I looked up at my parents. My mom gripped my dad’s arm, patting his back lovingly. My dad stood, gazing down, dabbing his eyes. My family made the somber journey to the cemetery on Long Island a few times during the year, usually around the Jewish holidays and always on Father’s Day.

I followed my father’s sight-line, reading the inscription on the marble gravestones. I had no memory of my grandfather who died when I was just three, and only a fleeting remembrance of my aunt, my dad’s sister, who died a year later. I studied the dates. My grandfather lived until he was 67. Really old. My aunt succumbed to cancer at age 39. To a boy of 7, 8, and 9, even 39 seemed old.

My mom would sob. My dad would weep. I wanted to be an adult, a grown-up. I tried to cry. I even tried to fake it once or twice. But the tears wouldn’t come. To me, these people we were paying our respects to were little more than names and dates. And with the innocence, self-centeredness or perhaps naiveté of a young boy, I didn’t make the connection. I was unable to wrap my child’s mind around the concept that the man resting in peace was to my dad the same as my dad was to me.

Unable to locate the grief my dad felt, I sauntered off to find three stones—two larger ones for my parents, a pebble for me—to place atop the headstone. At least I could feel like I was doing something beneficial. I couldn’t cry so at least I could scour the grounds for rocks.

There are those times in one’s life when we remember precisely where we were and exactly what we were doing. On a Tuesday morning in 2001, my wife crawled out of bed to answer the ringing phone. She returned a moment later, telling me her mom called and advised her a plane flew into one of the Twin Towers.

On April 19, 1995, I was at work when a colleague of mine began freaking out. She was from Oklahoma City and apparently a bomb had destroyed a building, killing and injuring hundreds in her hometown.

On Monday night, December 8, 1980, my mom was reading in bed. My dad and I were watching the local news waiting for the sports, hoping the Mets did something. After the break, Roland Smith appeared on the screen and informed his viewers of the big breaking news: Former Beatle John Lennon had been shot on the upper west side.

I thought nothing of it, told myself it was just a grazing. Surely, someone of John Lennon’s ilk couldn’t die. That only happened to us common folk…or to people who died that I had no memory of.

Just a few months later I picked up the ringing telephone, back when they were still called telephones, not landlines. My grandmother was stammering, asking to speak with my mom. Something about President Reagan getting shot. It was the only time I ever heard my grandma cry.

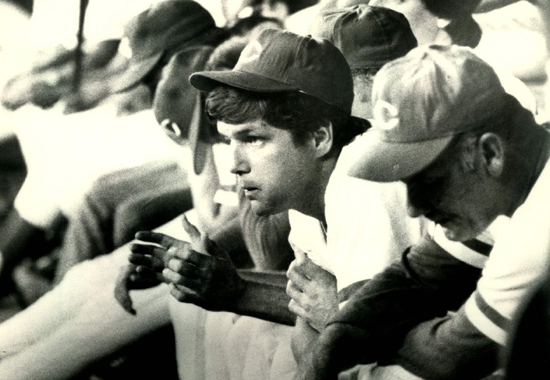

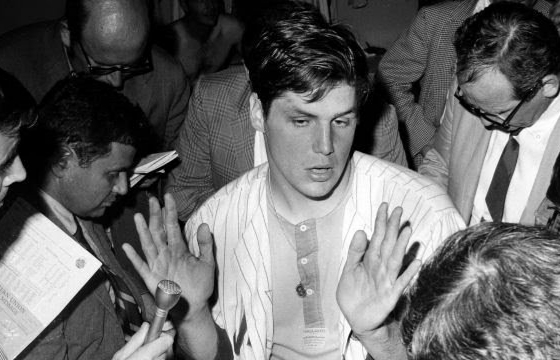

Wednesday, June 15, 1977 is a day when all Mets fans remember exactly what they were doing.

