Recently Josh Kosman of the New York Post reported that the Wilpons have refinanced $450 million in SNY debt. Subsequent clarifications in the NY Times and Forbes explained that they refinanced an additional $250 million and still managed to cash out $160 million. They aren’t entirely out of the woods, but there is a growing consensus that they may yet manage to hold onto the team, and they almost have to don’t they?

Recently Josh Kosman of the New York Post reported that the Wilpons have refinanced $450 million in SNY debt. Subsequent clarifications in the NY Times and Forbes explained that they refinanced an additional $250 million and still managed to cash out $160 million. They aren’t entirely out of the woods, but there is a growing consensus that they may yet manage to hold onto the team, and they almost have to don’t they?

The Mets are really all the Wilpons have. No one cares about office buildings or investment securities, but the Mets, well, the Mets have a mascot with a giant head who lacks vocal cords — the Mets get airtime on Letterman and the Daily Show and Family Guy. It is thus perhaps as good a time as any to consider how Fred Wilpon came to own our Mets in the first place and what this ownership group continues to represent for fans who desperately want to believe there is yet hope for our franchise.

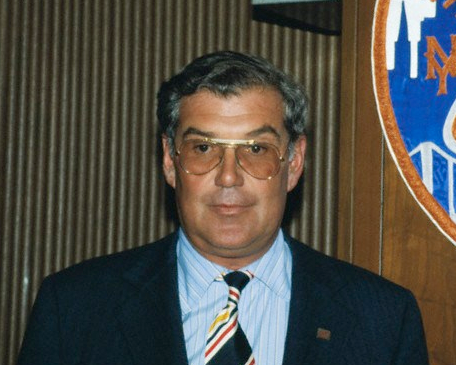

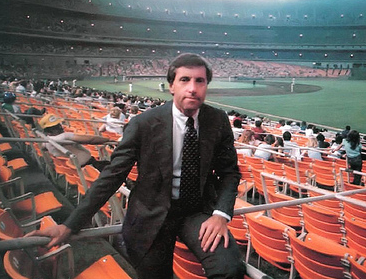

Wilpon and Katz have always appeared vulnerable to the perception that they burst onto the scene as Johnny-come-lately’s (compared to old money blue-bloods like Doubleday), ascending to ownership on the wave of a real-estate boom as a couple of tenement flipping nouveau riche guys from Bensonhurst (no not the fat bus driver and the sewer worker). Wilpon was a West Egger to Doubleday’s East Egg (if I may cite Gatsby), and Katz’ giant brass balls (of note in Toobin’s New Yorker piece) notwithstanding, Doubleday made no qualms about his disdain for Fred.

You see Doubleday never forgave Wilpon for the manner in which he took over half ownership. Nelson Doubleday had even more to say about the way he was low-balled during his buy-out proceedings. N.D. considered the “first refusal” clause that Wilpon used to match Doubleday’s ownership percentage (after the sale of Doubleday & Co.) underhanded because Doubleday never intended that the Mets be part of the deal. The clause was nevertheless present in the fine print as a standard if not forthright real estate maneuver.

Down the road the two sides would end up in some nasty litigation when Doubleday balked at Robert Starkey’s appraisal of the franchise’s value after Doubleday and Wilpon finally agreed to part ways. Doubleday may have had a point as Starkey was a crony of Selig’s dating back to Bud’s Brewer days, but in the end you get the sense that Doubleday had had enough and wanted to be done with his marriage to the Wilpons.

Early in the dissolution negotiations Richard Sandomir of the NY Times reported that Doubleday openly doubted Wilpon’s ability to come up with the kind of money he’d need to buy him out and implied he’d be more than willing to purchase Fred’s share. I believe Doubleday would have bought Wilpon out in a heartbeat if he had the opportunity as he never really intended to share the Mets with Fred.

Doubleday knew you don’t just wake up one day hundreds of millions of dollars richer unless your old Papah leaves it to you in a trust fund, and Wilpon’s father was an undertaker from Brooklyn. These comments by N.D., when looked at through the lens of the Madoff debacle (it is speculated that Wilpon’s involvement with Madoff dates back to around 1986), make one wonder what percentage of Wilpon’s new-found financing power wasn’t perhaps leveraged by artificial means. Of course the case for Doubleday wasn’t helped by the fact that he was a pompous and obscenely wealthy eccentric who occasionally let slide anti-Semitic slurs (detailed in “Lords of the Realm” by John Helyar), but he had a knack for knowing when to splurge on the fans and when to spoil his grandchildren. Doubleday also didn’t endear himself to Commissioner Selig as a long time supporter of Selig’s predecessor, Fay Vincent.

Nelson Doubleday ran further afoul of MLB when quotes were leaked from his lawsuit against Wilpon implying the following against at MLB,“in a desperate attempt to reverse decades of losses to MLB’s Players Association – determined to manufacture phantom operating losses and depress franchise values.”

If Selig wasn’t on Doubleday’s side before those comments you have to believe he didn’t have a lot of warm feelings for him afterwards.

The wording in the lawsuit specifically struck a chord that Donald Fehr and the Players Association were harping on. Selig threatened Doubleday with a million dollar lawsuit and soon afterwards T.J. Quinn of the New York Daily News reported that the quote “was not written by Doubleday or his associates, according to sources.”

