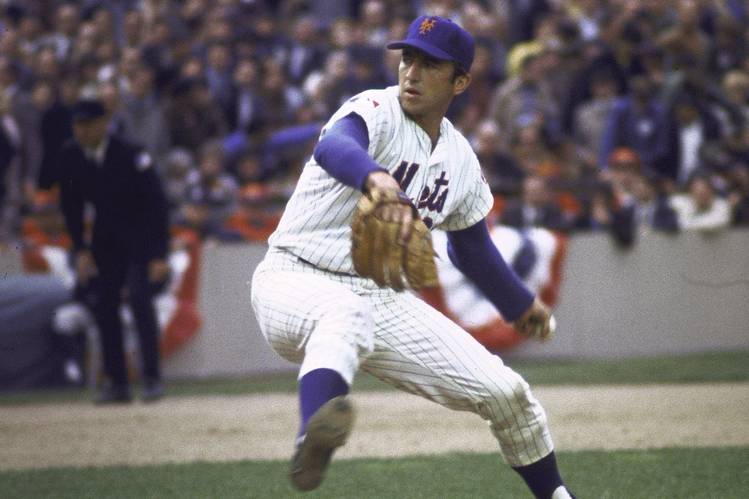

The 1969 World Series saw Jerry Koosman pick up the win in two of the four Mets victories. His ERA was 2.04 and he allowed only 7 hits in 17 2/3 innings pitched.

Ron Swoboda hit .400 and made arguably one of the best catches in Series history. Tommie Agee outdid his teammate and made two unforgettable catches which will live forever in Mets folklore.

However, none of these Mets would win the World Series MVP. That honor went to a man who was not even on the Mets opening day roster. A man who, in March 1969, announced his retirement from Baseball.

