This is part two of the interview, Jon Updike talked about Pete Alonso and Matthew Allan on Monday here.

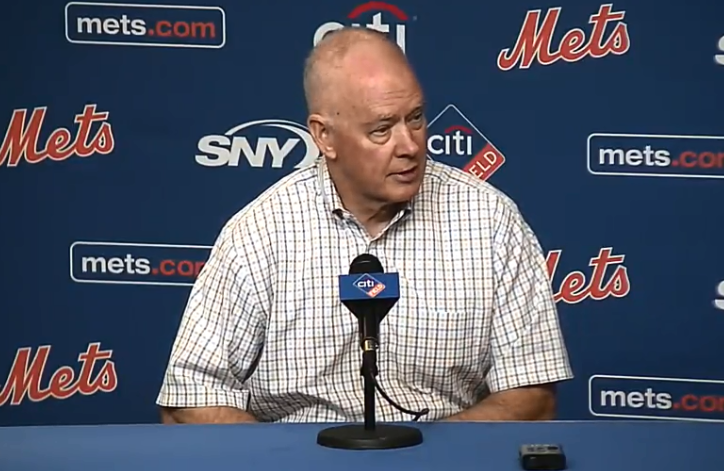

Former Mets’ area scouting supervisor Jon Updike believes in paying it forward.

As a former 28th-round pick by the Seattle Mariners in the 1993 MLB Draft, Updike reflects fondly on the scout, John Ramey, who took the chance on him as a reliever and offered Updike all he could ask for: an opportunity.

After his professional playing career was over, in which he spent time with the Mariners, Milwaukee Brewers and Texas Rangers organizations, Updike transitioned into a college baseball coach in Florida. The connections and relationships Updike built in Florida led him back to professional baseball, where the New York Mets hired him as their area scouting supervisor in North and Central Florida in 2014.

Updike’s new career offered him the chance to afford opportunities to young players, just as Ramey had done more than two decades prior for him.

The life of a scout includes logging a ton of miles on the road while traveling from game to game, building relationships with coaches, players and families, and doing extensive scouting work on why a particular player should merit an organization to sign him.

While scouting can often be a thankless job, remaining in the background while the talent they scouted and signed hopes to see their dreams imagined, Updike’s name was often mentioned throughout the 2019 season.

That’s because one of the players he signed back in 2016 burst onto the scene, surpassing Aaron Judge for the single-season rookie home run record while becoming the sixth Met to win Rookie of the Year: Pete Alonso.

Part of Updike’s job as a scout was to not only identify tools and projections, but to also assess a player’s work ethic and makeup. Those traits stood out for Updike when he was scouting Alonso, as he saw a player that not only had the talent but composure to handle the large media market that is New York.

In last year’s draft, Updike was responsible for signing Matt Allan out of Seminole High School in Sanford, Florida, in the third round. The right-handed pitcher was considered to be a potential first-round talent on many draft boards, but fell with concerns of his asking price along with his commitment to the University of Florida.

The Mets restructured their draft and were able to save money from their draft pool by signing college seniors in rounds four through ten for below-slot bonuses to help meet Allan’s demands.

This past November, SNY’s Andy Martino reported that Updike left the organization to begin his next chapter as President of Digital Scouting and Player Development Solutions for BaseballCloud, a software company that offers technical, data-driven solutions for players and clubs.

BaseballCloud digests in-game metrics from multiple technologies and accessories and is then presented in a way that’s easy to understand in order to track progress and areas for a player to work on.

BaseballCloud was designed for players and coaches as an easy-to-read development tool which allows users to store and track their data and progress. That tracking of progress is what Updike refers to as player mapping. The analysis BaseballCloud provides allows players and coaches to view their data with 3D visualizations and graphics that are easy to grasp and utilize for a player’s development.

The hope is that BaseballCloud allows for more impact on the development of amateur players; getting them more accustomed to the data and metrics while consistently tracking their progress using their revolutionary software.

Updike’s new occupation incorporates his extensive scouting background with analytics to provide custom visualization tools that transform how data is used at the amateur levels.