Doubleday eventually apologized to MLB and the commissioner’s office for questioning Selig’s integrity and for any controversial comments in light of ongoing collective bargaining negotiations. Doubleday went on to say that his lawyers worded and filed the lawsuit without specifically informing him of the implication that MLB was making attempts at systematically devaluing franchise values by drumming up artificial losses (accusations that in retrospect seem almost prophetic given Selig’s now notorious devices in this regard). Needless to say, Doubleday all but sealed his exit from the owner’s club with these actions and the era of Wilpon began in earnest.

Since that time, Doubleday has come to be seen as the magnanimous and colorful figure who presided over one World Series title and another World Series appearance. Fairly or not, he’s accepted as largely orchestrating the triumph of 1986 by hiring Frank Cashen. From the time of purchase in 1980 when he bought the Mets from the Payson family for 21.1 million, Doubleday was received as a kind of rescuer. Doubleday fulfilled that promise in 1986, and furthered his rapport with the fans by openly pushing for the Piazza deal over Fred’s balmy reservations. He was well-liked by the fans and his absence left an image vacuum in the owner’s box that Wilpon never really seemed comfortable filling. Wilpon, on the other hand, got off to a bad start with the fans by being the thin dour-faced fellow with way too much hair gel who elbowed his way into the partnership that eventually pushed Doubleday out of the picture. Doubleday became a kind of betrayed would-be savior in hindsight, whether that designation was deserved or not (Wilpon was present and involved with both the 1986 and 2000 teams).

Fred’s efforts in filling the ownership vacuum became an exercise in how NOT to conduct a public relations campaign. Doubleday wore bright outfits and had a big personality while Wilpon’s sullen and reserved demeanor and ridiculous paranoia over his own public image led to some awkward missteps both with the press and the fans. Wilpon seemed to become obsessed with cultivating and maintaining a sterling reputation, as he and Katz seemed to be caught in a perpetual P.R. struggle against the perceived notion that there was little separating them from a run-of-the-mill moneybags slum-lord.

Fred’s efforts in filling the ownership vacuum became an exercise in how NOT to conduct a public relations campaign. Doubleday wore bright outfits and had a big personality while Wilpon’s sullen and reserved demeanor and ridiculous paranoia over his own public image led to some awkward missteps both with the press and the fans. Wilpon seemed to become obsessed with cultivating and maintaining a sterling reputation, as he and Katz seemed to be caught in a perpetual P.R. struggle against the perceived notion that there was little separating them from a run-of-the-mill moneybags slum-lord.

You can imagine Fred perhaps even feeling ostracized as a new-money “East Egger” (the Madoff proceedings might have all but cemented that perception for some), but in the end they did still own the Mets, and that was their great redeemer. The Mets are their legacy, their badge of honor, their Plaza Hotel, their claim to elite standing. If the Wilpons had a family coat of arms the Met “NY” would be at its center. Owning the Mets gained admission for them to all sorts of exclusive circles and country clubs that only the likes of Doubleday were formerly privy to. For these reasons (among others) there is not a snowball’s chance in hell the Wilpons are going to give up the Mets unless they absolutely have no choice, unless the team is pried from their cold dead hands (or they end up floating face down in a swimming pool).

Sadly, Fred’s desire to keep the Mets “in the family” speaks to an identity driven disregard for the “public domain” component of a Major League baseball club — the fan base. Fred’s own dream of bringing the Dodgers back and filling the abdicated longings of a failed baseball career and a childhood marred by the loss of his beloved team not only hints at his own self aggrandizement but points to a profound misunderstanding of the true Met ethos. Our unique identity — born from the modernist intonations of the 1964 Worlds Fair — not only stands apart from old NY’s baseball culture, it is in many ways diametrically opposed to it. The Mets are all that is new and different, quirky, inventive, and charming.

The Mets are lovable in losing, and occasionally boisterous and unstoppable. They are Tom Seaver and Cleon Jones and Tug McGraw and Lee Mazzilli and Strawberry and Doc Gooden and many other wildly talented players. Wilpon believed he could superimpose his own perceptions on the franchise rather than allow the fans to drive the team’s culture and heritage. The Dodger inspired edifices and rotundas of Citi Field may seem like passing slights to the team’s true character, but they point to an owner who is hopelessly out of touch. It is difficult to envision how these owners, given their history, could possibly prevail upon whatever faculties are available to them to bring about a Met renaissance. Much like Gatsby, no amount of lavish parties or helicopter rides during spring training will convince anyone that they are legitimate to their ambitions.

Like Pandora, Wilpon has let loose all manner of calamities (Bonilla, Alomar, Glavine, Bay — jeez you’d think with a mortician for a father he’d have found easier ways of getting rid of these stiffs) on our Mets, while making every attempt to shut the door on our last remaining hope; a forced sale. But we should not begrudge Fred Wilpon’s unwavering determination to hold onto our team. He is resolute, Like a dog in a manger, unable himself to apportion sufficient resources to effect success while standing in the way of letting another buyer do so. For Fred the Mets are all he has separating him from all the other filthy rich West Eggers, City Field is the one deed he can hold up to the snooty Doubledays of this world to show that he has something they don’t. No, Fred’s not giving up this team, not any time soon. We’re pretty much stuck with these guys unless the team continues to crap itself for several more seasons or things take another dramatic turn for the worse. Our only real hope is that this Sandy Alderson character, on whose forehead you could diagram the human genome with a sharpie, is all he’s cracked up to be, and it’s a fool’s hope at that.