On July 21, 2004, a 21-year-old top prospect from Virginia made his major league debut for the team he grew up rooting for.

Batting seventh and playing third base, David Wright began a career that seemed destined for eventual enshrinement into the hallowed halls of Cooperstown.

Showcasing extra-base power – with his trademark hits to right-center field – along with good speed on the basepaths, and with charm and charisma that soon made him not only a household name in New York, but the entire Major Leagues, Wright was ascending to superstardom.

From his rookie season in 2004 through the 2013 season, Wright posted the sixth-highest fWAR among position players (48.7). Among 108 players who recorded at least 4,000 plate appearances in that same span, Wright’s wRC+ of 137 was 10th-best.

In 2007, Wright joined Howard Johnson and Darryl Strawberry as only the third different Mets player to post a 30-30 season, while posting the best triple-slash line of his career with a .325 batting average, .416 on-base percentage, and .546 slugging.

The seven-time All-Star and two-time Gold Glove-winning third baseman provided countless memories throughout his fourteen-year major league career, including making a bare-handed, over-the-shoulder catch in San Diego in 2005; hitting a walk-off single off Mariano Rivera in the first Subway Series game in 2006; hitting a home run in the first at-bat of his first All-Star Game in 2006 and hitting a go-ahead, two-run home run off Yordano Ventura in the first World Series game in Queens in fifteen years.

What the Mets received in Wright was just about everything an organization could ask for in a player: a hard-working, well-spoken individual who led with his consistent All-Star play on the field, while being the quintessential team representative in the clubhouse and to the media.

It came as no surprise then, when the Mets officially named Wright the fourth captain in franchise history in 2013, joining only Keith Hernandez, Gary Carter and John Franco. The honor bestowed upon Wright was one in which he looks back fondly on, naming it as one of the proudest moments of his professional career.

Wright’s trajectory was pointing towards an eventual plaque in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, which makes the latter part of his career all the more unfortunate. Wright’s downfall began back in the 2011 season when he sustained a stress fracture in his back in a diving play at third base with Carlos Lee.

While Wright was able to play in 156 games the following season, finishing sixth in the National League MVP voting and signing an eight-year, $138 million extension that offseason, along with posting a 5.2 bWAR in 112 games in 2013, the star third baseman was given unwelcome news in 2015: the diagnosis of spinal stenosis.

What ensued were countless surgeries to his neck, back, and shoulder, along with strenuous rehab and physical therapy sessions. For Wright, ever the committed hard worker, this was not going to define his career.

He wanted to go out on his own terms.

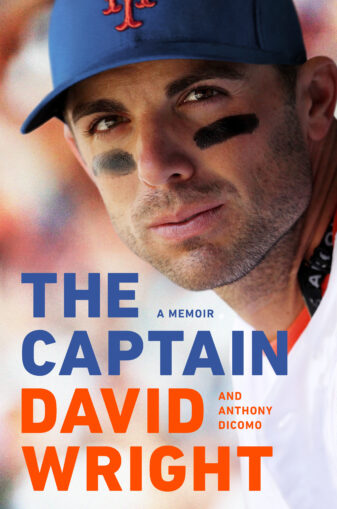

Wright opens up about his life and career in his upcoming memoir titled “The Captain,” (release date of October 13) which was co-written by Mets’ beat writer for MLB.com Anthony DiComo. The book reveals the mental and physical struggles Wright endured to make it back onto the field, which he was able to do late in the second half of the Mets’ pennant-winning season in 2015.

The memoir offers a glimpse into just how arduous Wright’s efforts were to get back to playing the game he so loved. Wright details early on in his book how his father, Rhon Wright, had a chance to leave the hospital for a few hours after David was born, and instead of getting rest, he found himself purchasing a plastic glove, a kid-sized Louisville Slugger and a baseball.

As Wright puts in the early pages of his memoir, “From the time that I could walk, everything on both sides of my family revolved around a ball and a bat.”

Among all-time Mets, Wright is the franchise leader in plate appearances (6,872), hits (1,777), doubles (390), runs scored (949), RBI (970), walks (762), and position player bWAR (49.2), while second in games played (1,585) and home runs (242).

