Until the breaking news alert flashed on my cell phone in the early evening of Wednesday, September 2, 2020, I hadn’t cried over Tom Seaver for 43 years. That time was also on a Wednesday—June 15, 1977 to be exact—when the New York Mets inexplicably and unconscionably traded my ultimate idol and the best pitcher in baseball to the Cincinnati Reds. It was aptly called the “Midnight Massacre,” and it was a dagger through my 21-year-old heart. Perhaps at that age, I should have handled the news in a more mature fashion, but I wasn’t ashamed over being distraught and almost inconsolable for days. This was TOM SEAVER we were talking about—THE FRANCHISE—and frankly, I’m about to turn 65 and I still haven’t completely gotten over it.

While I shed many quiet tears watching the TV tributes and reading the newspaper retrospectives in the wake of Seaver’s passing, this tragic news was much less of a shock than the ’77 trade. I knew my hero had been diagnosed with Lyme Disease in 1991, a condition that reoccurred in 2012 and led to Tom suffering from Bell’s Palsy and memory loss. Then in March 2019, it was reported that Seaver was dealing with dementia, and when the Mets created “Tom Seaver Way” at CitiField last June 27, Tom’s daughters celebrated the day with the fans, but without their Dad.

During the last two weeks of this year’s pandemic-ravaged August, I noticed Tom’s daughter Anne posting more photos of her Dad than usual on Facebook and I had a premonition. On August 26, the Mets current “Franchise” pitcher Jacob deGrom was facing the Miami Marlins and, as usual, the SNY telecast was throwing up those numbers comparing deGrom to other iconic Mets pitchers. As I gazed at those Seaver stats that are burned into my brain, I turned to my wife and blurted out, “Honey, I don’t think Tom is gonna be around much longer.”

On the Monday, August 31 night that Tom Seaver died (reportedly from complications of Covid-19—his passing wasn’t announced until two days later), deGrom was again pitching against the Marlins. Five nights later, after beating the Philadelphia Phillies, the ace who this season could match Seaver with three Cy Young Awards, was asked about being compared to the iconic Tom Terrific.

“I really would have liked to have met him and talked to him some,” deGrom said, “But I think he’s the all-time great here [with the Mets]. You look at his numbers, the complete games [231], I don’t think I’m ever reaching that. It’s an honor to be compared to somebody like Tom Seaver.”

The day after deGrom pitched his typical gem against the Phillies, an adult fan who should know better posted this on Twitter: “Jacob deGrom is the best pitcher in baseball—maybe the best pitcher ever!”

As much as I adore Jake, I couldn’t let that stand and tweeted back, “Hey, calm down there, kemosabe. He isn’t even the best ever in Mets history.” I’ll address the current Tom Terrific vs. Jake the Great comparisons later in this essay, but that Twitter exchange provides the ideal segue into the case that I’m about to make that (and yes, I realize I’m not completely objective here):

TOM SEAVER IS THE GREATEST RIGHTHANDED PITCHER IN BASEBALL HISTORY.

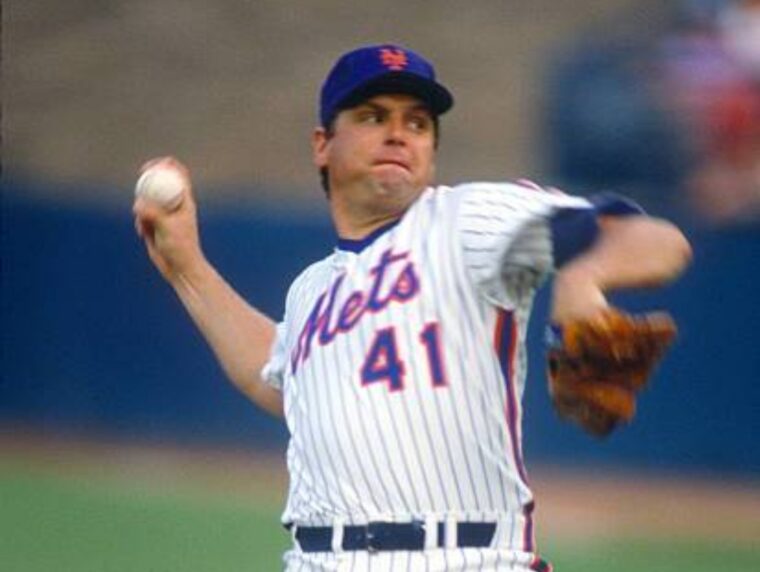

The first time I presented this thesis was in July 1988, in the late, great alternative New York newspaper The Village Voice the week the Mets retired Seaver’s #41 at Shea Stadium.

