Since 1901, only eleven starting pitchers have posted the following for their respective careers:

- 250 or more complete games

- bWAR of 80.0 or greater

All eleven are naturally Hall of Fame players, poised with superior arms and the ability to pitch deep into games, something that’s foreign in today’s game due to several factors including the long commitments and vast contracts pitchers sign, the importance and reliance on the bullpen, and health.

The list of pitchers includes Walter Johnson, Eddie Plank, Christy Mathewson, Grover Cleveland Alexander, Lefty Grove, Warren Spahn, Robin Roberts, Bob Gibson, Gaylord Perry, Steve Carlton and Ferguson “Fergie” Jenkins.

Of those eleven players, only one has the distinction of being the first Canadian-born player enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame: Chatham, Ontario’s Fergie Jenkins.

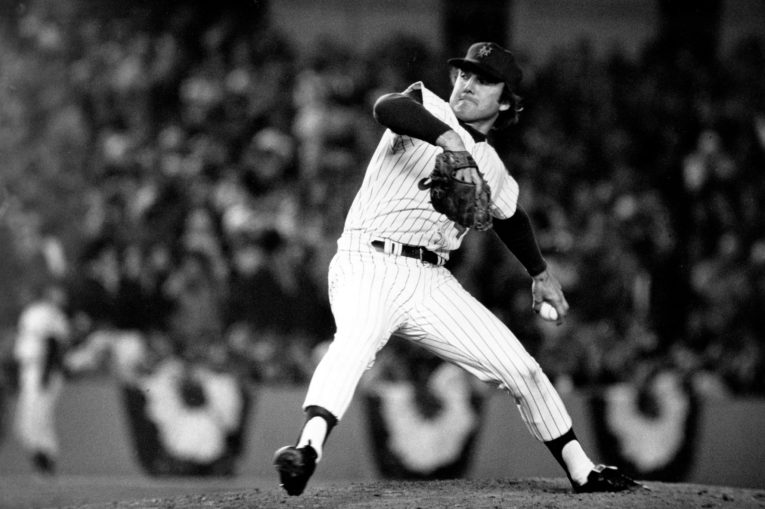

Jenkins, 75, spent nineteen years in the majors, playing for the Philadelphia Phillies, Chicago Cubs, Texas Rangers and Boston Red Sox.

Blessed with a rubber arm, Jenkins’ success and longevity in the game can be tied to the fact that he only appeared on the disabled list just once.

Best associated with the Cubs, which he called home for ten of his nineteen big league seasons, Jenkins is the Cubs’ all-time leader in pitcher’s WAR (53.0), games started (347) and strikeouts (2038), while fifth in wins (167).

The six-foot-five right-hander won 284 career games, winning twenty or more games in seven seasons, six of them consecutively (1967-72).

The 1971 N.L. Cy Young Award winner found success by missing bats and limiting walks, leading the league in SO/BB on five separate occasions while finishing in the top-five ten times. Upon his retirement, Jenkins was the only pitcher to strike out 3,000 or more batters while walking fewer than 1,000 for his career.

Since his last major league season in 1983, only three other pitchers have joined that list: Curt Schilling, Greg Maddux and Pedro Martinez.

Jenkins was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991 on his third attempt. He narrowly joined Rod Carew and Gaylord Perry, as he received 334 votes out of 443 ballots (75.4 percent).

While Jenkins stamped his legacy in baseball history with his consistency and brilliant work on the mound, he found his second calling post-retirement with the foundation he established. The Fergie Jenkins Foundation was formed in 1999 and supports more than 500 charities in both the United States and Canada.

Through its efforts, the foundation has raised more than $5 million in total contributions to charities such as Big Brothers Big Sisters, Special Olympics, Habitat for Humanity, and the Canadian/American Red Cross. Jenkins’ philanthropic work keeps him busy throughout the year, as he travels for fundraisers, golf tournaments, speaking engagements and autograph signings.

