In continued remembrance of Tom Seaver, here is an updated version of the chapter on him from my book “The New York Mets All-Time All-Stars,” released this February.

The argument for the greatest Met ever isn’t an argument at all.

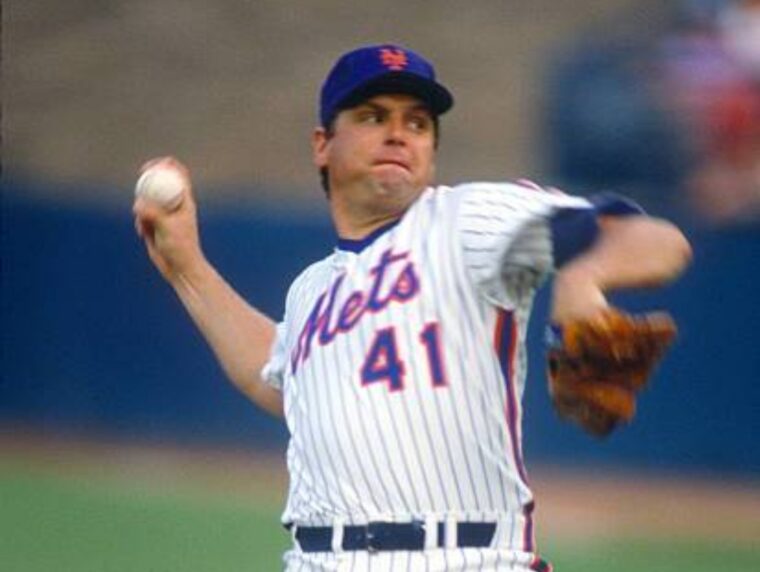

Seaver rewrote the Mets history book with his golden right arm, leaving an indelible mark on this team that will be almost impossible to erase. It would be less exhausting to recount the team pitching records he doesn’t hold. No. 41 is first in wins, strikeouts, complete games, shutouts, ERA, and All-Star

appearances.

But numbers and rankings don’t convey his full impact. Simply put, Seaver transformed the identity of an organization—doing so with an intense competitive drive and a scientific study of pitching. He examined the mechanics of his throwing motion, the art of keeping opposing hitters off-balance, and the understanding of each batter’s weakness. Never was Seaver going to be outsmarted or outworked.

Such diligence rubbed off on those around him. “When we started getting the feeling of competitiveness, it was all about learning how to win close games,” outfielder Art Shamsky said. “We were going to be lose every time he pitched, and Tom gave us confidence we could win those games.”

The Mets spent their initial five years with nary a sense of direction. And if not for an unusual sequence of events that ended with a favorable luck of the draw, he wouldn’t have been the one to provide it.

After multiple attempts for other teams to draft him fell through, Major League Baseball set up a special lottery for the former University of Southern California product under one condition: pony up at least $50,000. Three clubs had the payroll and the foresight to meet that threshold: the Phillies, Indians, and Mets. Three pieces of paper—representing the teams vying for Seaver’s services—went into a hat. You can figure out the rest.

This serendipitous match between New York and the right-hander from Fresno provided the backdrop to an unparalleled career. For more than a decade, Seaver and the Mets were synonymous.

The style and substance that defined Seaver’s baseball persona was readily apparent soon after his major-league career began at the start of the 1967 season. In a city where the media eats youngsters for lunch, Seaver demonstrated maturity that belied his age. “Even though he was a rookie, he was so far ahead of the hitters (mentally), it was unbelievable,” catcher Jerry Grote said.

During that time, first-year players were seen and seldom heard. Seaver quickly harnessed the attention of the public with 16 wins on a team that totaled only 61, posted an ERA of 2.76, and struck out 170. He was the lone Mets representative in that year’s All-Star Game and spoke to the press with the eloquence and assurance for which he was so noted.

Seaver’s Rookie of the Year performance laid the foundation for his upcoming brilliance. What followed would be a beautiful 11-season portrait. Seaver was the artist, the pitching mound his studio. His masterpieces are stored in the Mets historical vault like paintings in the Louvre. Two of his works stand out.