While he’s no longer affiliated with a specific Major League organization, Updike now has the chance to impact even more young athletes hoping for the chance to one day make it professionally.

He hopes the software will help propel amateur players to reach even more of their potentials while providing them with all he could ask for in his own professional playing career, and what he afforded to many players in the Mets organization: an opportunity.

I had the privilege of speaking with Updike this past December where he talked about his life as a scout and new role with BaseballCloud.

MMO: Can you talk about the scouting process in terms of building a relationship with the player and what you did to further identify whether he was someone worth signing? How would you build that rapport?

Updike: Through their practices and events you scout them at. You go over reports with them and then the players you target you start to do a deep dive on. You build a true relationship with the player to where you’re in their house. They finish a game and they come to you and ask you, not from a scouting perspective, is there something that you see that can help me? You build that type of relationship with the player because you become the trusted voice.

I think when you’re doing your job well is when you’ve got players that sign with other organizations and they still call you because they trust your opinion. What we had with Sandy Alderson and Paul DePodesta when they were with us, and everyone talk about the Moneyball model. Part of the Moneyball model was, at least the way I looked at it, this isn’t scouting. It’s player acquisition. You spend several years developing an idea of what a player is. Now we’ve decided that we’re going to spend more time and money to acquire this player.

Just think about it like a pie chart; a third of the player would be an area look, a third of the player would be the national look and a third of the player would be statistical analytics. That’s Moneyball. If I like the player and the national guys like the player, but maybe the analytics department doesn’t like him, if I’ve got two-thirds of the puzzle. I can override what the analytics guys say. If I like the guy and the analytics guys like him we can maybe override the national. Having two-thirds of the pie allows you to acquire the player, a beautiful model. It worked for a long time and was proven.

A few years ago, I noticed in our game and in the draft room how that changed. Another piece of the puzzle was added. It became a quarter area, a quarter national, a quarter statistical analytics – because even at the high school level we have much more robust, cleaner more accurate statistics – but the new piece that was added that didn’t exist was metrics. In-game metrics gathered from Trackman, Flightscope, swing sensors or biomechanical data.

We have that information and when you think about it, you’re making a purchase. You’ve got to have as much information as possible to allow ownership to say, yeah, let’s write the check. It just can’t be somebody’s gut. It can’t just be my opinion. It’s got to be a very large amount of information and we filter that down to one, two, three options. You choose the best available option that’s going to help you in the long run.

The beautiful thing about Matt Allan (Mets’ third-round pick in 2019) is and how everything really came together. Matt is an example of what the future is going to be at the collegiate level. We have a long history with the college player, usually two to three years of scouting on the high school end and then a minimum of three years at the collegiate level. We’ve got five or six year’s worth of traditional scouting work done on this kid. Now the national showcase tournaments, through larger scouting events, and even with private workouts, we’re able to gain data. We’re also able to have clean statistical analytics so now we’ve got a larger body of work from high school to college so that we can look for predictors and look for trends.

For a high school player like Matt, you don’t have as much. Matt was in a situation where he threw at a high school that had in-game capture. Every pitch that kid threw the entire season, there are metrics on. It makes the decision a lot easier; it’s like taking a knife to a gunfight.

Matt was an incredible player and Central Florida and the state of Florida is the epicenter of baseball. You have volume of scouts, you have volume of national decision-makers, you have multiple major league clubs that have facilities there. So in the traditional aspect of scouting, it was easy from that standpoint from the industry to just see him and scout him. But the additive part of it is the statistical analytic aspect, and the selling part was the metrics.

If you’ve got the complete pie for a player, even if their demands are higher from a financial standpoint, now you’re going apples to apples and that was really one of the first times that’s existed. That’s why Perfect Game All-American Classic, USA Baseball, East Coast Pro and Area Games are important events. It’s not just because they’re all in one spot and it’s easy to scout them. It’s because that’s where the metrics are. And traditionally, that would be the last time you got metrics on a player.

Our narrative at BaseballCloud, and what we’re finding out through our data scientists, is a player physically and skills-wise changes every ninety days. I want a collection of data by a player a minimum of every ninety days, that way I can create a fingerprint and a map for that player. It allows me to predict where this player will be in the future.