Though the latter part of his career was marred by injuries, Wright will forever be revered by the fan base for posting some of the best single-season performances in club history, his leadership on and off the field, and incredible perseverance to return to the field.

The name David Wright will forever be synonymous with the New York Mets.

I had the privilege of speaking with Wright in early October, where we discussed writing his memoir, the injury struggles he faced, and how important it was to say goodbye to the New York fans.

MMO: David, thanks so much for taking the time today. Talk to me about what prompted you to write the book and what the overall process was like.

Wright: It’s funny, Anthony DiComo approached me shortly after my last game. He was down in San Diego for the general managers’ meetings, I believe. He asked if he could drive up – I’m in Southern California as well – and meet about an idea he had.

I told him, ‘Okay, we can go grab some lunch.’

He came up and said, “Hey, I’m going to write a book and there are three options that you can do. You can have nothing to do with it and I kind of do it all on my own, you can sort of be involved but I’d take the lead, or, we can do this fifty-fifty where we both write it. But that’s going to require a lot of your time.”

I thought about it for a little while and I told him I’d like to go all-in when I do things.

I said, ‘Let’s partner up and do it the right way.’

Dutton

It was a tremendous process and, obviously, with COVID it didn’t allow for some of the in-person stuff that I would’ve liked to do, but we spent dozens and dozens of hours on the phone. And he spent even more time connecting with childhood friends, teammates from amateur ball, the minor leagues and, obviously, the big leagues, and talking to my family and friends.

It was a cool process to go through. I was probably as guilty as anybody during my career of not allowing myself to enjoy the moment, or enjoy steps of my career. When you’re a player, at least for me, it was always onto the next challenge. What can I do to improve? I never got a chance to sit back and watch highlights or big games that we won or things like that.

Going through all of that and combing through it after my career was done put a big smile on my face and allowed me to kind of relive these memories that are some of the greatest that I’m going to have in my life.

I got a chance to pick out thirty or so pictures for the book – personal pictures – and my parents do a great job of organizing and keeping stuff from my childhood. They sent me three of four huge boxes of pictures from when I was born all the way to pictures they took in the stands [of me] in the big leagues. Getting the chance to relive some of those memories was pretty cool.

MMO: Family is something that you write extensively about in your book. Can you talk a little about your upbringing and the values your parents instilled in you to become the man you are today?

Wright: My parents were strict. Being punctual was important, being a good citizen was important, being a good student was important, way more important than being a good baseball player. I’d like to think that’s where I get that blue-collar mentality, that bring your lunch pail to work type mentality.

My dad was a police officer and my mother worked in the school system and it was certainly being a good student and being a good citizen before being a good baseball player.

My dad never, ever said a word to me when I had a bad game and when I struck out three times. I’m not saying he didn’t care, that just wasn’t the important thing; it was how I reacted to both failure and success. If I struck out and hung my head and went and moped in the dugout and didn’t cheer my teammates on, that’s when I’d get a talking to.

Likewise, if I got a couple of hits and I was gloating and running around and we lost or the team was losing, I’d get a talking to. [It was] this isn’t the way you carry yourself, you have to be in the game and you’re all in this together.

I think that kind of mindset stuck with me for the rest of my baseball career which was this isn’t about me, this is about us as a team, and what can I do to not only make the guys around me better but be a good person, teammate and leader in that clubhouse.

MMO: One thing I took away from the early part of your book was that you used wooden bats at times instead of aluminum because you were a bigger kid. Do you think that gave you an advantage at a young age and helped develop your approach at the plate?

Wright: That’s a great question and you’re very kind with that: I was pretty chunky. More round than heavy. [Laughs.]

I think it taught me a couple of things. One was taking care of yourself physically. Number two is I was lucky where my parents would do everything in their power to send me to different baseball camps, and financially that can be quite expensive, especially with a police officer and mother that worked in the school system. But they did everything they could to get me the best instruction that the area had to offer, and believe it or not that area is a hotbed for baseball and pretty good baseball instruction.

