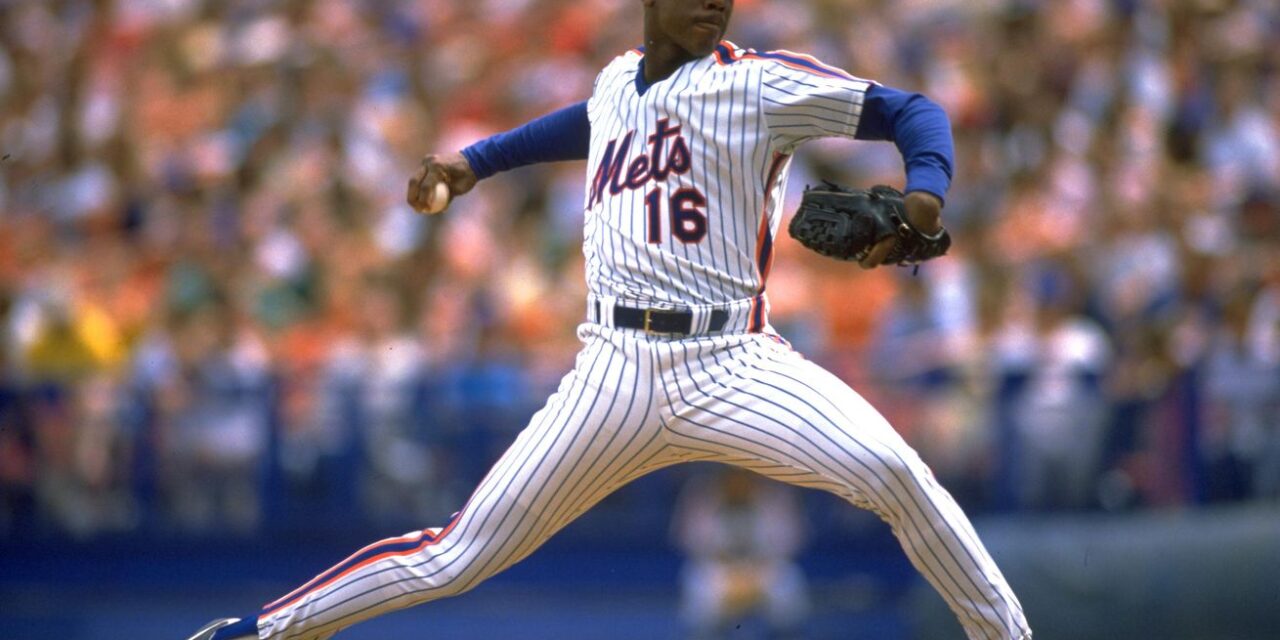

Forty years ago, Shea Stadium was the place to be—especially when Dwight Gooden took the mound. Never mind anything playing on Broadway—this was the hottest show in town.

Fans who were once avoided the park in Flushing, New York were now coming in droves to witness a teenager overwhelm elders with his fastball and fool them with a knee-bending curve that earned the reverential nickname, “Lord Charles.” Those who occupied a section in the left field corner put up “K” signs on the facade to mark each strikeout. There were a lot of them, too. A record 276 in a rookie season unlike any in baseball history, much less Mets history.

There is a direct correlation between the Tom Seaver trade in June 1977 and the moment when Shea Stadium, by every measure, went dark. Keith Hernandez and Darryl Strawberry supplied attitude and power when they arrived in 1983. But it was “Dr. K”—at age 19—who brought the electricity back.

Dwight Gooden.

On Sunday, Gooden will be center stage again as he deservedly gets his No. 16 retired at Citi Field.

The incredible start of his career gave reason to believe he was on the fast track to the Hall of Fame. His story has been told as a cautionary tale—one in which outside influences and internal demons stunted his astonishing talents and prevented him from achieving even greater accomplishments. But with passage of time, a better understanding of mental health and human frailties, plus his admittance to past personal faults, Gooden’s legacy is as a Mets legend.

He would go on to win 157 times and record 1,875 strikeouts over his 11 seasons. Those statistics, along with WHIP and ERA figures that are ranked in the top 10 of the franchise leaderboard, place Gooden alongside Seaver and Jacob deGrom on the short list of greatest Mets arms.

