In the mid-eighties, Gregg Jefferies was on top of the world.

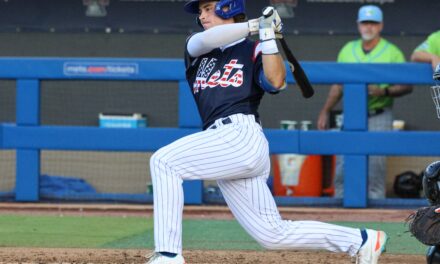

Selected in the first-round of the 1985 MLB Draft by the New York Mets (20th overall), he earned MVP honors in Rookie-level Appalachian (1985), Class A Carolina (1986) and Double-A Texas (1987) leagues, and was Baseball America’s first two-time Minor League Player of the Year (1986, 87).

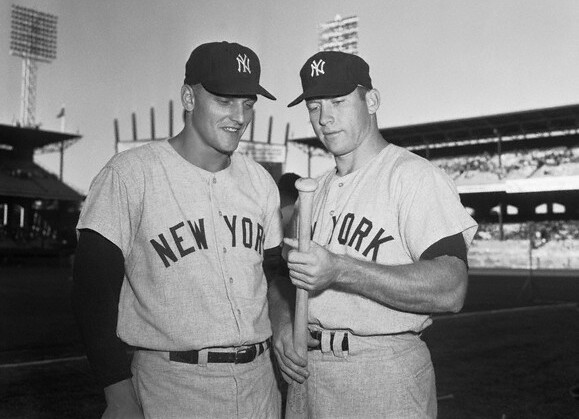

Drawing comparisons to Mickey Mantle – his dad’s favorite player – the 19-year-old California native was the talk of baseball. He made his major league debut on September 6, 1987, and finished his brief cup of coffee with the club collecting three hits in six at-bats (.500).

By the time Jefferies was recalled in August of 1988, he established himself as quite the minor league legend. Over 458 minor league games, Jefferies posted a .333 batting average, 47 home runs, 314 RBIs, 143 stolen bases, and 143 walks to 138 strikeouts.

The then 20-year-old continued to flash promise at the end of the ’88 season, posting a slash of .321/.364/.596, with 16 extra-base hits and 17 RBIs in 29 games. He proceeded to hit .333 in the ’88 NLCS against the Los Angeles Dodgers (9-for-27), tied with Darryl Strawberry for the most hits by a Met in the series. His .438 OBP in the NLCS was good for third-best among Mets with at least 10 plate appearances.

With high expectations placed on his young shoulders, Jefferies endured some turmoil and tough times on a veteran-laden team. Taking over for a clubhouse and fan favorite in Wally Backman, Jefferies experienced unrest from his own teammates, which created pressure to succeed early on in his young career.

When speaking to the 50-year-old Jefferies, he recognizes mistakes that were made and immaturity on his part, lamenting over what he could’ve done differently. Jefferies insists, however, that there were many stories and so-called controversies that were simply not true, with the media looking to stir the pot and create narratives that were just not there.

With a sense of unfinished business and the inability to live up to lofty expectations in New York, Jefferies uses the word “failed” when reminiscing about his Mets tenure. Asked if he felt any relief by being traded after the 1991 season to Kansas City, Jefferies replied, “You know, no. Not really. I felt like I let the Mets down. I know that’s a weird thing to say but I really felt like, yeah, I don’t blame you [for trading me].”

His best season occurred in 1993 with the St. Louis Cardinals, where he made his first All-Star team and posted career highs in home runs (16), hits (186), RBIs (83), stolen bases (46) and bWAR (5.1). He finished 11th in N.L. MVP voting that season, and cites moving to first base as a key reason he was able to relax and post his best season to date.

At the age of 32 in 2000, Jefferies completely severed his right hamstring, forcing him to retire from the game. It took him three years to even watch a game again, as resentment mounted over not being able to leave the game on his own terms.

Though his career was cut short to injury, Jefferies accomplished some terrific feats. From 1989 (rookie season) until his final year in 2000, Jefferies posted the fifth-lowest strikeout rate among qualified major league hitters at 5.7%.

And among players with at least 1,200 games played since 1908, Jefferies is one of only 11 to post:

- Less than 350 strikeouts

- Steal 175 or more bases

- Collect 1,500 or more hits

- Post an OBP of .340 or greater

Jefferies has found a second career as a hitting instructor in Anaheim, working at The Office Sports Academy for the last five years. His clientele includes major leaguers, college and high school athletes and kids as young as ten.

I had the privilege of speaking with Jefferies where we discussed how influential his father was in his development, the 1991 open letter read on WFAN about his frustrations, and how he looks back on his Met tenure.