Jenkins’ life is one of perseverance, as the Hall of Famer overcame many personal hardships including losing his mother, Delores, to cancer in 1970; losing his second wife in a tragic car accident, and a young daughter less than two years later. These devastating moments could do one of two things: break a person or give them perspective and strength to continue to promote and instill wellness to others.

Jenkins chose the latter.

I had the privilege of speaking with Jenkins in mid-March, where we discussed his foundation, pitching under Leo Durocher, being the only Canadian-born Hall of Famer, and his thoughts on why starting pitchers don’t go deep into games anymore.

MMO: Thanks for your time tonight, Mr. Jenkins. I noticed on your Twitter feed that you teased out a new book you’re working on about the 1969 Cubs due out next January. Can you talk a little about it and your involvement with it?

Jenkins: George Castle is the writer and we’ve tried to interview as many ’69 Cubs that are still alive. Sixteen of the players are gone now, it’s too bad.

But we’ve interviewed Randy Hundley along with Billy Williams, Rich Nye; there are a half dozen guys.

We really tried to get to the point, to put into perspective the real situation on why the Cubs didn’t win in ’69, and why the Mets were so good.

MMO: You also have a chapter in the recently released book, Champions: 15 Inspiring Comeback Stories from Sports & Life. What should readers expect from this book?

Jenkins: The biggest thing is we tried to give the fans an insight that players are human just like everyone else. Athletes that play have problems; athletes struggle with life in general. It’s a daily struggle sometimes.

In my story, I lost a wife and a daughter in a car accident. I lost a mother when I was young and I lost my father right after the Hall of Fame induction. So everybody has a situation where it happens in your life. George Castle and John Schenk wanted to put it down in writing and I volunteered to let the public know what I went through as an athlete and as a person of interest.

I think that everyone has their hole in the wall and a lot of times they don’t want to let people peek into it. Being in the public eye a lot of times, people want to know what made an athlete tick and what they had to go through to be successful. And in my case, a lot of time it was death.

MMO: Can you talk a bit about your foundation, the Fergie Jenkins Foundation, and what its mission is?

Jenkins: We started a foundation 24 years ago. Our main goal was to raise money for the Red Cross in Canada. We had one golf outing with quite a few celebrities: Bob Gibson, Harmon Killebrew, Reggie Jackson. You name the celebrity that I contacted and I wanted to come, and they came.

We had 35 celebrities to come to my event in Canada, close to Niagara Falls in a little town called St. Catharines. We raised a little over $90,000. We paid for all the hotels, meals, the golf course and gave the Red Cross $65,000.

The next outing we put together, I wanted to add cancer research. My mother died from cancer young and she suffered from glaucoma and lost both her sight in childbirth with me. We added three charities and we were able to divide the money up. I’m not sure of the amount now, but when we divided it up, we divided it to three different charities.

From then on, we started to enhance the foundation with a lot of different charities. You name the charity, we’ve donated money or balls, bats, whatever to it. And we’ve raised a lot of money from Special Olympics to juvenile diabetes to Make a Wish to breast cancer. You name the charity; we’ve been involved in Canada and the U.S. over the last 24 years. We’ve donated over $5 million to charity.

MMO: Are you continuing to add new charities?

Jenkins: Over the years, we haven’t really added new ones because of the fact that everyone that writes us wants money. And it’s a good thing, it’s not bad. It’s just the fact that we’ve had maybe 300 charities that we’ve donated monies to or memorabilia, and let them auction the item off and raise money for their charity.

In spring training, we donated money to Make a Wish and so many different church charities. We have a theme every game, whether road or home, we do the charity that’s in that particular ballpark. The Texas Rangers have a charity with the Boys and Girls Club, the Kansas City Royals with Make a Wish. One in, I think Scottsdale, has Big Brothers Big Sisters.

