Rick Peterson has grown up knowing baseball his entire life.

His dad, Harding William Peterson, played professionally as a catcher with the Pittsburgh Pirates in a limited role in the mid-to-late ’50s, appearing in a total of 66 games. With his playing career behind him, Peterson later adapted to life in the front office. He was the Pirates’ Scouting Director from 1969-76, then co-General Manager from 1977-78 to GM from 1979-85.

Rick followed in his dad’s footsteps, getting drafted by the Pirates in the 21st-round of the 1976 MLB Draft as a pitcher. The left-hander would never reach the majors though, as injuries derailed his professional career.

Despite not making it as a player, Peterson found another outlet in baseball.

He took his knowledge of pitching, along with his degree in psychology, to more than three decades worth of coaching throughout multiple organizations in baseball.

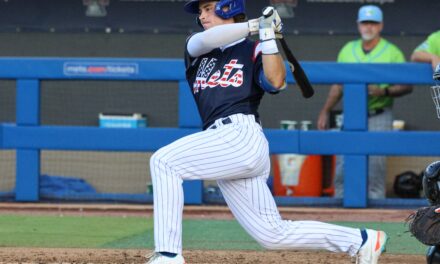

From his time in Oakland during the Moneyball era to his tenure in Flushing with the Mets, along with stops in Milwaukee and Baltimore, Peterson has tutored and mentored a plethora of All-Star and Hall of Fame pitchers during his lengthy career.

Peterson has recently started a new chapter in his life, appearing at corporate workshops and dabbling in public speaking engagements.

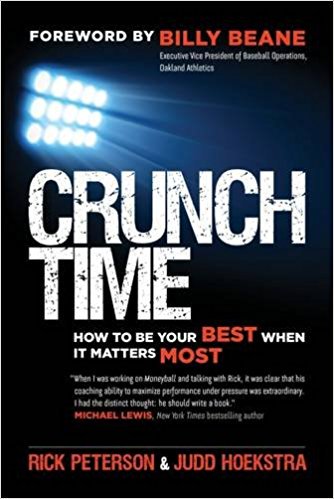

He co-authored the book Crunch Time: How to Be Your Best When It Matters Most, with Judd Hoekstra, a renowned leadership and human performance expert. The book details how to perform at your best, even in the most challenging of circumstances.

Peterson uses multiple examples from his coaching days to highlight the challenges that were faced, and the techniques and skills to overcome them. The book was released this past January.

I had the privilege of speaking with Peterson early last week, where we discussed his roots in professional baseball, working as pitching coach with the Moneyball A’s and the New York Mets, and his new book.

MMO: You worked your way through years of minor league coaching in various organizations after your playing career was through. What was the journey like from playing professionally, coaching at a young age, and finally, making it to the big leagues as a pitching coach?

Rick: I hurt my arm. I was seventeen and drafted out of high school by the Orioles. I had scholarships to go to play baseball at Harvard, Duke and Tulane. But back in the ’70s, major league teams did not want four-year college players, they wanted high school or junior college players. I gave up those four-year schools. Plus, if you went to a junior college you could be drafted multiple times. If you went to a four-year school you had to be 21 or your class had to graduate in order to be drafted again. If I wanted to play professionally, the path was really to go to junior college.

I ended up going to Gulf Coast Junior College in Panama City, Florida, where we were pre-ranked number one in the nation that year. Oddly enough, we finished second in the nation. If you remember Donnie Moore – which is a really sad story – Donnie Moore beat us 1-0 in the National Final game.

In the spring of my freshman year, we were something like 18 or 19-0; we were undefeated. We went to one of the big tournaments in Georgia and in that tournament, all the scouts were there. Everybody on our team, in my memory, almost everybody was drafted out of high school. I think most of our starting pitching was all drafted out of high school. We were all there just to go play professional baseball and get drafted.

I started one of the games in the tournament and I think back on it and I struck out 15, I walked seven and gave up six hits. I had to throw close to every bit of 200 pitches!

I talked to some scouts after the game and they were like, “Hey, you know we want to draft you but we don’t want to waste a draft pick if you’re not going to sign.” I didn’t even buy the books. [Laughs.] I told them, ‘That’s why I’m here!’

The next day we get into an extra-inning game and the coach comes down and said, “Rick, we really need you in the tenth or eleventh inning,” whatever it was. I went down to start warming up and I was like, Oh man, my arm feels terrible! But I got loose and came into the game and I got the first hitter out.

