Like all fathers, my dad gave me a hard time about driving too fast as well as “that crap” I listened to. And like most kids, I never listened. Except today. This particular afternoon I was in no particular hurry to get to my destination, nor was I in any frame of mind to listen to Bruce Springsteen or Van Halen. I preferred to be alone with my thoughts.

It was spring but for the first time in almost forty years of being a Baseball fan I had as much as interest in the Mets as I did in singing along to ‘Jungleland’ or playing air guitar to ‘Unchained.’ It just didn’t matter.

It was spring but for the first time in almost forty years of being a Baseball fan I had as much as interest in the Mets as I did in singing along to ‘Jungleland’ or playing air guitar to ‘Unchained.’ It just didn’t matter.

I parked, and with heavy footsteps I flicked my cigarette into the ashcan and shuffled my feet inside.

The foyer was decorated to resemble a 5-star hotel. The collection of chairs and sofas in the center were occupied with sullen family members whose expressions were laced with both helplessness and hope, despair and desire for a miracle. To my right was an alcove with books. A withered, frail looking woman sat listlessly in a wheel chair, an open book perched unread in her lap, with her head down, an oxygen tank at her side. To my left the ‘front desk.’ This was no 5-star hotel. This was a care center, a convalescent facility or whatever the 21st century euphemism was for a nursing home. Never had I imagined being here.

I made my way to the ‘front desk’ and gave my father’s name. I showed my ID, wondering why the heck someone would be here unless they needed to be. She scribbled the room number on a piece of paper for me. I proceeded through the labyrinth of corridors toward a remote corner of the facility.

The hallways were filled with an antiseptic aroma and metal carts of slop that was evidently dinner. The rhythmic beep-beep-beep of heart monitors and other medical devices wafted gingerly from rooms. I kept my head up, eyes forward. Or tried to. Scanning the room numbers to verify I was heading in the right direction, curiosity got the best of me.

My eyes scanned a room here and there. Some beds were occupied by infirmed forms, small and outwardly defenseless, emaciated souls. Other beds were empty. Somewhere I heard the steady drone of someone flat lining followed by the hurried footsteps of RN’s.

I continued on.

It was March, a time normally my dad and I–and fans everywhere—were filled with optimism about the forthcoming season. Under normal circumstances, we’d banter back and forth about the Mets. My dad would typically be laced with unbridled optimism whereas I figured we’d be lucky to finish 500.

Perhaps this year, however, things would improve. We had a new GM and a new manager. Surely, Jason Bay would bounce back, Carlos Beltran would be healthy, Jose Reyes, in the final year of his contract, would likely put up good numbers and Mike Pelfrey would improve on his 15 wins the previous year.

But at this moment, I didn’t give a damn. I wasn’t thinking of the 2011 Mets.

I also wasn’t thinking of the 1973 Mets.

It was my first season being a fan and after my parents and I relocated from The Bronx to Queens, my time in third grade was off to a bad start. I bolted through the doors at 3pm, ran down the sidewalk darting between classmates, ran into traffic without waiting for the crossing guard and raced home as fast as my little 7 year-old legs would take me. As soon as I arrived, I fell against my mom sobbing.

My classmates—my new classmates—were picking on me, teasing me, ridiculing me for being a Mets fan. It was September 1973 and my team was in fifth place. How embarrassing! My tears eventually stopped and I asked my mom to please not tell dad I cried. After all, I’d be turning 8 soon. Only little kids cried.

Naturally, as soon as my dad got home, she told him. During dinner I denied sobbing, throwing my mom under the proverbial bus. My dad eventually got me to come clean.

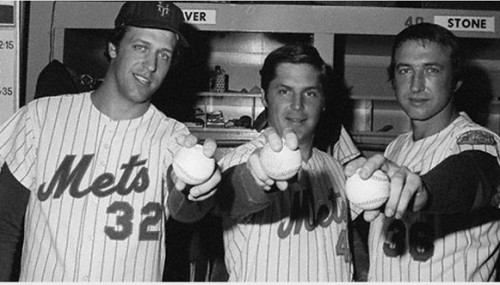

He explained that even though we were fifth, “We have ‘em right where we want ‘em.” He enlightened me. Every day someone in front of us will lose. If we win, we’ll pick up ground. All we had to do was win. And keep winning. “We have Seaver, Kooz, Matlack and Tug in the pen. How many games you think we’ll lose these next three weeks? Not many.” He paused. “And what does Tug say? C’mon, what does Tug say?”

“Ya gotta believe.”

“Right, ya gotta believe,” dad repeated. “Nothing to worry about. Now, go finish your homework.”

I walked away from the kitchen feeling confident.

Out of the room now, my mom asked my dad, “You really think they’ll win?”

My dad lit up a cigarette, sipped his coffee and shook his head. “Nah, no way. They’ve got no chance. They’re too far back.”

“What’re you going to tell Rob when they lose?”

My dad shrugged. “I’ll worry it about then. But at least he feels better now.”