We’ve donated money from memorabilia sales and we’ve had celebrities that have been there like Gaylord Perry, Vida Blue, [Bert] Campaneris, and “Blue Moon” Odom. Pete LaCock, Lee Smith, Bill Buckner, myself; so many different ballplayers that have volunteered their time to go to the ballpark and sign memorabilia. We give them a per diem or pay for their hotel and meals, and we try to make money at the ballpark.

The fans are the individuals that really support the charities because they donate their money. It’s not that you buy the item, you donate your money to get an item. If you don’t want the item you can take a picture with the celebrity and volunteer money and take a photo with a player. It’s all about making people smile.

When you think of an $8,500 check to a charity, or a $10,000 check to the Special Olympics or Make a Wish, people smile. And I smile back because it’s not only my hard work, it’s the volunteers, the people that work at the ball club, and no one gets paid. It’s kind of a volunteer situation. We do pay a per diem to the players that come in and their hotel and meals and transportation, so that helps. The money is taken out of what the fans contribute.

MMO: You were born and raised in Chatham, Ontario. How did you get discovered by a scout in 1962?

Jenkins: Gene Dziadura (scout) came to Chatham, probably in 1959-1960. He was a history teacher that graduated from Windsor University. He came to my hometown basically to live. And the rumor was that there was a young fellow with pretty good talent, and they said you have to take a look at him.

It was during the winter and I was playing hockey at the time. I was a pretty good hockey player. He came to the arena and in that particular game, I think I got into a fight. [Laughs.] I had a couple of penalties.

I was a defenseman and if you were going to score on my team you had to go through the defense to get to the goalie. He asked me after the game, “Why are you so violent?”

I said, ‘Well, I’m a defenseman. People have to come through me to score goals.’

That conversation stopped and he asked, “What are you doing this summer?”

I said, ‘I play baseball 25-30 games and I’m a first baseman.’

He came out that summer and watched me take infield and watched me throw. He said, “With your arm, maybe you should try to pitch.”

I said, ‘Well, we’ve got pitchers on our team. I don’t want to pitch, I want to play first base. I’m a regular ballplayer.’ I was a pretty good hitter.

Long story short, within a month, he convinced me to start throwing at a gymnasium. Two years later, I signed a pro contract with the Phillies at 18-years-old. I started pitching at 16, I threw a no-hitter, a seven-inning no-hitter. We didn’t play nine innings in some of the games. Pitching didn’t come easy, but I worked at it and lo and behold I signed a pro contract at 18.

I played in the Philly organization for two and a half seasons, got to the big leagues in ’65. Got traded to the Cubs in ’66, and under Leo Durocher and the Cubs, I put some numbers up and was successful.

MMO: You were in the bullpen with the Phillies, and when you were traded to the Cubs you were moved to the starting rotation, where you then took off. What was that transition like for you going from the pen to rotation? Were there any particular adjustments you needed to make? Is it true that Durocher was the one that wanted you to start?

Jenkins: Yeah, I think it was Leo that wanted me to start but it all started in the Philly organization. I was a starter in the minor leagues. I pitched for Miami, Chattanooga, and when I got promoted to Little Rock, they had a lot of pitching, so they wanted me to try and come out of the bullpen. Which I did. I had a few starts but I pitched long relief. When the Phillies brought me up in ’65 for the tail end of the season, which they call getting a cup of coffee, that September call up they had me in the bullpen.

I pitched behind Chris Short, Jim Bunning and Ray Culp. I was in the bullpen so when I got traded to the Cubs, they had seen me work the bullpen. Leo asked me, “Do you feel comfortable pitching out of the bullpen?”

I said, ‘Yeah, that’s what the Phillies wanted me to do.’

I had a rubber arm and I didn’t mind being considered to stay in the bullpen, which I did. I got about 50 relief appearances and then mid-August he said, “I’ve seen you pitch enough out of the bullpen. I’m going to give you a starting opportunity.” So he did. I ended up beating Atlanta and I beat a couple of teams. I ended up winning three or four games the last month and a half of the season.