I threw the first pitch to the next hitter and grabbed my shoulder and walked off the mound; I was never the same. Back in that day they never even knew you had a rotator cuff. [Laughs.] You’d go get a doctor to look at your shoulder and they’d say, “Hey, your shoulder’s fine.” So I was able to pitch and come back.

I ended up graduating from Jacksonville University. I was drafted twice in junior college but because of my arm injury, nobody wanted to sign me knowing that my arm was bothering me. Then I was drafted out of college and signed with the Pirates. I pitched four years in the minor leagues and I hurt my arm the first season with the Pirates.

I never made it through a season healthy, so I knew my pitching days were over. I still had good enough stuff and being left-handed, I guess, if you felt like you were going to get healthy that was still a track to get back. It was after my first full year in pro ball, and every offseason you would try to figure out number one, where do I want to go spend the offseason? And number two, I’ve got to get a job someplace.

I decided to go out to San Diego. I took a trans meditation class when I was in college to help me perform better, along with my degree in psychology and art. I got into yoga and I was looking for alternative ways to stay healthy. I wasn’t getting answers from traditional people because, again, no one really worked out for baseball back in those days. I was just looking for ways of how I could stay healthy. It was nutrition, my mind, and through meditation and yoga, just trying to get myself into as top shape as I possibly could. I would always get myself close enough that I could stay healthy long enough, but I would always have some injuries.

When I was out in San Diego, ironically enough, I had about $1,000 to my name when I went out there, and unemployment was the highest in the country. There were no jobs. I eventually was forced to go apply for food stamps. Here I am on food stamps and I finally got a job as a teacher’s aide for like $60 a week.

I went to this free lecture, it was a holistic healer. He was a guy that was a chiropractor and also a kinesiologist and nutritionist. He was doing the lecture and he asked for a volunteer to come up, so I came up and volunteered and I was totally amazed at what this guy was talking about with the body.

Afterward, he said, “Look, I would love to work with you. I think I can really help you.”

I told him, ‘I’m all in. I have no money, but I paint. I’m an oil painter and I’ll trade off a couple of paintings if you’re interested.’

This guy worked on my body to get my body into total balance for about two months before spring training started. And in the midst of it, he suggested I go on a fast and he thought that would really be helpful. I did a seven-day fast and it was amazing where your mind goes after you’ve stopped eating, so to speak.

On the fifth day of the fast, I was walking on the beach in San Diego and the intention during the fast when I’d do these meditations was, what am I going to do with my life? I know I’m not going to pitch much longer. I was with the Pirates and they had interest. They said if I had interest in coaching, I might be a good prospect.

Back in the day, there weren’t young coaches. It was like, you played for a long time and then you got into coaching if that’s what you wanted to do. Murray Cook, who went on to be the GM of the Expos and also the Yankees, was really behind me, along with Branch Rickey III. They said, “You know, we’d think you’d make a good coach.”

I had no interest in coaching, my interest was in psychology.

But on the fifth day of the fast, it was like an epiphany on the beach. I really broke down and the message was very clear: You’re a teacher. It was this spiritual message. You’re a teacher. I’m like, All right, what am I teaching? And it’s like well, the only things you can teach are something you know, and the thing I knew most about was pitching and psychology, which are two pretty good blends.

After another year or two of being injured, we kind of had an agreement. Murray said, “If you get injured again this year, let’s think about coaching if you’re interested.”

In the middle of the year, I got injured again so I finished up the year coaching and said I’ll try this for a couple of years and see how I like it. I was still painting, I was traveling with my easels and canvases, and I was still doing a lot of mindfulness practice and a lot of yoga, and then I fell in love with coaching.

I decided at that time after a couple of years that this is what I was going to do, I’m going to be the best coach I could possibly become. I was doing research on the mental part of the game and how to improve to keep yourself focused, calm, and relaxed. I was intrigued with golf because golf was very similar to pitching and seeing how they trained.

I coached with the Pirates for several years and then the team was sold and I ended up going to Cleveland for three years. And then after three years there, they wanted me to stay, but I really didn’t think I had a future there.

I ended up with the White Sox and my whole career went in a totally different direction. In 1989, I go to spring training and I’m going to be the Double-A pitching coach with the White Sox.

Right before we left spring training, Larry Himes, the GM, calls me into his office. He said, “Rick, when you get to Birmingham, Dr. Andrews is opening up this ASMI lab solely for the study of biomechanics of the pitching delivery to reduce the risk of injury and to enhance performance. He just did Roger Clemens’ shoulder, and he’s just wondering if there’s some way we can prevent these injuries. You’re going to start taking our pitchers in there to get biomechanical analysis.”

