In “For Love of the Game,” the 1999 sports drama starring Kevin Costner as an aging former ace, a line from Vin Scully (who appears in the film as a broadcaster) sums up what many pitchers often feel on the bump.

“He (Billy Chapel) will make the fateful walk to the loneliest spot in the world: the pitching mound.”

Standing on the mound can be an isolating feeling, especially when pitchers are struggling. For many, visualization and mental training cues can aid in trying to re-center and calm the nerves in front of tens of thousands of screaming fans. The mental side of the game is a crucial element that aids in the success of the individual player and organization overall.

However, the destigmatization of mental health in Major League Baseball is more of a modern approach, with organizations offering at least one Employee Assistance Professional (EAP), adding the option for mental health IL stints, many employing mental skills coaches and offering direct access to mental health resources through MLB’s wellness program.

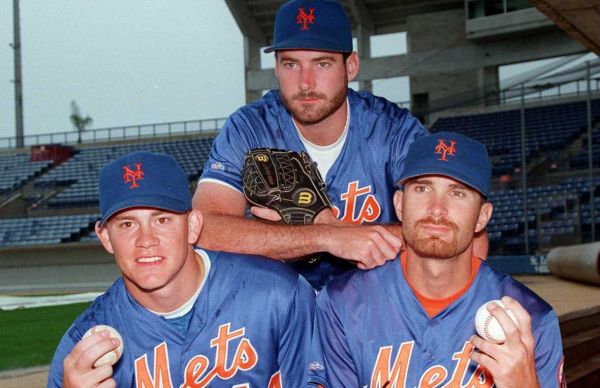

Bill Pulsipher, the former left-handed pitching prospect for the Mets who was part of the highly touted trio of Jason Isringhausen and Paul Wilson, dubbed “Generation K,” can be viewed as one of the pioneers in addressing the importance of mental health.

Pulsipher was selected by the Mets in the second round of the 1991 Draft (the 66th overall pick) as a seventeen-year-old out of Fairfax High School in Virginia. Over his first three minor league seasons from 1992 through 1994, Pulsipher tossed 435.2 innings with a 2.81 ERA. In 1995, Pulsipher split time between Triple-A and the majors, throwing a combined 218.1 innings in his age-21 season.

Making 17 starts in the majors in 1995, posting a 3.98 ERA and 1.6 fWAR, Pulsipher thought this was the start of his ascension towards the career he had always envisioned.

Unfortunately, Pulsipher’s professional and personal career took a turn in 1996, as the imposing lefty underwent Tommy John surgery and missed the entire season.

While working his way back to the mound, Pulsipher knew something was awry. Instead of the normal butterflies he’d regularly experience at the start of a game, Pulsipher was now dealing with extreme anxiety which turned into bouts of depression.

The game, which Pulsipher adored and reveled in the competition, had become a hardship.

“In a place where you feel like you shine and love being out there and putting on a show where you’re a showman as much as you are an athlete and competitor, I relished in that,” Pulsipher said while speaking over the phone. “To become the most uncomfortable place was very difficult.”

To his credit, Pulsipher continued to work through his struggles and played professionally for 19 years across the globe, including stints in Mexico, Puerto Rico, Venezuela and Taiwan. He’s been an outspoken advocate about the importance of mental health, and having the right outlets and resources to aid in treatment.

On May 6 of this year, Pulsipher threw out the ceremonial first pitch at Citi Field prior to the contest between the Colorado Rockies and Mets, as the club held a Mental Health Awareness Day.

Pulsipher’s appearance that day — during Mental Health Awareness Month — is a reminder that help is available and that the old stigmas regarding mental health should be kept long in the past.

I had the privilege of speaking to Pulsipher in June, where he discussed his early success in the minors, Generation K and how he dealt with anxiety and depression throughout his career.

MMO: Who were some of your favorite players growing up?

Pulsipher: I grew up a Mets fan. Doc Gooden and Darryl Strawberry were some of my favorite players with the ’86 Mets being my favorite team of all time.

I was a big baseball fan and I had TBS, so obviously Dale Murphy and Bob Horner [were others].

