As all 30 Major League Baseball teams continue to seek an edge in the sport, hoping to identify any and all resources to improve their team’s chances of winning, an avenue where there has been further acceptance is on the mental side. Mental skills coaches are employed by 27 of the 30 major league clubs to open the 2018 season, a record for the sport.

For decades, players who would seek counsel and were seen talking to sports psychologists were viewed as “weak” to the old school players, an unfortunate stigma that couldn’t be further from the truth.

The role of a mental skills coach is to help train the athlete’s mind to better perform and relax in the most crucial and intense moments of the game. Mental training techniques such as proper breathing, self-talk, visualization and physical triggers are some of the components used in aiding and reminding a player of what they already know: you’re good enough to be here.

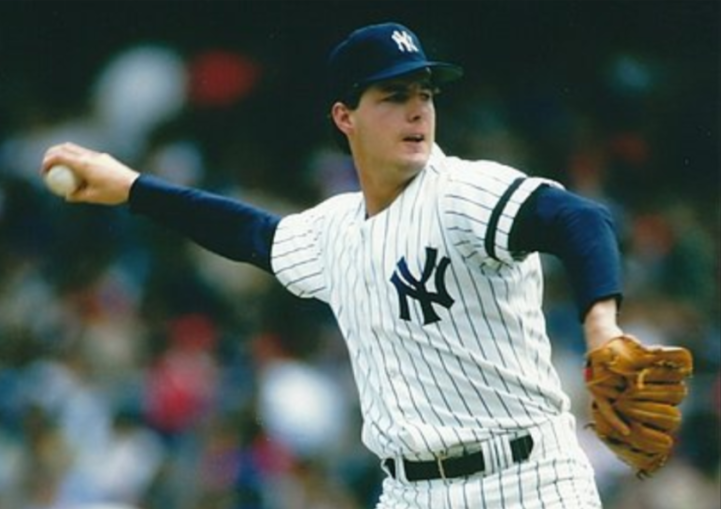

Thirteen-year major league pitcher Bob Tewksbury, not only utilized these techniques during his own playing career — one that consisted of playing for six different organizations and making the All-Star team in ’92 — but now implements them as the San Francisco Giants’ mental skills coach.

Tewksbury, 57, signed with the Giants in the winter of ’16, after spending 11 seasons in a similar role with the Boston Red Sox. After his playing career was through, Tewksbury went back to school, earning his Master’s Degree in psychology from Boston University and receiving mentoring from renowned mental skills coach, Harvey Dorfman.

Tewksbury, along with his co-writer, national baseball columnist for Bleacher Report, Scott Miller, penned a book released this March that brings to light the work and techniques used for players interested in strengthening their mental side of the game called, Ninety Percent Mental: An All-Star Player Turned Mental Skills Coach Reveals the Hidden Game of Baseball.

He recounts personal conversations and interactions with several of his clients, including Andrew Miller, Jon Lester, Anthony Rizzo and Rich Hill, detailing the mental work they put into each performance, just as they would on drills like taking batting practice or throwing a bullpen. He also explores revelations from his own career, along with crediting those who helped shape his path.

The value of having a mental skills coach on a team’s payroll is essential and of great benefit, as it gives players another avenue to seek guidance if their game is off. Often times fans rashly jump to conclusions as to why their favorite player is in a massive slump or seems out of sorts on the diamond. Exploring what the player is dealing with mentally, and being able to understand how to correct mental lapses and rewire thoughts is a skill set that will only continue to gain more prominence in the game.

As Cleveland Indians manager Terry Francona – with whom Tewksbury worked closely with during his time in Boston – says in his book, “We work our fielding, our throwing, and our hitting. But the mental side might be the most important tool. If you view it as a weakness, that’s silly. It’s like, you can do better. So we’re trying. If you don’t, you’re kind of missing the boat. There are ways to get better.”

This tool, as Francona describes, is just as crucial as being in pique physical shape. Having a player arrive to the park not just physically prepared, but mentally sharp gives the team a better chance of having the player perform well.

A major advantage Tewksbury has beyond his degree in psychology is the fact that he played in the majors for thirteen seasons, which can help players he works with feel a bit more comfortable. He compiled a lifetime record of 110-102, with a 3.92 ERA over 1,800 innings pitched. His lifetime walks-per-nine mark of 1.45 is the second-lowest mark among starters with at least 1,500 innings pitched since 1920.

