Collegiate Baseball Newspaper

The name Perry Husband might not resonate with most fans of Major League Baseball.

But it should.

Husband, 56, is a pioneer when it comes to baseball science. He developed a theory called Effective Velocity, which is the study of pitch speeds and how location changes the reaction time for hitters.

Response time is key to understanding the basis of Effective Velocity, or EV for short. A bat must move farther to reach pitches on the inner half of the plate compared to the outer part as a batter can wait to hit an outside fastball as it crosses the plate. An inside fastball requires the hitter to move the bat a greater distance in less amount of time. For example, if a pitcher throws a 90 mph fastball on the outside part of the plate, Husband calculates that it would actually appear to be in the mid-to-upper eighties as opposed to an inside fastball which would increase the EV speed closer to the mid-nineties.

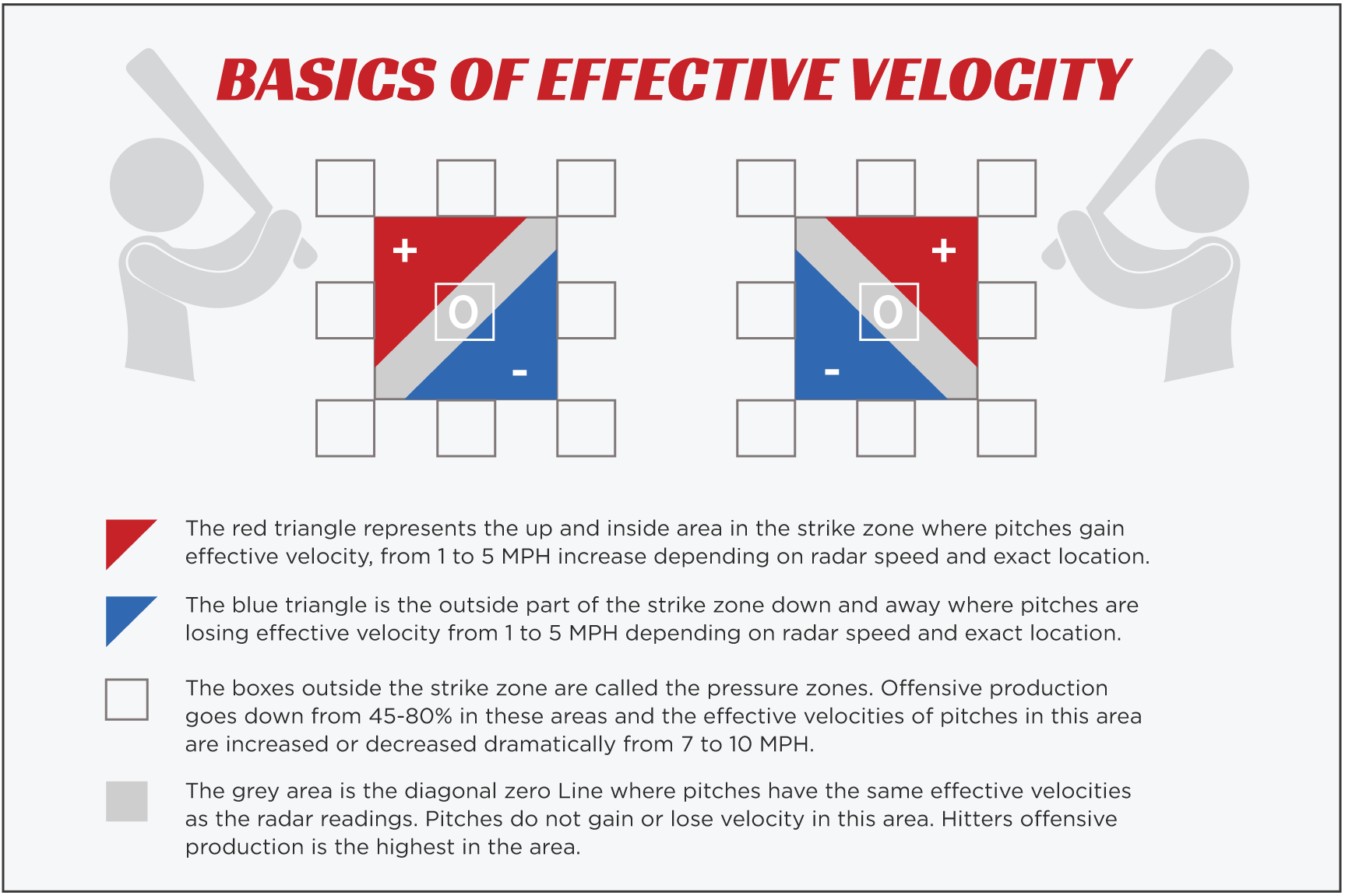

The chart below illustrates Husband’s concept of EV. Pitches in the red triangle (inner part) are where pitches gain in effective velocity and the blue (outside) is where pitches EV. Of course, the concept of EV is better utilized in a sequence rather than a single pitch. A hitter’s perception of a pitch is predicated off the speed and location of a pitch(es) before, meaning the perceived velocity of a pitch can appear even faster or slower depending on what pitch it follows.

Chart from SB Nation

A former sixteenth-round pick of the Minnesota Twins in 1984, Husband’s career spanned two seasons in the Twins’ lower levels as a second baseman before he was released. At 24, Husband began coaching and eventually opened up his own academy in Quartz Hill, California. While instructing kids in hitting lessons, he would routinely tell them where the pitch would be, to help build confidence and improve timing. It was there that Husband had one of his first “aha” moments when he noticed that his pupils were late to pitches, even after warning them of the location.

His curiosity was more than piqued.

To further his research, Husband enlisted his friend and former teammate while in the Twins organization, Jay Bell, to help test his theories. Bell was tasked with hitting balls both off a tee and during live batting practice and was asked to hit a target that was in straightaway center field. Out of thirty swings, Bell connected to center only three times with most of the batted balls pulled to left.

