Ned Colletti grew up in Franklin Park, Illinois, just a train and two bus rides away from his beloved boyhood team, the Chicago Cubs.

Colletti and his friends would dream of someday playing in the hallowed confines of Wrigley Field. They spent their free time playing baseball, talking strategies, and learning the sport.

While many young children dream of reaching the majors one day in hopes of having their moment in the sun realized, just as they had visualized as they stood on vacant makeshift fields or organized parks during their youth, Colletti would forge a different path into the game he so cherished.

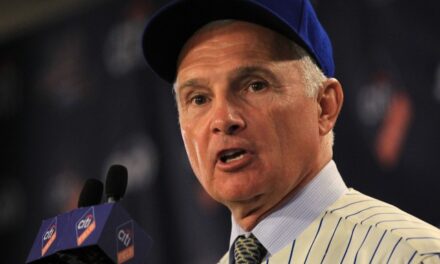

Colletti, 63, spent 30 plus years working in Major League Baseball, beginning his career with his childhood favorite Cubs. He started out as one of a three-person team in the public relations department, eventually growing within the organization to serve as a top aide to three general managers.

Following his 12 years with the Cubs, Colletti served as assistant GM of the San Francisco Giants, an indication that Colletti’s insight was valuable and progressing towards one day landing in the “big chair” himself.

While still employed by the Giants, Colletti would receive a phone call in late October of 2005. It was his former MVP second baseman Jeff Kent, who had signed with Los Angeles one year prior.

A personal favorite of Colletti’s, Kent told him that he had finished a conversation with then Dodgers owner, Frank McCourt, who had relieved Paul DePodesta of his general manager duties earlier on that same day. Kent expressed to McCourt how he felt Colletti deserved a chance to interview for the open position, a flattering sentiment Colletti was appreciative of from his former player.

Fast forward several days later to November 3, two days after Colletti was allowed to speak to another club if the team asked and received permission from the Giants. The former Giants president and managing general partner, Peter Magowan, called Colletti into his office. He had news for Colletti that would forever change his career in Major League Baseball: Frank McCourt had called to ask permission to interview Colletti for the open GM position in Los Angeles.

After multiple interviews with the McCourts, including a full twenty-four hours of interviewing over parts of three days, Ned Colletti was named the 10th general manager in the history of the Los Angeles Dodgers on November 16, 2005.

During his tenure as Dodgers GM, Colletti worked under the McCourts, whose drama-filled life played out in the public eye, which included a contentious divorce and strict budget restraints for the club. Creativity and turning a broken Dodgers culture around were always at the forefront for the ever-busy Colletti, as he looked to turn the tides and rebuild the Dodger brand.

When the new ownership took over, led by Mark Walter and the Guggenheim Baseball Management in 2012, Colletti finally had the chance to make big trades; not having to worry about ensuring that other teams were going to pick up a majority of the player contracts.

Equally as important, under the new ownership, Colletti was able to reinvest into the Latin American market. Under the McCourts, the Dodgers international signings fell under the wayside, with buscones (agents) not even sending their players to the team’s Dominican academy.

The life of a general manager in baseball is one of extreme sacrifices, where the career becomes more than just a job, but a lifestyle. Colletti outlines and explores in great detail the inner workings of a GM in his memoir, The Big Chair: The Smooth Hops and Bad Bounces from the Inside World of the Acclaimed Los Angeles Dodgers General Manager.

Colletti recollects his humble beginnings in Chicago all the way through his nine-year tenure as the Dodgers GM, interspersing personal stories and memories that helped shape his career along the way.

I had the privilege of speaking with Colletti in late January, where we discussed writing his memoir, tenure as Dodgers GM, signing Justin Turner to a minor league deal and what he considers his most memorable trades.

MMO: What prompted you to write The Big Chair in the first place?

Ned: When my job changed in October of 2014, I suddenly had a lot of time. The GM gig is pretty much all-consuming; one day you’ve got that and the next day you’ve got the day off. I thought it would be worthwhile just to chronicle some of the things that I’ve seen, some of the people I had the chance to meet during the ride.

I started writing and I would write probably from 10 PM to 3 AM, four or five nights a week. Not in book form, kind of in journal form. I just wanted to clear my mind. I did that for four or five months and let it sit.