He made his lone All-Star team in ’92 while with the St. Louis Cardinals, posting a 16-5 record, leading the National League in win/loss percentage (.762) and the majors in walks-per-nine-innings (0.773). He finished third that year in N.L. Cy Young voting, behind Greg Maddux and Tom Glavine.

Being able to speak not only in terms of psychology but to understand the nuances of the sport helps to give Tewksbury a further advantage when speaking to players; perhaps giving the players less pause when wondering if they should speak out or not for guidance.

Though, as Tewksbury notes in his book, Harvey Dorfman warned him that his pitching career would be both a blessing and curse when it came to his second career as a mental skills coach: “The blessing was that it would open doors and I would have instant credibility. The curse? I would need to think as a mental skills coach and not as a former player when working with a player. Because of my pitching experiences, it would be easy for me to give advice or counsel as a former player. The challenge would be to not look at things that way but from the view of a mental skills practitioner.”

I had the privilege of speaking with Tewksbury for Mets Merized, where we discussed his day-to-day routine as a mental skills coach, how receptive players are towards it and look back on his thirteen-year major league career.

MMO: What prompted you to write the book, and what was the process like for you?

Tewksbury: It actually was the third attempt at this, and I wasn’t sure what direction to go. The purpose was to write a book based on my experiences both as a player and a mental skills coach, but I wasn’t sure what the narrative was going to be or the format.

With the first writer I had, I written down a bunch of stuff from my career; I had journals that I kept from my playing days that helped me to remember stuff.

That just kind of died because I had no direction and he really wasn’t a writer, he was kind of an editor and I needed someone to pull me through. I put it away for a couple of years and then another agent that I was talking with I told the general theme about. She got interested and I found another writer that we wrote a proposal [for] but we couldn’t agree on the direction of the book, so that died down.

I get a call one night in December of 2015 I think it was, maybe 2016, of an agent that had heard wind of my wanting to do something. He had talked to a couple of people and his name is Rob Kirkpatrick, he worked at the Stuart Agency and I think it was in New York City. He said, “I really think there’s something here, I think we should talk about it.”

So we did and came up with a narrative and a great co-author in Scott Miller, and we were able to put it together. We think of it more as a mental performance book with a baseball narrative than a baseball/mental skills book.

That’s the way we were going to go and the feedback has been really good on it.

MMO: Early on in the book you mention a moment that seemed to quickly pique your interest in psychology when you met Og Mandino (author, The Greatest Salesman in the World) at a sporting goods store you were working at in New Hampshire during an offseason in the minors. Can you talk about that time in your life and how reading his book, along with others, helped sow the seeds for you in the mental side of the sport.

Tewksbury: I was a minor league player so I had to have a job in the offseason. I worked at this store called Mickey Finn’s, which was like a miniature Dick’s Sporting Goods. I worked there and I saw this fellow in the shoe department and I had never heard of this guy. I had read Norman Vincent Peale and The Power of Positive Thinking. I had never heard of Og Mandino, but I read his stuff and it just confirmed how important psychology and our thoughts are.

I kind of used it at that point in my career as best as I knew how, and I had success with it. St. Louis is where I really tried to apply most of it at work with benefits. He was just kind of – I wouldn’t say hugely impactful – I think it’s more of a fun story than it is anything else. But it definitely reiterated the importance of how important the mental part of performance is.

MMO: What does your day-to-day work life consist of with the San Francisco Giants as a mental skills coach?

Tewksbury: It’s very informal. I get to the ballpark with the medical staff, I’m on the road most of the time with them, not all the time but mostly. I get to the park really early with the medical staff and go through the meetings, then I’m kind of around.

I’ll check in with the coaches, there are no formal meetings. In spring training there’s a time where there are more formal meetings with the pitchers and the position players but once the season starts it’s pretty informal. Catching guys here or there, talking with the coaches; just kind of being a resource.

Occasionally that’ll lead to a one-off conversation or a player that might meet in his room to talk about something, but it’s very unstructured. The structure is it’s unstructured. (Laughs)

MMO: Have you found that many of the players are receptive to your line of work?

Tewksbury: Some players are. I think it’s kind of mainstream psychology, it’s not for everybody. Not everybody wants to go talk to a counselor or therapist, and that’s the same thing with the team.