I was the first uniformed coach – uniformed person – to ever walk in that lab when they opened. It wasn’t something I was interested in doing. I remember walking out of Larry Hines’ office and just going, Jesus Christ, what the hell did I get myself into? I said, ‘This isn’t baseball.’

Early on, we went back to the Bob Gibson era. We looked at Gibson, [Tom] Seaver, Nolan Ryan, [Don] Sutton and [Steve] Carlton asking is there something these pitchers do that maybe we can build a system around? And not knowing the answer.

As it turned out, there was.

We started getting analysis back and Dr. Fleisig would come back and say, “All right, Rick, his arm is late at foot contact. His bend of the knee is too firm at foot contact. It’s collapsing at ball release, and his hip rotations velocities are only 400 degrees per second.”

I said, ‘Really? What the f*** does that mean?’

He would explain to me exactly what it meant, and then I would say, ‘Okay, so what do we do with this?’

He goes, “I don’t know, I’m not a pitching coach.”

My mind was spinning, literally, trying to figure this out.

We did a ton of drills with the White Sox and I started to think, Okay, maybe from the same eastern philosophy perspective, wouldn’t it be nice to say you got your black belt in your pitching delivery, because you could literally master this movement and repeat it consistently? That was how my mind was looking at this. After we would bring a pitcher in to get his pitching analysis, then I’d have him do a drill, then we started testing the drills to find out what drills actually work.

Some drills worked really well and trained the delivery, and other drills didn’t work so good. Slowly we started piecing this puzzle together, and eventually, this evolved where it was a daily series of drills you could do consistently that you could keep the delivery intact, repeat the delivery, repeat the release point, which obviously once you can repeat it now you can locate more effectively which is going to allow you to be a better pitcher.

I ended up going to the big leagues as a bullpen coach with the White Sox several years later. During that time, I had met Dr. Charlie Maher who headed up the doctoral program at Rutgers University. They came to me and said, “Listen, we understand that you’re really into the mental game and sports psychology. We want to bring in some kind of program, we’re not sure what we want. We’re going to interview a few people, and we’d like you to put something together and interview for it.” I’m like, Wow, that’s interesting!

So through Charlie and myself, we put together a program and we did a presentation for Jerry Reinsdorf. I’ll never forget Jerry’s sitting there with his cigar and he’s listening to all of this and he read the material. Jerry would come to all the organizational meetings and he would take notes when you were evaluating players. He got the fact that okay, you’ve got this guy that’s topped out at Double-A or Triple-A and yes, let’s say he’s a pitcher. He’s got a plus fastball, plus changeup, plus curveball; but why isn’t he a good pitcher? Well obviously it’s his mind, it’s not his physical talent.

We asked for a three-year contract for humbling money. I’ll never forget Jerry. Jerry takes a puff of his cigar and goes, “Why would I pay this kind of money for three years on a program like this?”

I said, ‘You know, Jerry, we want this opportunity to do this because we think this is a difference-maker. We can help train the mental part of the game and bridge that gap with the physical potential and now train the mind, so this person could become a big leaguer.’

At that time the average salary in the big leagues was roughly just about a million dollars a year, and I said, ‘How about this: give us the opportunity to do the program, and we’ll do it for free. You don’t have to pay us. Put the money in an escrow account, and at the end of three years or maybe at the end of each year, we’ll take a look at it. And if no one makes it to the big leagues, and gets topped out at Double-A or Triple-A, then you keep the money. We work for free.’ I continued, ‘But let’s say two guys make it to the big leagues, that’s two million dollars, we’ll split it 50/50.’

He [Reinsdorf] took a puff of his cigar again and goes, “All right, let’s do the freaking contract.” [Laughs.]

MMO: You convinced him.

Rick: Well, if two guys made it and we walked away with $500K, he was offering us $40K a year to do this program, so he got it. And sure enough, I took 80 something players to this program, it’s called the Personal Leadership Program, and Charlie put together manuals and the whole deal.

That was revolutionary. We did that for five years and that’s the first time it was ever done in professional baseball.

We ended up getting fired in 1995, I went to Toronto as minor league coordinator in 1996 and 1997. Then I got fired in June or July of ’97, I ended up getting fired twice in two years, and mainly because we were trying to implement bio-mechanics and the mental game. When I got fired from Toronto they said, “Rick, baseball’s not ready for this. You’re way ahead of the game here. You need to maybe think about college, Major League Baseball is not ready for biomechanics.”

