (16 with the Dodgers, two with the Mets) and slugged 370 home runs, was named manager of the Mets for the 1968 season, taking over a team that had struggled since its inception in 1962.

The Princeton, IN native had managed the Washington Senators of the American League from 1963-1967, posting a 321-444 record over five seasons. In Hodges’ first season, the Mets showed notable, if not significant, improvement finishing with a 73-89 record.

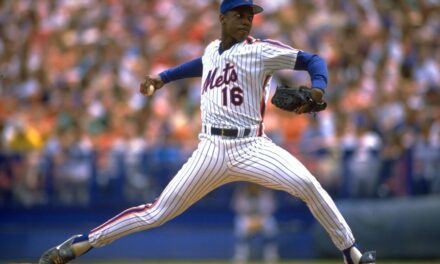

Beyond their record, the Mets had a pitching staff of young arms that was starting to come together. Tom Seaver won 16 games in 1968, and southpaw Jerry Koosman logged 19 wins. Fireballing right-hander Nolan Ryan was on the staff, along with fellow righty Jim McAndrew.

After 1968, it seemed better days were ahead for the guys from Flushing, how quickly those better days came shocked the baseball world.

Mets’ shortstop Bud Harrelson famously said that Hodges watched the 1968 team as if he were studying for an exam. Hodges, the former Marine who was honored and decorated for heroism recognizing his service in World War II, developed a strong sense of what he had and did not have on his ball club, and used that information to help deliver a championship the following season.

In an article from Radio.com, former Met Ed Kranepool recalled Hodges’ style as a manager, where the manager’s Marine pedigree clearly came through:

“You know, he was a strict disciplinarian, but he was a great leader,” Kranepool said. “It’s because of his leadership that we really have changed everything around. We went from the last-place laughingstock to a championship team in ’69.”

Art Shamsky agreed with his former teammate.

“You know, you’ve got 25 personalities and you really have to deal with certain things,” he said. “But Gil was a very strong disciplinarian and when he talked, we listened.”

Many people point to “the Cleon Jones incident” as an example of Hodges’ focus on discipline, though the former left fielder said it was anything but. Resetting the scenario, in July of 1969, the Mets were being pounded by the Astros in a game at Shea Stadium.

Johnny Edwards of the Astros hit a ball down the line that went for a double, and the manager came out of the dugout to ask why Jones could not have held Edwards to a single. Jones told the story in article by Kevin Kernan of The New York Post:

Hodges asked, “Are you all right?”

“I said I’m fine. He said, ‘Do you think you could have held him to a single?’ I said, ‘No.’ I said, ‘Gil, look down.’

“When he looked down, his feet were under water and so was mine. It had rained pretty good that day. And we had had a talk in Montreal, a week or so before that. I had a bad ankle. It comes from my old football days and every now and then it would puff up on me.”

After the exchange, Hodges felt it was in Jones’ best interests to leave the game and not risk injury. Though a stern leader, Jones said his manager would never publicly embarrass a player. However, Hodges cleverly used the event to motivate his team.

“He had a plan and a purpose, and the plan and the purpose was, if I can go out and talk to Jones and when I’m hitting .350, maybe all these other guys will get the message,” Jones said. “And sure enough, it worked.’’

Indeed, whatever Hodges was trying to do on that July day, and during the entire 1969 season, day did work. The Mets ended their regular season with a record of 100-62, swept the Braves in the NLCS, and defeated the heavily-favored Orioles in the World Series.

In a sadly ironic twist of fate, as written on MMO by Joe D., the day of Hodges’ death he and some coaches met Expos’ outfielder Rusty Staub in church on Easter Sunday. The Mets had completed a trade for Staub, though the right fielder was not yet aware.

It’s a shame that they never had the opportunity to work together, as Hodges passed just hours later. Yogi Berra was named manager for the 1972 season.

The combination of Hodges’ playing career, managerial achievements with the Mets, and military service led to his long-awaited election into baseball’s Hall of Fame in December of 2021. Hodges had been passed over for the Hall of Fame for many years, and his getting the call delighted Mets fans and former Mets players.

In an article by Christian Red in Forbes, Jones put it this way:

“Well, it’s been a long and grinding road for the (Hodges) family,” said Jones, the 79-year-old former Mets All-Star left fielder. “I was tickled to hear about it, that he got in. My personal opinion? I thought that he should have been in years ago.”

“Every first baseman in America in the ‘50s emulated Gil Hodges,” said Jones. “When we think back to that particular time, with Campy (catcher Roy Campanella), Jackie (Robinson), Duke Snider, Pee Wee (Reese), all the big names, Gil was just as big and just as good.”

Ron Swoboda, who made the amazing catch in Game 3 of the 1969 World Series, added:

“Although Hodges’ baseball numbers fell a little short of classic Hall of Fame numbers, as a manager he lost a whole lot of years because of a second heart attack that took him,” said Swoboda, 77. “When you consider what a strong, and decent character he was, what he meant as a player in that (Dodgers) clubhouse, what he meant in our (Mets) clubhouse… I think all of us 1969 guys were over-the-top happy that Gil was voted in.”

While Hodges had the disciplinarian reputation as noted above, his ability to use his roster to its fullest potential was perhaps his greatest strength as a manager. Here’s Jones from the Forbes article:

“When you think about ‘69, you think about only four guys who were starters — that was (catcher Jerry) Grote, (shortstop Bud) Harrelson, (center fielder Tommie) Agee and myself,” said Jones. “Everybody else platooned. All of these guys were excellent teammates, and somewhere down the line, they contributed to winning.”

Gil Hodges had as much of an impact on the Mets ascension to champions as anyone else affiliated with the team in the late 1960s. Could the Mets have won another championship in the 1970s if he had survived? Of course, we will never know.

Rest in peace, Gil Hodges.