MMO: Who were some of your favorite players growing up?

Jefferies: I loved Pete Rose, I loved the way he played. I loved George Brett. When I got to the minors, Don Mattingly was my guy. I loved everything about Don and the way he played.

In fact, I think it was 1987, he invited me to a Yankees game and he brought me down to the locker room. I sat and talked with him and it was just a thrill for me to meet a guy like that. If he didn’t get hurt he’d be a first-ballot Hall of Famer.

My dad and I would always watch him hit, and Donnie just did everything well. He was actually the guy that turned me on to Franklin fielding gloves. I used to use Franklin batting gloves and Donnie was using a Franklin fielding glove, and he said, “Gregg, you’ve got to use these.” When I moved to first base I definitely got myself a Franklin fielding glove because of Don.

The ultimate guy was Ron Cey. I was number ten in high school. When I was about seven, in school, I used to write Gregg ‘Cey’ Jefferies. The Dodgers were my favorite team growing up. In 1988, I’m taking ground balls at third base at Dodger Stadium, and I see this guy starting to walk towards me with a little guy. And I’m like, ‘What’s going on? Did I get released? Is someone going to tell me to get off the field?’

I look over and it’s Ron Cey. He goes, “Gregg, Gregg, come here.”

I said, ‘Mr. Cey, you were my favorite player growing up.’

He goes, “That’s what I heard. I just want to tell you that you’re my son’s favorite player.”

He had his little son with him and I shook his hand and signed an autograph. It was really kind of cool meeting my boyhood idol and me being his son’s favorite player.

MMO: Who introduced you to the game at a young age?

Jefferies: It was my dad. My brother and I played all the sports and my dad was a terrific athlete. We were just around it. It was just something that we did as a family. We played all the sports and my parents were pretty athletic and it just kind of manifested from there.

MMO: I read that you learned to perfect your swing from both sides of the plate by swinging a sawed-off bat beneath water while standing in a swimming pool, something your father had taught you. Can you talk about some of these drills and how they helped you develop early on?

Jefferies: My dad was the innovator of drills. I would come home from school and he would have a new drill for my brother and I. There was one day I came home, and I see tennis shoes and a sawed-off bat down by our pool. I’m like, Oh gosh, now what?

I go, ‘Dad, what do you have working here? What are we doing?’

He goes, “Get those shoes on, boy. And get that bat in the pool.”

He got the idea from the San Francisco 49ers. The 49ers on occasion used to train in a swimming pool, for the resistance. My dad just thought, what would happen if I got into a pool and I swung the bat underwater? The resistance was crazy, I mean it was so hard to do!

I remember a few big league guys asked me about it and I think Kevin Mitchell told me he started doing it. That’s one of the most popular drills people know me from.

We used to have a pool stick and little tiny wiffle balls and we’d have to try and hit it. Nowadays, you have those really thin sticks, so he came up with some stuff that was pretty unique. My father always kept it interesting. Working out with him was never a chore, it was always fun.

A lot of people tried to make my dad out to be a slave driver and forced me and my brother. It was never like that. We had so much fun with my father because he knew us so well. He knew if I had a bad day at school or when I was in a great mood and work off of that.

He was just a great innovator when it comes to teaching and, in fact, he’s in the California Hall of Fame for coaching. He was a scout for the Cubs and they wanted him to be the big league hitting instructor a long, long time ago. He just said, “No, I just don’t want to work with big-league players.” He loved working with high school and college players because they were like sponges. He loved teaching.

MMO: The workouts your dad would have you do sound pretty unique. It must’ve kept things fresh and interesting with the various drills he would prepare for you and your brother.

Jefferies: He put us through good workouts. My dad always said, “Do not be a labor faker.” We grew up pretty close to Oakland and that area, and my dad said, “Look, Gregg, there’s some kid in Oakland outworking you right now.” I truly believed that there was some kid in Oakland outworking me.

I always use it with my training with my kids and players, ‘Look, there’s some kid in Florida, New York, Japan, Dominican, that is outworking you right now.’ I said, ‘Don’t ever live with regret.”

What I mean by that is, whether you make it or not, when you’re older and you look down at your kids don’t ever feel like, If I only would’ve worked harder when they ask you, “Daddy, how come you didn’t make it?” Or, “Daddy, why did you make it?”

You don’t want to have that pit in your stomach to where, if I only would’ve worked harder, and that’s the regret that I never wanted to live with.

MMO: Prior to the 1985 MLB Draft, did you have any idea that the Mets were looking to select you 20th overall?