And then the Oakland A’s hired me to be the minor league director or pitching director. I came to instructional league, (Tim) Hudson was there that fall. Then I came to spring training that year and ironically enough J.P. Ricciardi– and this is my understanding of how this went – so Billy Beane said to J.P., “I want you to go down and I want you to see what this pitching program is all about.”

J.P. came down and I didn’t know that at the time. J.P. said, “Rick, would you mind if we just followed you around?” The Oakland A’s had not developed a major league pitcher who came from their system in something like 7-8-9 years, that was my understanding. They had players, [Jose] Canseco, [Mark] McGwire, etc., but they weren’t developing pitching. That was the reason they brought me in.

The day before we’re ready to break for spring training I get a call at 1:00 AM, and they said, “Hey listen, you need to call Billy. They fired the pitching coach and you’re the new pitching coach.” I’m like, What? All I had heard all spring was that everyone was on the ropes here. I said, ‘I don’t want to get up there. I’m hearing that Art Howe’s not in a good place, and I had just been fired twice in two years. And I like this place, and if I do this and it doesn’t work out I’m looking for another job again.’

I called Billy that night and Billy says, “Rick, I want you to take this leap. We’re going to put this program in at the big league level and I totally support this.”

I said, ‘Billy, I need a two-year contract to do this. I need two years guaranteed.’ He said he didn’t know if he could do that. And I said, ‘Well, let me just keep doing what I’m doing.’

At the time, I had two years on the pension plan because I was a bullpen coach for the Pirates as well for two years. And at the time you needed four years of pension time to actually get one. Then after four years every day just accumulated and at ten years you maxed out. I said, ‘I need two years guaranteed on the pension, Billy.’

We went back and forth, and he said, “Hey if we make a change …”

I said, ‘Okay, no problem. I’ll be the first base coach, I’ll be the clubhouse guy, I don’t care. I want two years on the pension.’ He finally agreed. I said, ‘Okay, I’ll be there tomorrow morning at six.’

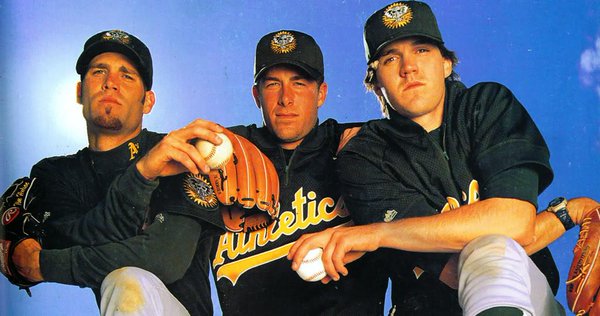

And before you know it, my whole big league career took off. Moneyball came a couple of years later and the scouting department signs Mark Mulder, Tim Hudson, and Barry Zito in three consecutive years.

MMO: You mentioned Moneyball and your start with the Oakland Athletics. Can you share some thoughts on your time in Oakland? How were you able to get so much out of the big three of Mulder, Zito and Hudson?

Rick: Well it wasn’t so much what I got out of them. It’s just like with Noah Syndergaard and I’m sure Matt Harvey and Jacob deGrom, they had a burning desire to be the best. They want to be the best.

We were going to take all three of them to the lab but Mark couldn’t make it for whatever reason. But we took Zito and Hudson to the lab two years in a row, so we were able to really design a customized program for them.

I remember sitting down with Zito and Timmy and saying, ‘All right, listen, here are the drills we do, here are the routines we do.’ Based on the analysis, I’d say, ‘Let’s add this to our routine. Let’s subtract this, let’s get a little bit more of this. Workout wise, let’s think about this from a conditioning standpoint.’ Our throwing program, or long distance, the whole deal, because now we had an MRI of the pitching delivery and mentally these kids were just off the charts. Mentally they were focused, determined, they had a high level of what I call competitive I.Q., that kind of competitive intelligence.

And here’s Zito. Zito came to the big leagues in July of his first full year in pro ball. He was the best pitcher in September in the big leagues. I want to say he was 6-0 (went 5-1). But he was the best pitcher in the big leagues in September, in a pennant race.

In his last start of the year, he was [up against] Clemens in Game 4, at Yankee Stadium. If we lost we’re done and if we win Game 4 we go back to Oakland for Game 5. I’ll never forget it because he was so anal; he used to wear a Timex watch when he warmed up, and he had his routine down to the minute.

And so playoffs, as you know, start at odd times. It’s like 8:17 p.m. because there’s all this stuff going on pregame. Zito comes in earlier and asked, “What time exactly is the game?”