He took five pitchers in his room in late September of ’66, we already lost 103 ball games that year. He took Joe Niekro, Rich Nye, Kenny Hotlzman, Bill Hands and myself and he said, “Come Spring Training of ’67, you five individuals will vie for four starting spots.”

We end up working hard enough to get that opportunity, and I was the Opening Day pitcher in ’67, Kenny Holtzman second, then Hands and Rich Nye. The four of us were the starting rotation for that ball club. All 22-25-years-old at the time.

MMO: Your 1969 Cubs team featured future Hall of Famers such as yourself and an overall fantastic roster. Heading into September, the Cubs were up five games in the standings before the Mets went on their historic run to win the NL East. Can you talk a little about your memories from that season, and why you think the collapse occurred?

Jenkins: Like you said, we had about a five and a half-game lead with about 15 or 16 to play. The Mets played .900 ball and we played .500 ball. We got caught by the Mets in a series, we got caught by St. Louis in a series, and we went to Philly and fell out of first place.

They were called the ‘Miracle Mets’ for a reason; they just came on and they had a pretty good pitching staff. Gil Hodges used a five-man rotation and it just seemed like it worked for that organization.

As I said, we fell out of first place and that team ended up beating us, Atlanta, and then they beat Baltimore for the World Series. Tug McGraw kind of coined the phrase the ‘Miracle Mets.’

MMO: From 1967-74, only Gaylord Perry, Bob Gibson and yourself posted a WAR of 50.0 or greater, an ERA+ of 120 or better, and 30 or more shutouts. You won twenty games six straight seasons (1967-72) and seven times in an eight-year span. What memories stand out for you from that time frame, and what made you so dominating on the mound?

Jenkins: I think the fact that in high school I ran track, I wasn’t afraid to run. I kept my body in really good shape. Other than that, you have to have good teammates, too. A good offense and defense.

As I said, I had a rubber arm. Out of my 19 seasons I pitched, I never had a sore arm. It could’ve been genetics, it could’ve been the team I played on, the windup; there were so many intricate things that went into that.

I stayed healthy, I didn’t get hurt. I had one injury in 19 seasons, that was it. Some guys fall into that evil thing of getting hurt and being on the disabled list. I was on the DL one time in 19 years, so I was very fortunate enough to stay healthy, to play with pretty good teams that scored runs for me, and I won ball games.

I can tell you bonus babies that got tons of money, tons of money, that never made it out of Double and Triple-A and never got to the big leagues. I consider myself pretty lucky.

MMO: You pitched over 250 innings ten times in your career, and five of those ten were for over 300 innings. What was the biggest key for you to be able to be counted upon to pitch so many innings per season? What are your thoughts on the way starters are utilized in today’s game?

Jenkins: Staying healthy was something that I thrived on, and to be consistent. The number one thing was I kept my body in great shape, I threw all the time, and I had a rubber arm. I don’t think that these players nowadays are given the opportunity to complete a ball game. I averaged about 18-22 complete games a season, and had 30 one year [1971]. I just think that some of these fellows are strong athletes.

I never lifted weights, that’s one thing I tell youngsters now when I talk to coaches and players at clinics is I never picked up weights. The most weight I ever picked up was a five-ounce ball. [Laughs.] I did sit-ups, push-ups and different exercises. I used rubber bands when that was a big thing to have back in the ’60s and ‘70s. They were color-coded: yellow, green, blue and black. I’d do exercises with them or in the doorway, isometrics.

Now, pitchers are obligated to lift twice a week. I know the Cubs do it. I don’t know about other ball clubs. They have to lift and work out twice a week with weights, I just never did it. The everyday players can lift whenever they want, I imagine. Athletes are bigger and stronger supposedly, but they’re not any better, believe me. There’s no Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale, Bob Gibson’s, no [Juan] Marichal, no [Tom] Seaver’s. And for sure you’re not going to see a Willie Mays, Hank Aaron or Mickey Mantle. They’re not around.

