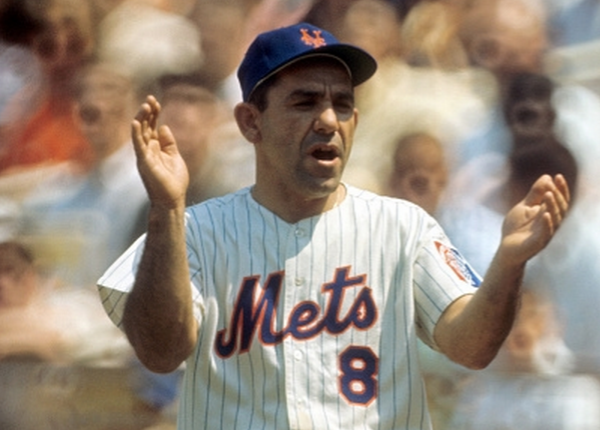

Yogi Berra.

We’re looking back at the 50th anniversary of the Mets’ 1973 National League pennant-winning team by examining the most inspirational figures of that remarkable run. We continue with the leader of this club, a Hall of Fame catcher known for his exceptional play and unique sayings to become a New York baseball legend and an American icon.

By 1973, no baseball fan didn’t know Yogi Berra. It would’ve been hard to think of many living beings who didn’t know of him. Berra was beloved in the Big Apple and beyond for being on countless championship teams with the Yankees, his remarkable play at catcher, and his unique sayings.

Of all the famous quotes he allegedly said, the most notable might be: “it ain’t over ’til it’s over.”

A possibly apocryphal story claims it originated while in the middle of his team’s attempt to move up the National League East ladder a half-century ago.

Berra’s role as Mets’ manager began under tragic circumstances. Gil Hodges succumbed to a heart attack days before the start of the 1972 season. Berra, who served as a coach under Hodges, was reluctant to take the role of a man who led the Mets to the 1969 championship.

After some convincing from his wife Carmen, Yogi took the job. The Mets played at an inspired level, jumping out to a big lead on Pittsburgh before injuries did them in. Rusty Staub, Cleon Jones, and Bud Harrelson (among others) were out for significant parts of the season and the Mets fell out of the race but 10 games over .500.

The following season appeared to be charting a similar course. As the injured list mounted, the Mets’ chances got worse. On July 8, they were 12.5 games back. Despite not having all the resources at his disposal, some felt Berra was to blame for the team’s demise. As late as Aug. 30, the Mets were 61-71 and in last. Luckily, the rest of the NL East wasn’t running away with it.

Finishing 21-8 with a final record of 82-79 proved to be enough to take the division title. But as challenging as leaping over the entire division in September was, an equally daunting task awaited. The Cincinnati Reds made the World Series in 1972 and there was every reason to think they’d return. Berra and the Mets got in the way of those plans.

By taking the NL pennant, Berra became just the second manager to guide a team to the Fall Classic in both leagues, joining Joe McCarthy. Nine years earlier, Yogi managed the Yankees to the World Series. That time, he lost to the Cardinals in seven. This time, he’d lose to the Athletics in seven.

New York gained a split after winning in a wild Game 2 at Oakland Coliseum, which was notable for his argument on an out call at home plate on Harrelson’s attempt to score on a sacrifice fly.

Many feel one decision was costly in determining the Mets’ final fate. Tom Seaver pitched with a sore shoulder as the playoffs began yet performed well in two starts. He was victorious in the deciding fifth game, meaning he would only be available for two World Series appearances. Seaver got the ball for Game 3, went eight innings, and struck out 12 in a no-decision.

The Mets took the next two at Shea and carried a 3-2 edge as the series shifted back to Oakland. With the luxury of a series lead, Berra weighed his options. He could go with his best, Seaver, or his freshest, George Stone—12-3 during the regular season—and preserve “The Franchise” an extra day if Game 7 presented itself. Berra played his ace and paid the price.

Seaver pitched well over seven innings, allowing two runs. His opponent, Catfish Hunter, pitched better—one run over 7 1/3 innings. The result of that day and the next (both in Oakland’s favor) made the decision dubious, forever fostering debate as to whether the alternative would’ve led to a different outcome.

Berra stayed on as manager until August 1975 when he was replaced by Roy McMillan. In three-plus seasons, Berra went 292-296. Yogi could never replicate 1973 and, honestly, it would’ve been hard to.

He often doesn’t get the credit he deserves for this season. Game 6 has plenty to do with it, and perhaps winning with many of Hodges’ players as well. It doesn’t matter who was there before him and the lack of competition his teams faced down the stretch, leading a team from last to the precipice of a title is certainly worth recognizing.