I was at dinner in West Hollywood one night and I ran into an old sportswriting friend named David Israel. He wrote for the Chicago Tribune, he had probably the top sports column in the newspaper and across the city thirty years ago. He and I know each other a little bit and so he called me over to the table he was sitting at and he introduced me to David Vigliano.

I sat down and he looked at David and said, “If this guy ever decides to write a book, you’ve got to represent him.”

And David said, “I know who you are. I imagine you have a tremendous story to tell. Have you ever thought about writing a book?”

I said, ‘Well, I’m about 400 pages in right now.’

He goes, “400 pages?”

I said, ‘Yeah.’

And he asked, “Who’s going to represent you?”

I said, ‘Nobody,’ and he told me that was crazy. I said, ‘Not really, I don’t have any intent to sell it. I just want to write it.’

He talked me into giving him a look at a few different chapters and so I did. We went to work at putting it more into book form than journal form, and started sending it out to publishers who were excited to read it. That’s how it kind of came to life.

I spent most of my life looking forward and always trying to climb the next mountain and I think people have always told me one day it would be healthy for me just to go back and reflect once in a while.

For forty years – maybe more than that – since I started college, I’ve been on this quest to achieve. You never really look back and never really take into account where you’re from or how you got to be where you got. It was kind of a reflection piece, a chance to stop time for a minute and look back on my life and times and how I grew up. My parents, where I grew up and different people along the line helped my career and challenged my career, and in some cases, derailed my career. [Laughs.]

MMO: For those who haven’t read your book, can you briefly describe the day-to-day operations and life of a general manager? After reading your book it seems extremely taxing, as you’re always on the move and essentially working upwards of 18 hours a day.

Ned: It’s a lot of conversations, a lot of communication. It’s also a lot of predicting human behavior, I think. It never does end. There was one day I woke up in Chattanooga, Tennessee, to watch a day game of our Double-A team. That night I was in Nashville, Tennessee, watching our Triple-A team from Albuquerque playing in Nashville. The next morning I was flying to L.A. and catching the early game at Dodger Stadium. So I’m in three different cities, three different time zones, within about a day plus. Same thing as when you scout.

There’s a story in the book about how Brian Sabean and I met at the Atlanta airport and took a flight to Savannah, Georgia, picked up by two scouts. This was a Saturday morning. [We] drove into the countryside to watch Adam Wainwright throw, a young Adam Wainwright, high school Adam Wainwright.

We watched him throw then drove to Atlanta for a game, continued to drive over to Auburn which is on the corner of the Georgia/Alabama border. Saw a game at Auburn, then drove into Montgomery for the evening. Got up and went down to the University of South Alabama and saw two games. Then went over to Biloxi and saw another one. This was all within 36 hours, but that’s what we did. You tried to maximize every day.

Sometimes you can stay for the whole game and sometimes you had to stay for one at-bat and make a judgment on one at-bat, or make a judgment on one inning pitched. Brian and I were [in] one place, I think it was with Jeff Weaver, we watched a bullpen. Brian says, “This guy’s not falling to us.”

We got into the car and drove off. And he was right, so that’s part of it.

The international piece of it is also different. You go to the Dominican Republic, I know there are resorts down there, I never saw any of them. We were kind of in the jungle, out in the wild trying to work players out and makeshift fields, not really a backstop and not really dirt. Grassy fields with cattle in the outfield and you’re just doing the best you can to evaluate tools at that point. But the cycle never ends. It’s not a job as much as it’s a lifestyle, and you’re always thinking. You’re always on the go.

You get into this routine, it’s a great routine. It does sacrifice a lot of your other life, a lot of your personal life. A lot of your health sometimes gets put in the back while you go and try to find a player or try to make your own team better. Somebody used to tell me, “Do you realize how many parents’ kids you’re making millionaires while your own kids sit at home?” And there’s a little bit of truth to that, you know?

MMO: In the book, you mentioned how the San Francisco Giants (who Colletti had previously worked for) would not let you bring over anyone from their organization when you were hired as GM of the Dodgers. Isn’t that pretty rare where a team wouldn’t let you bring some of your closest associates over with you? And how much of a disadvantage was that for you to start your Dodgers tenure?

Ned: Well, you’re right. That’s a great point. It was one of the great challenges. There were two factors. First off, not being able to bring anybody, which the Giants were at that point in time happy to do. [Laughs.] It put me at a disadvantage because what you have to do in that position is you need to learn who everybody is. You need to know how they think, how they evaluate. Everybody evaluates differently. It’s like school, some are easy graders and some are tough graders. You have to figure out who is telling you what for what reason. That takes time, that’s the first thing.

