If one were to look up the word ‘consistency’ in the English dictionary, rather than reading the brief text that defines the word, a simple picture would better suffice.

In Major League Baseball, it doesn’t take long to envision the player that encompasses this word. This individual exemplified what it meant to be consistent on a day-to-day basis; showing up for each game prepared, ready to lead and putting the team ahead of any personal woes or injuries.

The nagging aches and ailments of a baseball season can be daunting, in which your body is your temple and you hope to preserve as much physical and mental strength in order to withstand the rigors that come with being a professional athlete.

Fans judge players by how often they stay on the field and produce, for their production value is aligned with their ability to remain relatively healthy throughout the course of a season. Managers look to keep their players fresh, providing off days and doing everything to ensure they maximize as much health and vitality as possible.

For Cal Ripken Jr., the model of consistency, sitting out a game was simply not an option.

Ripken, 57, was far too valuable to sit, as he established himself as a consummate player on both sides of the ball. Gifted with power and size, a keen plate discipline and a tremendous defensive acumen, Ripken revolutionized the shortstop position at a time when it was regularly filled by smaller statured, defensive-minded players.

According to Baseball-Reference, Ripken is the only player to post 1,000 or more extra-base hits while compiling a defensive WAR (dWAR) of 30.0 or greater for his career. A true testament to the power and defensive capabilities Ripken displayed throughout his twenty-one year, major league career.

On May 30, 1982, Ripken appeared in the Orioles’ lineup playing third and batting eighth. Nobody could’ve imagined that he wouldn’t take a day off until September 20, 1998, an incredible streak of 2,632 consecutive games played.

For that accomplishment, Ripken’s name will forever be synonymous with that of Hall of Fame first baseman Lou Gehrig. It was Gehrig who established the previous all-time mark of 2,130 consecutive games played in 1939, a record many historians thought would never be broken.

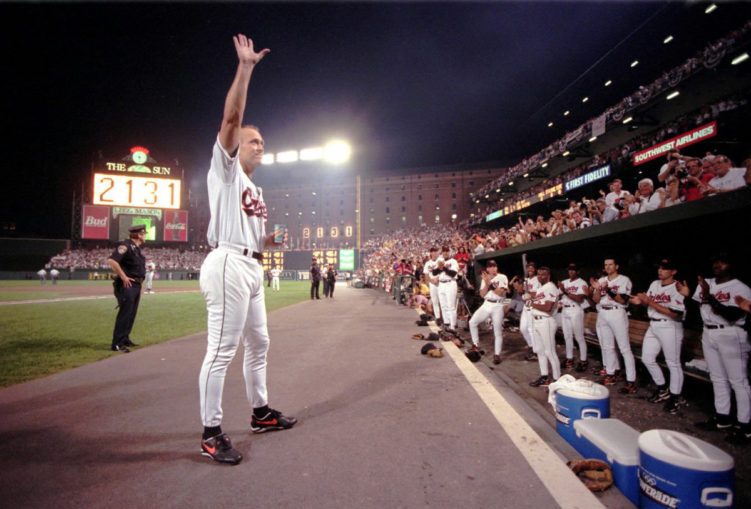

Fifty-six years later on September 6, 1995, Ripken surpassed that mark, playing in his 2,131 consecutive games. What transpired in the bottom half of the fifth inning was a celebration even Ripken could not have envisioned, as the game came to a halt as the sellout crowd that included Bill Clinton, Joe DiMaggio and his father, Cal Sr., stood in honor of what’s considered baseball’s greatest milestone.

Iron Horse, meet the Iron Man.

Ripken played all twenty-one seasons with Baltimore, appearing in nineteen All-Star Games (third-most all-time), winning two A.L. MVP Awards (1983, 1991), Rookie of the Year honors (1982), eight Silver Sluggers, and one World Series championship in 1983.

He is one of just eleven players to amass 3,000 or more hits and 400 or more home runs for his career, a list that includes Willie Mays, Stan Musial, Hank Aaron, and one of Ripken’s closest friends: Eddie Murray.

Ripken was enshrined in the hallowed halls of Cooperstown in 2007, receiving 98.5 percent of the vote which is the fifth-highest percentage behind only Mariano Rivera, Ken Griffey Jr., Tom Seaver and Nolan Ryan.