There are 30 teams now, when I was around there was 16, and then expansion happened. I just think the era that I pitched in was the era of pitching with Jim Palmer, [Mickey] Lolich and Denny McClain. There were so many good pitchers that played in that era and I can name, gee, twenty. We’d win now and we’d win big, believe me. [Laughs.] We’d make these young guys look sick.

MMO: Noah Syndergaard packed on muscle in the offseason last year and missed most of the year with a torn lat. Do you think guys are lifting too much today?

Jenkins: It could be a combination of a lot of things. I think as a pitcher you need elasticity. You need long, lean muscles. You don’t need bulk. I’m not saying bulk’s not good, but like I said, I didn’t mess with weights. I used to stretch all of the time and I ran. That was our theory, even with the Phillies when I was in that organization. We had to run twenty steps a day, regardless if you’re relievers or starters. When I came over to the Cubs, I had Freddy Fitzsimmons [as pitching coach], and then my second coach was Robin Roberts, then I had Joe Decker and Larry Jansen.

I had Cal McClish with the Phillies and he talked about throwing and running. That was the theory with the Phillies organization. When I came to the Cubs, it was almost the same type. That’s what the pitching theory was for most ball clubs in the sixties, throw and run, throw and run. Forget about weights, we didn’t have weights in our locker room. If you wanted to lift weights, you had to go to a health club to pick up weights.

There were a few athletes that brought weights in later on in the ‘70s, but not what you see now. It’s like a Gold’s Gym/L.A. Fitness, where every ball club has a weight room. If you want to do it, go ahead and do it. If you think it’s good for you, go ahead. Why not? But I just didn’t have an opportunity to do a lot of weights, that’s why I didn’t do them.

MMO: You pitched under legendary manager Leo Durocher from 1966-72. What were your impressions and memories about Leo during your time?

Jenkins: Tougher than a night in jail, and I’ve never been in jail! [Laughs.] He was just tough. In 1966, when I got traded from the Phillies to the Cubs, we had to play his way. He wanted the format that he designed and he wanted guys to play fundamentally, because he came out of some good organizations with the Giants and Dodgers. Fundamentals were a very big part of what he tried to get across to players. We had to learn to play his way and we improved from ’66 to ’70. We improved from winning less than 60 games to now 70, 80, 90, to be a contending ball club.

Those three years, from 1968-70, if we would’ve had a little better bullpen who knows what we could’ve done. Bullpens were something that really was important to our ball club later on in my career. If you had a good bullpen, you didn’t have to pitch nine innings. If you had a bad bullpen, starters stay out there.

We had Phil Regan a couple of seasons, [Ted] Abernathy, Bob Locker for a while later on with the Cubs. When I got traded to Texas, we had Steve Foucault, who had a rubber arm and threw pretty good. When I went to Boston, we had a couple of really good bullpen people, too.

Then I came back to Texas, had a decent bullpen. Then back to Chicago, and Lee Smith and Willie Hernandez were just learning how to be bullpen people. They threw the ball pretty hard, Lee Smith had a good fastball and slider, Hernandez had a screwball. When we traded him [Hernandez] from Chicago to Detroit, he ended up winning the Cy Young throwing that screwball.

It’s just part of the game that’s changed a lot because the bullpen now is more important than the starting staff, which shouldn’t be that way. But it is.

MMO: You’re right, the bullpen has become so essential in today’s game. Especially with the advanced metrics and having starters on strict pitch and inning counts.

Jenkins: Yup. You throw 100 pitches and your day is done. If it takes five innings or you can pitch it in six. Some guys have real good control, and if they can get you into the seventh, fine. But you’ve got the specialty guys, you’ve got the left-handed and right-handed specialists. Then you have the holders, set up and closer. You have eight to nine guys sitting in the bullpen, and a lot of guys don’t get a chance to pitch. It all depends on the tempo of the game. The game’s out of hand? Boom, get him up, get him in. But if a guy’s pitching really consistent ball, maybe a one or two-hitter, and he’s into the seventh of eighth, hey, the bullpen’s just sitting out there. If you’ve got four or five consistent teams, guys are not going to play, and they’ve got to throw.