He asserted his usual dominance against the San Diego Padres on April 22, 1970, then took it to a new level. Beginning with the final out of the sixth inning, Seaver closed with a historical flourish. Nobody reached base. Nobody put the ball in play. When he fanned Al Ferrara to end the top of the ninth, he had struck out 19—tying a major-league record at the time. But his 10 consecutive strikeouts—to end the game, no less—is a record that has never been matched.

It was on this afternoon when Seaver received his 1969 Cy Young Award. And July 9 of the previous year was the best example of why he earned that honor.

In front of a jam-packed Shea Stadium, Seaver went through the first 25 Chicago Cubs batters unscathed. The electricity from the raucous sold-out crowd amplified as the string of outs accumulated.

Seaver calls it his best game, but also his “Imperfect Game.” Imperfect because of Jimmy Qualls—a man who had 11 big-league hits to date and who would end up with only 31 for his career. Qualls etched his name in Mets lore with a clean single to left-center—denying Seaver’s dream of perfection. Dreams of a World Series title, however, were soon to be realized.

It had seemed unimaginable prior to ’69. When the Mets surprisingly reached .500 in May, Tom made it clear he wasn’t in the mood for celebration. There was no reason to rejoice in such small victories, like they might have done before. Seaver was determined to help put the Mets’ days of despair behind them.

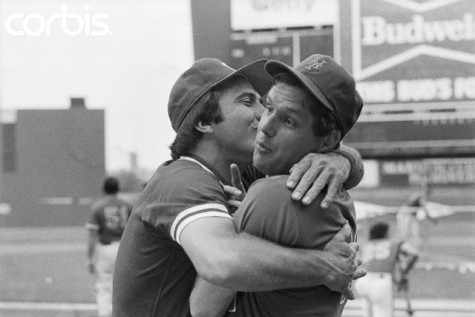

The Mets enjoyed numerous contributions throughout the course of their improbable journey—Tommie Agee patrolling center field with his magical glove, Donn Clendenon revitalizing the lineup after being traded to Queens in June, a rotation fortified by Jerry Koosman and Gary Gentry, and a bullpen headed by Tug McGraw and Ron Taylor. But Seaver was the star around which the rest of the team orbited.

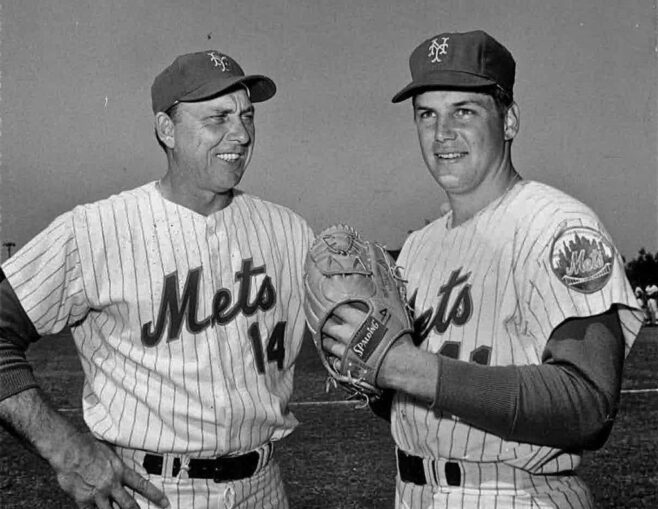

While he carried the fortunes of the Mets in his capable pitching arm, it was Gil Hodges who called the shots. Seaver—who, like Hodges, had served in the Marines—echoed the word of his manager’s straightforward gospel.

“Gil was a very dominant man,” Seaver said. “It was quite an experience playing for a man who was as strong in his feelings as Gil was, who believed in his feelings on baseball, his thoughts on baseball, and how baseball should be played.”

In 1968, the first year with Hodges at the Mets helm, Seaver showed steady improvement from his rookie campaign. He lowered his ERA to 2.20 and his WHIP to 0.978 while achieving the first of several 200-plus strikeout seasons. Both Hodges and pitching coach Rube Walker, the two biggest influences on the development of Seaver’s career, leaned heavily on education by way of repetition and correction.