What we’re trying to do is implement that system into amateur baseball, so that there’s a way to be able to collect data. Analytics is the buzz, well guess what? Analytics has been here, we need volume of analytics, we need volume of people to run the machines. More technology, more problems, let’s put it that way.

The other part of it is you have to use the machines in order to figure out how to even apply the information. We’re at a great time in our game because of the growth of technology. But because a piece of technology exists doesn’t mean that the technology is going to be viable or provide answers. You have to vet it, trust it, understand it; what does this information mean?

Baseball has some really big challenges coming down the pipeline as technology grows in our game. It’s easy at the big league level; I can run regressions and I can do wonderful things. Baseball Savant is a beautiful tool and I love it. But I can’t do that at the amateur level because major league data is the cleanest data on the planet. It doesn’t exist in college really.

We make the assumptions that we have all the same data in college. Roughly ten percent of college baseball has clean data. At the amateur level and high school level, it’s bits and pieces. Think of it this way: the importance of the Cape Cod League. I love the Cape Code League and going there, it’s a tremendous piece of amateur baseball historically and for the players’ experience.

The true value of the Cape Cod League is there’s Trackman on every field. End of story. Let’s say there’s a player up there from a conference that doesn’t have in-game capture. When you go to the draft board, if that player doesn’t have metrics and some type of metrics, he’s not going to be selected. He’s not going to be selected in the first ten rounds.

What we recognized and understood is that the demands from the professional game are going to trickle down to the collegiate game. As we work with universities to help grow technologies, in-game capture, ways of digesting that and helping schools to create analytics departments and helping coaches adjust, even with my title of digital scouting, that’s what it’s going to become. It allows you to vet the players.

Major League clubs have budgets; a scouting department has a budget and it’s not super robust. Everybody has to work within parameters. At the collegiate level, and again, people will look at stories like Alabama football having helicopters and things like that, that doesn’t happen at the college level.

When I was a college coach, I had roughly $1,200 a year budgeted for recruiting, and that was coming out of my own pocket. That’s the reality. Social media and using technology to be able to identify players, see metrics and vet players allows you to target and not have a huge budget. It allows you to spend your money more wisely, and that’s really what it’s all about. It’s not really about trying to make the game smarter, it’s about making better decisions and save money.

Our products provide a solution that allows users to absorb information and apply it to their teams from a development standpoint. In Major League Baseball, the analytics are there first for evaluation, player acquisition and valuation of the player. That’s what this was invented for.

Now we’re in this – it’s not a revolution, it’s an evolution – how do we take this information and digest it so that the players are able to understand it themselves, put themselves in a better position to perform better, play better and win? At the major league level, it’s about making money and winning a World Series. At the collegiate level, they have to win their conference, they’re trying to go to Omaha. They’re trying to get a ring. That’s what it’s about at the end of the day.

Players aren’t getting paid, so our goal and what we’re assisting with is skipping that five-six year period of learning a lot of the metrics out there for player evaluation, you don’t need that at the college level. How do we go directly to development for those guys and supercharge their programs and help them become more efficient and how they can utilize their time better?

We’ve seen examples at universities because they have restrictions. It’s not like you can practice for ten hours a day. The NCAA has rules and windows that they can practice and have to document hours. That means that you have to become more efficient and have to create individualized player plans. You have to have technology in order to execute that because they can’t have a robust staff of 15 guys. This allows them to maximize their time but also to help good players get better, educate them so that the player does move on because it’s still a small percentage of players that move on to professional baseball.

We get to work with all the different manufacturers that create technology. I get to vet it and play with it and understand it even before the major league clubs do. What I’m trying to find is, what is this going to look like from a playing perspective? What is this going to look like on field? How is this going to apply in practice? How do I take a coach that says I’ve got 20 years of coaching experience and has never used this and shape this into his daily routines and coaching philosophies?

There have been some books written, and I have some friends that have written some books, and they talk about old school versus new school. It’s one school. Our game evolves. At one point in our game, there wasn’t spring training. The idea of training to get better was just playing the game until Branch Rickey changed the game. And he did, he created a system for development. It took a while for adaptation, but now that’s where our minor league systems come from. There’s been evolution as time has gone on and this is just another evolution in our game.