The Mets of course won the pennant and came within one swing of winning the World Series. And somehow, as a little kid, I wondered if my dad truly had something to do with that. After all, he said we’d win the NLE. And we did.

But this was 201l as I continued through the hallway amidst the steady din of moans and wails of declining souls.

I wasn’t thinking of 1974 when my dad secured us two seats in the press box two booths down from Lindsey Nelson, Bob Murphy and Ralph Kiner. I wasn’t thinking of 1975 when we went to a game we weren’t supposed to, sat in a section we never did and my dad caught a foul ball, the only one he ever would in a lifetime of going to both Shea and Ebbets Field. I wasn’t thinking of 1976 when my dad consoled me, explaining that Baseball was not a game but a business and tried to get me to understand why my team would trade away my favorite player.

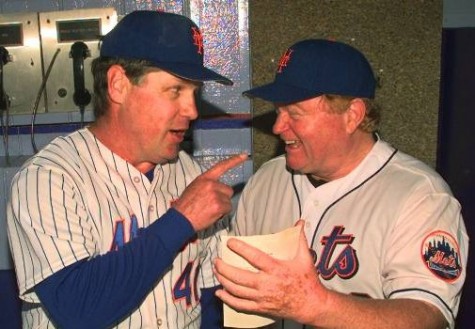

It wasn’t June 15, 1977 when this 11 year-old ran out of his bedroom and told my dad I just heard on TV we traded Tom Seaver. Nor was it exactly six years later when this 17 year old drove home, two days shy of graduating high school, walked in and saw my dad beaming from ear-to-ear. “We signed Keith Hernandez!”

I wasn’t thinking of 1986. Jesse Orosco fell to his knees and my dad and I jumped to our feet, hugging and dancing around the living room like little kids. At that moment, we weren’t father and son. There wasn’t 23 years between us. And since I was too young to remember 1969, this would be the only Mets championship we got to share.

I wasn’t thinking of 1988, a day when my new wife invited her new in-laws over for dinner and my dad had to weigh between a good father-in-law or watching game 4 of the NLCS. After Mike Scioscia hit that damn HR neither my dad nor I had much of an appetite.

I wasn’t thinking of 1998 when my parents were vacationing in Hawaii and forgetting—or perhaps not caring about the time difference—picked up my cordless phone, woke my dad in the early morning to advise him we signed Mike Piazza. I wasn’t thinking of 2005 when he called me on my cell to advise me we signed Pedro Martinez.

No. This was 2011. I approached my dad’s room, all the memories—a lifetimes’ worth in what now felt like the blink of an eye—didn’t matter. I was about to enter a dreary chamber in the far corner of a nursing home where a lifetime of smoking had caught up with him. I didn’t give a damn about Seaver or Hernandez or Orosco or Piazza or any of them. I just wanted my dad better. And out of this place.

I took a deep breath, steeled myself as best I could, and crossed the threshold.

“Hey, dad!” I said with enthusiasm I didn’t feel.

He drew his eyes back from the partially closed verticals and the setting sun. He looked gaunt, tired, and defeated. He readjusted his thin gown but not before I realized how skeletal his collar bone appeared. “Hey, Rob.”

Pulling a chair over I asked, “How ya feeling?” Stupid question.

He shrugged. And then asked me something that threw me for a loop. “Did we sign anyone today?”

I was appalled, stunned, shocked. “Huh?”

“Alderson make any moves?”

I may have rolled my eyes. I may have smirked. I truly don’t recall. What I do recall was utter astonishment. My dad should’ve been fighting. He should’ve been thinking about chemo, radiation and beating this damn thing. Instead he was thinking about the Mets??? “I have no idea, dad.”

I stayed as long as I could, kissed him on the head and eventually went home. As I retraced my earlier steps, I couldn’t shake it. Why the hell—how the hell—could he be thinking about Baseball at a time like this? The end was coming and he was asking about the stupid Mets?

It didn’t hit me until weeks after I lost him.

He knew what was pending, knew it was inevitable. But yet, he was hoping, longing, yearning for just one more summer, one more chance. He was craving a sense of normalcy in his life. Like every spring starting in 1949 he was asking for one more season, one more summer, 162 more games with hopefully a few more tacked on in October.

I still have the same sofa I did in 2006 where we sat side-by-side watching the last post-season game the Mets played. When Endy Chavez made that catch my hands clasped my head like Ray Knight rounding third. I looked right. My dad was stoic until saying, “He caught that?!”

“Oh my God! Oh My God! Yes! That’s better than Agee’s or Swoboda,” I shouted in disbelief.

My dad arched an eyebrow. “Calm down.” The ’69 club always held a special place in his heart. “David Wright?” he said numerous times. “Nice kid, but he’s not The Glider.”

An hour later I managed to pull my eyes away from the TV as Carlos Beltran took that called strike. My dad kept looking straight ahead, trying to cope with 2006 ending the way it did.

In less than a week the Mets will return to the post-season. This time, however, there’s an empty space on the sofa. I won’t be looking right this October. Instead I’ll be looking up, a bittersweet smile, thinking, “Dad, you missed a hell of a year.”