The results of the test indicated to Husband that hitting even stationary balls to specific targets is extremely difficult, with a certain amount of luck being heavily involved and hitters often succeeding off of pitchers’ mistakes.

According to Husband, the drills he performed with Bell back in 2000 were the first publicly known exercise that dealt with two major modern metrics that are heavily utilized in today’s game: exit velocity and launch angle.

A term fans might have stumbled upon when viewing clips of pitching overlays featuring how well a pitcher hid two different pitches is a term Husband refers to as tunneling. When two different pitches – normally a fastball and off-speed pitch – starts out in the same horizontal and vertical planes together for at least twenty feet, it significantly reduces the chances of solid contact. If pitches stay in an EV tunnel for halfway or more to the plate, it makes it virtually impossible for hitters to properly react to the pitch.

Carlos Pena, the current MLB Network analyst, was a disciple of Husband’s back in 2009. Husband was tasked with formulating game plans for Pena against individual pitchers using the EV methodology. The slugging first baseman for the Tampa Bay Rays bought in and was co-American League home run champion that year with Mark Teixeira (39 homers).

As an analyst on MLB Network, Pena regularly adduces EV and Husband’s philosophies, noting how the next frontier in Major League Baseball might be Liquid Analytics. This form of analytics looks at the here and now – aligning with Husband’s work – with the ability to impact games in the moment. Husband opines that today’s analytics are historical, comparing it to a photograph stuck in time.

Rather than utilize these forms of analytics, Pena and Husband both are of the mindset that Liquid Analytics will propel teams to even greater success at it focuses squarely on real moment data.

I had the privilege of speaking with Husband for an in-depth interview, where we discussed his theories and studies of EV, where he sees liquid analytics fitting into today’s game and information on Jacob deGrom.

MMO: Effective Velocity is a term some ardent fans might have heard while watching Carlos Pena on MLB Network. For those who haven’t, can you explain your theory of Effective Velocity?

Husband: On the very core surface of it, Effective Velocity is the study of pitch speeds. If you throw 95 – the average pitcher today in the big leagues throws 93 mph – but when they throw that pitch middle-away, it has a different reaction time because the hitter has a longer time to reach it. It’s really closer to about 90 on the outside part of the plate and on the inside part of the plate, it’s closer to about 95.5.

Every six inches of change in the strike zone is going to change the hitters’ reach pretty dramatically. Every time you move the ball around within that area that the hitter can reach it’s going to change the speed of the pitch, and that does a number of things. It explains a whole lot about why certain hitters on one day are gangbusters and the next day struggle because at the end of the day pitchers are either using speed well or they’re not. It’s kind of like time and money for a businessman; speed and deception are what the pitcher has to work with. They’re either making it very obvious for hitters to see pitches and then they’re using their speed efficiently or they’re doing the opposite; like in the case of a lot of different guys in the course of this last postseason.

When you throw fastballs away, like Clayton Kershaw, if he’s at 91 to 93 but he’s living at the bottom part of the strike zone, the reality is that he’s throwing his fastball at about 89 average EV. If he throws his fastball in the bottom of the strike zone and then he comes back with a slider anywhere in the strike zone, the slider is actually going to have a faster effect than his fastball is when they’re that close in speed. It explains why a guy like him, who’s been unbelievably great for a long period of time, all of a sudden is not great. He’s lost a couple of mph but he’s also lost effective mph because he’s not hiding the fastball and the slider coming out of the same Effective Velocity tunnel.

That’s one of the other major discoveries with Effective Velocity is that when pitchers know what they’re doing, the fastball creates a line when it comes out of the pitcher’s hand. For example, if he throws that fastball at the bottom of the strike zone, picture a fastball coming out of the hand and making somewhat of a straight line down to the bottom of the strike zone, it’s going downwards. When he throws his slider – if it’s going to be in the top part of the strike zone – would have an extremely different look out of the pitcher’s hand.

The only chance he has at making those two pitches look-alike is if he throws the fastball at the bottom of the zone. The only place that slider can hide is below the strike zone and it looks the same for twenty feet out of the pitcher’s hand and then the ball disappears out of the bottom of the strike zone. That’s when he creates his Effective Velocity tunnels and when that happens he has a lot of success. When he doesn’t create those tunnels and pitches look different to hitters and they’re close in speed, he has a tough time succeeding.

MMO: Is there a specific distance between the pitcher and hitter where once it reaches that said point it makes it that much tougher on the hitter to pick up?

Husband: There’s kind of a couple of different things that are important about that. I did a crazy amount of studies. We studied hitters to find out what it is they could see and what point they could hit it. Every hitter from 10-years-old to the big leagues can tell whether the ball is going up, down, in, or out of the pitcher’s hand within about five to ten feet. The first thing they see out of your hand is the direction that the ball is going and obviously that is altered a little bit if you have movement, but in general, they can see where the ball is going.

Towards the end of that twenty feet, they start to recognize spin. If you throw two pitches and they look alike out of the hand, they’re coming down the same tunnel, and if one of them has a slightly different spin – like a slider or a cutter or something that would look a little bit different than a four-seam fastball – then the hitter starts to recognize it at about the twenty-foot mark.

The average pitcher is going to let go of the ball somewhere around fifty-four feet in front of the rubber. At fifty-four feet divided by three areas you basically have eighteen feet for the third of the pitch flight. The first third is where they recognize the simple stuff like where it’s going and if the ball is going to look different. In that second eighteen feet is when they start to recognize the speed and they start to recognize the spin, which will tell them pitch type. Then it takes the whole last third for the hitter to swing the bat and they’re limited by human reaction time. That human reaction time is one-third of the flight. So they have one-third of the flight to pick up the easy stuff and then they have a third of the flight to pick up the really difficult stuff.

If the pitcher throws pitches that look alike in that first third for eighteen to twenty feet, that is really difficult for hitters to be able to recognize what the speed of the pitch is. When you see on Twitter all the overlays that are happening now, you see how poorly hitters react to those pitches. They look terrible on the sliders; they’ll swing at sliders in the other batter’s box if they started in a tunnel that looks like a fastball.