The second thing is the job that I had taken I didn’t get until a week before Thanksgiving. We had no manager and no coaching staff, so we were technically six to seven weeks behind the rest of baseball. Not only am I going to a new team, a team in the same division, a team in the second-largest market in North America, but I’m going six or seven weeks late with a staff that I really don’t know that well, except to say hello to. With a team that had lost 91 games the year before. The Dodgers were 71-91 in 2005, the second poorest record in the history of the LA part of the franchise.

Everything kind of came together at that point and I didn’t have any time to feel sorry for myself or say, ‘Well, this isn’t too good or that’s not too good.’ We just had to get to work and I think the first three weeks I was on 18 different flights, flying all over to interview managers and talk about philosophies and keep my pulse on the free-agent market which had already opened.

We had a team that had a lot of key players on it that were hurt and had a lot of key players that were no longer key players. We had a lot of players that were brought up and candidly they weren’t big league talent.

We had a lot of work to do that first spring and I spent a lot of time with the owner, Frank McCourt. Which is a little bit unusual as your inner circle rarely contains the owner of the team. I needed to develop an inner circle and that was going to take time. Patience is probably the number one attribute that a general manager has to have to be successful. I had to have patience, but I didn’t have time.

MMO: You write candidly about the McCourts in your memoir. Though you, Frank and Jamie McCourt had a reasonably strong relationship. How difficult was it to navigate through the high-profiled divorce that was played out in the media and having the financial constraints that you did early on with the Dodgers?

Ned: Well it did, they were challenges. But organizations have challenges and personality conflict. I think it taught me a very valuable lesson, and that is there are some things we try to control and try to fix, and they’re really out of our jurisdiction to do so.

I would tell Joe [Torre] this, because he managed during that time, [and] Donnie [Mattingly] managed during this period of time, I would say, ‘Look, all we can do is concentrate on what we’re responsible to do. That our payroll continues to get lower, other teams are going up and we’re going down. We have some other issues that we hear about, but there’s nothing we can do about any of that. So let’s spend our time and positive efforts on things that we can change and make better in a positive way. If we can’t do that, we’re wasting our time with what we’re thinking about.’

It did us no good to think about a divorce. We had nothing to do with it. What were we going to do about it? It was a waste of time to think about bankruptcy; what were we going to do about it? Nothing. So all of these different factors with payroll going down, what were we going to do about it? We were going to have to be more judicious in our selection process.

We were going to have to get players we acquired have their contracts sent with them, which we did. We acquired a lot of players that the other team paid the freight coming back our way. We had to get creative and we had to figure it out. But nobody was going to feel sorry for you. In fact, most of the league was happy for us that we had what we had.

It taught us a lesson: concentrate on what you can make better. Things that are out of your control, things that agitate you that you wish were different, let’s not spend a whole lot of time wishing about something to be different because it’s not going to make it any better wishing it were.

MMO: When you were looking to hire a manager, one such candidate you had met with was Terry Collins. However, it wasn’t to interview him for the managerial position, as your predecessor Paul DePodesta had in mind. Can you talk about your interactions with Collins?

Ned: I knew when I had taken the job and Frank had told me that Paul had an interest in Terry, and Frank wasn’t real keen on that interest at that point in the process. I still needed to meet with him; he was director of player development and he did a tremendous job here. I went to Florida and met with him for a couple of days.

He was agitated, in my opinion. In my opinion, he was hurt, and he didn’t necessarily want to be sitting across the table from me and I think at one point I said, ‘Hey look, I didn’t do anything here. Everything that is agitating you is well-founded on your part, I understand it. But I’m not the person, I didn’t do anything. I was working with the Giants when that all went down. I need you, and I have great respect for you. You’ve done a tremendous job here. I want to work closely with you and we’ll see what time brings as things go on.’

I think we ended up having a decent rapport. I know he was tremendously helpful to me on the player development end. You look at some of those great young players that came up through the system [and] they had his mentality and gamesmanship, his attention to detail in their DNA. You had [James] Loney, [Chad] Billingsley, [Jonathan] Broxton, [Russell] Martin, [Matt] Kemp and then [Clayton] Kershaw’s first days as a professional, Terry Collins ran player development. He had a lot to do with it. The more I got to know him, I respected his candor, I respected his knowledge, his work ethic and his willingness to express himself.