Jefferies: I had no idea. Our high school team was so good, we were really focused on our high school team. Our team was number one in the nation my senior year and I was so engrossed in that. I had an idea that I might get drafted at some point.

I never, ever thought I was going to be a first-round pick. Especially with the college players coming out of that draft, there’s no way. I had colleges picked out and at 5-foot-10, 180 pounds I didn’t think I was going to be a first-round pick.

MMO: You were named Baseball America’s Minor League Player of the Year in 1986 and 1987, and had such large expectations as a young kid, with comparisons to Pete Rose and Mickey Mantle. Did any of that bother you at all, or lead to you putting too much pressure on yourself, especially at such a young age?

Jefferies: I was very young when I came up, I think I was nineteen. I was very immature at that time. I wouldn’t say cocky but I wore my emotions on my sleeve. My whole career I did that, and it’s something I had to work on. Did I make mistakes in New York? Absolutely. Did I enjoy New York? I loved it there.

Believe it or not, when I broke in, the way that sold the best papers was the worst stories. It was never as bad as it was made out to be, there were times that I would read things and go, ‘Wow, where did that happen?’

New York gave me a lot; it matured me and toughened me up. Did I make mistakes? Absolutely. I came out and said when they were doing this comparison with Mantle, ‘The only thing that Mickey and I have in common is we’re both switch hitters and we’re both male.’ That was it. I never came out and said I was the next Mickey Mantle, no way! That was my father’s favorite player and I got a chance to get to know Mick and there’s no way that I ever, ever thought [that].

Maybe I was trying to live up to that and I just was pressing so hard that I was living every pitch as life and death, and that’s not a way to play the game. Plus, I broke in with a very veteran group and I was the only young guy on the team really. It was a very veteran group, but I cherished my moments in New York, I really did. The people that I see nowadays, whether it’s on a cruise or when I go back to New York, the people are fabulous to me. There’s nothing like playing on the East Coast, there really isn’t.

MMO: Were the struggles and pressures along with some of the turmoil in the clubhouse what led you to write that open letter in 1991 that was read on WFAN?

Jefferies: To be honest with you, hand on a bible – and I’m obviously very religious – that was not my idea. I didn’t write that letter. That was not my idea and I’m not going to say whose idea that was. It wasn’t my parents or my father. It was something that I was like, Ugh, I don’t know if I want to do this.

Without going into too much detail, I didn’t write that. That’s not really my style and I wasn’t raised that way. I was the kind of guy that you’d fight for everything.

The people that created that thought it might help, they were just trying to help. I was never raised to cry, I was not a crier. But there were times after games I had to pull over because I had so many tears in my eyes from how bad I was playing and the frustration I felt. People might read this and say, “What a baby.” It was all new to me. I was a young kid trying to fit into a veteran group and you’ve got to remember I replaced, not by my choice, a team favorite in Wally Backman. They loved Wally. And then here comes this kid. Why do we need Gregg in here when we had a winning ingredient with Wally?

Wally was good to me, Wally was nice to me. I wasn’t writing the lineup out. I just wanted to play. You know the saying hindsight is 20/20? When you’re in the thick of frustration and you’re just trying to please everybody and trying to get back to the way you know you can play, it just seems to get worse and worse because all I’m doing is pressing. Even on a day off if I went to a movie or whatever, my play was constantly on my mind. That’s hard to get away from.

In regards to that letter, that was not orchestrated by me.

MMO: Was there any sense of relief for you when you were traded to Kansas City in December 1991?

Jefferies: You know, no. Not really. I felt like I let the Mets down. I know that’s a weird thing to say but I really felt like, Yeah, I don’t blame you [for trading me].

I had a couple of decent years there, but the one thing that was really cool was my first game back. I never heard this since or before, when they announced my name I was playing with the Cardinals and it was my first game back at Shea Stadium. The PA guy goes, “Batting third, and please let’s welcome back, Gregg Jefferies.” I was shocked by that, and I got a really good ovation.

That meant a lot to me, even now I’m getting chills a little bit thinking about that because I felt like I let the Mets down. I wanted to play so well for them, the guys, the team, the team that drafted me. I felt like I failed, and that’s a hard feeling.

MMO: You posted one of your finest seasons in 1993 with St. Louis. You posted career-high in hits (186), HR (16), RBIs (83), OBP (.408) & bWAR (5.1). For you, what about that season made everything come together so well?

Jefferies: It’s going to sound really strange but it was defense. When they moved me to first base I never had a problem catching the ball, never. But my arm was always somewhat wild, especially at third base. I had a strong arm but I just didn’t know where it was going. [Laughs.] My hands were pretty small and I would throw over with one seam and two seams and I would literally be worried about defense.