It’s really difficult for hitters to do anything if the pitch fools them for the first third of the flight.

MMO: Each pitch is predicated off the last one thrown. Can you explain your concept of an at-risk pitch?

Husband: Carlos Pena is a former client and he is an MLB Network analyst now. Last year before the postseason started we did a prediction and basically, soft contact happens in all kinds of random ways. Guys can get pitches right down the middle and there’s a seventy percent fail rate even if you throw pitches right down the middle. There’s a little bit of random stuff that goes on with soft contact and strikeouts. But when it comes to hard contact it happens exactly the same way.

We predicted that fifty percent of all the hard-hit balls that would take place last postseason would happen within six EV mph of the last pitch. If a pitcher is throwing 93 but he’s really throwing it middle away, it’s closer to 90. If he throws his slider at 88 and it’s a little bit middle-in, that slider becomes 91. If that ball is hit hard it’s within six EV miles of the last pitch. So even if they’re different pitch types – if they’re close in speed like a player going to the batting cage – you see one after another after another and you use it to time it. Fifty percent of all hard-hit balls happen from that way.

Twenty percent happens when you create no tunnel. In other words, you make the recognition for the hitter easier. Then 20 percent happens when you throw pitches in what’s called a hitter’s attention. A hitter goes to the plate expecting a speed, expecting a pitch type, expecting an area, and typically it’s fastball away because that’s where pitchers have lived for one hundred years. Every pitch that’s thrown in that hitter’s attention zone there’s about a six mph zone that hitters react to the best within that speed range. So every pitch that’s thrown in is automatically at risk.

For Clayton Kershaw or anybody who’s throwing 93, anything from 90 down to about 85 is in serious trouble because that’s the speed that the hitter focuses on and that’s the area that they’re the most prepared to hit. Anything within those three basic categories makes up 90 percent of all the hard-hit balls that took place last year in the postseason.

The last way is when a pitcher throws a pitch out of an EV tunnel and that pitch has six mph or more between it from an EV perspective, only ten percent of those balls happen that way. It’s always been that way.

MMO: How did you land on the six mph number?

Husband: Because of a bunch of studies. I did a ridiculous amount of testing of hitter’s reactionary times. The current Red Sox’ hitting coach, Tim Hyers, he and I in about 2006 did a test with 192 Perfect Game elite high school athletes. We did a reactionary test. In fact, it’s the only one I’ve ever heard of anybody doing at least publicly.

We tested players to find out what they could and couldn’t react to. They got eight swings and in the eight swings it was kind of like a warm-up; we focused on pitches they would expect. They got middle fastballs and middle-away fastballs. We kind of geared their mind to that. We didn’t pick 90 or 80 mph like they would see in regular games, we picked 70 so that there were no questions about the validity of it.

After the eight we then threw them eight pitches that counted in the test. It was thrown from a pitching machine that has the ability to pinpoint pitches. And every pitch was within one mph of seventy. Then we moved the ball middle-in, up-and-in, and down-and-away because each time you move the ball in the strike zone you change reaction time a little bit. What happened is on average these players were early, late, on time, but they only squared up one and a half balls out of eight, which is equivalent to about a .187 hard-hit ball rate. And they broke every wooden bat that we had before the test was done! [Laughs.]

Just taking fastballs and moving it around the strike zone you’re going to change the speed somewhere around or up to – if they’re throwing a major-league fastball – it changes the reaction time by up to ten mph.

That’s one way that you can test it. In fact, it’s the best way by using one speed but move it around in the strike zone, and what you’ll find is the same thing happens. Guys are early and late even when you have zero mph of speed differential. All of my initial tests showed that hitters had about five mph of reactionary time where they could actually adjust to a pitch and hit it close to their max. But as soon as we got out of that five mph that wasn’t happening. They would mishit it, be early, late; that’s where the initial six mph came from was through that testing.

Back in I believe 2002 I took it to Inside Edge, which at that time was the only company that had a database of pitches with pitch speeds and locations and they were the only scouting company in the business at that point. They opened up their computers to me and allowed me to start studying to see if the same things were happening at the big league level that was happening with my studies. We taught the computer how to look at a 93 mph fastball away differently, in other words, they added or subtracted the actual EV speeds. And in doing that we looked at 330,000 pitches and the only reason that was the number was because they had about 5 million in the database but not all of them had speeds. We had to have exact speeds and exact locations in order to be able to do the test accurately.

What the database showed – and we predicted this ahead of time – knowing where the science was going to lead if I was right then there would be one EV mph speed that hitters would tend to really hit hard. We looked at hard-hit ball rate, home run percentage, and batting average which ties to hard-hit ball rate. They’re not exact, it’s what everyone expects, so we threw that one in. We looked at swing and miss rate because all of those are timing-based. In other words, if hitters are on time then they don’t swing and miss. The swing and miss rate dramatically changes when they’re on time for a pitch.

Those key statistics – every single one of them – peaked at exactly the same EV mph over those 330,000 pitches. Which means hitters basically are geared to 90 EV mph. At 90 EV mph, home run percentage was the highest, batting average was the highest, hard-hit rate was the highest, and the swing and miss percentage were the lowest. Three mph on either side of that peak and the numbers dropped off pretty dramatically.

Not only did our tests prove that the mph was about six that they could handle, but so did the statistics. The statistics showed that outside of that six mph, hitter’s abilities to react to pitches dropped off. When you look at through an EV tunnel and beyond six mph, hitters are very poor when they start to see pitches that are difficult to see in the initial 20 feet. And some pitchers throw pitches that are in that tunnel for well beyond halfway to the plate. There are certain pitchers that when they throw a combination of pitches it’s beyond the point where hitters can actually react to it. By the time they recognize what pitch it is, it’s already too late for the fastball and it’s too late for them to adjust to any type of off-speed pitch.

MMO: How and when did you come to discover the theory of Effective Velocity?