Some people don’t like anyone to know what they’re really thinking because maybe they don’t know how strong what they’re thinking is. I always sought counsel and information from Terry because I knew I’d get the real version. I wasn’t getting something filtered, the players weren’t going to get anything filtered, they were going to get the truth as Terry Collins saw it. And I admired that.

Many times, when he went to manage in Japan, I missed him. I missed that approach, his knowledge, his intellect and his expression of how to become a really good player. And he was right, he had a great, great influence on this organization at that stage.

MMO: You write about analytics and how your front office incorporated the advanced stats into making judgments and decisions on talent. Talk a bit about your utilization of these analytics, and when you started to notice such a shift taking place in the game.

Ned: People view me partially wrong, I might add, that I’m not into analytics and I’m more of a scouting old school evaluator. I started out in baseball and it was simple analytics, before computers and companies that kept track of different things. That’s really how I got my first, not my first job, but my first promotion and first became a serious contender for upward movement in the Cubs’ organization, was by doing analytics for our manager and another former Mets coach, Jim Frey. Jimmy had done it with Earl Weaver, as a coach in Baltimore, and he asked me, “Can you do this?”

There was only one way to do it and that was by hand. To go back and research hitter/pitcher matchups, lefty vs. righty, different places in the batting order, close and late, runners in scoring position; we kept all of that. But we did it by hand, we went back through box scores and play-by-play and did it by hand.

It took us a full winter, the winter of 1983 and ’84, it took us a full winter to do it. We went back through the Sporting News and back through the play-by-play. Here’s Bill Buckner hitting off of Steve Carlton, okay, one at-bat, mark it down, one at-bat. It took us a complete winter to build the pace. I always believed in it, I always knew it had value, I sold it to the hitting and pitching coach, that this does have value.

Now, years later, suddenly the game changes and becomes far more computerized. The IT department – which did not exist when I started – suddenly was one of the most important departments in the sport because, without that, you were sitting with a blank screen and without the ability to really develop anything. Then, as it started to really take off in the last eight to ten years, I still used it.

I had a staff of five. The staffs now are much, much greater. But I had a staff of five that were graduates of some of the best schools in the country for economics and for statistics and for math, who loved baseball and who could put things together. I needed it to be succinct and I needed it to tell me a story, and I saw it and I think every leader does this.

I don’t think there’s one team that’s all analytical and I don’t think there’s one team that’s all scout driven. I think the best are combinations of both. Almost equal combinations of both, but probably one shades over the other a touch. I did shade over to the scouting side over the analytical side simply because I believed you need to know who was inside that uniform. How do they think? How do they prepare? What’s he willing to sacrifice? How are they in the heat of the moment? How are they in defeat? How are they in victory?

There are so many different things that when you get down to September, and I’ve been through – I just finished 36 years, I finished the book with 33, that’s a lot of pennant races that’s a lot of postseasons that’s a lot of players that sometimes exceed expectations and sometimes never make it. And really, it’s not injury, it’s really because of who’s inside the uniform. Stats are not going to necessarily tell you that until it’s too late. So it’s a combination for me.

MMO: What did you see in a guy like Justin Turner to sign him to a minor league deal in 2014?

Ned: What I saw in Justin Turner was a couple of things. A couple of things I did see and a couple of things I did not see. I did not see him being as good a defensive player as he turned into. I thought he was a little bit out of shape, but I knew he could hit. The year before we had three great extra players in Skip Schumaker, Nick Punto and Jerry Hairston Jr. Jerry was retiring, Nick and Skip were looking for two-year deals, [and] I wasn’t comfortable doing that even though I loved those guys. I had to go out and find somebody else.

I knew he [Turner] was from the Long Beach area so I knew he had a feel for what a Dodger meant. I knew he could hit and we signed him here late. I signed him here really to play some second base and some third base. If you look back at his career, the first month he played in the big leagues for us was not good. It might’ve been .200 or below that he hit.