Writing a revised version 32 years later, my opinion hasn’t changed, even considering that recent Hall of Famers Greg Maddux, Pedro Martinez, and Roy Halladay, and faux Hall of Famer Roger Clemens are new variables in the “Greatest Righty Ever” debate mix.

Frankly, I could end this discussion right now by just quoting Bill James, the Godfather of Sabermetrics. In the 2001 revised edition of his Historical Baseball Abstract, perhaps the greatest baseball book and ranking of players ever written, James ranked Seaver as the sixth greatest pitcher of all-time behind Walter Johnson, Lefty Grove, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Cy Young, and Warren Spahn. James also ranked Seaver third on his “career value” list of the 30 greatest righthanded starters, behind Johnson (416 wins) and Young (511), and ahead of Alexander and Christy Mathewson (373 wins each).

Cue the comparison of baseball players from different eras. I don’t see how any pitcher who threw in the first two decades of the 20th century–the dead ball, pre-slugger, pre-black era– could be considered superior to someone who compiled Seaver’s statistics pitching to the bigger, stronger, faster, and more skilled National Leaguers of the late-1960s to mid-1980s, an era which boasted many of the most prolific sluggers, hitters, and base stealers in baseball history. In fact, here’s what James wrote about Seaver in his 2001 Abstract:

“There is actually a good argument that Tom Seaver should be regarded as the greatest pitcher of all time. Of the five pitchers rated ahead of him, four pitched before World War II, the other just after World War II. Three of those four had their best years before World War I, at a time when big pitchers dominated the game much more than they do now.”

“Since no one can say with any confidence how much tougher the game has become, it is certainly reasonable to argue that the accomplishments of early pitchers should have been marked off by more than I have discounted them, and thus that Seaver’s record, in context, is more impressive than Walter Johnson’s.”

But the baseball player comparison game is almost as much fun as watching old footage of Tom Seaver pitching so let’s play, shall we?

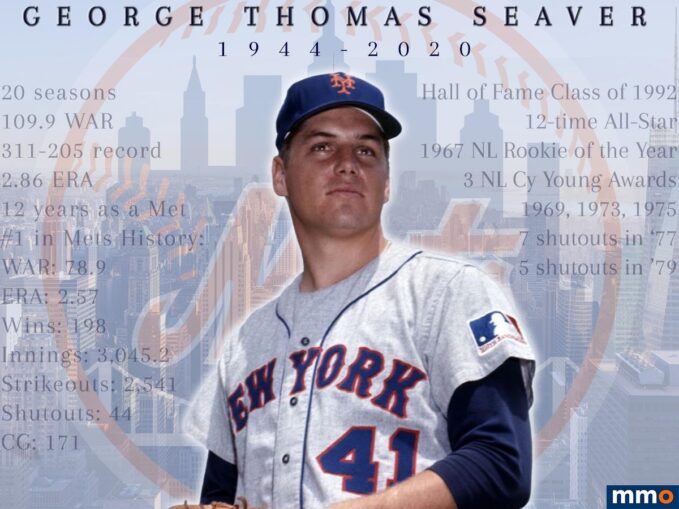

The true measure of Number 41’s greatness lies in how the pitcher with the picture perfect delivery and who won 311 games (18th all-time), struck out 3,640 (sixth), threw 61 shutouts (seventh), and is the only pitcher to debut after 1920 to notch 300 wins and a sub-3.00 era, stacks up against his contemporaries who are or will be in the Baseball Hall of Fame and even active righthanded pitchers who are on a Hall of Fame track.

You can scratch Don Drysdale (209 wins), Catfish Hunter (224 wins), Juan Marichal (243 wins), and Ferguson Jenkins (284 wins, but 226 losses and a 3.34 ERA). The same goes for Don Sutton, Phil Niekro, and Gaylord Perry. Each of those three won a few more games than Seaver, but none had better winning percentages or surpass Tom in any other major category.