Husband: It started in probably the very early nineties. I started a little baseball school and there were a million “aha” moments that led up to Effective Velocity. But little things like having hitters – throwing four or five fastballs away – know it’s coming and they’re geared to it and they hit it pretty well. Then you throw a fastball in and you tell them that you’re throwing a fastball in but they’re late and then you tell them again, ‘No, really, here comes a fastball in,’ and they’re still late!

I started thinking, There’s something weird going on because I’m telling them what’s coming and yet they’re still late. There’s got to be something more to it than just the fact that I’m moving the ball in and out. There were a bunch of little “aha” moments leading up to a few really big ones.

One day I was watching A-Rod hit a homer, it was a 96 mph fastball down and away. He hits this pitch and he looks up to the left-field bleachers because he knows he hit well. After a couple of seconds of looking at left field you see him move his head around and finds the ball in right field. And I thought, Wait a second. He was pretty sure he pulled that pitch, and yet that ball went to right field out of the yard!

In essence, he didn’t really hit that; the pitcher more realistically hit his bat. I started wondering how often that happened and that was one of those moments it was very obvious that there was something weird going on in the big league level that matched the stuff that I kept finding in my academy.

MMO: In the biography on your website it states that two other modern metrics that you introduced to baseball were exit velocity and launch angle. When was it that you started studying those two metrics, and did it coincide with your work with Jay Bell?

Husband: Yeah, actually in 2000 we did this test with Jay Bell. He and I were roommates in the minor leagues and I asked him to do me a favor because I had done a lot with kids. I had a really good idea of what was going to happen but we did a before and after test with his swing. We did two phases with it: a tee test and a live-pitch batting practice type of setting. We did it in a way where we could measure what was happening off the bat. We would videotape the whole thing and then put it into at that point a VHS.

After we looked at the first test we’d set up a target and on the tee test, the target was set up so that if you were to hit it perfectly, the ball would travel fifty feet and hit into an area that was about the size of the strike zone. If he were to pull the ball a little bit less we’d know that he was a little bit early off the tee because the tee is just sitting there. So there is timing involved; it’s just one timing, there’s no adjusting to the timing.

In the first round, he hit three balls out of ten in the middle, which is three out of thirty that were perfect. Then he had eight balls that missed the target and the bulk of the balls were kind of hit down in left. I started looking at it from the perspective as a golfer would. I spent some time after getting out of baseball as a golf pro instructor and the exactness of golf was something I saw as sorely missing in teaching hitting.

When I went back into teaching hitting I looked at it very differently. If you put an exact target with any hitter anywhere, they’re going to hit the target a certain amount of times but they’re also going to miss it a huge percentage of the time. And by missing it I mean they’ll be underneath the ball, a little above the ball, they’ll pull it left or right. When you start getting that exact, when you start really looking at precision, then it starts to open up a whole other can of worms. Now you realize what’s really going on and it’s super complex when you talk about all the factors that go into it.

The launch angle was something that when you hit it perfectly it’s around ten degrees. When he [Bell] missed it, if he were to hit it absolutely perfect and straight off the tee, it would be a ball that was going to end up at zero degrees. If he hit at the top of the target it would’ve been at about twenty degrees. Everything that we initially did we found out that any ball within ten degrees of the target he’s trying to swing at, he was at his maximum exit velocity. But as soon as he got outside of that ten degrees the exit velocity started to go down because the ball was deflecting off the bat a little bit more and a little bit more and a little bit more.

The further away you get from hitting the exact center of the ball with the exact center of the bat, as soon as you get away from that you start to lose exit velocity dramatically. It lends itself immediately into understanding what happens when you start fooling hitters with EV tunnels and use speeds that they can’t quite recognize. Now you’re forcing contact to happen off the center and then you’re controlling the exit velocity off the bat. They’re extremely closely related. One led to the other in the sense that without understanding exit velocity and putting a measurement to it, and without understanding launch angle and putting a measurement to that, you really can’t measure hitting.

I used to get into arguments all the time and it was so ridiculous because even to this day hitters and coaches will argue about hitting styles. For me, it was all about putting that stuff to rest. If you test it then you shouldn’t argue anymore because it’s a simple matter of you think that getting your elbow up is the best thing and you were a bug squisher, and you think that those mechanics are the best. I started using exit velocity because it was a way to disprove the guys that I felt like we were on the wrong track with some of the things they were teaching. That was the point of it initially, to kind of prove that the mechanical stuff I was talking about was on the money.

By the way, we added 10 mph to Jay’s swing in about thirty minutes. We changed his launch angle in what would be considered to be an average of about a minus five degrees to a positive ten degrees in that short period of time.

MMO: And as far you know, you’re the first to test for launch angle and exit velocity?

Husband: Publicly for sure because no one had done anything publicly. I don’t know, there might be some people out there that were doing some stuff but as far as I know, that was the very first test using exit velocity and launch angle as a way to kind of reverse engineer the swing to find out what happened.

That’s what you do in golf. When a ball is hit there are only nine possibilities of the direction that the ball can go and depending on what the club head is doing on impact you don’t even have to actually look at the player; you can just watch the ball and then reverse engineer what’s going on in the swing to cause that. That was kind of the basis for looking behind exit velocity because it was the one way that we could make it like a golf swing. In order to look at the precision of it and to be able to measure that you have to get kind of anal. You have to look really closely at extreme details; without a measurement it’s pointless.

MMO: You worked with Carlos Pena in 2009. How did that relationship start and what would you work on specifically to help him grasp the concepts of EV?

Husband: Effective Velocity is like math. Can you learn math in one day? The answer is, no. You can learn addition or subtraction or maybe even addition or subtraction. And maybe addition, subtraction, multiplication and then division. But you’re not going to learn math in one day and Effective Velocity is very complex because there are a lot of factors.

The way it started with Carlos was he had heard about my work a year earlier, but he hadn’t really started struggling until midway through 2009. Pitchers started to realize that if they elevated their fastballs he was having a tough time with that. He just didn’t react very well to that because his swing was geared to fastballs away because that’s where guys had lived. He had started to struggle a little bit and he called me and we started talking and I was trying to explain to him about the fact that hitters really have no chance if they’re trying to react to pitches. If you really want to have a leg up you have to act versus react instead of waiting for pitches to show themselves.

