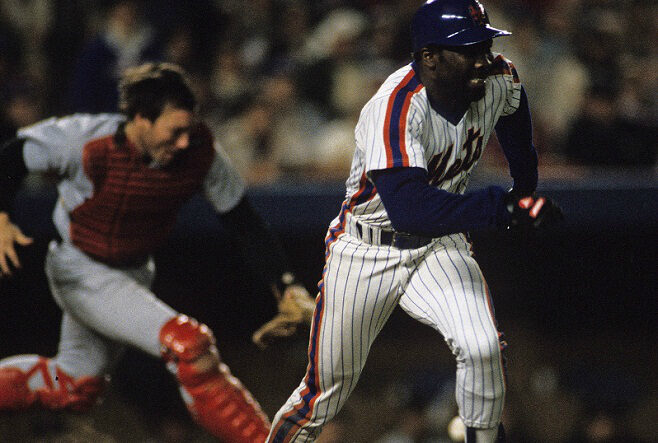

The 1986 Mets weren’t just an all-time team. They were a representation of the city in which they played — loaded with compelling characters who collectively formed a rollicking, raucous group that brought home a World Series title.

For Nick Davis, it was an epic story that needed to be told. He did so in a four-part documentary which premiered on ESPN this week.

A lifelong Mets fan with a first-hand account of that memorable ’86 season, Davis provides background on project’s origin, challenges he faced during the process, and what he hopes viewers can take away from the film.

****

BW: Now that we’re a couple of days into the film being released to the public, how has the reception been thus far?

ND: The reception has been great. It’s kind of everything you hope for. People really seem to like it and get it and understand what we were going for. And I think for some people, for a lot of fans of a certain age or older, it’s taking them back to a time and place that they are really enjoying going back to. And for those younger, it’s taking them to that same time and place and they’re interested and entertained by what they see.

BW: There are those who might say something to the effect of, “haven’t the ’86 Mets been overdone?” What was your approach when taking on this project and this subject matter?

ND: There are all kinds of things that haven’t been reported before. But more importantly, telling the story in this form has not been done before. Nobody had done a long-form documentary about the time and the team and the place. So the advantage of the form is to take you back and be able to give you new emotions and feelings.

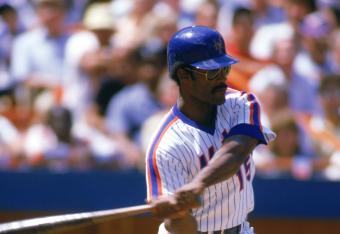

That’s what television film documentaries can do. Here’s a fact that you may not have known before, but here’s a feeling, and here’s a character you didn’t get to know before. We now feel and see Dwight Gooden in a way that I don’t think we’ve seen and felt before. I don’t think people know what Keith Hernandez was dealing with in terms of his father.

A film can make you feel in a different way than a magazine piece can. Then on top of that, you’ve got him sitting there with his cat. And so this gives you a new feeling that yes, I’ve seen this game before. There’s nothing new here, but you haven’t seen Keith describe his at-bat against Bruce Hurst in the 6th inning of Game 7 with Hadji right there. He’s never addressed the cat in the film until the moment when he talks about the base hit. That’s a cinematic gift that we were given.

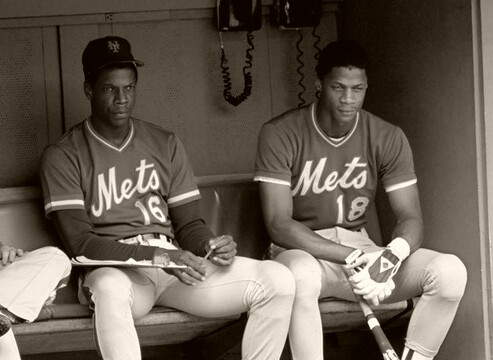

BW: With the depictions of Gooden and Darryl Strawberry, separate narratives as far as their upbringing and downfall are concerned, society has now better acknowledged the struggles people try to overcome when it comes to addiction. So with nuance and understanding, their stories are told much differently.