And as opposed to Sutton and Niekro, who never won a Cy Young Award, and Perry, who won two, Seaver nailed down three Cy’s himself and arguably deserved one more. I’m still pissed about 1971 when, despite Seaver’s 1.76 ERA and 20 wins, the award went to Jenkins (2.77 ERA, 24 wins) because the voting baseball writers wanted to reward Fergie’s cumulative achievements and pitching wins were valued much more than they are today (more on that later).

Then you have Nolan Ryan, Bob Gibson, and Jim Palmer. Without question, Ryan possessed the best righthanded arm of all time, but his lifetime winning percentage was only slightly above .500. He never won the Cy Young, won 20 just twice, and beats his buddy Tom in only three categories: no-hitters (seven to one), hits-to-innings pitched ratio, and of course, strikeouts.

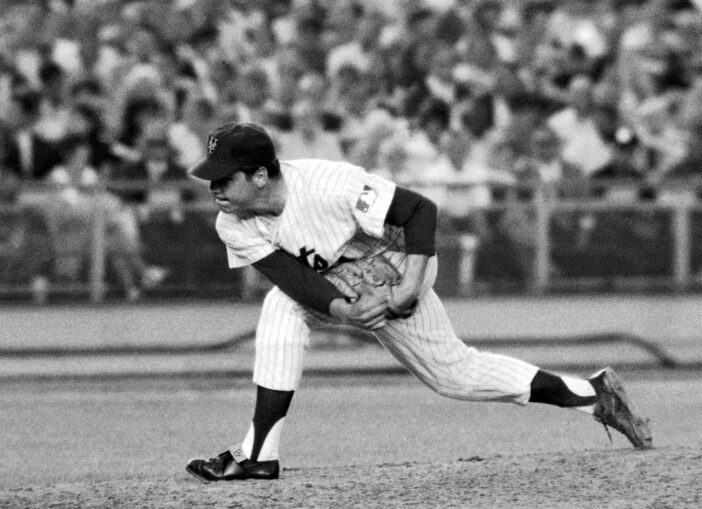

But it’s Seaver, not Ryan, who holds the record for the most consecutive seasons of striking out 200 or more hitters (nine). And if the odds against pitching a no-hitter are high, how about the odds against striking out the last 10 hitters in a row in a 19-strikeout game, as Seaver did on April 22, 1970 against the San Diego Padres.

Bob Gibson won 251 games and for the eight years between 1963 and 1970 he may have been the most dominant righty ever (his 1.12 ERA in ‘68 is still THE single-season record).

One fascinating Seaver/Gibson stat finds that each threw 35 shutouts on the road, tied for the most by any pitcher since 1920. Jim Palmer (268 wins) won 20 games eight times (more than any hurler of the era), won three Cy Young Awards, matched Seaver’s lifetime 2.86 ERA, and compiled a better winning percentage (.638 to .603).

But one statistic that clearly establishes Seaver’s superiority over all his contemporaries is the difference between the pitcher’s winning percentage and his team’s. Tom’s lifetime winning percentage was approximately 120 points higher than his team’s.

Palmer never pitched for an under .500 team. Gibson’s clubs played under .500 when he didn’t pitch just five times. Nolan Ryan didn’t exactly pitch on powerhouses, but he was rarely able to overcome his team’s weaknesses.

If Tom Terrific had pitched for run-scoring teams most of his career or if he’d pitched on a team with a DH, he might have flirted with Christy Mathewson’s and Pete Alexander’s 373 wins. As Bill James pointed out, “Seaver pitched for eight losing teams, several of them really terrible, and four teams which had losing records except when Seaver was on the mound . . . Seaver was dragging his teammates to victory to a larger extent than any of his contemporary stars.”

As much as any pitcher ever, Tom Seaver was the hurler you’d want to go to WAR with, literally and figuratively. The pun was intended. As most baseball sabermetric aficionados know, WAR or “Wins Above Replacement [Player]” has become the gold standard stat with which to value players and attempt to calculate a player’s total contributions to their team in one statistic. WAR basically examines a player and determines how much value would the team be losing if that player got injured and their team had to replace them with a minor leaguer or someone from their bench.