I would never sit in the clubhouse and wait for a player; I kind of knew their routines so I would make an effort to run into them so to speak. I waited for Justin one day a little bit and I saw him coming through and knew what direction he was going to head and I went in the same direction. I grabbed him for a second and said, ‘Hey JT, you’ve got to be better than this. This isn’t you. I don’t know if you’re going through a tough acclimation process here and trying to fit in, but you’re better than this. You’ve got to turn it around because I paid you a million. I will release you if I have to. But I need better out of you because I know there’s better in you.’

From that day on, his offense really started to pick up. Then in the wintertime he started to really work on his craft. Brandon McDaniel, who’s a strength and conditioning coach with the Dodgers, moved from Arizona to Southern California to work with players, including Justin. And Justin Turner, I think his career took off by his workouts and his dedication to his craft in the offseason. Particularly the offseason of 2014 to 2015. And now he’s one of the leaders of the club and he’s a great guy, a fan favorite.

He was non-tendered and he signed a minor league deal because of his knee. I gave him a major league offer, he did a physical and his knee showed some issues for us. I gave him a minor league deal and he was a little bit upset with that. I said, ‘Are you healthy? Can you play?’

He said, “Absolutely.”

I said, ‘Then take the minor league deal. You’re going to make the team, I just got to make sure that you are healthy. But your knee can hold up and you will make the team if you are [healthy]. If you are who you say you are you’re making the team.’

And he did.

MMO: You detail the transition of Kenley Jansen from a catching prospect to a relief pitcher. What types of decision-making went into turning Jansen into a reliever?

Ned: I had De Jon Watson replace Terry Collins as minor league player development, and every spring we would meet. I would say, ‘Remember guys, if you’ve got a player that’s got one really good tool, maybe two, but you don’t see him as a big-league player at the position we’ve got him at, be creative and let your mind wander and let me know what you think.’

They came to me halfway through that season and said we’re thinking about Kenley. Nobody thought he would hit in the big leagues. Long arms, long swing, didn’t ever think he’d hit in the big leagues. But he could throw and he had a bit of an aptitude for pitching because he caught. De Jon went to him in about June and talked to him, and he wanted no part of it. He was going to be a big-league catcher.

I went and saw him and said, ‘Kenley, I don’t see it. You are not going to hit enough to be a big-league catcher. Can you catch? Yes. Can you throw? Yes. You understand pitching? Yes. Can you hit? No. You’re not going to be able to hit in the big leagues.’

Little by little he bought in and we put him on the mound and he pitched a little bit in the instructional league and then in the fall league, and he might’ve touched A-ball that first year. We were taking a chance that he could do it. Kenley’s stride off the rubber is probably as lengthy as anyone in baseball today. We saw him and he walked some guys but he had good stuff and a feel for it. So, we put him on the roster with little professional pitching on his resume. Then he went to work in the winter, and he went to work in the spring. And within a year of going to the mound, he was in the big leagues.

MMO: When you look back on your career, what would say are the best trade(s) you made?

Ned: Three that stand out that helped change the room for the positive. One was acquiring Andre Ethier for Milton Bradley within days of me arriving here. Having worked in San Francisco, I knew Bradley and the Dodgers had a tough year together. One of the first things Frank [McCourt] told me was Milton Bradley would have to get traded. I tried to trade him and I could only find one taker, I found Billy [Beane] up in Oakland who would take him.

Al LaMacchia, who’s deceased now, an older scout at that point, I said, ‘I need someone out of the Oakland organization. And I’m hearing this young outfielder named Andre Ethier.’

And LaMacchia’s eyes lit up and said, “Andre Ethier? Take nobody else, Andre Ethier’s the man!”

He was the Texas League MVP, he played Double-A, and he was in the fall league that year, the fall league of 2005. He was in the fall league and the fall league is comprised of five major league teams for one team. And he played on the same team as the Dodgers’ players played.

Our scouts had seen a lot of him, the scouts that went to so our own guys’ play went to see him. And again, this is before I’m even hired, this is when the team is minus a general manager. I just held out for him and we were able to get him from Billy for Milton. He’s still looking for a job but he played his last game perhaps with the Dodgers this past year, 12 years later, so it worked out pretty good.

Next deal is probably Manny Ramirez, July 31, 2008. We got Manny Ramirez for Bryan Morris and Andy LaRoche. We were in the financial straits that we were in so Boston also paid us $7.5 million-plus Manny Ramirez. Manny hit 17 home runs and drove in 53. In a two-month period of time, he hit .390 and really changed the culture of our team from a really good team that didn’t know if it could be really good, to a team that got to the LCS in back-to-back years. The Manny trade was huge, it kind of rejuvenated the franchise.