A lot of times when guys – especially in the bullpen – don’t perform I think on a consistent basis, they walk people. Walks are a death threat to ball clubs. An opening walk in an inning score eight out of ten times. It’s just crazy.

There’s nothing wrong with the bullpens, it’s just that they really have not focused on starting. If you’ve got two or three guys that can start, fine, you’ve got a decent ball club. But if you’ve got four or five guys who start, you’ve got a winner. You’ve got a winning ball club if you have five good starters, but it just doesn’t happen.

MMO: You were a multi-sport athlete growing up. How did you end up playing for the Harlem Globetrotters during three offseasons?

Jenkins: [Laughs.] That was kind of a lucky situation. Lou (inaudible) was the marketing individual with the Globetrotters. They had a downtown office in Chicago on Michigan Avenue. He came out to the ballpark and wanted to know if I was going to go back to Canada, and if I would like to do about a dozen games with the Globetrotters. I didn’t have to say I’ll think about it, I said, ‘Sure.’

This was in September, and it just so happened we had an off day, so I phoned him. I knew [Shon] Crosby and a couple of the other guys. I [had] never met Meadowlark Lemon or Bobby Joe Mason or Curly [Neal], the mainstay of the team. He said bring your sneakers, shorts and a t-shirt and work out with the team.

I went to the local gym right in the downtown Chicago area. Basketball was my second sport so I just kind of fell right into it. I played the third quarter every night; I played about 180-185 games in three off-seasons. I really enjoyed it. It kept me in shape and it was a lot of running. If I scored, fine. If I didn’t score, hey, that happens.

I was the guy in their baseball skit to give up the home run each night to Meadowlark. I did the out of bounds, the referee and the figure eight. In the course of three off-seasons – 67, ’68, and ’69 – I’d played about 180-185 games. Madison Square Garden, old Cobo Hall, Olympia in Detroit; you name the arena and some of the big campuses and I got the chance to play with the Globetrotters.

The skit was all of a sudden the third quarter starts, and Curly says, “Let’s play baseball.” So Jackie Jackson says he wants to be the pitcher. Jackson throws the ball maybe three or four feet over Meadowlark’s head, and Curly says as loud as he can, “Hey, you’re no pitcher! We’ve got a twenty game-winner on our bench.” And the crowd’s going who the hell is that? “We’ve got Fergie Jenkins of the Chicago Cubs, twenty game-winner.”

So I take my sweats off, take a couple of warm-up throws and boom, Meadowlark hits the third pitch for a home run into the stands. The basketball was smaller then and he hit it pretty hard, so it went way up in the stands. He’s running the bases and he gets to a couple of strides before home plate and he goes, “Curly, come on, hit a home run tonight!” And Curly goes, “I got you tonight, Meadowlark.” He pretends he’s Superman and slides into home plate.

When that part of it’s over, I got down underneath the hoop and if he doesn’t get the rebound I’d throw it back, and if he doesn’t do it the second time either Jackie Jackson dunks the ball or I dunk the ball. I was able to dunk when I was younger. So that was just a part of the skit. I didn’t get a big hand, it was, Hey, Fergie Jenkins can play, type of thing. If I had the opportunity on a fast break to score a couple hoops, fine. It wasn’t my game to go out there and be the star, because it was Meadowlark, Curly, Leon Hillard, and all of those guys. But it was fun. In the third quarter, I got a chance to play and in the fourth quarter, you sit on the bench and relax.

MMO: It’s certainly a great way for you to keep in shape during the offseason.

Jenkins: Oh yeah, definitely. The running was good, plus we had shootarounds. We’d travel into a new city almost every night except for New York where we’d play maybe three games in Madison Square Garden and two or three in Olympia in Detroit. We played on the aircraft carrier in Indianapolis. It was just a fun, fun tour for three off-seasons.