The one thing that you can do with technology, and I use this to identify because I’m a maker of lists and bucketing, is you have the advanced and the ones who are the later adapters. Like the Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria. On the Niña, from a professional perspective, that would be the obvious ones like the Astros, Dodgers, Cubs; early adopters of technology. You’re on the first boat and there are advantages to it. You get the lay of the land but the risk is this: you can take an arrow to the throat.

The largest grouping that you have is that second boat. They’re going to adapt but they don’t want to be wrong. They’re going to wait, technology changes. That’s where the vast majority of universities are at and even major league clubs are at, they’re in that middle road.

Then you have that last boat – kind of the land of the lost – where they’re just trying not to crash into the rocks. The beauty of technology is this: There are specific major league clubs right now that can buy their way back from the last boat to the front boat. There are teams that are purchasing and using technology for the first time and they think it’s for one reason, and there are teams that have technology for four or five years and have gone through the learning curve and are using it for completely different, more advanced reasons.

There’s a reason why clubs have spent millions of dollars on high-speed film. Is it because I want to watch a major league pitcher because it’s easier and smoother to watch the video so that I can make my own objective decisions on his mechanics? While one club thinks we just have cleaner video and it’s much nicer to watch, another one has an AI machine learning with some of the most advanced technology on the planet. And for me, being able to see behind the curtain and work with the technologies and manufacturers and understand just not what they can be, because we’re still in the fourth inning of this. Nobody has this figured out yet.

Just like an amateur player changes every ninety days, technology changes every ninety days. When I see a piece of technology that can be applied in our game, it’s just like scouting a player. If you look at it and go, this is what it is now and it’s not anything great, you’re lost. What can this be? What happens when they make this improvement or what could this be? A great example of that is swing sensors.

Six-seven years ago, when they were first introduced on the market it came from golf; the majority of this technology all comes from golf. I was so excited because I wanted to impress DePodesta. I wanted to introduce this because I had these workouts in January where I’d invite the top 25 players in the Southeast to come in and do kind of a day in the life of a Met. Introduce the player to it, which is huge in building more rapport and understanding the player.

But at the same time, it allowed us to say, let’s see if we can grab some metrics from this. I spent all this time working with the manufacturer, got the sensors and we slapped them on the kid’s bats. And I’ll tell ya, the shit didn’t work. [Laughs.] It didn’t work and it had nothing to do with us, the technology wasn’t ready yet. You expected it and that’s the way people are as you buy technology, you think this thing is going to do everything.

Well, three or four years later, technology gets better, it changes. Now we’re using swing sensors in games at the professional level from A-ball down. Kids have swing sensors in the knobs of their wooden bats. They drop the sensor in the hole and the good thing with it is when they first started to do it nobody really knew what the metrics meant.

I did this huge study on being able to match swing sensor metrics to in-game data. What it provided me was the truth that there are predictors that there might be one slice of the DNA of that swing. What I learned from that study was that I can take the swing sensor and use it with the 14-year-old player who might be 5’11” and 140 pounds, and he’s nowhere near what his physical potential is going to be. So the eyeball test won’t work.

But you know what? This kid has one singular trait that is elite. So what I’m going to do is I’m going to take this player and put him in this bucket, and I’m going to follow this player because he has an elite trait. That’s how technology can help impact the game. And for us, a huge part of this is being able to take that technology and make it more accessible at the amateur game so that we can ID players better, help with their development and find the right fit for the player.

We have a specific product that we’ve introduced where we’ve taken our product for the college market and just done one simple tweak to it: it’s in Spanish. Now we can go to the Dominican Republic and we’re marketing to the clubs in the Dominican Summer League. The idea behind it is the industry is spending more money in Latin America on players than we are in the draft.

Dave Roberts made a comment last year that to me was incredible. He said that the biggest impact the Dodgers made on their organization was when they gave their minor league players full access to the data that they give their players at the major league level. It allows for [a] better transition to the major league level, there wasn’t that wall there for them.