MMO: I read that your father was in the military and that growing up you lived all over the United States and in Germany. What was it like to relocate so often?

Pulsipher: I was a kid so I didn’t really think it was anything abnormal. It was one of those things where it was just what life was.

I think it actually helped me out because you get to see different places, meet different people, be around different areas of the world and have to integrate yourself. I think it was something that helped me in my maturation.

MMO: At what point during your development did you start focusing primarily on pitching?

Pulsipher: Not until I signed professionally. I didn’t grow up in the days of pitcher only. I gravitated towards basketball and baseball at an early age and I was a successful baseball player growing up; I would play first base, centerfield and pitched.

It wasn’t until I got drafted out of high school that I focused solely on pitching. I grew up playing all over the field but I was left-handed, so obviously the positions were limited.

MMO: What memories do you have from the 1991 Draft?

Pulsipher: Being called out of history class to be told I was drafted. They didn’t have a television show or anything like that and it happened in the middle of the day at the time.

Every outing in high school that year in the spring was full of scouts behind home plate with their radar guns and in the bullpen prior to the game. So it was obviously very exciting.

We had a good team, we had a very good team, that kind of fell short of expectations. As a senior, I had quite a few friends that were seniors that year too, so it was an exciting time for all of us to be getting closer to graduating high school and finishing our journey as high school baseball players. To have the Major League scouts around made for a very exciting time.

MMO: You got off to a phenomenal start to your professional career, and at a very young age. What were those early minor league seasons like for you, and how did you deal with that early success?

Pulsipher: It was a lot of fun and was everything I expected out of life. It was kind of what I planned for myself to be doing, and I thought that I would always be that way.

We won a lot except for my first year in Pittsfield (the Mets’ former Short-Season A club) where we went .500. It was strange for me to play on a team that felt like we were losing all the time because I’d always been on teams where we were relatively successful coming through high school and Babe Ruth and American Legion Baseball. That was a little different to see what playing .500 [baseball] was like.

Following that, I went to the South Atlantic League for a brief stint in my second year in pro ball before I got called up to the Florida State League, which at the time was High-A ball. We lost in the League Championship to the Clearwater Phillies; we were right on the doorstep of winning a championship.

The following year, we won the Eastern League in Double-A, and then in Triple-A it was kind of the same group coming up.

A lot of winning, a lot of fun, a lot of success and some of the greatest times in my life.

MMO: Times have changed and organizations have altered how they build up young pitchers’ workloads. You threw over 200 innings in back-to-back years in 1994 and 1995 (age 20 and 21 seasons). Can you talk about the development plan the Mets set out for you and your overall workload?

Pulsipher: I think you look back during that time when I was growing up and it was kind of the end of an older school and beginning of a new school era.

They always said that the number they used for pitchers to be Major League ready was 500 innings pitched in the minor leagues. I think that between the Mets having some struggles at the big league level and having some young pitching prospects, they probably wanted to get to that 500 inning mark as soon as possible to try and show that you were ready to go to the big leagues.

Looking back, a bad outing would still be seven innings giving up four runs, so you still threw 105-115 pitches. There weren’t many times you got knocked out in the second or third inning coming through the minors.

I think we all look back on it and my career wasn’t what I would’ve wanted or probably a lot of people wanted. I think that the way baseball and pitchers are used nowadays has a lot to do with me.

MMO: Since pitch count data started being tracked in 1988, only three pitchers threw 130 or more pitches in their major league debuts: Tim Wakefield (1992), John Dettmer (1994) and yourself (1995). I have a feeling we’ll never see those kinds of pitch counts again in a game, let alone a major league debut!

Pulsipher: No, and you’ll never see 200 innings in a minor league season ever again either.

MMO: Do you remember when you first heard of the ‘Generation K’ moniker?

Pulsipher: I don’t remember exactly. It was just one of those things, I guess. I don’t even know where it came from. It was a play off Gen X, we were Gen X kids, but I don’t know where it came from.