I said, ‘It’s an 8:19 start.’ He’s looking at his watch and we’re sitting in the dugout and I could see him figuring this out. I start talking to him to try and relax him or thinking I’m relaxing him. As I’m talking to him he’s doing this panoramic view of Yankee Stadium, it’s empty at the time before the game. I’m asking him, ‘Did your parents get in okay? They got their tickets and everything?’

I realized after about a minute or so he wasn’t listening to what I’m saying.

Finally he looks at me and goes, “Rick, are you kidding me? Yankee Stadium, in the postseason, I’ve been waiting for this my whole life!”

I got all three of them together early on and I said, ‘You guys are really special and you guys are going to do some special things. You know what would be kind of cool? And you guys decide if you want to do it or not, but it would be kind of cool if you guys had a ritual that after you’ve warmed up for the game and walking into the dugout that you would take your warm-up ball with you and hand it to someone in the stands. That’s a moment they’ll remember for the rest of their lives, and it’s nothing for you guys.’ And they’re like, wow, that’s cool! So they started that routine.

So [Zito’s] long tossing in the left-field corner, and you know there’s no space there, there’s no foul territory. And this one fan’s leaning over and screaming at Zito. To the point where I’m saying, ‘Are you a professional ass**** or do you do this for free? Come on, man!’ The guy kind of backed off.

And so we’re warming up in the pen and they’re throwing coins at him and they get the security guy. And he [Zito] just looks at me and goes, “Rick, I love this, man. This is awesome!”

We’re walking in and we’re about 100 feet from the dugout and Zito’s looking in the stands because he’s looking to who he’s going to hand this ball to. I told him you’re not going to see any green and gold up here.

This one guy stuck out. He’s leaning over the railing going, “Zito, we’re going to kick your ass! You’ve got no chance!”

He’s yelling and pointing, and I look and he’s got two kids standing on each side of him. Zito locks in on this guy, he’s walking right towards him. Now he’s about ten feet away and the guy’s backing off a little bit because Zito’s looking right at him. I wanted to make sure I got close because I had an incident before where one of our pitchers got really close to the stands and someone spit on his face, and he had a knee-jerk reaction and just stiff-armed him. Thank God it didn’t get on camera. I mean, I never would of thought of it, I was standing right next to him and this guy spit right in his face, and he just reacted.

Zito bends over and hands the ball to one of the guy’s kids, and the kid looks up at his dad, and I’m just going wow, look at this! We start walking to the dugout and Zito goes, “Did you see the face on that kid? Man, that was so cool.” He was just so present.

He was sitting next to Matt Stairs while we’re hitting. Matty wasn’t playing that day. Olmedo Sáenz hits a two-run homer off of Clemens in the top of the first inning, and Matty is talking to Zito like a mile a minute, and I was ready to go, shut up, Matty! Just leave him alone!

The inning is over so Zito takes off his jacket, picks up his glove, and he turns towards Matty Stairs and like slaps him on the arm and goes, “Hey, this is going to be fun, Matty! This is awesome, man!” I’m literally looking at him going, ‘Who the f*** is this kid?’

I go to the other end of the dugout down where the bats are and I’m sitting next to Art, and Art’s looking at his lineup card and his hand’s a little shaking. And he goes, “Hey, how’s the kid today?”

And I’m like, ‘He’s better than you and I are today.’ And he beat Clemens.

The story about Hudson that sticks out in my mind was he had beat Randy Johnson earlier in the season in Arizona, like 2-1, a good game. This is the third week of August and we’re in Fenway Park. We’re two games behind, we’re in the race.

The day before, Peter Gammons came up to me and said, “I can’t wait to see Hudson tomorrow night against Pedro [Martinez]. There’s no place like Fenway Park when Pedro pitches. I’ve seen veteran pitchers literally get sucked out of the stadium.”

So I’m flipping a coin and I’m going, do I say something to Timmy? I don’t want to create more anxiety but at the same time I’m saying I want to prepare him for this, so it’s not such a shock.

So I go, ‘Timmy, you got a second?’ I told him I was talking to Peter and he said this wasn’t going to be like Arizona, because in Arizona, that place is like a mall, it’s like a shopping mall. This is not going to be like the mall you pitched at against Randy, I said, “Fenway is a lot different. There’s really no place like Fenway and when Pedro pitches.’ I continued, ‘You know what? You’re not really pitching against Pedro, because he’s not going to hit. You’re pitching against your lineup and just keep your focus on our game plan and execute like you have been all year.’