My studies show that you can’t do it, you literally just can’t do it. You can’t wait to see the pitch and then have a chance to react to it and hit it anywhere near your maximum output. His initial response was, “I’ve always been a see it and hit it guy and I’m very uncomfortable thinking about the idea of sitting on a pitch, like guessing.”

I said, ‘I did a little research, and would you agree with me that 0-2 and 1-2 counts are the most reactionary counts? You’re in a hole and now and you have to see it and hit it.’

He said, “Yes.”

I said, ‘Your batting average right now is .085 in those counts and you’re leading the league in strikeouts. My question to you is, what do you have to lose? You’re not going to strike out more and you’re not going to do worse than .085 so realistically what do you have to lose?’

I left him with, ‘You’re going to face the White Sox tonight. Bobby Jenks is likely to close so you may get an at-bat against him. Here’s what I’m talking about in general; have you ever done anything against him?’

He said, “No, I totally struggle against him.”

I told him, ‘When he throws 98 some different things happen to his ball. Number one, it doesn’t sink as much as other pitches. Number two, because of the fact that you crush balls away, in your mind his 98 fastball equals 95. But in reality, he’s not going to locate it down and away, he’s going to locate it at the top of the strike zone so it’s really closer to 103-104. If you’re not thinking like 110 then you are going to have a very tough time with him. If you add that six mph to him – the effective speed – and you try to miss the ball over-top I think you’ll actually have a chance to do some damage against him.’

He calls me the next day and said, “Hey, did you see the game?”

I told him, ‘No, I didn’t see it. What happened?’

He goes, “I got an at-bat against Jenks and I don’t know why I decided to try it. I hadn’t had any success so I just decided to give it a shot with what you’re talking about. We had a guy at third and I hit a scoring fly ball and we won the ballgame. But I broke my bat so even though I was thinking 110 I was late because I broke my bat; I hit it off the handle a little bit. And because I hit a fly ball even though I was trying to get on top of it, I didn’t. I was still underneath it in order to hit the flyball. Now I know that you know what you’re talking about. Now for the first time, I know what timing really means.”

That’s kind of how it started. It took us a week or so to get on the same page and then he hit a homer every eight and a half at-bats over the last half of that season, he was on fire. He missed a month of that season and still tied for the American League lead in homers (39, with Mark Teixeira). He literally was the home run champion with missing a month of the season.

MMO: It seems like he bought in fairly quickly.

Husband: If you spend your life in something like hitting – as I did as a player – there’s so much that you have no idea what’s happening. That’s why so many hitters will look for things like not washing their socks for a month because they feel like it’s lucky. Superstitions happen when you don’t have an explanation when you don’t know what’s happening.

To this day if you ask a big-league player what causes a slump they would tell you those are just going to happen, it’s just part of the game. That was another one of those things where I read an article on slumps, and again they all end exactly the same way: we have no answer for it so it’s just going to be a part of the game forever. I kept thinking No, I know what the answer is and the answer is hitters don’t understand that there are illusions going on and they keep doing the same thing and don’t see a need to make any changes.

With that in mind, that’s why slumps happen; there’s a timing weirdness that goes on like with Jenks and Pena. He would never know that the ball’s beating him because it’s a weird illusion of speed and until you understand how to see through that, that weird illusion is going to win the battle every time. Big league hitters are awesome athletes but they’re trusting their athleticism and it doesn’t work in certain circumstances.

MMO: In an SB Nation article, it details your meeting with the Houston Astros back in 2005 and how you presented some of your theories with the Astros brass. How prevalent would you say your concepts of EV are around the game of baseball today? Are there teams that are utilizing this information more so than others?

Husband: Zero teams are all in, let’s put it that way. Two-thousand five is a really great example because that was one of the starting points. I actually talked to five clubs when I made the discovery of EV, and the first guy I took it to was Barry Zito. He was working with a buddy of mine and I shared some of the discoveries with Effective Velocity with him and he worked with Zito in the offseason and said, “I’d really feel remiss if I didn’t set you guys up and at least talk.”

Zito had started to go a little downhill. He won the Cy Young in ’02, ’03 was really good, and then in ’04, he started to slip. Lefty hitters hit like .330 off of him and the righties had started to figure it out.

I met him before the ’05 season and we spent a lot of time talking about how and why guys were having success. With lefties if you throw fastballs away and a loopy curveball they can see them both; there are no tunnels. In fact, that year lefty hitters hit over .600 on the first pitch against Zito. When you think about that, with a guy that has the best curveball in the business, and yet guys are hitting him at a really high clip because they can recognize it and because even though he had a big speed differential between his pitches when hitters recognize it out of your hand they have a chance to adjust to it.

He was the first guy that I directly introduced it to at the big league level and in the beginning, he didn’t really get it. It was something that was a little bit tough; there’s a learning curve for sure when you’re trying to implement the concepts. It’s a lot easier for a pitcher but if you get it right away the first tendency is if I can add two mph by moving it here or if I move it to the perfect place and add five mph then that’s the place I want to throw it. And then it’s ball one, ball two, and it changes everything. It took him a little bit to get on the right page, but when he did it he just went off.

He was one of the first and then the pitching coach for the Astros that year was Jim Hickey. And he was all in, literally. He was one of the first guys that said, “This is on the money.” I was basically telling teams that I have a secret and it’s pretty good and it would be worth it to you to take a strong look at it, that’s why I met with the Astros and spoke to Andrew Friedman on the phone. At the time he was the Devil Rays’ GM.