The last trade was probably the Red Sox trade where we acquired [Adrian] Gonzalez, [Carl] Crawford, [Josh] Beckett, and [Nick] Punto, and paid $250 million to do so. It’s a different-looking trade without the background attached to it. And the background attached to it is we had just gone through the divorce and the bankruptcy, we had drawn fewer than three million people the year before for the first time in decades. Our brand was suffering, and Guggenheim and Stan Kasten says, “Think about the players you always liked. Think about the guys you think can make a difference and let’s see if we can go and get them now.”

We thought Adrian Gonzalez would be a great Dodger, a guy that hit right in the middle of the order. We had a first baseman in James Loney, from time to time a run producer but time from time, not a run producer. We had a chance to help Boston out because they were going through a tough time, they were finishing last and they needed to clean out their clubhouse. They had a lot of guys that had fallen out of favor, including a couple that we acquired, but guys were starting fresh with us.

We also needed to reestablish our brand. I think when you wake up one morning and you’re a great Dodger fan, and you see that they just made this deal with Boston and paid $250 million when the previous ownership wasn’t spending anything, and you get Gonzalez, Beckett – who was useful, and Crawford – who was useful. They weren’t as good as when they were signed by Theo [Epstein], they weren’t the players he had signed but they were still somewhat helpful from time to time. But the key guy without question was Adrian Gonzalez.

That helped set forth a TV deal that fall of historic financial proportions. So one thing leads to another, when you’re doing deals from time to time we need a shortstop they need a second baseman. We have two second basemen they have two shortstops, let’s just go do the deal. That happens once in a while. Many times a franchise, like ours, there were other things that played a role in it. In the Boston deal, it was more than just trying to pick up $250 million and Adrian Gonzalez.

It was trying to pick up a player that was going to be a great Dodger, and a Mexican-American player no less. We have a lot of great Hispanic fans in our market, that was huge. He could change our lineup in a heartbeat, a really good fielder. Also, the fans had gone away, but they came back and bought into the new owners. They thought these guys are back and they’re spending money, they’re building a good team.

When Guggenheim came in on May 1, 2012, from July on here’s who we acquired: Hanley Ramirez, Shane Victorino, Brandon League, Joe Blanton, Adrian Gonzalez, Josh Beckett, Carl Crawford and Nick Punto. We went from not really having a chance to compete, to being eliminated the next to the last day of the season from a playoff spot. And it was a little crazy, I’ll grant you that.

People said, “You’ve messed up the chemistry; you’ve got too many players that are new players.” Nobody we brought in was a detriment to chemistry or a detriment to the organization. Was it a lot of players? Yes. But, we also started that year with a payroll of $90 million. Our payroll was commensurate with a payroll of Kansas City or a Minnesota. With all due respect, our market is much greater than those markets. Our attendance, except when it dipped that year, was so robust in comparison to those markets. We needed a bigger payroll.

MMO: I found it interesting when you talked about the international market in your book. When you first were hired, you write that the Dodgers were virtually non-existent in Latin America, where the buscones wouldn’t even bring their players to your academy. How important is investing in the international market, and what led up to the Dodgers eventually digging deep into Yasiel Puig?

Ned: A couple of things about this. One of them is it’s attached, the thought process and the philosophy is attached to the same thing we did in Boston later that year. And here’s how. You’re right, as laid out in the book, we could not get anyone to come to our academy. One year, we spent less than $200K on signing bonuses for everybody. I was blessed to have only one year as a GM where we were in the sell mode, it was the year I traded Rafael Furcal to the Cardinals. Every other year, in July, I would be looking to add veteran players.

That particular July gave me my first opportunity to really dive into other teams’ farm systems. And the contending teams had so many players from Latin America. Those teams were Texas, the Yankees; the teams that were good back in that period of time. They had a lot of players who had been signed as international signs, and we hadn’t been doing that. I knew we were up against it, I knew we had fallen behind because that’s not a market that you typically sign and harvest a player the next year. You sign a player at 16-years-old, that might take 7-8 years to get to the big leagues.

So we were falling so far behind, and I went to Guggenheim again and they said, “What’s the first thing we need to do?”