At a young age, I had some instructors that put wooden bats in hands, and this was a foreign concept to me because everyone else was using aluminum bats. And they were going a lot further and they were hitting a lot harder, but the instructors that I was seeing were saying, “This is going to make you a better hitter.”

I certainly think that using the heavier wooden bat allowed me to utilize the right side of the baseball field, hitting the ball the other way better than if I had just used aluminum through my upbringing. Maybe it was because the bat was a little heavier and I couldn’t quite get it around as fast forced me to keep my hands inside and shoot it the other way.

I think it definitely made me a better hitter at the time practicing and even in some games using wooden bats at a relatively young age at the advice of some of the instructors that I had.

MMO: A player you give a ton of credit to for taking you under their wing was super-utility man Joe McEwing. What made McEwing such a valuable ally for you in the beginnings of your major league career?

Wright: I got lucky where in the minor leagues I was roommates for a few years with Matt Galante. His father happened to be our third base coach in the big leagues, Matt Galante Sr.

I was roommates with Matt Jr. for years in the minor leagues and we played in Port St. Lucie in High-A ball. If we got an off day and the Mets happened to be playing down in Miami, we would take the trip down and his dad would put us up at the team hotel and take us out to dinner.

Matt Galante Sr. and Joe McEwing had a tremendous relationship, so Joe would tag along to some of those dinners. I got to know Joe when I was in the minor leagues and, fortunately, when I got called up, he immediately took me under his wing. Everything from I rented an apartment right next to his, teaching me directions like how to get to the ballpark, how to dress, what time to show up, and how to prepare for a game.

He told me I’d be pulled in all sorts of directions, but baseball is your number one priority. He taught me these lessons that stuck with me for the rest of my career.

He and his wife cooked dinner for me on a pretty regular basis. After my first game, I was exhausted, but he took me out to my first dinner in New York as a young player. He just seemed to be beyond a teammate, he was a friend or an older brother type. He really cared for me in a way that made me feel comfortable around some of those other veteran guys.

When I got called up, it was a very veteran team. I think being that comfortable, and Joe making me that comfortable, allowed me to have some of the success that I had early on.

MMO: From afar, you never seem fazed by the spotlight and media attention you received early on in your career. And as you developed, you basically became the Mets’ version of Derek Jeter in terms of being available and upfront with the media, along with doing the right things on and off the field. Did that come easy for you, and were there ever certain challenges you faced with how you wanted to be viewed and represented?

Wright: My father always said when someone asked him, because everyone thinks they have the next Derek Jeter as a son, or have the next Mike Trout, how did you get your son to be a first-round pick? How did you get your son to be a major leaguer? How did you get your son to be an All-Star?

And he said, “I never set out to raise a good baseball player, I set out to raise a good person.”

I was always nervous of when I spoke to the media, or the way I carried myself on and off the field, that I would somehow embarrass my family or somehow let down my mother and father, who raised me to be a specific type of person with the way that I carried myself. So that was always in the back of my mind of how would my three youngest brothers view me if I went out and did something stupid and embarrass myself? That was always in the back of my mind when I made decisions.

I had some great coaches along the way in the amateur levels, minor leagues and big leagues. I’ll never forget our minor league coordinator at the time, and he’s still with the Mets in a different role, Guy Conti. He always said, “You have choices, decisions and consequences.”

That stuck with me forever. To this day, I still think of choices, decisions and consequences, and that’s kind of the way that I’ve tried to treat my baseball career, and that’s kind of the way that I try to live my life away from baseball.

It sounds simple but it always stuck with me.

MMO: You write that “you’ll always remember the 2006 season as the year in which everything seemed to click.” What memories stand out to you about that season, and what made that club so special in your eyes?

Wright: For me, it was my first taste of the playoffs. But I think just the superstar talent [we had]. I mean, we had future Hall of Famers, we had perennial All-Stars, and you had a good mix of a veteran presence but also some young and up-and-coming guys that brought energy, especially the guy to my left in José Reyes.

I think it was a good mix and it taught me that I don’t think you can learn how to win until you actually practice it. It’s tough to sit there and talk about you have to have this winning mentality, you have to have this winning culture. You don’t know what that is until you win and you experience what that culture is like and practice winning, especially practice winning baseball.