One thing that is there is the players’ respect that I played the game and understand that. There are probably a handful of players that are somebody I can talk to that might be looking to implement it, so five out of twenty-five which is probably pretty normal.

Then there are a few that you don’t ever talk to but you know that they’re listening to stuff you say or the stuff that you do or talk about. Sometimes it happens when you don’t even know it’s happening.

MMO: You were a pitcher that relied on control and command of your pitches, rather than trying to play to the radar gun. One of my favorite stories from your book was when you talk about the eephus curveball you threw to Mark McGwire twice in the same game. Can you talk a little about that moment and the prep work you put into facing a lineup, including keeping a journal?

Tewksbury: The McGwire thing was he hit a home run off me the year before on an inside fastball. I had thrown that pitch [eephus] more my last year just because it was fun and it offset timing. I mean, it’s 46 miles-per-hour! It’s a pretty unique pitch and it wasn’t a lob pitch, it had forward spin on it, like a curveball.

I just threw it to him to see what would happen and he swung at it and grounded out and then popped up to the infield. But he was smiling about it and I sent him over a note after [the game]. He replied that he was a sucker for those and swung at them all the time, so it was really good fun.

My preparation was I knew I couldn’t just throw that to anybody, I had to throw it to people that I felt were mostly power hitters who couldn’t stay back and were really set on the fastball, even though I didn’t throw real fast. I wouldn’t throw it to just anybody, I picked my spots for it and I didn’t want to overexpose it.

My preparation always included – this is before analytics and scouting reports – some information from the advance scouts but our charts used to be our own spray charts that the pitchers did; where they hit the ball. And we would shade people certain ways but we didn’t shift, there was a difference.

I kept my own scouting reports on teams and players and used my own reports on mostly how to prepare for that any one lineup and who was hot, who was not, who you could throw the curveball to, who you couldn’t. All of that info goes into play when making a report.

MMO: You cite a mechanical adjustment that your pitching coach in St. Louis, Joe Coleman, made for you in 1990 by bringing your arm angle down to a three-quarters level delivery. Was that the adjustment that really enabled you to control the strike zone like you did for the rest of your career?

Tewksbury: I think it helped, Mathew. I always had pretty good control but I turned into having really good command. I think the reason I moved my arm down was because it hurt my shoulder.

Joe was really good at picking up when I’d start to get away from my hand, a little bit of my hand would get further away from my head, and keeping the elbow in a good spot. He was really helpful with that and just game reports and understanding that I was an old-young pitcher age-wise, I wasn’t young but experience-wise I was. He was a great asset to me at that time.

MMO: In Chapter Seven, you write about the role Joe Torre had in your career and your time in St. Louis. You write that Torre was as close to a mental skills coach as there was in 1991. What was it about Torre and his influence that made you bond so well?

Tewksbury: Joe was a great communicator and there’s a conversation [in the book] after I took myself out of the game where he said, “Look, I believe in you.”

I kind of talk about him giving me permission to be successful. I think you’re always wondering whether the manager likes you. if you’re doing good enough, and where you stand.

Joe communicated that which only built players up more. He certainly did that for me then, it was a very important time. The two of them [Coleman and Torre] were definitely beneficial to my career.

MMO: Three players that you write extensively about in the book are Anthony Rizzo, Jon Lester and Andrew Miller. Can you share a little on all three and what makes them so mentally tough?

Tewksbury: Yeah, they worked with me! (Laughs) First of all, they’re all really good people and they have good families, good backgrounds, and they’re people that I respect and fun to work with. I think that type of caring individual really respect what people do and is willing to work to try to get better and it wasn’t just yeah, I’ll do it once. It was I’ll do this and I’ll commit to it.

They’re very committed, very dedicated, very loyal to the people they know and work within their craft so it really made working with them easy.

Andrew is very intellectual. He had struggles, obviously, that are well documented as a number one pick. All of these guys just needed subtle reminders, it wasn’t a lot of in-depth, hour-long conversations. They were little quick five-ten minute reminders and they’re all very smart and they like to compete, all three of those guys, and Rich Hill, too. They like to compete and they have a little fire in the belly which makes them successful.

MMO: How do you go about understanding what techniques would work best for each individual player?