“The biggest thing that they did was they gave you the ball,” Seaver said. “You learned by pitching. And then you try to dissect your mistakes . . . and as you go through the course of a career, then you intellectually begin to understand what you’re doing mentally and physically.”

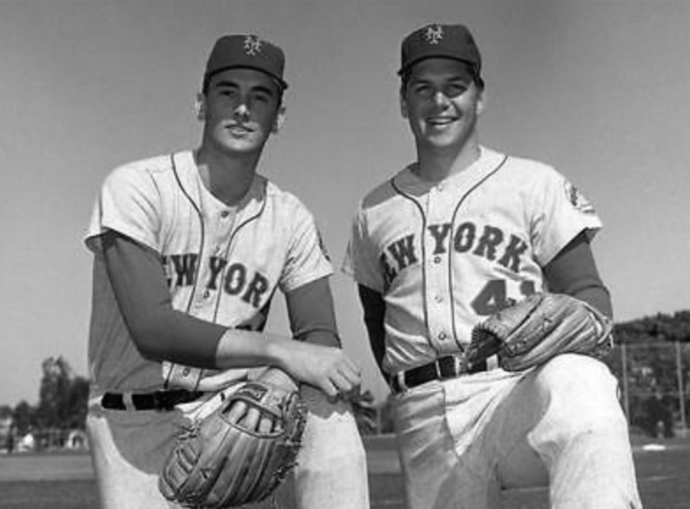

By the summer of 1969, the duo of Seaver and second-year left-hander Jerry Koosman had already acquired a wealth of knowledge. The next three months proved Seaver had attained mastery.

From August 9 through the end of the regular season, he made 11 starts and went 10-0—eight of which were complete games. His ERA during this crucial stretch was a microscopic 1.34. On September 9, Seaver went the distance against Chicago as the Mets closed in on the Cubs in the NL East race. New York passed them for good the next night. The Mets stayed so hot, they even withstood two lackluster Seaver starts in the postseason—first in the opening game of the inaugural National League Championship Series in Atlanta (which turned into a win) and then in the World Series opener at Baltimore.

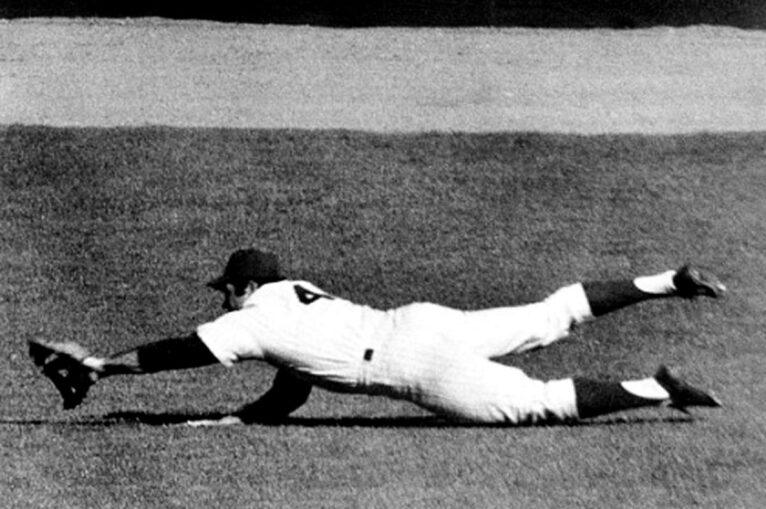

Seaver redeemed himself in Game 4 by limiting the vaunted Orioles offense to one run over 10 innings with the help of Ron Swoboda’s sprawling ninth-inning catch. One day later, the impossible dream came true in the form of a world championship.