I think that year I learned how fun it is to win, how exciting it is to win, how New York embraces winners and not necessarily great single-season performers. When I was a younger player in the minor leagues, and even when I got to the big leagues, I saw how the ’86 guys were embraced, everybody from the superstars of that team down to the 25th man on the roster. You say a name of a guy that was on that ’86 team and people raise a glass in the city and cheer them to this day. And that’s kind of what I wanted to be remembered as. I knew that at a young age that’s what I wanted to be remembered as.

Unfortunately, we didn’t make it all the way. But that’s the style of baseball that I wanted to play on a nightly basis was that style of winning baseball where you want your legacy to be not that he had some great years, but he played the game the right way and he played winning baseball.

MMO: A lot has been made about the original construction of Citi Field, and how it zapped you of some power. You write that you “could have – or should have – used Citi Field to your advantage,” and how the ’09 season exposed some holes in your offensive game. What did you have to do to mentally and physically adjust your game to play at the ballpark?

Wright: That’s a good question and it’s a fair question. I was accustomed to, by the time Citi Field was built at the end of the year, seeing a specific stat line and it’s a terrible way to think. But when you get out of that comfort zone and you see a weakness like I’m accustomed to hitting 25-30 home runs a year, then all of a sudden you hit less than half of that, it shocked my system a little bit.

And it was like, I need to get back to being that type of hitter; this team needs me to be that type of hitter.

Instead of doing what I should’ve done [which was] thinking the homers will come but let’s be a more complete hitter. Instead of hitting .300 or .310 or .320, I can use this to my advantage to hit .330, .340.

One of my strengths was going the other way, utilize those gaps and utilize all that room in the outfield for more base hits, take what the pitcher gives you. All of those clichés that you hear hitters say. Instead, for whatever reason, it was I’ve got to hit more homers.

I think that I got out of my comfort zone in trying to hit more homers, and it cost me being the complete hitter that I was, and that I still was after that. For that next year, yes, I hit more homers, but I struck out a lot more and I didn’t feel like I was that complete hitter that I was before I started making some of those adjustments.

Hindsight’s 20/20, but I wish that I could go back and say, forget the home runs, be the hitter that you are, and let’s utilize this as an advantage.

MMO: The Matt Cain hit-by-pitch on August 15, 2009, is a date I’m sure you’d like to forget. But what I found to be interesting is that you enlisted Howard Johnson to help regain your mechanics at the plate. What did you and HoJo work on to get your confidence back?

Wright: I think that every player – you’re not afraid of getting hit by the ball – but you accept the reality that there’s going to be times that you get hit, and hopefully it’s in a spot that’s an ideal spot to get hit if there is such a thing. But for me, it was kind of the first time that I took a direct hit to my head. It shook me for a little bit; I think it would shake a lot of people.

It wasn’t this thing where I got back in the box afterwards and I was scared, that wasn’t the case. I think it was just this natural reaction that I had to overcome this, hey, look, this was a hopefully once in a lifetime type ordeal, and just relax and think about hitting instead of thinking about the mechanics of hitting and how to get back on the horse after you’ve been knocked off.

I never felt scared, it was more of I couldn’t get back to the feeling that I felt before getting hit. It should be easy, like riding a bike, but I found it incredibly difficult to learn how to pedal again afterwards for a couple of months.

The thing that kind of got me over it was getting hit again, not in the head, but I got hit with a pitch after that and it was like, that was no big deal. I went to first base and all of a sudden I got comfortable.

It was just one of those weird things where I wasn’t consciously scared or nervous or anything, it was more just like I couldn’t get comfortable in the box again for a little bit after that. That was probably the best thing for me afterwards was getting hit by another pitch and kind of telling yourself that this wasn’t bad at all.

MMO: You write in the book that people ask you about having any regrets from your baseball career, and you admit that of course there are a few smalls things you would’ve done differently. But the one that stands out was the play at third with Carlos Lee on April 19, 2011. How often do you think back to that moment, and at what point did you realize something wasn’t right physically?