In the Dominican, it’s not here so they have less access and teams have made huge investments in their economies and personnel at the academies. But again, you’re talking about kids that are out of school. It’s not the same social system we’ve got and the priority is their daily training and repetitions. Those kids are taking hundreds of swings and hundreds of ground balls a day.

Their priority is not getting into Stanford, their priority is using baseball as a way to better their lives. When they’re about to transfer over to a complex in the States and they get off the island, now it’s not just the language barrier, social barrier, and coming to the United States and all the obstacles that they already have to deal with. Now, with the change in our game from a data standpoint, they’re behind the eight ball.

Our idea was let’s recreate a very simple interface and take away the stuff that doesn’t matter or won’t be used for player evaluation, and deal with only the metrics that matter to be able to teach the players this is what this is, this is what this means and this is how you can use it to get better.

We’ve had a tremendous response from the major league clubs on it. Initially, everybody has their portals and how they control their information, but they didn’t build them for development. They built them for evaluation and scouting. You can’t give the keys of the kingdom to a sixteen-year-old. But what we can do is take the in-game information the same way we do with the colleges and at the amateur level and provide them a very simple user interface.

A lot of the questions the clubs would have and from an education standpoint, that’s what I spend my time on. What is this going to look like? How is it going to look for a pitching coach in Santo Domingo to be able to connect it with a sixteen-year-old and explain to him his vertical break? How is that going to happen? What is that going to look like?

MMO: It’s exciting that in a sense players are no longer bound by a natural ceiling anymore. We’ve seen players in their late twenties and early thirties improve (Rich Hill, J.D. Martinez, Justin Turner) by altering their approaches using analytics.

Updike: How about this: What if you had it before? One example is launch angle. You’ll hear people just ramble on about launch angle. What we’ve done is we’ve simplified this: damage.

I know the numbers at the professional level: 95, 10. Ninety-five miles per hour exit speed with a ten-degree grade of launch means you did damage. If it’s above that you did damage, if it’s below you didn’t. Well, because we’re the largest holder of amateur data on the planet, I’m able to run regressions at different levels of the game whether it’s high school or college. We break it down granularly, too.

For Division I Power Five baseball, we can go to a coach and say, forget the term launch angle. Let’s think about damage or no damage. Ninety-five, ten. Now when you’re in your practices and have your Trackman on the scoreboard and engaging your players in it, now it becomes a competition rather than just taking hacks during BP. The players are able to see in real-time on the field if they did damage or not. Now we’ve integrated the technology to where it becomes part of their feel aspect to it as well. It becomes not just technology, but holistic, and it’s easier to understand.

We’ve created a graph for when teams log into our software the first thing they see and the narrative that we’ve pushed is it’s a battle for exit velocity. Did your team do damage and did your defense and pitching when the battle of exit velocity against? All you’re trying to do is spread that. The larger the difference of the folds between it, the more successful your club’s going to be. The more that it’s average or equal, you probably have a middle-of-the-road club. If your exit velocity against is higher than your exit velocities from your offense, you’re not going to win.

It’s the 40/40/20 rule in our game: you win forty percent, lose forty percent, but that twenty percent is the difference between a first place and last-place team. Well, that twenty percent is dictated by that battle for exit velocity. And now, all the different coaches that have different philosophies and backgrounds have a starting point of how statistics and analytics impacted our game, but can adapt their existing coaching philosophy to that and blend it.

MMO: Can you describe a day in the life of a scout?

Updike: I’m going to tell you flat out, the Mets were a tremendous organization to work for, tremendous people to work with. My term personally – and I’ve got my Updike-isms – it was sort of a Montessori approach so that I could find my own way.

You have your area, there’s a lot of pre-planning that goes into it because we’ve got to figure out schedules, weather, national scouts that are coming in to get views on players, collection of videos, metrics, along with traditional scouting.

A day for me, let’s say I’ve got a 1:00 p.m. junior college game in Tampa. I’d wake up in Apopka, Florida, and I’d get up at six and I’d drive two hours and get there three hours before the game. My goal is to be at the ballpark before the players get there so I can interact with the coaches.