It was almost 9:00 pm. My dad was watching Baa Baa Black Sheep, a show about a USMC aviator during WWII starring the very hot at the time, Robert Conrad. I meandered off to my bedroom and turned on the little 13 inch b&w RCA my uncle had given me. I adjusted the rabbit ears and prepared to watch Charlie’s Angels. I was a few months shy of turning 12 and was starting to realize that maybe girls weren’t so icky after all.

I’m not sure who it was or the exact words the sportscaster said. But the message was irrefutable. I raced from my room and shouted, “Dad, dad, we just traded Seaver!”

My dad arched an eyebrow at me, then glimpsed at my mom. I was a practical joker, a smart-ass even back then. But even I wouldn’t stoop to that level and speak such sacrilege. “They didn’t trade Seaver,” my dad smirked. “Wouldja stop.”

“That’s what they said.” I deflected blame, pointing down the hallway as if my dad had forgotten where my bedroom was located.

He stared at me, did a double-take at my mom. “Oh, please, they wouldn’t trade…” He didn’t finish the sentence. He couldn’t. His mind quickly flashed back on the recent turmoil between The Franchise and team executives. He looked at me again and asked haltingly, “Seaver?”

I pointed down the hallway a second time. “Yep.”

Always a die-hard Mets fan, always looking for a bright spot, and always hoping for a better tomorrow, he asked half-heartedly, “Who’d we get?”

I shrugged.

Attempting to come to terms with the unthinkable, with trying to imagine a rotation without Seaver, the man who guided the Mets to two pennants, one World Series, countless fond memories, and would probably be enshrined in the Hall of Fame one day, the man who would now look silly wearing a Reds jersey, the man who was the face of the 15 year-old organization, my dad exchanged glances between my mom and I.

Realizing I was not simply messing with my old man, my dad let loose. He stormed across the living room, angrily turned off the meaningless TV show and grabbed his Marlboro’s. I had to cover my ears during portions of those George Carlin specials on HBO, had to cover my eyes if a sex scene came on during some movie and never heard my dad use the F-word. Until June 15, 1977.

To this prepubescent boy, I recognized some things were as important in life as Baseball. I left my dad behind to wonder what the Seaver-less Mets would look like and returned to my room to look at Jaclyn Smith.

It was during the first commercial break when I remembered the rest of the story. I ran out of my room. “Hey, dad,” I began. “They traded Kingman, too.” I paused, paralyzed by fear. A feeling came over me I’d never felt before. A feeling I didn’t like.

My mom had her arm draped over my dad’s shoulders, her trembling hand tightly clutching his. There was a quiver in her words. “Are you having chest pains? Any shooting pain in your arm? Can you breathe?”

My dad was chain smoking cigarettes. The ash tray before him more full than it had been twenty minutes ago. His right hand held a cigarette, his left hand pressed over his heart.

With the speed of a Tom Seaver fastball, the F-word flew from my dad’s mouth, using it in conjunction with M. Donald Grant and Dick Young.

“If Joan Payson was still alive, this wouldn’t have happened,” he said with that familiar sadness in his voice.

My mom repeated her questions.

In tunnel vision, I watched the terrifying scene playing out before me. My lips became parched. My throat desert dry. I couldn’t speak and felt my wobbly legs carry me over to the sofa. I was 11 years old. My dad was almost 35. Pretty old…

I looked at my dad. But I thought of my grandfather on Long Island. I made the connection.

The pain in his chest passed. The pain of losing Tom Seaver not so much. How could they do this to us, I thought. Seaver was like family…

Four days later, June 19, was Father’s Day. We made our customary pilgrimage to the cemetery. I looked up at my parents. My mom gripped my dad’s arm, patting his back lovingly. My dad stood, gazing down, dabbing at his eyes. I looked at my dad—a little longer than usual.

My eyes found their way to the name on the headstone. I swallowed down the rising lump in my throat. This time I didn’t need to fake the tears… I knew what loss felt like.