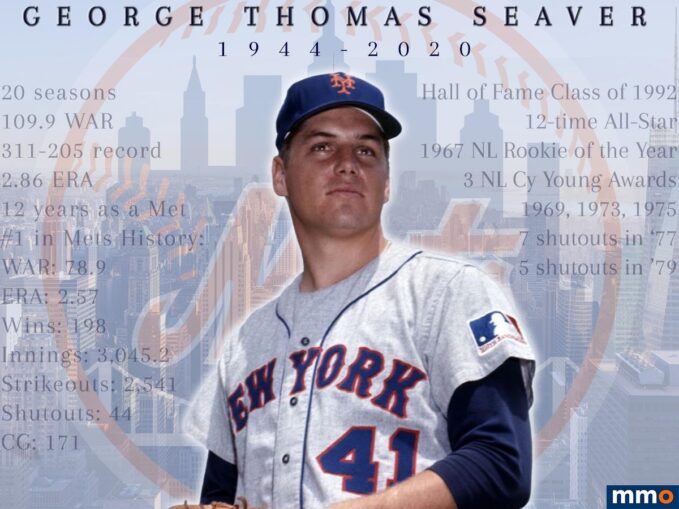

On this day in Mets history, 51 years ago, Hall of Famer Tom Seaver tossed his 19-strikeout gem against the San Diego Padres and set the major league record with 10 straight strikeouts to end the game. It happened on April 22, 1970 and our own Stephen Hanks was there. Here is the article he wrote back in 2010 to commemorate the 40th Anniversary of one of the greatest moments in Mets history. Please enjoy.

* * * * * * * *

There is a mantle above an unused fireplace in my home office that I’ve turned into a little shrine to my sports idol Tom Seaver. It’s nothing crazy, just a bunch of old action photos, vintage baseball cards, magazine covers, bobble head dolls, figurines depicting that classic Seaver right-knee scraping the mound motion, even an empty bottle of Tom Seaver recent vintage wine.