Tewksbury: That’s a good question, I think it kind of depends on the player. You do an intake and see where they’re at and what’s going on. Is it their thinking patterns? Is it a situation? Then you kind of fit it to all of those components you talk about: self-talk, breathing, imagery, visualization.

I talk about that with everybody because I know how powerful it is and how it works. Then it’s just a matter of when do they use the breathing? What type of visualization do they like? Then I’ll make an audio program specifically for them; some people like music, some people don’t. Some like to imagine seeing themselves from their own eyes versus seeing it on TV. There are lots of variables that come into play but those are the core components of what I do, for sure.

MMO: You write how baseball was one of the last sports to embrace mental health in the sport and the reluctance to it in various parts of its history. To you, where do you see baseball going in regards to the mental health/skills side? What more can and will teams do to ensure they’re giving their players access to every possible resource?

Tewksbury: I think it’s going to continue to grow because it’s in the collective bargaining agreement that teams have to provide this resource. Teams are staffing this resource at various levels much like they did strength and conditioning. I think there’s going to be three to four practitioners on every team throughout the system. There are going to be more Latin American, bilingual, sports psychology coaches or mental skills coaches.

I think with the advances in technology and the stuff that’s going on with all the brain waves, brain research, MRIs, I think there’s stuff that’s in the works now that I can’t even imagine that people may be able to use as a tool to help the players. So I think the field is going to continue to grow for sure.

MMO: Can you talk a bit about what Harvey Dorfman meant for you personally in your career?

Tewksbury: Harvey was great, mostly on my second career. He said I didn’t need to go back to college, that I could do this without going back, but I’m glad I did. He also said it would be a blessing and a curse, and he was right.

The blessing is that I know the game and I can talk the talk, but the curse is that I have a set of skills that isn’t one dimensional. From a former player’s perspective it’s multi-dimensional with my sports psych background, and sometimes I forget to do that. Sometimes I forget that I have to lean on that part, too.

He was a great mentor and I miss him. I used to run cases and situations by him and I can’t do that now. I miss him, I think the whole game misses him.

MMO: In Chapter Six, you detail how close you were to throwing a perfect game on August 17, 1990, against the Houston Astros. Afterward you touch on the difference between those who strive for perfection and those who refuse to accept anything less. Can you speak on that for your career, and how you try to impart that on players you work with today?

Tewksbury: I think we all like to do really well and to be liked, to not fail. But as Harvey [Dorfman] would say, “Do you know anyone that’s perfect?” And the answer is no. Then he would tell players, “Well, what makes you think you’re going to be the first one?”

I use that story as well with players. To strive for that is good, to expect it and not get it and have that wreck your day over and over is miserable, and that’s what can change. The results after the ball leaves the bat or the pitcher’s hand, there’s nothing the player can do about it except get ready for the next one. Players want to control the results, they want everything to be perfect. They want their well-hit balls to be hits, they want their little dunk hits to be hits, and pitchers want all the calls made by the umpire and all the plays to be made.

I’ve said there have only been 23 perfect games in the history of baseball, so there’s a good chance – as a pitcher – that something’s going to happen and you’re not going to be perfect and you’re going to have to deal with it. So continue to strive for excellence but understand if you fall short of that, that’s okay. It’s getting people to understand that you don’t have to feel perfect and don’t have to play perfect in order to perform well.

MMO: You begin and end your book with the act of breathing. You mention that proper breathing can reduce blood pressure, improve sleep, maintain health, sharpen focus, and improve performance. It’s such a simple concept, yet I’m curious in your line of work, how often do you have to almost reteach the proper ways to breathe, and get guys to buy into this concept?

Tewksbury: A lot! Yeah, that’s a great point. A lot because players forget, they take it for granted and they don’t understand that they try to think their way through and you can’t think yourself to relax, you have to breathe to relax. If you lay down and close your eyes and say, “I’m going to relax, relax relax,” you’ll never relax. But if you close your eyes and say, “Breathe,” your body settles down.

Reminding the players of that is a really big tool, it’s a very big asset for performance and it’s a constant reminder.

MMO: I appreciate your time today, Mr. Tewksbury. Thanks very much and good luck with the book.

Tewksbury: Thanks, Mathew. Take care.

Follow Tewksbury on Twitter, @bob_tewksbury

Purchase, Ninety Percent Mental: An All-Star Player Turned Mental Skills Coach Reveals the Hidden Game of Baseball, here.