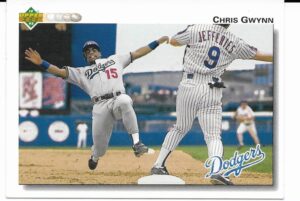

Often we take a look at cards featuring Mets stars and marvel at the action shown on the card. At times we are satisfied to determine the game and play of the action showed on the card front. In this article we’re going to do things a little differently as we review together this 1992 Upper Deck (card #689 from the set) that features Chris Gwynn sliding into third, which is manned by Gregg Jefferies.

First, let’s get our Sherlock Holmes deerstalker hat off the wall and avoid shaking our head in dismay at the action in progress so we don’t dislodge the hat from on top of our head.

What we see in the card is a day game at Shea Stadium from the 1991 season between the visiting Dodgers and the Mets. Note the ramp to the train in the background, which allowed a nice view of game action to those who left the game before it finished to turn around and watch from afar. Checking the Mets’ Schedule & Results page for 1991 on Baseballreference.com, we can see that the Dodgers played six games at Shea that season, visiting Shea May 7 and 8, but both were midweek night games.

The Dodgers next visited Shea July 18-21, but the games on the 18th and 19th were both night games and can therefore be eliminated. A check of the box score from July 20th shows that although Gwynn and Jefferies both played in that game, Gwynn never reached base and Jefferies played second, so that game can be eliminated.

By process of elimination, we can conclude that the Sunday day game of July 21st is the game from which the action shot was taken.

Reviewing the play by play provided by baseballreference.com, we can see that in the top of the second, after a single by Lenny Harris, which scored former Met Darryl Strawberry, Gwynn was on second and Harris first when left hand-hitting catcher Mike Scioscia grounded weakly unassisted to third off of Dwight Gooden for the first out of the inning. This is the play seen in the card shown here.

Let’s take a closer look at the card, and note sadly:

- Jefferies has his left foot on the front of the bag, and is throwing to second in a side-arm motion, while falling away from his throw.

- The Mets second baseman, who the box score shows was Keith Miller, is no where near the bag at second despite a right hander at the plate and a ball hit weakly to third has already been fielded and the third baseman is ready to throw the ball.

- In the distance, is the Mets right fielder who has his arms at his side and is not moving. The right fielder that day was Hubie Brooks.

Proper technique by Jefferies would be to shield his foot on the backside of the bag. Any little league coach would have taught him to throw overhand while stepping towards his target. Properly positioned for the double play, and assuming every ball is fair and therefore covering second at the moment a ball is hit to the left side of the infield, Miller should already be at second (or at least in the picture) to force the base runner Lenny Harris, who is not even seen in this picture.

Further, right fielder Hubie Brooks, rather than standing still and catching some rays on the 98 degree sunny day, should be lined up behind second to back up the play in case of an overthrow. Bad fundies as Mets announcer Keith Hernandez would say.

As a result of these bad fundies, the Mets did not turn the double play. Unable to complete the double play at second, after the next batter (Alfredo Griffin) walked, the subsequent fly ball by former Mets pitch Bobby Ojeda was only the second, rather than the third, out of the inning and Harris tagged up and scored.

The Mets did come back on the day, scoring 2 in the bottom of the second and 6 in the third to chase Ojeda and win the game 9 – 4, putting the Mets 15 games above .500 and 4 games behind the Pirates. However the remainder of the 1991 season was not good to the Mets, nor their fans, as the team finished 7 games under .500 at 77 – 84 and in fifth place. Manager Bud Harrelson did not finish the season with the team.

Our close analysis of this card hints at the defensive problems the Mets experienced that season. While Gregg Jefferies was bad with the glove at second, costing the Mets 84 runs defensively between 1987 and 1991 at second based on his Total Zone Fielding Runs (or above average errors and below average range for traditional stat users) at third he was worse, with 11 errors in 51 games in 1991 alone. His error total exceeded his double play total, which was only 5.

One can see from the footwork and throwing motion captured on this card why that total was so low. For those who like dWAR, his fielding WAR (dWAR) was negative .7 Translated to runs, his bad fielding theoretically allowed 7 additional runs to score. This card captured one of them. That’s a lot of bad fielding to tolerate for a bat that had a .711 OPS that season, a mere 1% better than league average.

Keith Miller, who hit .280 that season, also had a negative defensive WAR in 1991 of -.7. His .972 fielding percentage was below league average and his range factor per game of 4.62 ball per game was far below the the league average for a second baseman, which was 5.12. So he reached fewer balls than the average National League second baseman, and and when he did reach them, he booted more of them.

Hubie Brooks, at 34 years old, also had a negative dWAR that season (.7) as he registered 5 errors in right despite reaching far fewer balls (1.72 per game vs 2.05) than league average. All three Mets pictured on the card had a -.7 dWAR in 1991, meaning just these three fielders allowed 21 additional runs to be scored against the Mets in 1991.

As we hang our deerstalker hat back on the wall, lets remember that some commentors complain that rather than use defensive WAR measures, or dWAR, they prefer to use their eyes. As shown by this card, many times what the eyes see and what defensive WAR measures, are the same thing.

LGM