He’s looking at me and he goes, “Rick, me and Pedro Martinez in the pennant race? I’ve been waiting for this my whole life.”

I said, ‘All right. That’s awesome, man.’

We’re walking across the field when they take the field, and we’re behind the second base area, we haven’t got quite to the shortstop area and they took the field. And he literally kind of flinched a little bit and looked up to the stands, because it was so loud and unbelievable. I had known Nomar Garciaparra because I spent a couple of months with the Red Sox when I got fired from the White Sox, and he was in Trenton (Double-A for Red Sox, 1995-02) when I was there. So we’re right there and I look at Nomar and I said, ‘Are you playing again today? I thought you were asking for a day off or something?’ He said he’s been trying to get a day off but they haven’t given him one. And we both kind of smiled.

Pedro strikes out two in the first and you can’t even hear yourself think. Timmy goes out to the mound and he strikes out Nomar to end the inning. Timmy had this, you know how pitchers move kind of quirky? They just sometimes do quirky things. So he struck out Nomar and he used to have this habit of when he would walk off the mound he would look over his left shoulder. But he really wasn’t looking at anything.

As he’s walking off the mound he’s looking over his left shoulder and it appeared from Nomar that Timmy was staring him down, but he wasn’t. And then right when he turned back Nomar’s pointing at him and going, “F*** you’!” And the cameras picked up the sequence and they showed it on ESPN that night, but that really never happened. Nomar thought he was trying to show him up, and Timmy was just glancing over his shoulder.

Timmy gets into the dugout and the dugout at Fenway is so tiny, you’re on top of each other. He’s walking up and down the dugout going, “Come on guys, let’s go! Just get me a couple of runs, we’re going to kick this guy’s ass!” So I’m going, are you kidding me, man? It’s like his first full year in the big leagues!

Mark was very similar, I can’t really think of a specific story with Mark, but Mark was just incredibly confident and totally sure of himself. All three of these kids were just so special and they were so composed and if you take a look at their numbers, just like the Met pitchers.

What I’m really impressed with the Met pitchers is how well they pitched in the postseason. If you go back and look at a lot of veteran pitchers, take a look at [Tom] Glavine and [Greg] Maddux, you can look at a whole bunch of really good pitchers that did not pitch well their first couple of trips to the postseason.

MMO: Then you came to New York as the pitching coach for the Mets. From 2004-2006, you helped the pitchers place in the top-ten in team ERA, top-ten in quality starts, and top-ten in OPS against. What do you attribute that success to and were there certain philosophies you brought to the team during your tenure there?

Rick: I think we brought that philosophy [from Oakland], and I’ll backtrack. My first year in Oakland, the year before, Tony La Russa and Dave Duncan had left to go to the Cardinals, Duncan had this cabinet where he had all of his charts. He had blank charts in this cabinet that were organizational charts. I learned so much indirectly from Duncan because I saw his charts. And I’m going all right, I get it. If I fill this in and do the homework, here are the answers of how you lay out a game plan.

One of my first early habits to starting to lay out a game plan was really following in Dave’s footsteps, and then I ended up designing my own afterward, but that was the foundation. It’s kind of like, you see the foundation for it and it’s like all right, I want to see this, I want to add that.

When I first came to the Mets they didn’t really have an in-house analytics department. And because I was involved in so much of this over the years, I was a consultant for three technology companies, I was actually a senior adviser for Bloomberg Sports when they first got into their technology for baseball.

I met everyone in that industry during that time and everybody wanted to talk to me and because of Moneyball. In my first year with the Mets, they bought about 100 copies of Moneyball and passed it out throughout the organization. We’d get conference calls on Moneyball and book reports, that’s the impact it made on the industry. Because everyone wanted to find out what we were doing.

When I first came to the Mets they didn’t really have anything. We met with all of these people, all of these companies, and they said, “Rick, we’ll custom design anything you want.” We meet afterward with Jim Duquette, myself and Jeff [Wilpon], and a couple of other people. I said, ‘Look, they’ll customize it for us, but then they’re going to give it everybody else.’ There are no real patents on this. I said, ‘If you really want to do this the right way, buy the best database and then we’ll bring it in-house. If you want to bring in some smarty pants programmers, I’ll sit down with them and show them stuff that we did, and how to make it uniform-friendly. So as soon as you look at it if you’re in the dugout you’ll know exactly what all this means, and it’s very easy to digest.’

So that’s what we ended up doing. I think what happened was when you lay out a game plan you have every pitch in sequence and location and selection and the outcome of that pitch. Once you have the database, you go through every single hitter and it’ll be like, okay, he hits .188 on right-handed sliders down and away in this quadrant. He hits this batting average here. You have the data, and now it’s a GPS.