His character, integrity and passion for the game will never be lost on fans, as the streak came at a time when fans were rightfully irate over the strike in 1994. Ripken understood the importance of what his accomplishment meant in bridging the gap between ballplayer and fan and took it upon himself to be a beacon of hope to draw the fans back to the game.

The countless hours he spent interacting with fans and acting as an ambassador for the sport will never be forgotten, as Ripken’s legacy is forever embedded in baseball history.

I had the privilege of speaking with Ripken in late March, where we discussed his latest partnership with Roy Rogers Restaurants, whether he views himself as a trailblazer for the taller, stronger shortstops that have debuted in the league and his thoughts on his consecutive games streak.

MMO: Who were some of your favorite players growing up?

Ripken: Brooks Robinson was the key guy. I grew up here in Baltimore and not only was he a great player and a clutch guy, but he was really exciting. Like most kids around the area, everyone wanted to play third like Brooks and come through in the clutch like Brooksie. He was my guy.

The Orioles as a team were really good and they had many stars on it, but Brooksie was my main guy.

MMO: You wrote in your 1998 book, The Only Way I Know, that you pitched during your youth and that scouts were viewing drafting you as a pitcher. Do you feel that you could’ve had a successful career as a major league pitcher?

Ripken: Well, you never know. I think the Orioles might’ve been the only team that was interested in me playing as a regular player, but even then the Orioles had issues within their organization and a lot of people said I should pitch.

I remember my dad playing a diplomatic role in that decision because he was a lifelong minor leaguer that developed players. He would say, “When we had a player we were unsure about, we’d start him as a regular player and you can always go back to pitching. But if you start him pitching it didn’t work that well in reverse.”

I think Dad was setting it up for me to actually have an opinion of my own and I remember Hank Peters [former Orioles GM] asked me, “What do you want to do?”

I said, ‘Well, pitchers get to play one out of every five days, so I want to play every day.’

I had really good stuff and I struck a lot of people out. I had a good fastball, good command of my breaking ball and had a good changeup. So I don’t know.

It was funny, when I played catch with Mike Boddicker when we got drafted and we were just throwing different pitches, he laughed and said, “Damn, you’ve got better stuff than I’ve got!” (Laughs).

But who knows. You never know if you could’ve done it or not, but sometimes I wonder what it would’ve been like if I had a chance to be a pitcher.

MMO: You write in the book about how you kept detailed notes while playing in Bluefield [former Orioles minor league team] on all the pitchers and their sequences. You write that no one else was doing this and you kept doing so until the Orioles coaching staff started including them in their info they prepared for the media years later. Was that something you learned to do from your father, and how beneficial was that for your development early on?

Ripken: Yeah, my dad. I guess it was all part of figuring things out and I was very analytical. My dad suggested that when you face these pitchers and as you move up you might face them many more times in future years. It wasn’t easy to remember so you’d take time to write their name down and put the sequences in, which started to get you to understand how things worked.

When they threw certain pitches it started to create patterns and that became a real important part of my hitting, as until you get to two strikes you wanted to look for a pitch that you wanted to hit, the type of pitch and the area that you wanted to hit it in. That was the early start to that and I might still have those little books around somewhere.

MMO: July 1, 1982, was the date you walked into the clubhouse and saw your name penciled in at short. What were your initial reactions to the move, and did Earl Weaver say anything to convince you on the switch mid-season?

Ripken: You know, no. It’s funny, my dad and Lenn Sakata gave me sort of a heads up on the day of that I was moving to short. It wasn’t one of those call me into the office and say we’re thinking about doing this [type of thing]. I did go into the clubhouse and took a glance at the lineup, just to make sure I was in there. Instead of having a five next to my name, there was a six.

My initial feeling was Earl [Weaver] had just made a mistake and wrote it down wrong. Then Lenn Sakata came up to me and said, “You’re playing short.” And then my dad said, “Yeah, you’re going to play short.”

I was a little fearful and then Earl called me into the office and said, “Look, I don’t want you to try and do anything fancy. If the ball is hit to you I want you to catch it, get a good grip on the ball, and make a good throw to first base. And if the guy beats it out he’s only on first.” (Laughs)

It was his way of saying don’t try to make it more complicated than it is.

