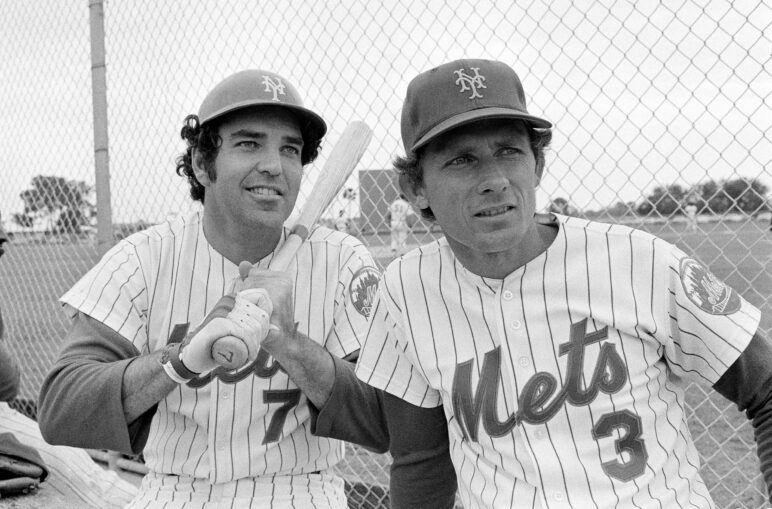

Bud Harrelson, Ed Kranepool.

We’re looking back at the 50th anniversary of the Mets’ 1973 National League pennant-winning team by reviewing the most inspirational figures of that remarkable run. We continue with the only person in uniform for both of the franchise’s World Series titles and remains one of the most beloved Mets ever.

Look at the stat sheet for Bud Harrelson and you won’t see his true impact. The Mets of the late 1960s and early 70s were heavily dependent on superb pitching and solid defense. For where he played in the field, Harrelson was a valuable component of the team’s mindset.

And if you saw his 5-foot-11, 160-pound frame standing at shortstop, you might not immediately think of toughness. But that’s what Harrelson brought on a daily basis. He had to earn everything—and fight for it (literally) when needed. By the time his time in a Mets uniform was finished more than 25 years after it started, he’d have two rings and been a part of the most successful teams in franchise history.

While Harrelson’s limitations at the plate were undeniable—a 16-year career batting average of .236 with seven home runs—his importance as a fielder was tremendous. The glue that kept the Mets’ infield together and the glove his pitchers could trust, Bud finished with a lifetime fielding percentage of .969.

As Tom Seaver once said, “Having him playing at shortstop every day is like having a top-notch pitcher. It keeps you out of a losing streak.”

Harrelson’s outstanding glove work and significance to a team built on pitching and run prevention were gaining attention as the Mets rose out of the pits and into prominence. In 1970, he set a then-major-league record of 54 consecutive errorless games at shortstop—the same year as his first All-Star selection. He’d make the Midsummer Classic again as a starter in 1971 and ended the year with a Gold Glove award.

But it wouldn’t be long before Harrelson was finding it difficult to withstand the rigors of a full season. He missed 300 games over the next six years due to damaged hands, sternum, back, and knees. He never played in more than 118 games and just once in that span did the Mets return to the playoffs, which also happened to be the year his feistiness and unwillingness to back down gained notoriety.

Harrelson was swept up in the tidal wave of injuries that threatened to cast the Mets’ 1973 season adrift. His presence—or lack thereof—in commanding the infield was noticeably felt. During two separate stints on the disabled list, the Mets were 23-36. With Harrelson, they were 59-43. Luckily for New York, he was there when it mattered, and so were most other key contributors. Propelled again by great pitching and sturdy defense, the Mets won 19 of 27 in September and took the NL East despite an 82-79 record.

Held hitless in the NLCS opener with the Reds, Harrelson produced a single and an RBI in a 5–0 win that evened the series. That was more than could be said for Cincinnati’s entire Game 2 output. He chided afterward that Reds hitters more resembled him than the Big Red Machine. And that was the impetus for what would transpire in the fifth inning of Game 3.

The Reds sought to get even in Game 3, and Rose was set to carry out that vengeance when he slid hard into Harrelson covering second base on an inning-ending double play. Bud instantly objected to the malice. Rose shoved. Harrelson shoved back. It was on from there. Both teams hustled to the scene. A few punches were thrown. Some uniforms were dirtied. Several feelings were hurt. But nobody was ejected.

The closest either came to an early departure was when the Shea crowd pelted Rose with litter as he took the field in the inning following the fight. The insanity in the stands subsided enough for the continuation of the game—a 9–2 Mets win that put New York one victory from the pennant.

Rose’s 12th-inning homer the next day extended the series to its limit, but the Mets prevailed—meaning a meeting with the defending champion Oakland A’s. It offered Harrelson another chance to put his feisty demeanor on full display.

Harrelson prepared to score the go-ahead run in the top of the 11th of Game 2 on a Félix Millán fly ball to left field. As he approached home plate, he resisted the slide and evaded the tag of catcher Ray Fosse.

Umpire Augie Donatelli thought otherwise, prompting Harrelson and a cavalry of Mets to angrily dispute it. As instant replay showed they had every right to vent their frustration, and since this was 1973 and not 2023, the Mets could only stew in their disdain—though not for long.

Harrelson began the top of the 12th with a double—his third hit in six at-bats—moved to third on Tug McGraw’s bunt single, and scored on Willie Mays’s single. The Mets added three more to prevail in what was, at the time, the longest game in World Series history.

After the series loss to Oakland, it would be 13 years before the Mets made another playoff trip. Bud would be there for that one too, serving in a much different role as third-base coach. He’d eventually become the bench coach and manager by 1990.

Harrelson remains on the team’s top-10 list in games played, at-bats, hits, triples, and stolen bases. He succeded in his many battles on the field. His current opponent, Alzheimer’s disease which was diagnosed in 2016, is as difficult as they come. But as we’ve learned for more than 50 years, Bud Harrelson doesn’t go down without a fight.