Generation K 1.0 – Jason Isringhausen, Paul Wilson, Bill Pulsipher

It was more of a media thing I would say. We wouldn’t go around telling people we were Gen K or anything. I think we were all focused on becoming Major League Baseball players and being successful.

MMO: You missed the entire 1996 season with Tommy John surgery. When did you first notice that something was not right with your elbow? During an interview you gave with Sweeny Murti, you said you were never the same after the surgery. Can you elaborate?

Pulsipher: I did have a little bit of shoulder inflammation in 1994. I don’t think I even missed a start, they might’ve just pushed me back a couple of days and I took some anti-inflammatories.

The first time I really noticed something was wrong was when I had a start in Montreal against Pedro Martínez [near the end of the 1995 season]. He threw a shutout that night I believe. Two days later was my bullpen day and I was doing my pen in Montreal and something just didn’t feel right in my elbow. I never felt anything like that before. That’s when they sent me back to New York to get an MRI and I was told I had a sprained ligament.

At the time I was like, I’ve sprained my ankle numerous times, I’m all right. What’s the big deal? I was prescribed rehab and told that I’d be all right. I rehabbed in Port St. Lucie and I was there six days a week. I came into spring training and went to see the doctor again and they told me I was fine and it’s like nothing ever happened.

I didn’t make it out of spring and I needed to have Tommy John. I remember pitching against the Expos again, believe it or not, on a televised game in spring training, and I remember warming up in the pen thinking I had never felt so good in my life. In the second inning I threw a curveball and I felt something and it was actually a very good curveball for strike three to end an inning. Walking off I just remember giving the throat cut sign that that’s it and I know something is wrong.

Lo and behold you get an MRI and they tell you that there’s too much inflammation and they can’t determine what’s going on. Then the Mets traded for Mark Clark and a week later I’m told that I need to have Tommy John. I don’t believe that they didn’t know what was going on the week that the first MRI happened.

I had a curveball coming up that was never the same. I was also told that the way I threw was the reason I got hurt. I kind of threw the ball like Andy Pettitte. I threw hard, I threw 92-94 miles-per-hour and I had a really, really good curveball and when I came back my curveball was just not quite the same.

Because they decided that the way I threw was the reason I got injured, they wanted to turn me into a sinkerball pitcher and try to start moving the ball less. That just wasn’t the way I naturally wanted to throw the ball.

That confused everything and I think it was a terrible decision by everybody as a whole to try and do that. My idea was I had pitched that way from the time I was eight to twenty-one, so if I can pitch that way for another ten years and then the elbow blows out again, who gives a shit?

I think that changed everything to try and learn to be a two-seam/sinkerball guy. That just wasn’t my thing.

MMO: Was that when the anxiety and depression started?

Pulsipher: No, it wasn’t until after. I was starting to come back and be right where I was and I totally believed in myself. I lived in Port St. Lucie and worked out with the pitching coach who lived there. I worked out six days a week and there was no talk of anything other than getting healthy and have a good spring.

I pick up the newspaper one day and it said I was going to go on a rehab assignment to start the season. I’m like, wait a minute, why haven’t we discussed any of this at all? I guess when you’re 22 in that day and age they don’t feel like they have to tell you anything.

I had a good spring training, but I just wasn’t throwing quite as hard. But zeroes are zeroes and outs are outs. I went on the rehab assignment and the first outing up in Syracuse was really cold and something wasn’t right. I’ve always had some butterflies with the first batter of the game or first inning until you get into it.

It was one of those things where it was there and it was constant and it was impossible to play and be successful when you’re dealing with extreme anxiety.

MMO: And then from there it got progressively worse?

Pulsipher: Yeah. You’re going out there every five days trying to get outs and nobody understands what’s going on because they didn’t want to understand what was going on back then. You don’t understand what’s going on and thinking why in the world am I feeling like this.

I was a few starts into my rehab assignment when I told them, ‘I have no business being on the mound right now. Something’s not right.’ Their idea was to take me off the rehab assignment and send me down to A-ball where I was still playing with guys that were either my age or some even older. For them it was, let’s put him down at a lower level and he’ll be all right.