Gooden’s meteoric rise to stardom began in the spring of 1983, when the organization’s fifth-overall pick of a year before started the season with Single-A Lynchburg. By regular season’s end, he had tallied a Carolina League-record 300 strikeouts in 191 innings. By September, he had moved up to the Davey Johnson–led Triple-A club for the minor league playoffs and contributed as the Tidewater Tides won the minor league championship.

General manager Frank Cashen insisted Gooden remain in the minors to start 1984. Johnson, now promoted to take the reins of the big-league club, insisted his young pitcher make the jump with him. Davey won the argument. Before long, nobody was questioning that decision.

Within three months, Gooden was a local and national sensation, leading the league in strikeouts while barely old enough to vote. His starts at Shea were akin to rock concerts. Fans wanted to watch the teenage sensation as much as they wanted to watch the Mets.

Gooden became the youngest All-Star selection ever and proved he wasn’t fazed by the added spotlight. Doc struck out three straight American Leaguers and went two scoreless innings.

The second half for Gooden solidified his Rookie of the Year campaign. Over his last nine starts, he struck out 105 and had an ERA of 1.07. In two straight September outings, he had matching 16-strikeout, no-walk performances. The frequency with which Doc struck out hitters was unlike anything the public had seen. Just over 31% of batters Gooden faced went to the dugout as strikeout victims.

He compiled the game’s best strikeout per nine inning ratio this year: 11.4, which was an all-time record at the time. Of his 31 starts, 15 were double-digit strikeout performances.

If Gooden at 19 was a revelation, Gooden at 20 was nothing short of extraordinary. He went 24-4 with a 1.53 ERA and 268 strikeouts, giving him the pitching triple crown. He was the unanimous choice for the National League Cy Young and the youngest to ever receive the award. His ERA+ was a staggering 229 and his WAR was 12.2. Quite simply, it was the best season this franchise has ever had and of the best pitching seasons in major league history.

By August 25, he had as many victories as life years, becoming the youngest to reach that 20-win plateau. Over the last month of the regular season, while the Mets were battling the Cardinals for a division title, Gooden was up to the moment—not allowing an earned run in any of his September starts and delivering a complete-game victory against St. Louis on October 2.

It would have been impossible for Gooden to match this level no matter what the circumstances. Bright spots were mixed with dark days. He missed the World Series parade and started the following season in drug rehabilitation. Similar off-the-field issues would haunt him for the duration of his Mets tenure.

But for the remainder of the decade, he remained the ace of the New York staff—selected for four All-Star teams (twice named the starter) with a 114 ERA+ and 624 strikeouts over 796 1/3 innings.

Although he never won a postseason game, Gooden delivered several strong NLCS outings only for circumstances to prevent victories—often another dominant pitcher on the other side. In 1986, he was up against Astros ace Mike Scott in the opener and Nolan Ryan in Game 5. Two years later, a solid Game 1 in Los Angeles wound up a no-decision next to Orel Hershiser and a devastating ninth-inning home run in Game 4 thwarted Doc and the Mets’ hopes of going up 3-1 on the Dodgers.

Injuries began to surface in 1989. The toll innings at a young age reared its head. Gooden labored to a 9-4 record and an ERA that was a shade under 3.00 before shoulder discomfort put him on the disabled list—first for a couple weeks, then for a couple months. When he returned, Doc was relegated to relief appearances.

He had a healthy 1990 and reached the 200-strikeout mark for the fourth time, but a 3.90 ERA was the highest of his career. His 1991 season was derailed in August with shoulder stiffness that required rotator cuff surgery. The two-plus years afterwards showed Doc was a solid pitcher but a far cry from what he was in ’84 and ’85. Plus, the franchise was in serious decline.

Following another suspension for drug use, Gooden’s career in Queens came to an end. And while he pressed on with other teams in a series of comebacks and setbacks, he is forever a Met.

Each time he’s returned home, the cheers have been noticeably louder than just about any former player. When he came back for the Shea Stadium’s closing ceremony in 2008, his Mets Hall of Fame induction in 2010, and Old Timer’s Day in 2022, the outpouring of emotion are as much an acknowledgement of what he meant to the franchise as it is support for a player who has endured personal demons.

There’s no question Sunday will be a special day to so many. It’s been a long time coming. The cheers will be loud. In a way, it’ll feel like 1984 all over again.