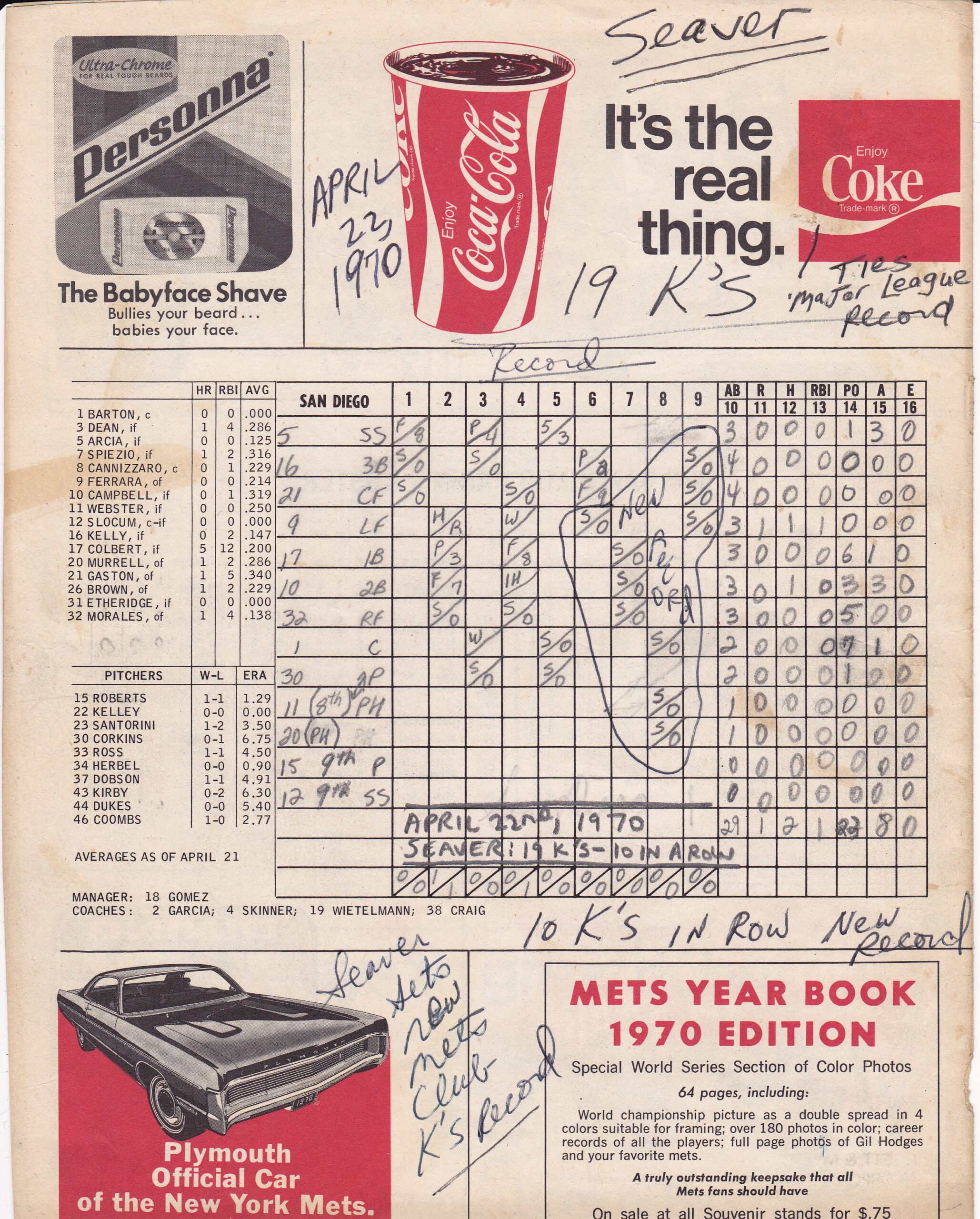

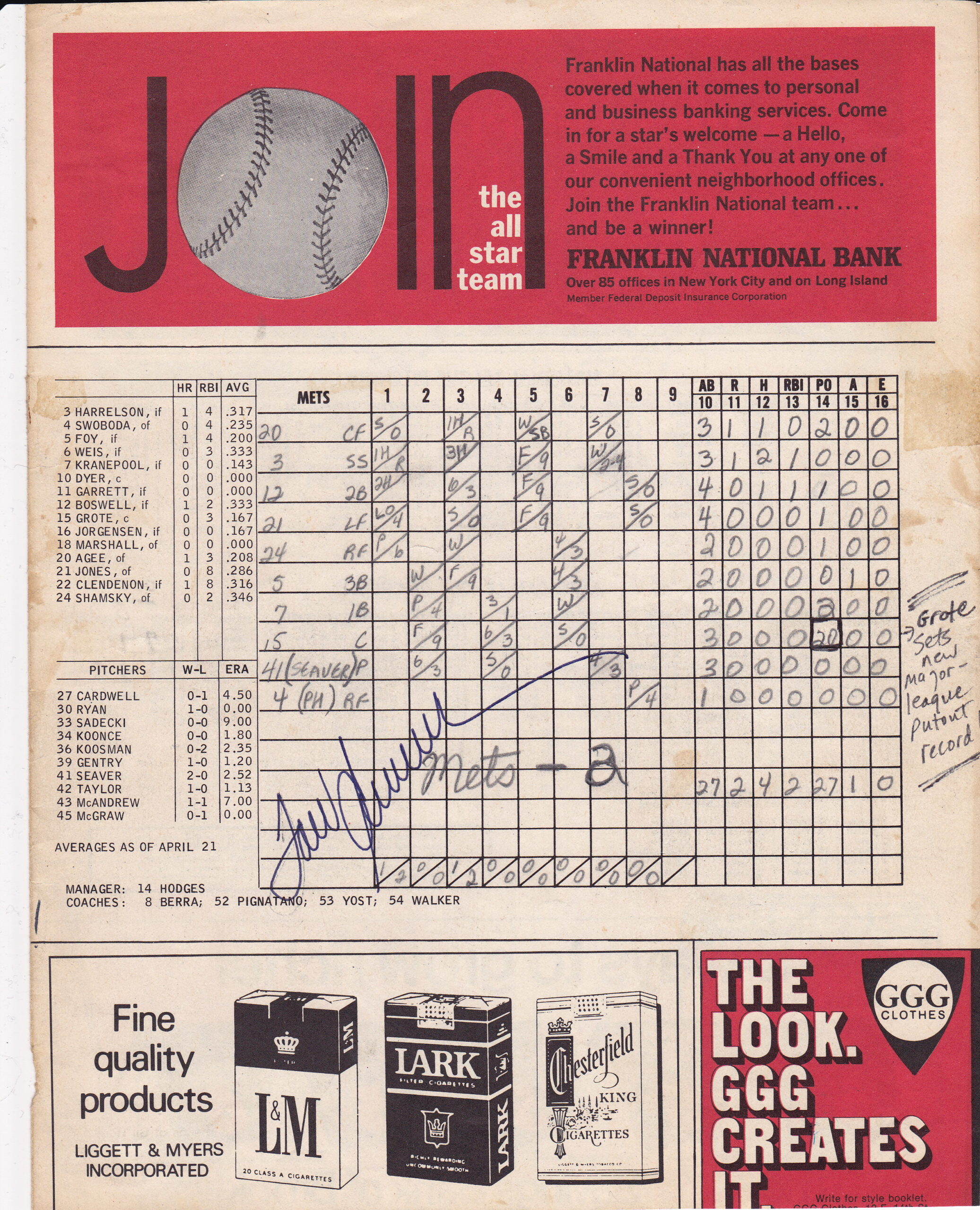

But among all these treasures, there is one that bears special significance today: the scorecard I recorded at Shea Stadium on April 22, 1970, the day the man I consider the greatest right-handed pitcher of all time (Roger Clemens forfeited that title the day he picked up a syringe) struck out 19 San Diego Padres, including the LAST 10 IN A ROW.

Here are both pages of my original scorecard. (click to enlarge)

It’s hard to believe it’s been 40 years since that glorious afternoon, but not hard to believe how I ended up being an eyewitness to baseball history. Tom Seaver had been my baseball hero from the day he started his first game for the Mets in 1967, although I became aware of him during his one season pitching for the Jacksonville Suns in 1966. At that point, I was a 10 1/2-year old Mets fanatic desperate for a young star and baseball role model to cling to.

I attended my first Mets’ game at the Polo Grounds in 1963, watched the entire 10-hour epic double-header, including the 23-inning second game, against the Giants in 1964, and spent my early childhood thinking my favorite team would never get out of last place. By mid-1966, my burgeoning adolescent hormones were contributing to take my Mets obsession to a fever pitch. And like all Mets fans who didn’t think the losing was cute anymore, I was hoping for a savior to finally change our fortunes.

So I started checking The Sporting News, which in those days was considered the “Bible of Baseball” and printed every major league and Triple A box score from the proceeding week, in addition to all the league stats. I started noticing there was a 21-year-old named Tom Seaver on the Jacksonville pitching staff who was actually winning as many games as he lost.

Even more impressively, he was striking out an average of eight per game, wasn’t walking a lot of guys, and had a great hits-to-innings pitched ratio.

At that point, very few Mets fans knew about the bizarre circumstances that made Seaver a Met–the voiding of his contract with the Braves while he was still at USC, and the Mets subsequently being selected out of a hat in a lottery staged by Commissioner William Eckert. All I cared about was that we might finally be developing some semblance of a major league pitcher and I followed Seaver’s minor-league starts religiously throughout the summer.

Although it was clear that Seaver was the Mets’ best pitcher going into the 1967 season, he started Game 2 against the Pirates, struck out 8 in 5.1 innings and got a no-decision. By his next start, a 6-1 win over the Cubs, this hard-throwing righthander with the picture-perfect delivery was my favorite player and probably the favorite of every other Mets fan.