I had played short in the minor leagues for the first year and a half and went to instructional league as a shortstop, then halfway through the A-ball season, I played third. Going back there I had a more advanced understanding of the speed of the game and it was easier going back, but I didn’t know that at the time.

MMO: Players like Derek Jeter and Alex Rodriguez have been quoted saying that you paved the way for bigger, taller shortstops. What is your view on that subject and do you view yourself as a type of trailblazer for the wave of taller shortstops we’ve seen come up and succeed at that position?

Ripken: I don’t look at myself as a trailblazer necessarily. But I think the success that I had at the position – being a taller person – might’ve changed the mindset because the mindset was pretty firm. They were looking for defense, they were looking for these smaller guys up the middle that could cover ground.

To me, it’s the basketball analogy; I was a big basketball fan. If you think of Magic Johnson running the point at his height, all of a sudden that made people turn their head and go, man, if he can do that he can pass to the post, he can see over the guy’s guarding him, he can do a number of things.

I think my success at shortstop might have changed some mindsets a little bit. I think Derek or Alex both would’ve come in and paved their own way. I do think maybe the mindset was changed a little bit and at least you were considered staying at a position like shortstop a little longer and seeing how they develop.

MMO: Throughout your career, you had many different batting stances and starting points to get your timing down with your swing, including one of my favorites, the violin. I’ve heard you in the past talk about getting the right feel, is that why you altered your stances throughout your career?

Ripken: I did hit on feel and there are certain fundamental mechanics that I did no matter what stance I had. You end up loading and taking the bat back and coming through all at once, but there are different starting positions. When I played sometimes I couldn’t make it work and in BP it didn’t feel right.

I would make adjustments and if I made an adjustment and all of a sudden something clicked just because I changed my starting position, then I would play that out a little bit. I wasn’t afraid to do that but I think in the end if you’re making an analysis or you’re analyzing my swing, people looked at the starting position and said, “Wow, that’s different.”

If you looked at the point of contact or when the pitcher was releasing the ball, you would see that the position that I got myself in is very similar to all the other ones. It was just the way I hit and sometimes I needed a new starting point to give me a click in my natural way of hitting.

Photo by Karl Merton Ferron/Baltimore Sun

MMO: On September 6, 1995, you broke a record many thought would never fall, surpassing Lou Gehrig for the most consecutive games played, with 2,131. Watching you receive a standing ovation for 10 minutes, fans chanting “We want Cal,” and your teammates pushing you out to take a victory lap, can you talk about some of the emotions you were going through at that moment, and what the fans meant to you then?

Ripken: I never set out to break Lou Gehrig’s record, it wasn’t a lifetime goal of mine. It seemed like I wanted to play and I wanted to play every day and it felt like that was your job to come to the ballpark and play. Once the streak became the streak and it started to get attention when it was around 1,000 games, once it became the streak, I had to try really hard not to think about playing for the sake of the streak.

You just want to keep your approach the same way as it was all the way through. The only thing different is when I got into the last year it became feasible to everyone else that it could be done, and maybe even to myself that I always looked at it from season by season standpoint.

I never saw it as a finish line, and then all of a sudden when they’ve got celebrations set up for the tying and the breaking of the record, all of a sudden there was a finish line. That started to put a little pressure on you like you had to get there for some reason.

Once the 2,130 game was played – the tying game – there was a relief on my shoulders that okay, tomorrow’s going to happen. Then once you got into that game you’re able to enjoy it and play the game. It did have its toll on the expectation of getting to that finish line. I was trying to give more to the fans, I was trying to give more to the media, there was more attention all the way around. Going down the stretch your adrenaline carries you so far but it was pretty exhausting.

The emotions were there to lead up to it, and once it unfolded there’s nobody that could’ve choreographed what was to take place after that. It unfolded in a very normal and natural sort of way that was very heartfelt. I remember I was feeling that I was holding up the game in the middle when it became official, and my thought was, Thank you very much, thank you very much, but let’s go back and play the game. I’ll celebrate it once the game is over.