Once you can execute it you’re going to win, you’re going to do really well. If you can hit the glove, and I call our pitcher’s professional glove hitters, you get paid to hit the glove. If you hit the glove you do really good. And then you start to look at the fact that the batting average in the major leagues, this is every single year for probably 12, 13, 14 years or maybe more, if you touch the bottom of your kneecap that’s the bottom of the strike zone. From the bottom of your kneecap to below, the batting average in the big leagues is under .200 every year, that’s every pitcher.

If you take Syndergaard, my guess is Syndergaard’s batting average at the bottom of the strike zone might be .140. Johan Santana’s was probably .160. And when I came in we put a string up at home plate; this is the .190 line.

Then you look at the TrackMan data and, for example, one of the data points of TrackMan is where’s the ball 40 feet from home plate? And they use 40 feet because that’s what they’ll say when the batter has to make up his mind. Will I stop a swing or am I going to continue to swing? If you throw this pitch six to eight inches below the kneecap, that pitch is a strike at 40 feet if you’re in swing mode.

It was interesting, I was listening to a radio show a couple of years ago, and they had the analysts on talking about who in the last say 15 years had some of the top changeups in the game. Pedro, Glavine, Santana, [Trevor] Hoffman and [John] Franco. I’m going wow, I guess I must know what a pretty good changeup looks like! And then you ask them what their thought process was when they threw their changeup they all were the same. They wanted to throw their changeup over the plate underneath the strike zone for a ball. I mean, those are some of the best changeups in the game, and that’s what their thought process was.

When you look at it from that standpoint, you realize that you don’t have to have Syndergaard stuff. He’s got the best stuff as a starter in the game, you got that kind of stuff with that kind of mind, and our guys were able to do that during that time. We made it very clear, we laid out game plans and if you execute this you’re going to do really good.

MMO: During your time in New York, you got the chance to work with some All-Star and Hall of Fame pitchers, including Tom Glavine, Pedro Martinez, Johan Santana, Al Leiter and El Duque. Can you share some insight on a few of them, what their preparation was like before games, things you would go over with them, just the day-to-day operations that would go into making sure they were ready for a start?

Rick: I think it’s as much as anything else when guys get to the back end of their career, you just want to be much more conservative. Tommy never really liked to pitch on five days’ rest before he came to New York. But at that point in his career, it’s like Tommy, we need to do this and we need to find a better way.

The best way I can say this is that if you’re going to be a great teacher you have to be a great student. And what you’re a great student of you’re a great student of each individual pitcher you have. You want to learn as much as you can about them. What their physical vulnerabilities are, where their mental state is, all of their needs. And make sure that you’re taking care of all of their needs, I think that’s absolutely critical.

I saw El Duque this fall, and I hadn’t seen him since New York. And I hadn’t seen or even knew the story, I hadn’t seen that 30 for 30 ESPN story of him leaving Cuba. When I saw it, I got to tell you, Mathew, I was crying my eyes out. Not only because of the story, but because of knowing El Duque and I felt so terrible that I didn’t know that story about him while we were together.

I try to develop very close relationships with all of our guys and make sure that they know that their best interest is totally our motivation. Everybody deals with fear, worry and doubt, I don’t care how great you are. The greater the Hall of Famer, the more that they don’t want anyone to know their vulnerabilities. It becomes very personal. To be able to talk to them about these things is really critical because oftentimes they don’t have anyone to talk to about it. They’re not going to talk to a lot of teammates oftentimes, they will, but they’re not going to really express their vulnerability. I’m sure Glavine probably at a point when he was struggling was just like, man, will I ever get back on track here?

Same thing with Hoffman. I saw Trevor go through this in 2010 with Milwaukee. He blew his first three-five saves. And these weren’t groundballs going through the infield, these were homers way out of the ballpark. The struggles that he went through, the struggles that Al Leiter went through when he got injured, there was a point where he thought, well, that might be it. And he ended up coming back.

Having Johnny Franco at the tail end of his career. You’re talking about, I mean, everyone has a different opinion about closers, but in my opinion 400 plus saves is 400 plus saves. People who haven’t been in the dugout and vote don’t realize how great that is, the people that are there realize how great that is. But borderline Hall of Fame career without question.

When you see those guys at the back end of their career, they need as much coaching oftentimes as young players do in the beginning of their career because of the vulnerability. And then see how special they really are is really remarkable. El Duque and all the guys you mentioned, it was a privilege to say that I was a coach [for them].