For the player I’m targeting, I want to see what he does when he rolls into the park. What does he do when he gets out of his car? Is this guy prepared? Is he still asleep? If I’m going there to figure out if this guy can play, I’m not doing my job. I’m there because I know he can play, what I’m trying to figure out is who is this person and how is he going to adapt to us.

There’s this romanticized view of scouting, but the truth is its player acquisition. Does he fit into our system? Does he fit our values system? Is this a player that’s going to supersede the expectations, under-promise, and over-deliver?

I’d go to Tampa and get there early, watch him go through his work. Watch the game, finish the game, jump in the car and then I’ve got a high school game at 2 or 3 p.m. in Orlando. High school is a little bit different because there’s not as much early work and preparation. But same thing, get there as quickly as I can to learn as much about the player pre-game. Once I finish that one, I grab another coffee [Laughs], make some calls in the car and then I’ve got another game in Jacksonville that night. Same routine.

I would start the year with a list of roughly 120 players and at the end, I traditionally turn in a lot of players because I like players. I’m not there to eliminate, I want as much volume as I can. My job is to set up the kid. The crosschecker’s job is to knock them down, their job is to find holes. If the kid is still standing we’ve got the chance to acquire the player. It’s really as simple as that.

But rolling 50,000 miles on a vehicle would not be out of the question, along with a lot of really bad food. I survive on tobacco products and caffeine the entire time. [Laughs.]

We’re driven by this, not because we want a check. The money doesn’t equal the work; I do it because I want to be part of something larger than myself. But even more, some dude gave me the opportunity to play the game, some dude did the same thing that I did. John Ramey was a scout that drafted me, and this one human being had belief in me. This one individual changed the game for me and gave me the opportunity. I never really had to do anything but baseball since and I appreciate that.

The reason I wanted to be a coach, and in particular a junior college coach, is my junior college coach Tim Hill. I make this comment all the time that if it wasn’t for Hill I’d be dead or in jail. He changed my life in a way that no individual ever did, he was a leader of men. You don’t realize it when you’re 23, but I’ll tell you what, when you have the opportunity to interact and impact lives, that’s where it comes from.

Most of the guys that are in the scouting industry have similar backgrounds, and that’s changed because of the industry. But you had something that affected you and it drives you every day. It’s not that I’ve got to make a check or I’m going to get fired, I’ve never felt that way. If I did I wouldn’t have done that job. I did it because I wanted to win, I wanted a World Series ring, I wanted to see guys have success.

The Jordan Humphreys‘ of the world, who’s now on the Mets’ 40-man roster, I selected him in the 18th round [in 2015]. I went to go see him in high school with my son and nobody scouted this guy. Went to go see him one day, he was 84 and touched 86 mph. Not even close velocity-wise to what we were looking for. But he did one thing that was amazing to me: he had elite command. He could throw the ball wherever he wanted.

This kid from Crystal River, Florida, that nobody paid attention to and two years later he’s in our top-30 prospects. We signed him for $150,000 and I had to fight for the extra $50K. And now this kid, who maybe three or four clubs turned in with reports, he’s on our 40-man. That’s what it’s about. We gave him the opportunity and he made the most of it and now he’s in control of his destiny.

The opportunity is what’s important and that’s the satisfaction that comes in it. I seem to be doing a lot of interviews and from a scouting perspective, you don’t hear that a lot. There are not a lot of scouts that are in the media. There’s not a lot of thanks that come in our job. But the thanks come from when you see a kid progress and get better and have opportunities and take advantage of them. The way he has, the way Allan will in the future and Garrison Bryant for Brooklyn this year.

MMO: You brought up how most teams didn’t even scout Humphreys. Can you talk about your process for gathering information on players?

Updike: Networking and your contacts. For me, being a junior college coach in Florida I had to deal with everybody because my competition is everybody. I’ve got a kid that commits to the University of Florida, great, that means he’s on my list because something may happen. He might go there for a year and then comes to JC. Stuff happens.

You build your network of high school coaches, summer coaches, hell, Little League coaches and you listen. Our industry is so dependent on the circuit. If a kid fell off the circuit, clubs aren’t going to write the check for them.