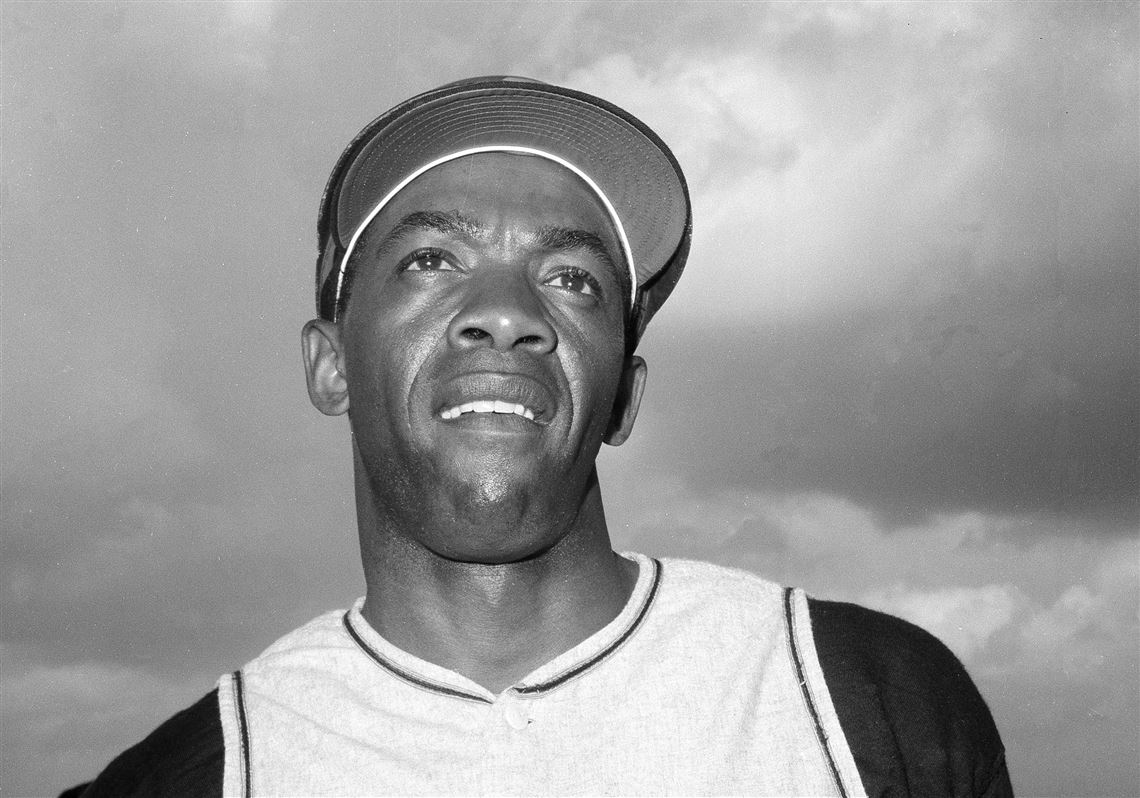

Donn Clendenon was born on July 15, 1935 in Neosho, Montana. He was only two-years-old when his father died of Leukemia and his mother moved the family to Atlanta. Baseball was the farthest thing from his mind.

Clendenon was an intelligent young man who displayed athletic gifts at a very young age. His mother wanted him to be a doctor but Donn wanted to be a lawyer. His step-father, Nish Williams, had played in the Negro Leagues and pushed his son to play baseball.

However, being a black man in the deep south in the 40’s and 50’s, Clendenon realized he would not have an easy go out of it no matter which road he chose. Clendenon recalled, “I knew if I didn’t play baseball, I wouldn’t get my allowance.”

So to placate his father he played ball. They agreed that he would pursue a baseball career as well as getting a degree. This way, if baseball did not work out, he would have something to fall back on.

Growing up it was commonplace for some of his dad’s friends from the Negro Leagues to stop by and talk baseball. It was routine for Donn to chat about the game or have a catch with the likes of Satchell Paige, Jackie Robinson or Roy Campanella.

Clendenon attended Morehouse University in Atlanta. It was a top-notch school geared towards African-American men. Freshmen were assigned ‘Big Brothers’ to help them acclimate to college life. Donn’s ‘big brother’ was Morehouse alumnus, Martin Luther King Jr.

Although he was drafted by the Cleveland Browns of the NFL as well as The Harlem Globetrotters, Clendenon accepted the offer put forth by the Pittsburgh Pirates. He debuted with the Bucs in 1961 but did not become a regular until ’63.

The hulking first baseman, Clendenon put up some solid numbers from 63-66, averaging a .289 batting average with 17 homeruns and 78 RBIs. But he was constantly overshadowed by two teammates who possessed more talent. Their names were Willie Stargell and Roberto Clemente.

In spite of having a fluid, smooth swing, Clendenon led the NL in strikeouts twice. In ’67 and ’68, his numbers dropped off considerably, so Pittsburgh left him unprotected and he was picked up by the expansion Montreal Expos.

Donn was less than thrilled to be going from the powerhouse Pirates to the first-year club, but he was determined to make the best of it. However, the Expos quickly traded him to the hapless Houston Astros.

Not wanting to return to the deep south and face racism, Clendenon, at the age of 33, instead chose to retire. Ultimately, he was talked out of it by Expos brass and commissioner Bowie Kuhn. But he was still unhappy in Montreal.

In June of 1969, Clendenon’s luck would change and he accepted a trade to the New York Mets. It was widely known that the Mets had been a laughing stock since their inception in 1962, but this season, they were starting to open some eyes. On June 15, Donn was sent to Queens in exchange for Steve Renko and Kevin Collins.

“When we got him,” said shortstop Buddy Harrelson years later, “we became a different team. We never had a 3-run homer type of guy. He was always humble, never cocky. We were still young kids. He was the veteran that came in and made us better.”

Harrelson added, “When you threw him into the mix, we became a dangerous force.”

Tommie Agee said of his acquisition, “He was the final piece of the puzzle.” “Until he showed up,” explained Ron Swoboda, “we had no chance of winning anything.”

Clendenon’s first game wearing the blue and orange was on June 17. The Mets lost to the Phillies, 7-3, and fell 7 ½ games back.