Then that turned into the lap around the ballpark and then I was thinking, Okay, make a lap around the ballpark and it’ll be the impetus to start the game again. But once I started shaking people’s hands and seeing them face-to-face and eye-to-eye, it took the celebration to another level. It made it more intimate, more personal, and very quickly I couldn’t care less whether the game was continued or not.

When people ask me what’s your best moment in baseball, people assume it’s that one. I quickly say I caught the last out of the World Series [1983] and there’s no other feeling like that, period. Not even close.

From a personal standpoint, a human standpoint, having that experience of 2,131 and the lap around the ballpark was probably the best human personal moment on the field. It was really special in so many ways. Hundreds of ways.

Player’s Tribune

MMO: Many say that your streak helped save baseball after the 1994 strike, and bring fans back. What are your thoughts on that notion?

Ripken: I know that the strike came up pretty quickly and then all of a sudden the season was over and the World Series was cancelled. There were a lot of people that were really upset with the game of baseball. I remember in the first day of spring training we got an early indication of the attention that the streak would [get].

When we came back and there was a shortened spring training we had to really go quickly. You had a sense that people were looking for something to attach themselves to that might make them feel like you’re turning back the clock like you’re going back to when baseball was a game instead of a business, I guess.

I think people could relate to the streak and relate to the hard work ethic that they possessed in their own lives. I think one of the beautiful things about the streak for me and the celebration was having all the people share their streaks with me. I haven’t missed a day of work in thirty-one years, and why it was important for them to show up. Attendance records at high school and people were using it that way and I think that they genuinely related to it as a value. They were able to look inside baseball and see the things that they really wanted to see from it.

I think I was helpful in that regard, it just seemed like it was the right thing at the right time.

MMO: I read that when you decided to end the streak at 2,632 in 1998, your replacement, Ryan Minor, thought it was a rookie prank and didn’t want to go out and take the field. Was that true? And how did you go about deciding that September 20th was the day you were going to sit out?

Ripken: (Laughs) Yeah, he was hesitant to go out there because he thought it was some sort of joke. I had to convince him and say, ‘No Ryan, it’s real. I’m taking off.’ He was just a little delayed in starting.

I waited until ten minutes before the game started to tell the manager. I had decided earlier in the season that if we were to fall out of the playoff run then I was going to end the streak, and my original idea was to do it the last day of the season. To do it almost as a statement that I could’ve played all of them if I wanted to. (Laughs)

Then it turned out that I started to think about it and September 20th was the last home game of the season and we were ending on the road. Everybody had a special feeling about it and I remembered how everyone related to it in 1995, so it was important to make it a positive thing and not run the risk that it would be a negative thing.

I ended it at home and told the manager and everybody responded really positively and it turned out really good. The reason I told them ten minutes before the game was I didn’t want to have it interrupt and affect the team before the game started. It was sort of a way to react to it after the fact as opposed to reacting to it before the game started. I wanted it to unfold more naturally as opposed to forced.

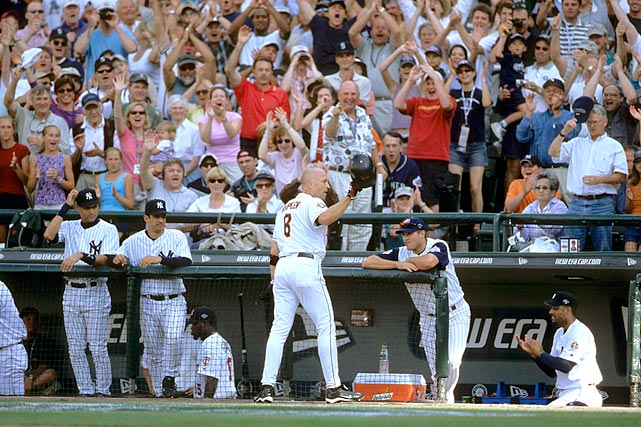

Photo by Sports Illustrated

MMO: One of the lasting memories I have of you was from your final All-Star Game appearance in 2001 at Safeco Field. Two big moments for you were when Alex Rodriguez pushed you towards shortstop for that half-inning in the first, and your home run off Chan Ho Park in the third. Can you talk about both of those moments and what they meant for you?