For me, Tom cemented his hero status on May 17, 1967. That year and until 1971, the Mets games on radio were carried on WJRZ-AM with a pre and postgame show hosted by an intelligent and very congenial man named Bob Brown, who staged various fan contests.

I sent in a bunch of postcards hoping to get selected for a call and before the game against the Braves that May night, my phone rang. It was Bob Brown offering me a chance to win a baseball glove if I could pick three Mets to get a total of four hits in the game at Fulton County Stadium. So naturally I picked the Mets’ three hottest hitters at that point–Tommy Davis, Ed Kranepool and Jerry Buchek.

Going into the ninth inning, Davis and Kranepool had combined for three hits (Buchek was shutout) but Davis came through for me with a single and I won a Bobby Shantz glove.

You may think this whole story has been a digression, but the kicker is this: Tom Seaver went three for three that night, with two RBI, a walk and a stolen base. The best athlete on the team was a rookie pitcher.

Anyway, you know what happened over the next couple of years. Seaver wins 16 games in both ’67 and ’68 (with 32 complete games combined) and then leads the Mets to the promised land in 1969 with 25 victories, including the near-perfect game against the Cubs.

After celebrating my team’s improbable World Championship, which I watched from my home in the South Bronx not far from Yankee Stadium, my family moved that December to the spanking new Co-Op City middle class housing project in the Northeast Bronx. Now 14, I was old enough to get a job delivering the Daily News in my 33-story building and the gig earned me about $30 to $40 a week, a fortune for a kid that age at that time. My plan for spending my new-found wealth? Go to as many games of the defending champs as possible, especially considering you could sit in the upper deck behind home plate for a buck and a half.

But I didn’t want to attend just any games. I wanted to see EVERY game Tom Seaver pitched at Shea Stadium (that wasn’t on a school night, of course) and the Mets’ five-man rotation made it pretty easy to figure out when Tom Terrific was going to be on the hill. Seaver was on a five-day cycle even when there were off days. So I knew that after opening day on April 7, Tom would pitch on the 12th, 17th and 22nd, the latter a Wednesday afternoon game I could attend because it would be the second day of Passover and public schools would be closed. I really splurged for that one and for six bucks got tickets for me and my brother in the first row of the loge (second deck) behind home plate.

After settling into our seats on a beautiful spring day (I don’t recall it being chilly), Tom proceeded to strike out two in the first inning. The way the sound of the Seaver fastball was reverberating after hitting Jerry Grote‘s mitt only confirmed it was going to a long day for the Padres.

,Ken Boswell‘s double off some guy named Mike Corkins drove in Bud Harrelson (who had singled), giving the Mets a first-inning lead. But the Pods’ cleanup hitter and leftfielder Al Ferrara led off the second inning with a home run to tie it (I think it scraped the back of the fence on the way down) until we got the lead back in the third on a Bud Harrelson triple that just missed going out.

Given the Mets’ offense, which could disappear for innings or days at a time, I figured that run would have to hold up if Tom was to get a W. (I can’t tell you how many times during Seaver’s Mets career I sweated out a game because of lack of run support. My mother once threatened to start giving me sedatives whenever Tom pitched because I’d pace around the TV room and scream at the set imploring the Mets to score a freaking run.)

By the top of the 6th inning, Tom had yielded just one other hit and had nine strikeouts. Of course the score was still 2-1 so the ace would really have to bear down. After a popup and a fly out, Tom struck out Ferrara for his 10th K of the game.

I don’t think I was aware of it at the time–and I could be corrected if I’m wrong–but by the top of the 7th, afternoon shadows were starting to creep over home plate while the sun was still shining over the rest of Shea. This would not be good for a Padres lineup that was already flailing at Seaver’s fastball, which that day looked and sounded like it was in the upper 90s–and we didn’t need a radar gun to tell us that.