ND: Yes. Very much so. I think most of society tends to look at drug addiction as a disease now. And it was not seen as widely that way back then was a moral failing. We definitely are looking at those guys’ stories in different ways now, probably more sympathetically. I also think that they are opening up about their struggles in a way that I think they’re less defensive about it than they’ve ever been.

They’re definitely two different guys. When Strawberry came up to the majors, we knew he came from a broken home. We all knew that his father had walked out, and we didn’t know the extent. We didn’t know the violence. We knew he was troubled, and we saw it on his face.

Gooden was a totally different story. He comes from a solid middle class background, and he’s angelic with the press. He comes out of the gate, storming out of the gate wins Rookie of the Year and then the Cy Young with this off-the-charts season. Even when whispers were going around, when it was revealed he failed a drug test and had to go into rehab, it caught you totally by surprise. So the fact that, as he reveals in the documentary, he came from such trauma. There was a lot of violence that he witnessed. It’s completely revealing and makes you understand. Just knowing this guy comes from a solid middle class background, we don’t have to worry about this guy. That’s not true.

BW: A general perception is that the ’86 Mets are glorified and their reckless and raucous behavior is either glossed over or not held in contempt. How did you go about telling the whole story regarding off-field behavior?

ND: It was never my intention to glorify them. It was my intention to tell the story cinematically and move audiences, thrill them and have them get caught up in the fun and also get caught up in the sadness and get caught up in the darkness. The one thing that no one’s pointed out is that we were complicit. The theme song that we chose was Tom Waits’ “Clap Hands.” It’s very dark song. The first line is: Sane, sane. We’re all insane. We’re applauding them, we’re caught up in the badness. So it’s actually a fairly dark perspective on the story. We talk about how there’s a lot of things that were being swept under the rug.

I’m not trying to condemn anybody. I’m not trying to judge anybody. But I hope that emotionally, people go on a journey that takes you back to this time and you feel the emotions and you ride this rollercoaster with these guys. It’s a pretty dark tale that we told; it’s not perfect. I think that it’s cautionary.

BW: Was there a reluctance amongst players or anyone associated with the team to delve into everything that was involved in this story or has the passage of time and the general understanding of what went on allowed them to open up?

ND: It was a little of both. I think everybody has a slightly different feeling. And I think some of the guys who we did end up interviewing were sort of like, “not this again” and “you’re just dragging up all the bad stuff.” And then when we got into the interviews, and they saw that we were trying to tell the complete story, that’s when they started to really open up. Also, a lot of these guys are at points in their lives where they’re happy to talk about this thing that was really meaningful to them 35 years ago and get into how they felt and things they have learned since.

BW: Was there a challenge in getting cooperation from Major League Baseball and the Mets?

ND: Yes, there was. And I have to give full credit to Nick Trotta at MLB because the way this came about is because of my previous film on Ted Williams for PBS and I worked with him on that.

So based on his experience with me in the previous film, he felt I could be trusted with this subject matter. This is not an exposé, but we’re not going to whitewash it. We’re going to tell the complete story. And I think the Mets felt it was fine too. Thirty-five years later, it was fine to have this story be told in full.

[Former PR Director] Jay Horwitz is another guy I have to thank. Jay is such a legend and such a wonderful guy. When Jay tells them, “hey, you should do this,” they come on board. Not all of them. Some of them said no. But it really was a long, complicated process.

BW: What was the most challenging topic to depict — either from a production standpoint or the weight of the subject?

ND: The two trickiest were women and race. We did a lot of work on it. I’m not saying we came out of the right way, but we had a lot of material. In terms of women, balancing it out without being judgmental or applying our current standards to the standards of 1986. But at the same time, we don’t want to just be like, well, boys will be boys.

So finding that balance where you’re depicting it. You’re depicting the fun they were having, but also the not great attitude they were sort of inhabiting. That was tricky.

Talking about the race issue was equally complicated and challenging. And the way George Foster left that team after four and a half years was a really important issue. When we handed in our first rough cut, it totaled 6 hours and 25 minutes. We had to get down to 3 hours and 21 minutes. The suggestion from certain executives was to just drop the Foster issue. There are certain things you just don’t have time for and reasonable people can disagree. I can imagine another filmmaker would do it differently since he’s not part of the World Series team. But in the interest of just telling the story as actually happened, that was not something I ever entertained.