Take Garrison Bryant for example, who was in Brooklyn in 2019 and was the best damn starter we had there. I was actually going to go see another pitcher in our organization that I drafted and they had matched up. I’m sitting there watching the kid that I’m supposed to be seeing that day and then this kid rolls out there and he’s 6’3″, 185 pounds, had a good breaking ball and threw a ton of strikes. I’m like, this guy’s really interesting, who is this kid?

I was the only scout at this game, Christian James was the one I was there to see who not a lot of clubs were on. Then I saw Bryant, so I start working behind the scenes. I’m asking people and they’re like, “Oh yeah, the quarterback. His mom is over there.”

I go over and start having a conversation with his mother. Not introducing myself as the Mets, but just asking some questions. The conversation starts and the game ends up with both kids pitching really well, and I introduced myself to Garrison.

He was a quarterback at Clearwater High School and had a lot of success. They moved from the New England area to Florida specifically for him to play football. For Garrison, he committed to play college football but he also knew with concussions – which he had a few – that he was probably going to be redshirted his first year so he could physically get better.

The more I looked at it I just thought to myself here’s a big, strong athlete and the only time he played baseball was during the high school season. He really didn’t play summer ball, fall ball or on the circuit because he had to spend seven months of the year pursuing football.

As we continued our conversations, I’d go in and I’d go to his house, talk with him on the phone a lot and it was here’s an idea for you, I believe in you. I believe that you can be a major league pitcher. If you have the opportunity to start your professional career, we can provide you incredible training and opportunity to get better. After three or four years, if this doesn’t work out, we’re paying for your education. You’ll be 22, a physical machine. If baseball doesn’t work out, you’ll be able to get whatever university you want to go to enroll, have your education paid for and play collegiate football. Hard to say no, and he said yes.

I’ll tell you what, he took his lumps his first couple of years; he had to do Kingsport twice because he was behind in his development. Then this year, he goes to Brooklyn and was a superstar. That’s the fun part of this.

I remember on day three of the draft, they made a board and called it Updike Day, because I would have these guys that nobody knew of and we would sign them for the minimum amount of money, which doesn’t happen these days anymore. And then after two years, they went in our top 30. It was looking for that aspect of it, we’ve got to be masters of the obvious but what the Mets did a great job of was allowing me to go through my process and my craziness and go after what I really loved, which was that outlier. What happens if this kid gets an opportunity? Is this the type of kid that’s going to make the most of this? Sometimes it doesn’t work out.

As an organization, we had more tenth-round ranked prospects than all major league teams combined. From a scouting perspective, the first ten rounds of the draft because of the crosscheckers and the front office, the eleventh round on are for the area guys, that’s where you make your name. The Mets did a great job of understanding that and they had a history of doing that well. Steve Barningham, who was my first crosschecker and actually brought me into the Mets organization, was something that he had always stressed to me. That was a wonderful aspect of it.

MMO: It also must be so rewarding for you.

Updike: I was in Miami for Pete’s first home run. I was able to sit behind home plate, and it was satisfying. But I knew what this kid was going to accomplish.

When we shored up the 40-man roster, I was actually driving through Iowa and Humphreys called me. And first, it’s like being a dad, my heart drops from my stomach. I answered the phone and you could hear it in his voice and he said, “I did it, I made the 40-man. They put me on the 40-man roster!”

I had to pull over to the side and I’m tearing up right now! Understanding where that guy came from, what he’s done and what he’s had to go through.

We have a 23-year-old, a kid the same age as someone coming out of college, that nobody knew and really identified and clubs passed on fifteen times. And if we didn’t take him, there’s a good chance no one would’ve taken him in the draft! And he’s on our 40-man roster, that’s amazing. That’s the beauty of our game.

He wasn’t a PG All-American, he wasn’t on the cover of Baseball America. But he’s on the 40-man roster. He has the chance to impact the major league club, and that’s what it’s all about.

MMO: Thanks so much for your time, Jon. Best of luck with BaseballCloud!

Updike: I appreciate that. Thank you so much.

Reminder that you can read part one of this interview here.