Hickey was hired by the Rays and they became a pitching factory, so to speak. Then he went to the Cubs and before they won it [2006] they hired Derek Johnson out of Vanderbilt to be their minor league pitching coordinator. He’s been a long-time EV follower, too. He invited me to speak to the whole minor league coaching staff of the Cubs and so I went over and did a whole demo at their Phoenix spring training facility. He had guys like Kyle Hendricks in the minor leagues at that time. He went from there to the Brewers and all of a sudden even though PECOTA has the Brewers winning 77 games in 2017, they almost shocked everybody with a run towards the end of the season.

Effective velocity is timing. At the core, it’s the metric of timing and deception. Every statistic that has anything to do with a pitcher or hitter, every one of those statistics is timing-based. Analytics has no measure for timing. They look at a fastball that’s fouled off and the hitter is bringing his hands in and fighting to just barely get the bat to the ball or a ball where he is literally extended, you’re right near the barrel and he fouls the ball off, and they look at those exactly the same. From an EV standpoint, they’re miles apart because one of them he’s extremely late and the other is he’s extremely on time and you just dodged a bullet. Whereas the first one you own him and if you know that as a pitcher, now you can work off of that. At the end of the day, that’s what Effective Velocity is.

To answer your question, there are some key teams that have really bought in. But they’ve only bought into the parts they understand. Think about it like EV 101. On the first level – like the tunnels and just the fact that speed changes within the strike zone – if you just understand those two things you’re going to get immediately better as a pitcher. As soon as you start creating tunnels you start making it more difficult for hitters to recognize you. Now you still might not know what you’re doing with these tunnels because you can actually create tunnels that are helping hitters. But if you have an EV 101 understanding of that concept then you’re going to get better as a pitcher. And that’s what some teams have done; they’ve incorporated the easiest parts of EV.

There’s still a lot to be desired when it comes to their understanding of how to sequence and how to maximize their deception and their speed use. As far as that goes, every team in the big leagues has an EV 101 understanding. They understand that there are things that are happening. The top teams have maybe an EV 201, maybe even a 301 understanding. But just like there is in math, there’s a whole lot more they still have to understand before anyone is 100 percent invested in Effective Velocity.

The game is timing and unless the core element you’re invested in is timing, then you’re missing the boat. Analytics is historical; you look at the fact that a guy walked 100 times, that’s great. What caused him to walk 100 times? We don’t know and we don’t care, he walked 100 times, therefore, he’s god. [Laughs.] That’s pretty much how it is and as soon as he stops being god and walking 100 times, we’ll get a new guy that walks 98 times.

Analytics is historical, you’re looking at stats in really cool ways through a bunch of different lenses and it’s all awesome, but it’s historical. It’s like taking a Polaroid of that guy at that moment. Now you have this picture of him and it’s a really cool picture but it’s still a picture that says he had X amount of these, X amount of those, and when you add them all up he’s a good player and this one’s not. At the end of the day though, the second that player changes something, now all of a sudden all of those numbers change.

I’ll give you a great example. I did a little bit of work with Raul Ibanez when he was with the Yankees during his historic run down the stretch. What would an analytics guy say about a 41-year-old player the next season after that? First, having a guy lead the Yankees through the end of the season and then the next year he hits 24 jacks in the first half of the season with the Mariners. Who predicts that from an analytics standpoint? History is going to say not no but hell no is that going to happen! But when you understand some things differently the playing surface changes, and that’s what Effective Velocity is. It changes the game because it focuses on the number one thing in the game.

I was at a SABR convention a couple of years ago and Bill James was being honored and he was speaking to everyone in the audience and he said, “You can spend your life looking at statistics and you can bury yourself in little statistics. You’ll learn some things and answer little questions. But if you want to change the game, if you want to make a difference, you have to ask big questions.”

It struck me that with Effective Velocity I started with the biggest question there is, which is what causes hard-hit balls. When you look at that, it’s the core essence of all hitting and pitching statistics. It all comes down to that moment of perfect contact. And hitters that understand it a little bit better recreate it more often. Pitchers that understand it a little bit better avoid it a little more often than everyone else.

The state of things right now, in my opinion, is that the league basically has a 101 or 201 understanding. There are a lot more levels and a lot more classes that they need to take before they really get it. Ninety percent of all the hard-hit balls are EV 101 mistakes that they’re making that they don’t realize are happening. I’m sure on some level they realize it’s happening but looking at it through one of those historical lenses that analytics provides. They’re looking at it at a season where the thing that matters the most is avoiding hard-hit contact if you’re a pitcher. The way you’re going to do that is not trying to get more ground balls. By getting more ground balls you’re actually creating an atmosphere that’s going to do the opposite.

It’s the weirdest thing ever but if you were to actually do a study of ground ball percentage and you took it to the very end, the end game is that you actually are creating ground balls slightly at a higher percentage but you’re creating them at a higher exit velocity. Even though the whole analytic world hates ground balls and loves them for pitchers, they’re actually completely and utterly misunderstood.

If I just asked you, looking at what everyone says on the Internet, they basically would tell you that even hard-hit ground balls are bad, and so hitting fly balls is everything, right? We’ve been told that for a while. I did a study and the study was I’m going to take only 100 mph ground balls and then I’m going to look at 90 mph fly balls because they’re telling us that all fly balls are better than the ground ball. We all know what’s going to happen to 100 mph fly balls, they’re homers. But the 90 mph fly ball is enough to hit a homer, yet, it also includes popups. When analytics looks at statistics, they typically take popups out and when you take popups out of the mix it’s completely and utterly unfair to the ground ball. You can’t take out dribblers, you count those but you don’t count popups in the home runs and adding line drives into it? They typically put line drives and fly balls together, and against ground balls, they’re going to lose! You take out the worst part and you add in the best part and so fly balls wins the day.

In reality though, when you look at 90 mph fly balls – which is enough to hit a homer – but it includes all the other stuff and the bad stuff, and you compare it to 100 mph ground balls, there was I want to say 225 players that averaged .400 or higher when they hit 100 mph ground balls. Their batting average was .400 or higher, the mean was about .550, and the top guys were about the .700 range. When I look at that I think, Wait a second, I thought all ground balls were bad? The answer is no, 100 mph ground balls are ridiculously good.