I went to St. Louis and Joe Torre goes, “Hey Gregg, would you care about playing first?”

I said, ‘Absolutely not!’

It was almost like, Man, I can help the team and just relax and play. I know that sounds strange but I came from Kansas City and I hit around .290, but I think I led the league in errors at third base. I had Wally Joyner at first, one of the greatest defensive first basemen. So that played a toll. All of a sudden I go to St. Louis and it was like, Hey, I don’t have to worry about throwing. I can catch the ball, hit, run, and just do whatever.

MMO: Did the pressure subside then after you were moved to first base?

Jefferies: I don’t know if it was pressure except self-induced pressure. I remember reading Bob Feller saying, “You guys don’t know what pressure is until you have to shoot down an aircraft in the war.” He was a gunner and he had to take care of his whole squad. That’s pressure!

People that are living paycheck to paycheck trying to take care of their families, that’s pressure. Not throwing a ball over from third base. I think once I learned that this is a game, get back to being a game, I think that’s when my career changed. I went from hitting .275-.280 to .320-340, whatever it was. I just couldn’t stay healthy, that was my big issue.

MMO: You mentioned your health, and at the age of 32 you retired from the game of baseball due to a hamstring injury. How difficult was it for you to walk away from the game? And how long did it take you to feel comfortable about stepping away?

Jefferies: I completely severed my hamstring and they couldn’t fix it. Funny story, I was extremely close to Phil Garner, my manager in Detroit. Phil and I became very, very close and when they [doctors] told me, “Gregg, at this condition we can’t fix it,” I went in and told Phil, and we both teared up. I couldn’t believe I was done at 32, I was loving Phil, loving the team.

That winter I get a phone call from Garner and I go, ‘Hey buddy, how are you doing?’

And he goes, “How are you doing?” I told him it was tough.

He then says, “I want you to be my bench coach.”

And I’m like, ‘What?!’

He goes, “Yeah, I want you to be my bench coach.” Which meant if Phil got fired I was the manager.

I said, ‘You know Phil, I cannot thank you enough, but I still can’t grasp the concept that I’m done at 32.’

It took me three years, Mathew, to literally watch baseball again. To this day, you know when you get that fresh-cut grass and you get that smell of that grass? I get that out here and I instantly go back to spring training. It’s hard, it’s hard for me. I get that hollow feeling a little bit because it was a career that was incomplete.

I wanted to play until I was forty. I would’ve loved to have played more championship games and playoffs, especially with the Wild Card. I didn’t play with the Wild Card. Who knows what could’ve happened in my career if I was able to play eight more years.

MMO: Without putting words into your mouth, it seems that the worst part of retiring young was the fact that you couldn’t do it on your own terms. In a sense, you were forced out.

Jefferies: You are one-hundred percent right. When you’re forced out of something it’s tough. I got a chance to talk to Dusty Baker, who I love, a while ago. We were just talking and he asks, “Gregg, what happened to you? Where did you go? You were one of the best switch hitters I’ve ever seen.”

I go, ‘Dusty, I have no hamstring!’

He goes, “That’s what I heard. I heard that you got hurt and they could not repair it. That’s just a shame.”

When you hear something like that, from a guy you respect so much, it does ease the pain a little bit. I was a decent player, I played hard, and unfortunately, injuries caught up to me. I wouldn’t have changed the way I played but it created a lot of injuries.

MMO: From 1989-2000 you had the fifth-lowest strikeout rate at 5.7 percent. Many fans remember you for your patience, ability to put the ball in play, and low strikeout total. What was your approach at the plate and what made you so successful at limiting strikeouts?

Jefferies: You know what’s so funny, that is a great question. Every time I speak at conferences that is always one of the questions they ask me: Gregg, why didn’t you strike out? And I say, ‘Okay, everybody get your paper and pen ready because it is extremely complicated why I didn’t strike out.’ And I say, ‘Here we go, get ready, I changed…nothing.’

They go, “Wait, what? You didn’t widen out? You didn’t choke up? You didn’t move closer?” Absolutely not.

The only thing I changed was, instead of me looking gap-to-gap, I looked line-to-line. And they’ll ask, “Why didn’t you change your swing?” I used a 34-inch bat. Mathew, let’s pretend that you’re batting, and you’re using a 34-inch bat. For years you’re working with that 34-inch bat, you are swinging and you’re getting your swing honed in. You’re having a great at-bat, I call time out, I take your 34-inch bat now I give you a 32-inch bat. All of a sudden the length is different, obviously, but the weight is different. Where you’re standing is going to be different, everything about what you’ve worked on your whole life to create this perfect swing is now different because of the element that you changed.