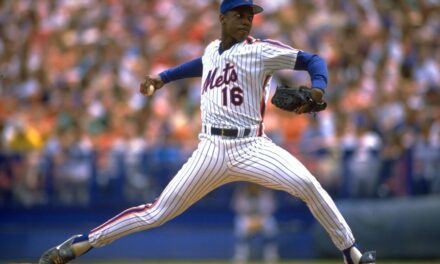

The Mets had the pitching. The Mets had the defense. Now the Mets had the power. He came to be known as “Clink” or “Big Clink.” Standing at 6-4 and 205 pounds, the big first baseman with the big glove and bigger bat would lead the Mets down the stretch, clubbing 12 homers the rest of the way.

On September 24, 1969, when the impossible happened and the Mets clinched the NL East, it was Clink who made it happen. The Mets shelled Steve Carlton for five runs in one-third of inning. Clendenon was 2-for-3 with two homers and four RBIs.

In Game 5 of the Fall Classic, Clendenon was once again at the right place at the right time. The Orioles were trailing 3 games to 1 but the momentum was shifting back their way. Twenty-game winner Dave McNally was dominating the Mets, completely shutting down the offense. The Orioles were leading 3-0 and were threatening to take the series back to Baltimore. In the top of the 5th, Jerry Koosman threw one inside, hitting Frank Robinson who dropped his bat and began walking towards first.

However, home plate umpire Lou DiMuro claimed the ball hit the bat, NOT Robinson. Robinson argued. O’s manager Earl Weaver argued. However, DiMuro stuck by his decision. The replay, in fact, showed that the ump blew the call. It was obvious that Robinson got hit.

In the bottom of the 6th, the Mets were still trailing 3-0 and seemed clueless as to how to figure out McNally. Cleon Jones stepped to the plate and McNally threw one low and inside. The ball hit Cleon’s shoe and conveniently rolled into the Mets dugout. Cleon insisted the ball hit him, but once again, Lou DiMuro insisted it did not.

Mets manager Gil Hodges wasn’t having any of it. He slowly walked from the dugout to home plate. Stoic as always, Hodges held out a baseball with a small smudge of shoe polish on it and displayed it for DiMuro. The ump examined the ball. And then reversed his decision, awarding Cleon first base.

Meanwhile on the other side of the diamond, O’s manager Earl Weaver went ballistic, but after a few minutes order was finally restored and the game resumed.

When order was restored, Donn Clendenon stepped up to the plate and promptly deposited McNally’s offering into the Orioles bullpen. Shea Stadium erupted like it never had before. The Mets would shock the world and go on to win the game and the series.

What a scene as champagne was being sprayed in the clubhouse and jubilant fans were flooding the field. Donn Clendenon was aptly named Series MVP. He hit three home runs, the most ever in a 5-game series, until the record was tied in 2008 by Ryan Howard.

https://youtu.be/XZFVKNluykU

Clendenon returned to the Mets in 1970. He would set a Mets record for most RBI’s in a game (7) and also the most RBIs in a season (97). After the 1971 season, however, the Mets released the aging star. At 36, Clendenon signed with the St. Louis Cardinals, but ended up retiring shortly after.

With his baseball career now at an end, Donn fulfilled his other childhood dream and earned his Doctorate degree from Duquesne University and became a lawyer.

In the mid 1980’s, as he approached 50-years old, Donn became addicted to cocaine. He battled his drug habit for a while and it ultimately cost him his job with the law firm.

In the 90’s, still battling the demons, Clendenon was in a rehab facility in Utah. During a routine physical exam, it was determined that No. 22 had Leukemia. It was the same disease that both his father and grandfather died from. He straightened up, got his act together and conquered his addiction.

Donn moved to Sioux Falls, South Dakota and once again began practicing law. He also became certified as an addiction counselor, helping young adults conquer their own demons.

On September 17, 2005, at age 70, Mr. Clendenon died at his home in South Dakota. In the book, “Miracle in New York,” which was a look back at the ’69 season through Clendenon’s eyes, he talked about his illness. “Every day I wake up now is a blessing. I will eventually die from it. It will eventually take me, I know. But I keep fighting.”