Now you look at fly balls and how many guys averaged .400 on the 90 mph fly balls since they’re so much better? Zero. Not a single guy averaged .400. And only ten guys averaged .200 on those fly balls. When you look at the fly balls that are the fly balls, not the homers, the homers are stupid to look at because you hit 100 mph and you hit it up it’s going out. Take those out and look at the actual fly balls that are right at the edge of leaving the yard or not, and ten players hit .200 or higher. The ground balls varied that when you look at the statistics from that perspective. What’s causing those 100 mph ground balls are guys trying to throw ground ball percentage; they’re trying to get ground balls. When you throw fastballs at the bottom of the zone you get ground balls, but you get 100 mph ground balls which are backfiring. But when they hit it square with an upward swing plane and a downward pitch plane, the home run explosion is nothing more than pitchers being stupid and hitting bats.

You’re familiar with Occam’s razor? It’s a science term that basically says you should look at the most obvious answer first because typically that’s going to be the one. It’s not a hard fact of science but it is a good place to start, so they put together a group to look at the reason for all these homers. They looked at the bat and balls, but at the end of the day, it has nothing to do with those things. They concluded that the ball might travel four-six feet further than it did back in the day, but that’s not the answer because there are not that many 90 mph home runs. If there were a boatload of homers that were happening at 90 mph which barely gets it out, then I would say that would be a big factor, but that’s not what was happening. We’re talking about 110 mph homers that were happening and it didn’t matter that extra six feet of flight.

The true reality of it is that analytics caused this. They caused it by trying to create more ground balls. You’re throwing pitches that – like a fastball at the top of the zone at 95 mph – is going to have a two to three-degree downward plane, so it’s almost flat. That same pitch thrown down in the zone is about seven or eight degrees downward. Some pitchers that are taller and don’t throw as hard are going to end up at even ten to twelve degrees downward on the fastball. The average swing in the big leagues is going upwards by about ten or fourteen degrees, so they’re creating this line where you throw a lot of hard off-speed pitches and throwing these fastballs at the bottom of the zone to get ground balls. In reality, what you’re doing is you’re throwing pitches that match everything a hitter is working on. It has nothing to do with the dynamics of the ball being juiced or maybe the guy’s being juiced, I think it’s a lot tougher now to get away with.

In my opinion, it’s that simple Occam’s razor staring us right in the face that pitchers are throwing the ball downhill, hitters are swinging the ball uphill. That sounds like an accident waiting to happen. I can’t even fathom that that’s been allowed to go on for so long with every front office having so many guys and all they do is look at numbers, how do you miss that one? How do you throw pitches that result in 100 mph ground balls and then hate on the ground balls when it’s actually a major factor in everybody’s approach?

Hitters try to eliminate ground balls, they just say no to ground balls and launch angle. But even Josh Donaldson that year saying no to ground balls hit over 40 percent ground balls. There’s a simple fact of round/round contact. When two round things hit each other there are only three possibilities of what’s going to happen. You hit it perfectly, the center hits the center. Or, one center hits below center or above center. Those are the only three kinds of contact that are going to happen.

It’s inevitable that no matter what you do you’re going to hit about 40 percent of the balls that you swing at below, and about 40 percent you’re going to hit above center, resulting in ground balls. And then about 20 percent you’re going to hit close to center on center. When you look at statistics historically, that’s the breakdown in Major League Baseball every year. It’s about 20 percent line drives, fly balls typically 36-37 percent, and ground balls typically 43 percent, somewhere in that range. When we try to eliminate ground balls the number jumped up to 46 percent, so trying to eliminate them actually added 3 or 4 percent to the pot of more ground balls.

You can’t control contact by trying to hit fly balls, it’s ridiculous to think you have that kind of power. That’s why my stuff is called hitting is a guess because it is, on so many levels, and they haven’t even figured out all the levels yet.

MMO: What would you like to see happen next in the evolution of EV? Where do you envision these concepts of EV, tunneling, at-risk, etc. going in Major League Baseball? Could we have radar guns with EV readings?

Husband: When I first discovered EV I got a patent and there are a lot of people on the edge of violating that patent, but there is at least one radar company I’ve been talking to a little bit about the future of that, and that will happen. It’s only a matter of time because everything that Effective Velocity stands for has been tested thoroughly. It’s taken a long time but analytics has clouded or muddied the water a little bit. It’s really hard to see some of the stuff that is going on, as long as you’re looking at it through that lens.

I can show you a nine-pitch at-bat against a pitcher who throws 94 and he throws a slider, and he’s facing Kris Bryant. He throws him a steady diet of fastballs in and sliders away that have a really good tunnel. He’s dead late on the fastball, he’s ridiculously early on the slider and then he finally after nine pitches – after being early or late on every single pitch – he saws off his bat. And because of the shift, the first baseman’s in and it hits the cut of the grass – a popup – and he ends up with a double. His isolated power goes up, his slugging goes up, every sweetheart number that analytics likes goes up with his at-bat. It’s literally the perfect example between the difference of EV and that.

In the world of analysts who talk about what’s going on in baseball, they haven’t figured out any kind of way to predict things. So they start making comments like it’s random. We look at all these different ways of analyzing things but it’s random. My answer is, what are you looking at? It’s not random, it’s so ridiculously predictable.

We went on national television and predicted how the hard-hit balls were going to go in the World Series and we were within two percentage points in every category. It happened exactly the way we predicted all through the playoffs, not just the World Series. There were 105 homers hit last year and we predicted that 50 percent of them would be exactly like this, they would be within six mph. And as it turns out it was right on the money. The numbers were like 52 percent instead of 50, 22 percent instead of 20. The reason it’s not exact is because every team has a different philosophy of sequencing and when they make their sequencing mistakes they will add to the pot of one of those categories.