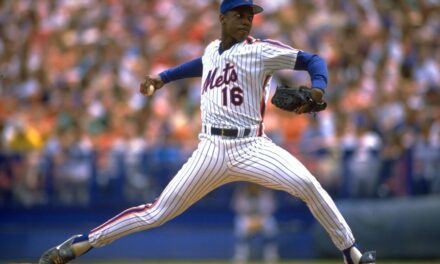

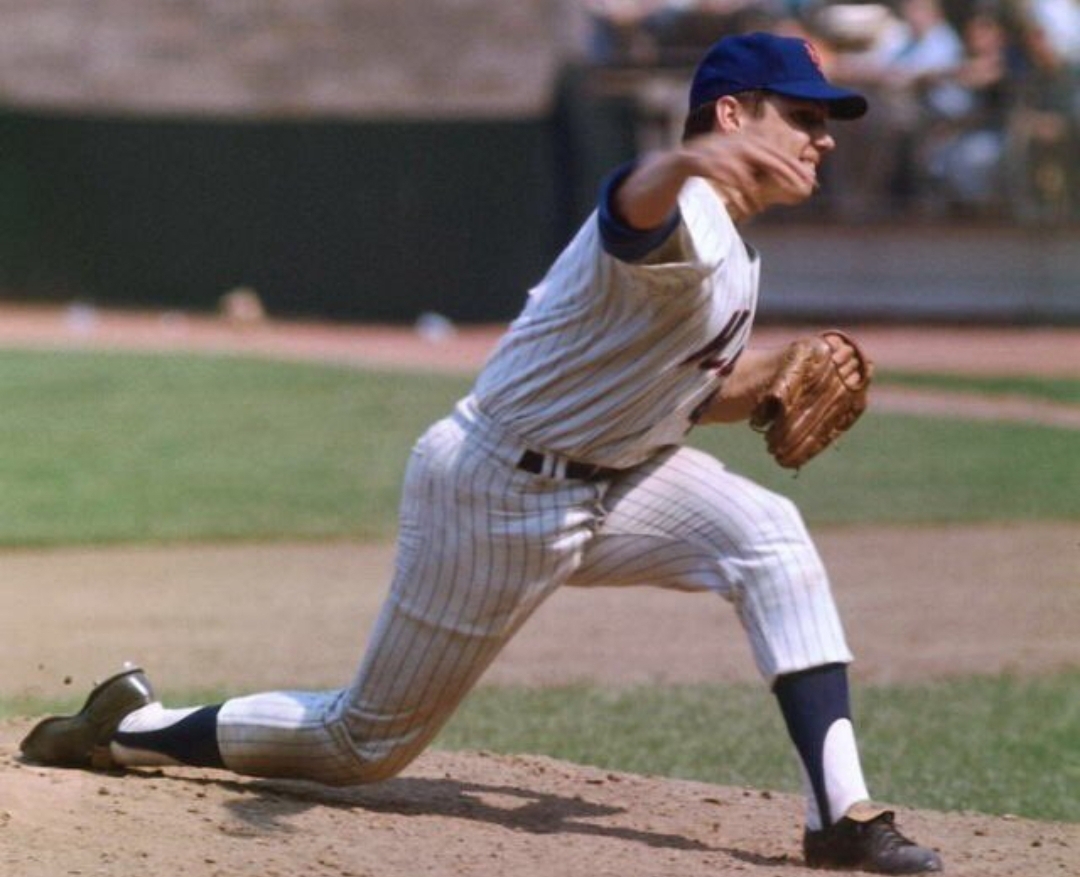

At this point in the game, I was totally transfixed on the man on the hill, picking up every nuance of that motion on the mound. As a Babe Ruth League pitcher, I was already mimicking Seaver’s delivery, which was never better described than by Roger Angell in The New Yorker after Tom was traded on June 15, 1977 (still one of the worst days of my life):

“One of the images I have before me now is that of Tom Seaver pitching; the motionless assessing pause on the hill while the signal is delivered, the easy, rocking shift of weight onto the back leg, the upraised arms, and then the left shoulder coming forward as the whole body drives forward and drops suddenly downward–down so low that the right knee scrapes the sloping dirt of the mound–in an immense thrusting stride, and the right arm coming over blurrily and still flailing, even as the ball, the famous fastball, flashes across the pate, chest-high on the batter and already past his low, late swing.”