The night Tom Seaver’s passing was announced, MLB.com baseball writer Andrew Simon revealed that since baseball’s “integration” of Black players in 1947, Seaver is one of only seven pitchers to have multiple 10-WAR seasons (1971 and ’73) and only two of those were righthanded pitchers (Gibson and Roger Clemens). In modern baseball history (since 1900), 58 different pitchers have had at least one 5-WAR season at age 22 or younger and 11 have done it at age 40 or older. Tom Seaver is the only pitcher ever to do both.

Simon also reminded his readers that Seaver holds another record that is one of my favorites and one that likely will never be broken. Tom’s 16 Opening Day starts are two more than Steve Carlton, Randy Johnson, Walter Johnson, and Jack Morris. That run included a 12-year streak of Opening Day starts—tied for the second longest ever for a pitcher—which began in Seaver’s second season in 1968. The Terrific One made his final Opening Day start for the Chicago White Sox in 1986—when he was 41.

Now we come to the five righthanded pitchers who have been inducted into the Hall of Fame during this century—Greg Maddux, John Smoltz, Pedro Martinez, Mike Mussina, and the late Roy Halladay—and the one who hasn’t been, namely Roger Clemens.

When James’ 2001 Abstract was published those hurlers were still in mid-career. James had ranked Clemens 11th, Maddux 14th, Martinez 29th, and Smoltz 87th. Mussina hadn’t made James’ Top 100 pitchers list, but was on his radar given he’d already had 132 wins by his age 31 season.

I’m betting that if James published a 2020 edition of the Historical Abstract, both Smoltz (one Cy Young Award, two strikeout titles, and a stellar career as both a starter and a reliever) and Mussina (who never won a Cy Young Award, but compiled 270 career wins and an 18-year career of consistent excellence) would rank somewhere between 20th-30th all-time.

By 2001, Roy Halladay had only pitched for three years and didn’t have his breakout season until 2002, the year before he won the first of his two Cy Young Awards (one in each league). Given Halladay’s 203 wins, .659 winning percentage, and four innings pitched titles, and that he led his league in complete games seven times in a nine-year span (between 2003-2011, when CGs were starting to become extinct), he’d also probably rank somewhere between the 25th-40th best ever. Needless to say, while those three righties were wonderful, none of them were close to Seaver-esque.

That leaves Maddux, Martinez, and Clemens. Let’s deal with the elephant in the room on steroids first and get him out of the way. It’s ironic that when Clemens started his career with the Boston Red Sox in 1984, he was already being compared to a young Tom Seaver.

It’s also ironic that when Clemens won his first Cy Young Award and the MVP with the Red Sox in 1986, Seaver was his teammate in what would be the final year of Tom’s career.

By the time Bill James published his 2001 tome, Clemens had won five Cy Young Awards (he won his 6th that year), six ERA titles, five strikeout titles, and twice had a WAR of over 10 (1990 and 1997). While ranking Clemens 11th all-time, James wrote: “Like Seaver, there is actually a very good argument that Clemens is the greatest pitcher who ever lived.”

But a scanning of the index in James’ book will not show any reference to “steroids” or “performance enhancing drugs.” After compiling Hall of Fame-track statistics and winning three Cy Young Awards during his first 13 years, Clemens struggled through four mediocre (for him), injury-plagued seasons between 1993-96, the last year being his free-agent season.

Then suddenly, at age 34, Clemens was a superstar again and won four more Cy Young Awards, the last one in 2004 at age 41. Isn’t it a coincidence that Clemens’ use of PEDs reportedly began in 1997-98 and continued through the early 2000s.

Even had steroids been in use during the latter part of Seaver’s career, he’d probably cut off his right arm before he’d inject himself with the juice.

As writer Saul Wisnia pointed out in a 2012 article for BleacherReport.com, if you assume a “clean” Clemens from age 34-41 and replace his statistics with Seaver’s over the same period, “the Rocket’s record drops from 354-184 to a less glittering 279-112, and he winds up with three, rather than seven, Cy Young Awards.”

According to Wisnia, those numbers would still make Clemens a Hall of Famer, but perhaps not on the first ballot. Hence, Roger Clemens is eliminated from consideration as the greatest righthanded pitcher ever.