At the end of the day they’ll wake up, they don’t have any choice. They’ll go, oh my gosh, back in 2005 I could’ve bought this! We’ll see what happens, I’ve been wrong a lot about having faith in that people will at some point wake up and see it. But it’s going to happen, it’s inevitable because everything has been tested, I tested it all before I even looked at any MLB stuff. Hitter’s reactionary times are very limited. Every hitter has a game plan that he uses at the plate and when you look at them from an EV perspective you know everything that he’s thinking because his timing statistics scream at you what his game plan is. Then it’s a matter of understanding that.

When I look at scouting reports for certain guys it’s laughable. I just think to myself, what in the world? How can you throw Miguel Cabrera in this down and away area with fastballs, when his exit velocity is 110 down there? How does that number get past twenty guys in the front office when all they do is look at numbers? Yet, we’re going to agree that the way to pitch him is fastballs at the bottom of the strike zone. Are you kidding me? It’s only a matter of time before everyone has this “aha” moment and goes wait a second, we’re a little off on the math here.

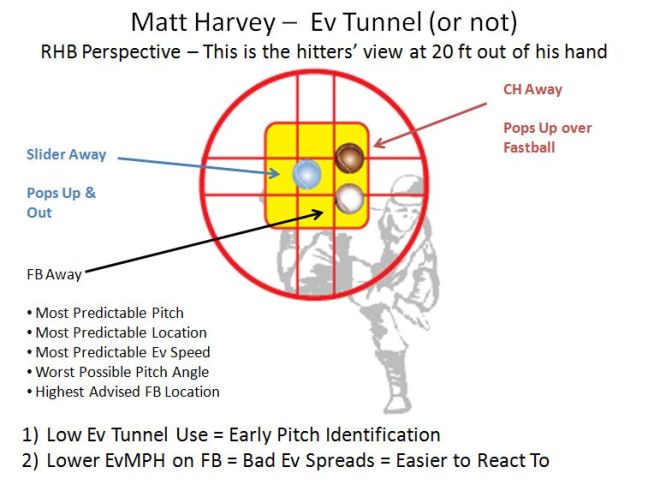

MMO: That reminds me of a blog post you wrote on your website about Matt Harvey earlier this year. You described how his pitch design had a low EV deception rating and also posted low EV speed spreads with his sequence.

Photo from Perry Husband

Husband: If you’ve got a guy that throws 93 with the amount of stuff that he has with a changeup, slider, and curve, he’s a guy that I would go after in a second. When you look at him early on, he was dominant. And he was dominant with a lot of mistakes from an EV perspective, meaning he could get away with some stuff other guys couldn’t. If he really knew what he was doing he’d be lights out, and that’s what you saw on occasion. He was an unhittable guy because he had four pitches that he commanded and when he does it right they all come out of the same tunnel.

But he doesn’t do it right and he doesn’t understand what he’s doing from that perspective. He’s trying to look at historical data about a guy and not the timing of a guy. He’s not looking at what his game plan is, he’s looking at what historical data tells you. He’s trying to pitch to that data and it doesn’t work that way. The real game is happening at real speeds and if you don’t understand the common basic element involved in the game, if that’s not at the core of what you’re doing, you’re flipping a coin every time you go out there.

That’s what’s going on in the big leagues right now is they’re flipping coins. I did a study of all fastballs thrown in the middle of the plate, just because I wanted to have a one-liner about what happens when you throw the ball right down the middle. Guys hit .369 when you throw fastballs right down the middle. In other words, there’s a sixty-one percent fail rate for hitters, even when you throw it right down the middle. That fail rate, in general, it’s probably closer to eight out of ten. There’s probably about an eighty percent chance you’re going to have success as a pitcher no matter what you do. You could literally flip a coin. As long as they’re in reactionary mode you could literally pick and choose how you choose pitches, and today’s big-league pitchers would have success and then not success and then success, success, and then not, not, not.

It’s a flip of the coin as to how many good sequences they have vs. how many bad sequences they have. Even when they have a bad sequence is it going to be one of the ones where a hitter happens to cash in on that twenty or thirty percent rate that they have? Or are you going to get away with that terrible, ridiculous emperor has no clothes sequence? The answer is all of the above. It’s going to happen in all kinds of ways.

One day they’re going to be spot on and dominate, and when I say spot on it’s meaning they’ll have a few more perfect sequences than normal. A lot of cases are they will stumble into something. For example, they can’t get their fastball down and so they spend the whole day throwing fastballs up and thinking, man, I got away with that one. I can’t believe I got away with that one again! And then the only comment he has is yeah, I kept getting fastballs up all day but we’ll fix it next time. [Laughs.]

It’s a happy accident that he couldn’t locate his fastball that day and so he doubled the amount of elevated fastballs and then all of a sudden he’s creating more tunnels by accident. The science that is kind of a faux science that’s running the game right now is missing the most important elements, in my opinion.

MMO: You told me via text that you had some interesting information on Jacob deGrom. Would you mind sharing it with our readers?

Husband: I’m going to do a study on him coming up. When I did a quick glance if you just look at his location of fastballs in general, you’re going to see that if you drew a diagonal line – an EV line – against right-handed hitters and you look at the fastballs in general, where are they? The answer is they’re up above that diagonal, they’re on that plus side of the strike zone. Which automatically sets it up when he throws a slider; it’s going to have a better tunnel and it’s going to have a better EV spread.

What the world has been doing with their fastball is turned it into a medium ball because they’re really throwing it in areas where it’s gone away from its fastest version and now it’s actually losing velocity on the outside part of the plate. All he’s really done is stop blurring his pitch types; he’s started throwing pitches that actually make sense from an EV perspective. That’s the only thing that he’s done differently.

When you look at it from a quick glance it’s ridiculously simple. He’s started to use tunnels, he’s started to use timing against hitters, and he’s taking away their reaction time by hiding pitches better. And he’s adding speed to his fastball instead of losing it, so he’s forcing them to have to respect 100 mph.

When you do that you make the decisions more difficult.

MMO: Thanks for your time, Mr. Husband. It was great speaking to you.

Husband: Thanks very much.

Check out Perry’s website here.

Follow Perry on Twitter, @EVPerryHusband