BW: Was there something you, in fact, had to cut from the final version that you wish you could have included if you had more time?

ND: Well, there’s a lot of little things. There’s little baseball things that I wish we’d had time for. The fact is, Ron Darling pitched the game of his life against the Cardinals in October 1985 with nine shutout innings. I wish I’d been able to include that.

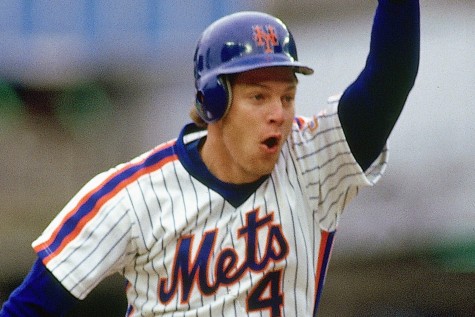

I wish, frankly, I’d been able to get into the rain out (in Game 7 of the World Series) and how it affected the rotation on the Red Sox. And then just some terrific off-the-field stories that we just didn’t have time for. There is one that I really do regret that we couldn’t get in because it demonstrated, I think, Ray Knight’s importance to the team — stopping a fight on the bus between Strawberry and Gary Carter. But his leadership was depicted in other ways.

BW: How significantly did the pandemic affect the making of the film?

ND: It really scrambled our production plan. And look, this was a dream to work on. While the world is essentially in a war, it was amazing to have something you love that you were working on every day. But it was difficult. Typically, in a documentary like this, you would film all your interviews and then start editing, and we didn’t have that luxury.

We had to start editing well before we were finished with interviews. We had so many of them and an almost six-and-a-half hour rough cut, but we hadn’t gotten to interviewing the beat reporters. I wanted to interview at least one who covered the Mets. But also we still hadn’t gotten Darling and (Roger) McDowell, and we were running out of money. And you can only interview one person a day during COVID. I did wish we had included some of the beat writers or somebody who actually covered the team at the time, but I don’t miss it when I watched the film.

BW: Lenny Dykstra is, to no surprise, outrageous and intriguing. What was that interview like?

ND: That was one of the most amazing experiences I’ve ever had. I was in my office conducting it with him over Zoom. It lasted about four hours and he was incredible. He was very available. He was incredibly open. He’s off the wall, but I actually think that he’s crazy like a fox.

I think there’s something kind of brilliant about him. He was obviously a baseball savant. So when you’re speaking to somebody like that, you see the intelligence at work, even if he seems a little inarticulate. After the life he’s had, you can certainly say what you will about it. But it was an incredible experience. The first five or seven minutes were the funniest things I had ever heard.

He was so profane. Some of what he said was completely unusable and unprintable, but so funny. I had to mute my microphone at times because I was laughing. And yet by the end of the interview, he’s really opened up about what it meant to him to be part of that team and to win a World Series in New York City and be feted at Peter Lugers Steakhouse after hitting the home run in Game 3 (of the NLCS) against Houston. Taking him back in time and reliving those experiences with him was great for him.

BW: In the open of Part 4, fans (through submitted videos) give their “where were you” story about Game 6 of the World Series. What’s yours?

ND: As a Met fan, I make it a rule not to adjust my life for them because there have been too many times when I have canceled plans and then done something so that I could watch a game and then it ended up that they lose. I had auditioned for a play in college and I got the part playing an anchor man in a production of “The Skin of Our Teeth.”

I brought my roommate’s small Sony Watchman onto the set and sat there, off to the side, during the entire play. I didn’t have very many lines. Every once in a while, they would bring the light up on me and I would say whatever my lines were. But I was watching the game while on stage and I covered the watchman with something. Unfortunately, as the play was ending I was part of some dancing or whatever.

So I missed part of the 10th inning but got back to the Watchman when it was 5-4 and I watched with a crowd of other Mets fans surrounding me during Mookie’s at-bat.

You can stream the four part documentary on ESPN+ and follow Nick on Twitter @NickDavisProds.