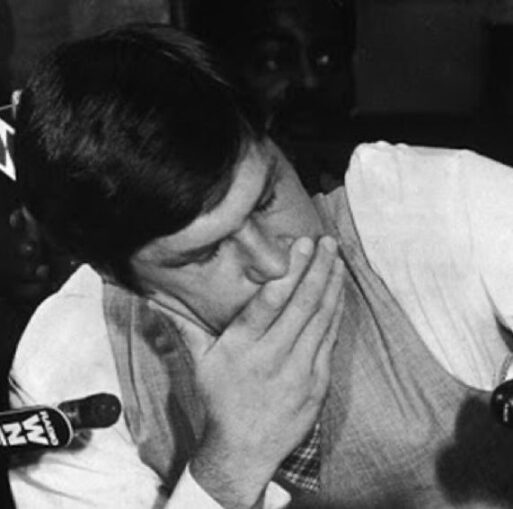

Not long after the ticker tape fell in lower Manhattan, individual adulations poured in. A 25-7 record and a 2.21 ERA were numbers worthy of a well-earned Cy Young Award and nearly the league MVP—falling short of the Giants’ Willie McCovey. Sports Illustrated later recognized him as its “Sportsman of the Year.” But beyond those distinctions came even more distinguished notoriety.

New York had unofficially inducted its newest sporting legend—fully embracing Seaver’s intelligence, integrity, and intensity in a city that thrives on such qualities. His legend only grew in the post-championship years—the three most overpowering seasons of his career.

From 1970–72, Seaver fanned an average of 274 batters, led the NL in strikeouts twice, and claimed a pair of ERA titles. Still, somehow, he never added to his Cy Young collection. The most galling omission came in 1971. Seaver constructed a career-low 1.76 ERA, a career-low 0.946 WHIP, a career-high 289 strikeouts, and a career-best 9.1 K’s per nine innings. Each of those figures were atop the league leaderboard at year’s end.

But the weight of wins tipped the scales in favor of Chicago’s Ferguson Jenkins, who tallied 24 victories to Seaver’s 20. There would be no snub in 1973, a season in which he kept the Mets afloat amid a deluge of injuries. Only twice did Seaver allow more than four runs in a start. And by mid-September, a replenished roster sparked a resurgence. Even as Seaver’s shoulder barked with soreness, the call of the pennant race didn’t go unanswered. Seaver locked up the division and the Cy Young in Chicago with the help of Tug McGraw to earn his 19th win and secure an MLB-best 2.08 ERA.

He then attempted to win the NLCS opener in Cincinnati on his own—responsible for the lone Mets run and keeping New York tied through eight innings. But he was done in by Johnny Bench’s walk-off homer. Seaver got another crack at the Reds in Game 5 with the World Series at stake. He wasn’t nearly as sharp (striking out four and walking five), but he didn’t need to be. Given a 7–2 lead, Seaver again passed the baton over to McGraw, who took the Mets across the finish line.

By pitching the NLCS finale, Seaver was available for only two World Series appearances. Both starts came with their own bit of frustration. He exited Game 3 tied after eight innings—a contest Oakland eventually won in 11. As the Mets took the next two at Shea, Seaver was set for a potential close-out start in the Bay Area. With the luxury of a series lead, manager Yogi Berra weighed his options. He could go with his best, Seaver, or his freshest, George Stone—12-3 during the regular season—and preserve Tom an extra day if Game 7 presented itself. Berra played his ace, sore shoulder be damned.

Seaver pitched well over seven innings, allowing two runs. His opponent, Catfish Hunter, pitched slightly better—one run over 7.1 innings. The result of that day and the next (both in Oakland’s favor) made Berra’s decision dubious, forever fostering debate as to whether the alternative would’ve yielded a different outcome.

Through seven seasons, Seaver had assembled a career worthy of mention among the all-time greats: an average of 19 wins and 236 strikeouts, a splendid 2.38 ERA, along with 121 complete games and 24 shutouts. So when he finished 1974 at 11-11 with a 3.20 ERA—a final stat line most pitchers would envy—it felt second-rate. Such were the standards for a pitcher of his caliber.

It indeed was an outlier from the expected brilliance. But, in fairness, his body didn’t cooperate. To say his year was a pain in the butt was not a figure of speech. A strained sciatic nerve on the left part of his backside forced multiple stints on the mend and severely curtailed hopes for a productive year.