MMO: You mentioned how several of the pitchers you worked with had to in a sense re-frame their careers when they get to the back end of it. I know that’s a topic in your new book that came out in January called, Crunch Time: How to Be Your Best When It Matters Most, that you co-wrote with Judd Hoekstra. Can you tell the readers a bit about your book and what can they expect from it? Also, how did you get involved in writing this book?

Rick: The seeds were planted for this book as a possibility when I was in Oakland during the Moneyball [era]. I sat next to Michael Lewis for six months. I learned so much from him and we would have these talks, a lot about solving pressure, the playoffs for these kids, and how these guys settle in. And he’s interested in the use of biomechanics to develop pitching.

Then in 2009, I was the technical director of Moneyball with Steven Soderbergh for five months. And spending five months with Steven Soderbergh, and he’s a baseball fanatic and he loves pitching, and he loves to talk pitching and knows it pretty well. He was always asking, “What do you say when you go to the mound in a really stressful situation, and you know they’re dealing with the stress and you’re trying to get their mind focused again?”

All those guys would always say you need to do a book. I said I would love to do a book, but I’m not doing a book about me and I’m not doing a book about baseball. If I could do a book and find a really good business writer, and write it from sports to business and business to sports, and then that whole thing just came together. It’s like the law of attraction, you keep getting attracted to that space and it all came together.

Then Judd and I met, and Judd had done a couple of books with Ken Blanchard, and Blanchard has written probably close to 100 bestsellers in the business leadership space.

We really collaborated on it and we brought the right people in to help guide us through. I learned so much about myself. Stories from Jim Abbott, back to the Chicago White Sox days, Glavine, Zito and Chad Bradford. And what’s nice is the stories are told through their voices, which is really nice because I didn’t want my voice involved with this really.

I wanted it to be about the concept and philosophy. That’s what you do as a pitching coach; you’re constantly re-framing pressure situations to shift it from a threat to an opportunity. Helping guys understand what these opportunities are on a daily basis and when you look at pressure of a baseball game, one pitch is the game. From the start of the game it’s potentially one pitch is the game, and then one or two pitches may blow out the game, but it was one or two pitches that got it to the blowout, it wasn’t fifteen or twenty.

That’s how the whole book came together.

MMO: What are your current thoughts on the Mets pitching staff this year? Obviously, many of them are coming off injuries, do you notice any red flags from the outside looking in?

Rick: At this time there doesn’t seem to be. I mean, they’re all hitting their assignments in spring training and it seems like their recovery is not only when they pitch but then you look at the next day or two and how they’re recovering. These guys are, I’m not trying to put any pressure on them, they’re at the beginning stages of All-Star [careers], and you don’t want to say Hall of Fame, but they should all be in the Cy Young conversation if they’re all healthy.

If they can get 30-32 starts apiece, because those kids in Oakland, they did it year after year. They were logging those 32 starts every year, so if they’re doing that they’re giving you 600 plus innings for three of them, but now you get four or five of them and they could give you somewhere like 900 plus [innings].

If your starters can give you somewhere close to that 900 range, now you’re taking a whole load off that bullpen. Not to mention the fact that when staff’s do really well, everybody pulls their weight and everybody does their share. If you’re running the household, someone’s got to clean the windows, somebody’s got to take out the garbage, somebody’s got to cut the grass. But what happens when someone can’t because of injury or because of lack of performance? Then it’s like, wow, I just did the windows, now I got to go cut the grass? I’ve got to take the garbage out? Then guys won’t perform well because they’re picking up more innings than what their role is so to speak.

You want everybody to stay in that space and that way as a manager, you’re able to put people in positions to be successful. You can pick and choose when they typically should be successful and not have to put them in situations where you’ve got to pick up this slack and this is not a place where you’ve typically been successful. And that’s how the whole foundation starts to crack.

I think the core of these guys right here is really special. They seem to be really special people because one of the things I’ve always said is the prerequisite to being an All-Star is you got to be an All-Star person. And it seems to me that these guys have the right work ethic. I mean, what Noah did this offseason to come in this kind of phenomenal shape, that’s a major commitment. There’s an incredibly high price to be the best, and that does not come cheaply.

These guys seem committed to do that and that’s really special.

MMO: Thank you again for your generous time, Rick. It was great to speak with you and look back on your incredible career in baseball.

Rick: My pleasure, Mathew. Be well.

You can follow Rick Peterson on Twitter @CoachRickPete.

Check out his website, RickPetersonCoaching.com