In the top of the 7th, Seaver struck out Nate Colbert, Dave Campbell and Jerry Morales, the latter two looking. While that was impressive, none of the 14,000 of us cheering madly at every strike thought it out of the ordinary for our Tom and when he led off the bottom of the 7th, he got the obligatory polite ovation.

Of course if this game had been played in 2010 instead of 1970, Gary Matthews, Jr. would have been pinch-hitting because, hey, you need to get another run and our ace might be hitting his pitch count to boot. Thankfully, Gil Hodges wouldn’t think of pulling his best arm and when Bob Barton, and pinch hitters Ramon Webster and Ivan Murrell all K’d in the 8th (the latter two swinging), there wasn’t a soul in Shea who thought we weren’t watching history, let alone believe the Padres would actually hit another pitch.

As Tom took the mound for the top of the 9th, the buzz in the park was palpable and my heart was palpitating. Van Kelly led off the ninth and when he struck out swinging for the 8th strikeout in a row, the crowd sounded more like 40,000.

With every strike that whizzed by a Padre hitter I felt as if I was being levitated out of my seat. I don’t have a pitch chart of the game (don’t know if there is one available), but it seemed as if every pitch in those last two innings were strikes and the crowd roared louder with every one. Cito Gaston struck out looking for nine in a row and 18 for the game. One more strikeout and Tom Seaver would set a new record of 10 Ks in a row and match Steve Carlton‘s 19-strikeout game (which he lost thanks to those two Ron Swoboda home runs) against us the year before.

With the entire park on it’s feet and screaming itself hoarse, Tom fittingly blew away Ferrara for the record-breaking K. By this point I was jumping up and down so wildly I almost fell over the loge railing. I carried that emotional high all the way to 7 train and for the entire trip back to the Bronx. It is still the greatest pitching performance I’ve ever seen live (and I saw a couple of Seaver one-hitters and his 300th win at Yankee Stadium). Again, the Terrific One didn’t just strike out 10 in a row, he mowed down the LAST 10 IN A ROW.

As you can see above, I dutifully saved my scorecard of that game (and I wasn’t a kid who kept score much, so I must have had a premonition) and all of my handwritten annotations (including the note about Jerry Grote setting a new putout record-20) were added that day. There is one additional scribbling on the Mets side of the scorecard.

In early 1983 I was about to launch my own magazine called NEW YORK SPORTS and the Mets gave me the best launch present I could imagine by bringing Seaver back from the Cincinnati Reds that winter. Putting my idol on the cover of my magazine’s premiere issue was a no-brainer and before spring training I hiked out to Shea with a camera crew to shoot Tom Terrific.

As I was leaving my house that morning, I thought, “Damn, I’ve got to ask Tom to sign the 19 K-game scorecard” and found it in a huge pile of Seaver memorabilia I had been collecting for years. After assuming my best professional editor’s air during the photo session (even pressuring my hero to smile once in a while), I reverted to sheepish fan mode and asked Tom to autograph the scorecard. As he turned my prized possession into even more of a collector’s item, he looked down at the card and said, “Hmmm, that was a pretty good outing.” Indeed.

There’s one more postscript. In 1996-97, I was editing a elementary school classroom newspaper and decided to do a feature on the Baseball Hall of Fame. The executives at the Hall took me to lunch at a quaint Cooperstown bistro and we spent a pleasant hour or so talking baseball history. Naturally, Tom Seaver came up in the conversation and I told my story of attending the 1970 pitching masterpiece, mentioning that I still had the scorecard. The Hall curator perked up. “Wow, would you be willing to donate that to the Hall of Fame?” he asked wide-eyed. “Well, what would I get for it,” I responded. “Well, we could give you a lifetime pass to the Hall of Fame.”

I’ve been to the Baseball Hall of Fame a few times since that lunch meeting. The scorecard still resides in my own personal Tom Seaver Museum. Happy Anniversary, Tom!