Ripken: I was excited to be back at the All-Star Game. I had decided to retire earlier on in June. I had come off a shortened spring training because I had broken a rib about ten days before spring training started and didn’t have a complete spring. We were going into a rebuilding mode again and I didn’t get cranking too well. Then all of a sudden I started swinging the bat better and I was voted into the All-Star Game as a third baseman.

I was happy to have a chance to do it one more time, and when we went out onto the field Alex came on over to me and said, “Why don’t you go play shortstop for an inning?”

I wanted to tell him where to go and I said, ‘I’m not doing that.’

I realized we were wired, we had a microphone on and then he pointed and said, “Look at Joe Torre in the dugout.” Joe was pointing me over and then I felt like I was the only one that didn’t know I was going to go play shortstop for an inning.

I didn’t want to be embarrassed or go over there so finally when I went over I remember yelling at Roger Clemens, ‘Looks like you’re going to have to strike out the side now.’ He kind of laughed back, but as I played shortstop I was thinking, It would be okay if I didn’t get a play in this inning and have that be over. And then after the first out, I’m thinking, Well, this feels pretty good, maybe I could get a play. Then I started rooting for one and by the time they had two outs I was hoping a ball would be hit to me.

It was a wonderful tribute and it was Alex’s idea. It turned out to be really heartfelt that I had success for all of those years at shortstop and he was giving me a tribute by pushing me back over there.

The Chan Ho Park homer was I came to bat – I think in the third inning – and I think I led off the third inning because Edgar Martinez was hitting in front of me and he struck out in the second. Randy Johnson had the first two innings and Randy was out of the game and I thought that was a pretty good thing because in the twilight, Randy’s one of the harder ones to pick up. They brought in Chan Ho Park and I’m going, That’s better than Randy.

I remember looking at the backdrop and you couldn’t see anything, and I think I told [Mike] Piazza, ‘Wow, this is way worse than I thought.’ I wanted to hit a ball early in the count and he threw a fastball on the first pitch and I put a nice easy swing on it and connected and it went out of the ballpark.

I think I said my excitement level was much higher than normal, it felt like I was flying around the bases, I was running really fast. It felt like I was fast for the first time in my life and came around and was able to shake hands in the dugout.

It was a really cool moment to be able to deliver in your last All-Star Game like that.

MMO: Your father, Cal Sr., was an instrumental figure in your life, and was a tried and true baseball man. What was the biggest piece of advice he imparted on you, and what was getting the chance to have him as a manager in the late eighties like for you?

Ripken: Dad was a baseball encyclopedia and many players and coaches that were around the game wrote almost the specialty books on how to play. I had access to that whole library. Dad would shape me on how to respect the game and how to play the game and how to go about it.

I try to keep thinking what’s the advice that resonated the most with me, and when I was in the minor leagues he said, “It’s important for you to remember and know that you belong where you are.” And what he was trying to tell me, I think, was to have confidence in yourself, that you’ve earned your way there. Now, you might look around and see other players in different levels of development but measure yourself against everyone else, and then know you belong.

I try to give that advice to my son as he’s gone away and he realized that’s something you have to experience yourself and try to understand. Once you do start to look around and you have the confidence to say, “I can compete, I can play here.” That’s when your development really starts, I think.

MMO: You’ve recently partnered with Roy Rogers Restaurants for their 50th anniversary. Can you talk about your relationship with them?

Ripken: Yeah, it’s interesting. There have been endorsements throughout the years that I’ve been very careful [with] because it has to make sense for me. So I’ve made decisions on that basis. Roy Rogers takes me back to when I was a kid and how I enjoyed a roast beef sandwich, in particular.

It’s also philanthropically such a good match, we’re trying to do good by kids and raising money for the Cal Ripken Sr. Foundation in honor of Dad. This is a mechanism to help raise funds as well. I think the alignment of being the spokesperson for Roy Rogers was speaking my language for their product but also speaking my language for trying to help kids. It’s just one of those that come along and you go, This is a good match.

We’re looking forward to doing right by kids and getting good attention for Roy Rogers.

MMO: Thank you so much for your time today, Mr. Ripken. It was truly an honor to speak with you and talk about your legendary career.

Ripken: I appreciate it. Thank you.

Visit Ripken’s foundation, the Cal Ripken, Sr. Foundation, here.

Visit the Roy Rogers Restaurants website, here.