Of sound body and mind, Seaver rebounded in 1975 back on-brand. During a season in which he went 22-9 and won his third Cy Young, he attained two significant strikeout milestones. First, reaching 2,000 for his career and, later, becoming the first pitcher to fan at least 200 in eight consecutive seasons.

Leave it to M. Donald Grant to ruin a great thing.

June 15, 1977, is a date that lives in Mets infamy. A date when the stubbornness of the team’s two most prominent figures reached its tipping point. A date that set the organization back for years to come. Owner Joan Payson’s passing in 1975 coupled with Gil Hodges’s death in 1972 erased Tom’s sources of comfort.

The bulk of the decision-making was in the less-than-capable hands of Grant. The team chairman expressed little to no interest during the advent of free agency and scoffed at Seaver’s demands for more money. To Grant, players of Seaver’s ilk were more arrogant than dignified. He was unwilling to understand the changing lifestyles of the modern athlete and publicly aired his grievances regarding his star pitcher’s wishes to be paid to the level of his immense value.

The sides did agree to a modest contract extension, but Tom was still disturbed by the paucity of Met free-agent signings. When a 2.59 ERA and a league-best 235 strikeouts could only equal a 14-11 record in 1976, it did little to curb his frustrations. Grant wasn’t alone in challenging the face of the Mets. He had a powerful voice taking up his argument. Dick Young, the legendary and cantankerous columnist for the New York Daily News, shared Grant’s disdain for free agency and regularly wrote with scorn for Seaver.

Tom went into 1977 disgruntled and continued to pitch with little support, but had secretly worked out a three-year extension with Lorinda de Roulet two days before the June 15 trade deadline.

But on that fateful day, Young dropped an atomic bomb. His latest column alleged that Tom’s wife, Nancy, was jealous of Nolan Ryan’s wife, Ruth, because his former teammate was earning a higher salary with the California Angels. Call it the match to the powder keg.

Seaver asked out of New York. The Mets bent to his demand, sending him to the Cincinnati Reds and letting the proverbial wrecking ball loose on what is now known as the “Midnight Massacre.” The cumulative WAR for the four players the Mets received over their careers in New York (12.3 combined) was only slightly above Seaver’s best season (11.0 in 1973). And it certainly couldn’t measure up to his stature. Naturally, the Mets took a nosedive into irrelevance.

Time passed, however, and Grant departed as the ultimate Mets villain. Queens now became a safe harbor for Seaver under the right conditions. They were in the winter of 1982, when the Reds dealt him back to New York.

At age 38, by baseball standards, he was an old Tom Seaver. But when he took the mound on Opening Day 1983 against Philadelphia—a glorious sun-drenched afternoon dripping with nostalgia—a packed Shea Stadium got to witness something resembling the Tom Seaver of old. He shut out the Phillies for six innings in a vintage performance. But before you could even conceive a full-circle finish to his career, the Mets somehow found another way to let Seaver go.

On the verge of his 300th win, Seaver was left unprotected in a free-agent compensation pool in January 1984. Much to the Mets’ surprise, the White Sox nabbed him. Soon after he called it quits on a two-decade career, the well-deserved post-retirement honors poured in. Some were appropriately swift—like the retirement of his No. 41 and the resounding, near-unanimous first-ballot induction into the Hall of Fame. Some came far too late—namely the statue outside Citi Field.

While his pitching days were behind him, he found a lifestyle where he could continue to hone his precision: running a vineyard. “Same thing as pitching—attention to detail,” he said in 2014. “You can’t force it. It’s a lot of fun.”

But even ordinary physical and mental abilities left him. It was revealed in 2019 that Seaver has dementia—stemming from the contraction of Lyme disease decades earlier—and thus was retiring from public life. It was a cruel diagnosis to someone renowned for his combination of strength and acumen.

That news and the announcement of his passing on Wednesday evening elicited memories from those of a certain generation who could vividly recall the countless outstanding performances, the signature drop-and- drive motion, and the incomparable influence he had on the fortunes of the Mets. It was a clear reminder that he is without equal in team history. Tom Seaver will be “The Franchise” as long as there is one.