Although there’s no evidence he ever used PEDs, Pedro Martinez was considered baseball’s best pitcher during “The Steroid Era.” During the seven years between 1997-2003, Pedro won three Cy Young Awards over four years (and was 2nd when he “lost”), won the AL ERA title five times, led the league in strikeouts three times, and in WHIP (walks and hits to innings pitched) five times (six times over all). He won the pitching “Triple Crown” (wins, strikeouts, and ERA leader) in 1999, and is 7th all-time in winning percentage. During his prime, Martinez dominated his league like a righthanded Sandy Koufax. Definitely Hall of Fame worthy, but not quite the greatest righty ever on a Seaver level.

If there is one Hall of Fame hurler of the modern era who could challenge Tom Terrific as the Greatest Righthanded Pitcher of All Time, it would have to be Greg Maddux, who although not a power pitcher like Seaver, was also an artist on the mound. Also, like Seaver, Maddux avoided any major arm injuries during the long prime of his career, which helped him compile those 355 wins in 23 seasons (against Tom’s 311 in 20 years).

Maddux managed one more Cy Young Award than Seaver, but “Tom Terrific” beats “Mad Dog” in almost every other significant pitching measure, including lifetime ERA (2.86 to 3.16), WHIP (1.121 to 1.143), Complete Games (231 to 109), Shutouts (61 to 35), Strikeouts Per Season Avg. (190 to 154), 20-win seasons (5 to 2), All-Star Games (12 to 8), and WAR (109.9 to 106.6). I don’t think Maddux’s 18 Gold Glove Awards, while incredible and historic, puts him over the top.

That brings us back, Mets fans, to Jacob deGrom, who along with fellow righthanders Justin Verlander (two Cy Youngs), Max Scherzer (three Cy Youngs), and perhaps Zack Greinke (one Cy Young), have the best shots at future Hall of Fame consideration. That deGrom could be in the Hall mix given that he only has 70 lifetime wins at the age of 32 tells you all you need to know about how much how pitchers are judged has changed in just the past few years. By the end of this season, deGrom could have won a third Cy Young Award and not even won 30 games total to do it.

Of course, Jake should already have more than 100 lifetime wins. In just six plus years, deGrom already has 60 no-decisions. You want some perspective on that? Tom Seaver pitched on Mets teams with brutal offenses and in 12 years had 73 no-decisions. Believe me, I identify with any young fan who idolizes Jacob deGrom and has had to suffer watching him pitch his heart out without finding Ws on Jake’s ledger. I remember countless, agonizing games when my hero would enter the late innings with the game tied 1-1 or he was losing by one run in a low-scoring game. I sweated and paced in front of my TV, praying for the Mets to score, only to see Seaver yanked for a pinch-hitter in the eighth or ninth inning. Yes, I know, thanks to pitch counts, you don’t even get to see deGrom get that far.

But you do get to see deGrom during his prime when he is pitching very Tom Seaver-like, in some cases even better. I never thought I’d see another Mets pitcher dominate other teams during a season or for a string of seasons as Seaver (or Dwight Gooden) did between 1969-1975. While deGrom would have to pitch at an All-Star level for the next five to seven years to come close to some of Seaver’s Mets career numbers (not counting complete games, shutouts, or strikeouts, which are beyond reach), he has been equally as impressive as Tom in some significant ways.

As WFAN/CBSsports.com writer Jason Keidel recently observed, as Mets they both have almost identical career ERAs and WHIPs. deGrom has 10.3 strikeouts per nine innings to Seaver’s 7.5, deGrom currently boasts a better strikeout to walk ratio, and has thrown fewer walks per nine innings.

“There’s no doubt it’s harder for starters to dominate these days,” wrote Keidel. “deGrom has also faced hulking [if not juicing] hitters. He pitches in comically small ballparks. And he’s hurled baseballs that many believe were tweaked to turn fly balls into long balls. Despite these modern hurdles, deGrom tied Bob Gibson for the most consecutive quality starts in MLB history, with 26. Not even No. 41 did that.”

Well, how about that? Someone finally found a flaw in Tom Seaver, the Greatest Righthanded Pitcher in Baseball History.