There was no rhyme or reason for me to be out competing on the field. We needed to figure out what was going on.

MMO: Was that when you started to work with the team psychiatrist, Dr. Alan Lans?

Pulsipher: We had contact while I was coming up through the minor leagues. I was a bit of a wild child and he was the guy who tried and talk to the guys that might have been a little different than the others. So me and him had a relationship prior to that.

That was when we first started trying to figure out the anxiety. At first it was like, I’m obsessive compulsive. I just think it boiled down to social anxiety disorder and some anxiety which obviously leads to depression when things aren’t going your way.

MMO: Did you ever work with Harvey Dorfman (renowned mental training consultant)?

Pulsipher: No. I know of his books and of his work, but I never worked with him personally.

MMO: How did you manage the anxiety and depression?

Pulsipher: I had to take some medication. That changed over the years and doses changed over time. I was never one-hundred percent good at sticking to things, so there would be highs and lows.

You’d be going well and then go back and forth and self-medicate. I think you’d be surprised how many guys are probably using some form of medication one way or another in this day and age in the game.

MMO: Outside of the United States, did you have a favorite country that you played baseball in?

Pulsipher: It’s tough to say. I made the most of wherever I went. Taiwan was great and I loved playing in Puerto Rico. I played there about nine times during winter ball. Not to toot my horn but I think I became a bit of a living legend down there because I played there so much and had some success.

MMO: Have you ever thought about getting back into the game in some capacity?

Pulsipher: I would love to but financially it wouldn’t pay off. They’re not looking to pay enough money for me to be able to make a living being a low-level person.

I had a reputation as a younger player that I’ve had to try and outlive. I was a little bit of a wild child, or back then they’d say crazy. I was just way ahead of my time. If you look at the way players are allowed to act and things that go on nowadays, I’m sitting at home as a 49-year-old yelling at the TV about what goes on. [Laughs.] I was just way ahead of my time.

MMO: What are your thoughts on the way Major League Baseball has evolved in the sense of providing outlets and changing some of the stigmas on mental health?

Pulsipher: I think they’re doing a good job. You look at the Colorado Rockies, they had a couple of guys and in the beginning of the year there were several guys who were on the IL and they weren’t trying to make up a reason for an injury. It was basically for mental health issues.

The game is hard, man, the game is super duper hard. When you watch it on TV, everybody makes it look really easy. Everybody has played baseball at some point in their life, and the further away you get from your playing days, and this goes for everybody including former major league players, you remember yourself being better than you really were a lot of times. And that goes for the average fan who thinks baseball is easy.

Baseball has come a long way. I think they’re realizing the difficulties that the players go through and pressure they put on themselves, by the organization and fans is: we are human beings. There are human being things that happen to the guys you watch on television. I think MLB is doing a better job.

I think if you were to go off and say that you were going to take a nap in the clubhouse 25 years ago, they would think you were out of your freaking mind. Now, they have sleep deprivation rooms, so obviously the game has changed.

MMO: What did it mean for you to throw out the first pitch at Citi Field on Mental Health Awareness Day this year?

Pulsipher: It was really cool. I was a little apprehensive about doing it because I wasn’t sure how I’d be perceived relative to some of the things we just talked about. I’ve always been pretty well received by Mets fans, regardless of outcomes of my career or anything like that.

I was one of the first guys that really said something so it kind of made sense to have me involved, and it was an honor to go back out there. It wasn’t walking back onto the Shea Stadium mound but it was my first time being on that field for quite a long time.

It was such a special moment for me and hopefully people who saw it enjoyed it as well.

MMO: What have you been up to since you retired from playing?

Pulsipher: I work road construction (on Long Island) and I give pitching lessons at 365 Athletics in Bellport. I’m just a regular, old dude.

MMO: When you look back on your career, what are you most proud of?

Pulsipher: That I will always be less than a one-percenter and nobody can ever take that away from me. I did it, I made it, I stuck it out and I never quit.

I got to play for twenty years and at the highest level on the planet. Nobody can ever take that away from me.