I said, ‘Latin America,’ in a heartbeat. ‘We have to be there today because we’ve fallen so far behind. Nobody believes we’re a player anymore, no one believes that we’re spending any money there. Our academy is starting to get a little bit rundown, and we’re losing players. We’re going to pay for losing players for years because it takes time to rebuild that program.’

They asked, “Who do you have in mind?”

The Cubs, if you remember, signed Jorge Soler, he’s now with the Royals. I was at a coffee shop in Seattle and we were playing the Mariners Sunday afternoon and I stopped for breakfast with a friend. And Barry Praver, who was a representative to Soler calls me, and before he could say anything I left the restaurant and went out to the street and told him what I was going to offer him. He was blown away, but he had also agreed to a deal with the Cubs.

I learned how they talked, the cadence in their voice, the anxiety sometimes, you learn to figure out who’s who and how they think, and how they’re negotiating. I could tell with Barry, I have known Barry a long time, that we had struck a chord with the offer. That it was a legitimate offer and may have been a better offer than the one he had just agreed to with the Cubs. We missed him by a day or so, which was okay. I knew we were in business, even though we didn’t sign Soler.

Then something interesting happens. Logan White gets a call from an agent, I get a call from an agent, two different agents, about Yasiel Puig. The agent tells me, “If you liked Soler, you’re going to love Yasiel Puig.”

I asked where we could see him, and they tell me Mexico. I go through that, we sent Logan, Mike Brito, and a couple of other scouts down there, and you’re watching Puig work out, you’re not watching him play games. You’re watching him run, throw, moving from place to place because people are looking to catch up with him for one reason or another. We ended up signing him.

He came to Arizona in June of 2012, worked his way through rookie ball and a touch of the California League, and then went to winter ball in Puerto Rico. He came to spring training and lit it up. He still had a lot of rough edges but the long story short was when we signed Yasiel Puig for $42 million, part of it was for the talent of Yasiel Puig a lot of it was also for the Latin program that had been dormant. We needed to bring life back to it, and it allowed us to show that we were back in business almost immediately.

We had buscones calling us that players will work out for us, literally overnight it changed our standing in Latin America, and we had to do that.

MMO: It was essentially a big statement move for your organization.

Ned: Yes, as was the Gonzalez move. Gonzalez and the Red Sox brought us a really good player and guys that were contributing. Beckett threw a no-hitter for us and pitched well for us. Punto played great being the extra man that he was. But it also brought a statement to it that this ownership was real.

It also brought a statement to the TV markets that the Dodgers were real. Hence an $8.35 billion deal, a year earlier Frank had a $3 billion deal. A year later Guggenheim has an $8.35 billion deal, that’s $5.35 more billion dollars a year later. Did the Gonzalez deal do that? No. But, the Gonzalez deal probably helped a little bit. And just the philosophy that this team was real this organization was real, ownership was real, and we were going to do big things, which they have.

That brought that revenue to that record level and then the Puig thing was kind of in the same way. We needed to restart Latin America and we did it with a big signing. Did we overpay? Genuinely, the day we paid him, we thought we may have overpaid. We didn’t know if we overpaid or underpaid, we just knew we needed to sign him. Otherwise, the market was going to continue to lay dormant, and we signed him right before July 2.

So, not only did we sign him, and give notice when we did, but also because July 2 is signing day for other players in that region, we were able to capitalize a little on that, too. A couple of weeks after we signed Puig we signed another guy down there who’s going to be a really good one, a little bit of an injury lately, but we also signed Julio Urias.

MMO: That’s right, out of Mexico.

Ned: Yes, on the same trip. On the same trip we saw him and signed him later, and a couple of weeks before we signed Puig we drafted a kid named Corey Seager. 2012 was an amazing year for this organization. Didn’t turn out to be a playoff team, but it put many things in place that fueled this team victory wise, fueled it Division Championship wise, LCS wise, chance to play in the Fall Classic last year, and also a financial boom when it comes to the TV deal and the revenue of the stadium.

MMO: I can’t thank you enough for your time today, Mr. Colletti. Thank you for such an in-depth and behind-the-scenes look at the life of a general manager.

Ned: I appreciate your time. Thank you.

Follow Ned Colletti on Twitter, @realnedcolletti

Check out Colletti’s book, “The Big Chair: The Smooth Hops and Bad Bounces from the Inside World of the Acclaimed Los Angeles Dodgers General Manager“.