Wright: Going through all of my back rehab and all of my back issues the last couple of years, I thought about it a lot. [Laughs.] I think it’s just one of those things that it was a freak play, it was so out of the ordinary that it’s just I’d like to think that I tried to play the game hard and if that same play were to happen and if I didn’t have the hindsight of what I know now, I’d probably do the same thing.

It’s a foot race to the bag, and we dove at the same time. I just happened to jam my shoulder and my neck into the ground at a weird angle, which fractured a vertebrae. I definitely didn’t know it at the time that I hurt something but I didn’t know it at the time that it would ultimately really kill my back years down the road.

It was just one of those plays that, do I wish I would’ve let up and allowed him to take third? Do I wish I were a little faster where I could just beat him there and not have to dive? Of course! But it wasn’t the case and I tried to play every out like it was the most important out ever.

It was one of those freak accidents and freak plays that, do I think about it a lot? Of course. Is there anything I can do to go back and change it? Of course not. It’s one of those it is what it is types of things where I wouldn’t call it a regret, but I used to think about it fairly often.

MMO: Dr. Altchek gave you the news about your spinal stenosis diagnosis in 2015. What was your initial reaction upon hearing that, and can you describe some of the rehab and stretching you had to do each day?

Wright: The rehab I do on a daily basis to this day, I’ll do it for the rest of my life. It’s a routine that kind of strengthens the area and gives me the best chance of not being in pain on a consistent basis.

I’d say the initial reaction was kind of in shock and where you hang your head and feel sorry for yourself for a couple of days afterward. And I was no different. I mean, when you look at the diagnosis and the outcome, it’s not very positive for anybody, much less somebody that’s supposed to be in their prime in baseball.

After I got over that initial shock and moping around for a few days, it became my goal to kind of prove that wrong and get over that mental hurdle of kind of feeling sorry for yourself and saying, ‘You know what? It is what it is. It’s a bad break but I’m going to make it back on this field. I’m going to prove everybody wrong and I’m going to help this team win.’

That was kind of my mindset, and it helped that the team was having a good year. Every night I sat and watched the team after two rehab sessions and the monotony of going through my back exercises twice a day and rehab another time of day, it became evident that these September games were going to mean something in 2015. That gave me a ton of extra motivation.

The guys on that team were in constant communication whether it was through FaceTime or phone calls on the team bus or before and after games. That kept me feeling like I was a part of the team.

But certainly devastating is a good word to use when I got the news. My mantra for the rest of my career was, ‘I’m not going to allow this to define me.’ Ultimately, it would be one of the main factors that ended my career. But mentally, it was always that, when I look back on my career, it’s not going to be an I feel sorry for myself because I got hurt. It’s going to be I did everything in my power to overcome this and as much as I can go out on my own terms.

MMO: Where does your home run in Game 3 of the 2015 World Series rank in your career?

Wright: There’s not even a close second. Playing in the World Series, in New York, for that organization, in front of those fans was … a dream come true gets thrown around pretty often, but it really was.

I remember growing up in Virginia and our family were Mets fans because of our Triple-A affiliate in Norfolk. And standing in the backyard with my dad and my grandfather and Game 7 of the World Series – I know we didn’t make it to Game 7 – but [the] New York Mets are up to bat and here comes shortstop David Wright, at the time I played shortstop, albeit a little pudgy shortstop. Here comes the 3-2 pitch, whack, home run!

To be able to live out that dream in New York, for the team that I grew up rooting for, the team that drafted and developed me [was a dream come true]. It was one of the few times where I was rounding the bases and looking up at the stands allowed me to kind of soak it in and enjoy the moment, because of, selfishly and personally, all the hard work that I had put in to get back on the field. Those months of rehab and getting up at the crack of dawn to do one rehab session followed by another physical therapy session, followed by having to do back exercises on my own; you think about all of these things as you’re rounding the bases.

You felt like you accomplished the goal of not only getting back but making an impact and, obviously, being a small part of the team going to the World Series was a lifelong goal. I just wish we could’ve finished it off and became champions.