I would’ve loved to continue with it, but you just can’t. It didn’t wear me down but when it came January I had to get ready for spring training. [Laughs.] It was a fun three off-seasons.

MMO: What does it mean to not only be in the National Baseball Hall of Fame, but to be the only Canadian-born member enshrined?

Jenkins: I’m pretty proud of that situation because of the fact that I’m the only Canadian right now. I think Joey Votto’s got a pretty good opportunity if he keeps putting up numbers, he’s Canadian and from the Toronto area. Larry Walker just can’t seem to get the amount of votes, 75 percent of the votes to get voted in. I’m pretty proud of it. In my career, I put up some decent numbers and got the opportunity to get voted in on my third ballot.

First ballot I was up against [Carl] Yastrzemski, [Johnny] Bench, and a few other guys. Gaylord was on that ballot, too. The next ballot, in ’90, they put in [Jim] Palmer and Joe Morgan. So Gaylord Perry, Rod Carew, and I went in together in ’91. When you’re put on the ballot, you’ve really got to think about it; the voters that vote you either dislike you or like you. [Laughs.] There are like 500 reporters that cast the ballots and you’ve got to get 75 percent of the vote. I was very fortunate.

MMO: It seems at times it’s more of a popularity vote, where if a player wasn’t always available for requests or rubbed some writers the wrong way they’re now taking exception through the voting process. That along with strategic voting and so much internal debate over whether someone deserves to be enshrined on the first ballot or not.

Jenkins: Right, like you say it’s popularity, sure. But I think because of the fact that a lot of these athletes had great careers, a lot of them really, really deserves the vote. Some of the guys that have fallen short had to wait maybe an extra year, like myself. You have to wait your turn. First ballot guys, sure they belong in. I mean, there are so many first-ballot guys: Rod Carew, Ken Griffey Jr.

Andre Dawson had to wait nine times. Jim Rice should’ve never waited fifteen years. That’s crazy. The guy had a great career. Same with Goose Gossage and Lee Smith. He led the league in saves for many, many years. When he retired he had the most saves going, 478 saves, and I’ve known Lee a long time, he should’ve been in the Hall of Fame years ago. Now he’s trying to get voted in with the Veterans Committee. Same with Jack Morris, the guy should’ve been first ballot. It’s just too bad you have to wait. But that’s the way the voting goes.

The Hall of Fame is a museum, it’s not baseball when you think about it. They vote the sport that you played, and you get voted in. A lot of times, I just think guys shouldn’t have to wait. Roger Maris belongs in the Hall of Fame. Jim Kaat has one less win than I had, one less win, and Tommy John has four more wins than I have. It’s crazy. Bert Blyleven had to wait a long time, he has three more wins than I have. But these guys deserve to be enshrined and unfortunately, they don’t get the votes because all of a sudden they get left off the ballot. It’s crazy.

In some instances they’ll get their due. It won’t take long, but they’ll get in. Maury Wills, Dick Allen, I can mention a lot of guys I played against that are deserving to get into the Hall of Fame. Luis Tiant, he’s got more wins than Drysdale, more wins than Koufax, and he’s not in the Hall of Fame. Come on! I just think that when you have such a good following of athletes and the way they played, they’re deserving of it.

MMO: What are your thoughts on admitted and or suspected steroid users gaining entry into the Hall of Fame?

Jenkins: It’s going to happen. These guys are going to get voted in. Like I said, it’s a museum. They’re putting in the player’s accomplishments. It’s unfortunate Pete Rose was suspended for life. If he had a good lawyer, he should’ve been suspended for five-seven years, not for life. I played against Pete Rose for many years, what a heck of a ballplayer he was. ‘Charlie Hustle’ could play. An All-Star at five positions, he’s the only guy. He did it all, and unfortunately, he’s not in the Hall. But his achievements are.