What about not striding? Again, you are changing something that you worked on your whole life. My father taught me, “Gregg, hitting is a street fight.” Meaning, when you get two strikes your at-bat is not over with, you still have one more strike, don’t ever give up and give in. What I tell my college players, pro players, my high school players, even my twelve-year-old, ‘You don’t get half a point for hitting a weak ground ball to shortstop with two strikes. So you might as well go down like it’s a fight.’ And I lived by that.

When you start changing elements in a swing before you know it you’re lost in your swing. All of a sudden I choke up, I widen out and move closer to the plate, all these elements are changing. The strike zone changes, the weight of my bat changes, the grip on my bat changes, my approach starts turning defensive instead of still being offensive. When we get two strikes we’re not done, we’re not done. So we’ve got to battle throughout.

I’m not the kind of player that says, ‘Back when we played we were better.’ These athletes now are phenomenal, they are so gifted it’s crazy. The one thing that’s driving me crazy is that strikeouts are okay now, it’s okay to strikeout. We took pride in hitting balls hard; it’s not okay with one out and men on second and third to strikeout. And then your next at-bat hit a solo home run, it’s not okay for that.

You’ve got to be that complete player. When I played there was not one home run hitter that wanted to be called a home run hitter. They wanted to be called a great hitter with home run power. There is a big difference. Don’t ever call Barry Bonds or Ken Griffey a home run hitter, because those guys were beautiful hitters. They hit .320-.330 but all of a sudden popped 40-50 home runs, they were gifted. They weren’t happy with hitting .270 and hitting 45 home runs but having 195 strikeouts, they weren’t happy with that. That’s one thing I don’t like about the game right now is strikeouts are okay.

Our goal as a hitter, and this new era of launch angle, I don’t think I’m smart enough to play nowadays. I would be lost. This theory of wanting to hit the ball in the air does not make sense. We want to obtain line drives, but they’re counting line drives as balls in the air. So what deciphers a ball in the air? Is it a line drive or is it a fly ball?

Every great hitter loves that line drive, loves that backspin line drive. Now that might carry out but, man, you get that ball in the gap and it’s a line drive, that is the best feeling. That’s what as a hitter you want to do. The biggest misconception is when a guy fouls a ball straight back, I used to hate doing that. Think about it: when I foul a ball straight back it looks cool, believe me it looks great. But think about it, you are barely skimming the ball; you almost missed the ball by a full ball! It wasn’t a good swing, it looks cool and it looks like you’re right on it but I hated it because I’m thinking, Holy cow, I almost missed that ball completely!

Not one time have I ever heard Bryce Harper or Mike Trout say, “I want to hit the ball in the air.” Those guys love line drives. Maybe they have and I haven’t seen it. Man, when those guys hit home runs, they just take off. They’re like Mike Piazza home runs, just crushed. As a great hitter, you’ve got to obtain line drives.

MMO: I know you teach hitting lessons at the Office Sports Academy in Anaheim. Can you talk a bit about that and the age range of your players?

Jefferies: I’ve turned down some pro jobs as a hitting instructor because I just don’t want to leave. I’ve got my older kids, and I’ve also got a nine and ten-year-old. I obviously would love to work with more big league guys, but I’m not willing to sacrifice leaving my wife and kids.

The best thing about Southern California is you see a lot of big-league guys that live here. I never want to relinquish who I work with out of respect for their hitting instructors, because I know a lot of the hitting instructors, but I’ve got a lot of big-league guys I work with. A lot of college guys, high school level; I’ve got some ten-year-olds but I try to keep it high school to college. I love working with those guys because they really grab the concept of what I’m trying to teach and it’s just fun.

My father taught me, “Gregg, you’re not a coach, you’re a teacher.” Even though it’s two different words that seem close together, they are so different in terms. Being a teacher you’ve really got to be there for a kid in every aspect, not just baseball. You’ve got to be that soundbox; these kids go through some tough times. I just don’t want to be that guy who says, ‘Who cares, let’s just worry about your swing.’

I never have been and I think that’s why I do generate some clientele because they know they’re going to have fun and learn. If they’re having some issues and they need a voice box other than their parents, they know they can talk to me.

MMO: Thanks for your time today, Gregg. It was great to reminisce about your career.

Jefferies: I really appreciate it. Thank you for taking the time to talk to me.

Follow Jefferies on Twitter, @Gregg_Jefferies

Visit The Office Sports Academy online, https://theofficesports.com/wordpress1/