MMO: You write that during the 2018 season, you weren’t always honest with the Mets about how you were feeling, and that had they known more they would’ve shut you down. At what point during your rehab did you come to the conclusion that your body just couldn’t handle the grind anymore?

Wright: For me, it was fairly evident. I’ve always loved the game. I’ve always loved playing the game, practicing the game, even the most boring drills I always found enjoyable in a weird way because I was getting the chance to play baseball because that’s what I loved to do.

When it became tedious and painful and just trying to get through [it] without aggravating an injury; I remember playing in some of my first rehab games and just hoping and praying that they didn’t hit the ball to me. Just hoping that the pitcher would throw a fast, quick game and I wouldn’t be on my feet for very long at third base. Rooting for just trying to make simple contact at the plate so that I didn’t swing and miss or check swing and really hurt something.

It just became that you can’t play the game that way. Physically, it was one of those things where I was always fighting mentally that you can do this, you’ve got this and you’ll overcome this. But then physically it’s like no you don’t, and you can’t go on doing this.

It took a while for my mind and my body to match up, but once I was honest with myself it became pretty clear that physically I couldn’t do it.

MMO: I was fortunate enough to attend your last major league game on September 29, 2018, and it felt like a playoff atmosphere. What was the overall day like for you?

Wright: It’s emotional to even think about. I sat down and I kind of asked that I’d like to wear the uniform one more time, that I’d like to play in front of my kids and like to properly say goodbye to the organization and the fans. I knew it was a big ask because I hadn’t played in a while, and I knew there would be some hurdles that we had to jump. But when I got the go-ahead, I didn’t know what to expect.

I knew that it would be a big deal for me personally, because I had been a Met for over half my life, so it was going to be an emotional day for me. I didn’t know how the city or the fans would deal with it. I showed up to the ballpark at my usual time – around noon – and there were dozens of fans already waiting. When I went out and shook some hands, took some pictures, and signed some autographs, I was overwhelmed and shocked by the support of that night.

When I ran out onto the field for the first time and saw that it was sold out, just the signs and the thank-you’s, I kept telling myself that it should be the opposite and I should be thanking the fans. They’ve seen me fail way more than they’ve seen me succeed. For them to come out in full force and thank me for an injury-shortened career where no World Series titles to show for it, a handful of playoff berths, and a National League pennant, it meant the world to me to have that kind of send-off and support.

Every athlete wants to kind of write their last chapter and I certainly didn’t get the opportunity to do that. But for one day to have that emotional send-off really meant the world to me. That’s why I love New York so much and this organization so much, because of that bond from a relatively young age of just connecting with the city and fans. I think that’s the type of relationship that I think every player dreams of having with their city and their fans and I was lucky enough to have that.

MMO: And you know New Yorkers will never let Peter O’Brien hear the end of it.

Wright: [Laughs.] And that’s what makes New York so great is that I hate that for him, but it was so cool. I appreciated it.

MMO: When you look back over your career, David, what are you most proud of?

Wright: I would say a couple of things. One was being viewed as a leader and, ultimately, becoming a captain of that franchise. That’s probably my greatest personal achievement was that my teammates, front office, and ownership viewed me as a captain-type leader in the clubhouse.

More broad, although I would’ve liked to have played injury-free in my last few years, I’d like to think that when I put my head on my pillow at night that I maximized my potential. That a six-foot, two-hundred-pound kid from Southeast Virginia, who wasn’t the most talented player out there, genuinely felt like when I took the field every night I was the hardest worker out there and I was the most prepared. For that night, my mindset was to be the best player out on this field, and that didn’t matter if Derek Jeter was across the diamond, or Barry Bonds, or Mike Trout. It didn’t matter who, I felt like I was more prepared and worked harder than everyone else, and for that reason, I was going to be the best player on the field.

I’d like to think that I reached my full potential as a baseball player given the abilities that I had. But more importantly, that I was viewed as a leader and a good teammate and, ultimately, became the captain of this great franchise.

MMO: Thank you so much for your time, David. It was an honor speaking with you.

Wright: Awesome, Mat. I appreciate the kind words. Thanks again.

Purchase David’s memoir, “The Captain,” here.