If you go to the Hall of Fame you can go in the Cincinnati part and see all of his achievements: the bat, glove, and uniforms. Same thing goes for [Roger] Clemens, [Barry] Bonds and all of these guys. Their achievements are all there. Sammy Sosa, they’re all there. Unfortunately, I think within time it’ll all change. It’ll all change.

MMO: When you look back on your career, what are you most proud of?

Jenkins: I stayed healthy my whole career and put up some numbers. Winning 20 games six years in a row. I’m not saying it was easy, and it wasn’t hard, but you have to play with good teammates. I look back now and I was fortunate enough to stay healthy, and when I was called upon to pitch, I pitched. I went out there and tried to do my job.

I roomed with Ernie Banks, Dwight Evans with Boston, you could room with whoever you wanted, black or white, it didn’t matter. You were athletes, you played with each other, and it was like a family. I had some great managers: Billy Martin, [Don] Zimmer, Pat Corrales, Durocher and Gene Mauch. You went out there because you were an athlete and you played for the team and the manager. When I played, there were no names on the uniforms, you played for the name on the front. Over the last decade or so they put the names on the back of the uniform so fans could see who they are. [Laughs.]

The fans knew. You see No. 44 in Atlanta, you knew exactly who that was, Hank Aaron. Number 24 with San Francisco, Willie Mays. Nine with Oakland was Reggie Jackson. As long as you saw the number, you knew who it was. I wore 31 most of my career, and I’m Fergie Jenkins. [Laughs.] [You] didn’t need a name on the back to know I was Jenkins.

When I left Greg Maddux took it. I just think in the ‘60s and ‘70s you didn’t need names on the back of the uniforms. Twenty-one with Pittsburgh, [Roberto] Clemente. Eight with Pittsburgh, Willie Stargell, you just knew who they were. That’s the era that I played in and I’m pretty proud of that era, because I had the chance to play against some great athletes. Mickey Mantle, Roger Maris, [Harmon] Killebrew; it was fun and I’m pretty proud of that.

MMO: There was such an infusion of talent from that era, you really started seeing some great talent from all parts of the globe.

Jenkins: It was, it was. There were so many Cuban players. The Dominican players weren’t that popular. They had some guys from Puerto Rico: Clemente, [Orlando] Cepeda, [Jose] Pagan. There were a few from Puerto Rico but Dominican players didn’t come along until the late ’70s early ’80s. Back then, they had a lot of Cuban players. There were so many good players out of Cuba and Puerto Rico, and for the last decade or so it’s been all Dominicans now.

It will evolve again. They’ll be a lot more Canadians coming through. We’ve got some players from Holland and Germany, so it’s a game that if you’re an athlete and you’ve got some ability baseball can be the right sport for you.

MMO: I read that you received a ring after the Cubs won the World Series in 2016. Can you talk about that?

Jenkins: When they won they gave rings to Billy Williams, Ryne Sandberg, and myself. And one to Ron Santo and Ernie Banks. They have a museum there and the rings are there at the ballpark. Five Hall of Famers they gave rings to, I was really grateful.

One nice thing that happened was I was the first player on the field to get a ring presented. When the players came out, Anthony Rizzo, a really class guy, said, “Thanks for being a Cub.” Some of these guys know the history of the game; the ten years I pitched and coached for the team was well over fifteen years. And I enjoyed it.

I’m still working with the team and I enjoyed my time with the Cubs. I look back and that’s where my career really started, that’s where I got the opportunity to be a starter.

MMO: I can’t thank you enough for your time today, Mr. Jenkins. Thank you for reliving your Hall of Fame career with me tonight.

Jenkins: You’re welcome. Thank you.

Follow Fergie Jenkins on Twitter, @31fergiejenkins

Visit Jenkins’ website, https://www.fergiejenkins.ca/site/home

To order Champions: 15 Inspiring Comeback Stories from Sports & Life, click the link here.