Why I Started Looking At Deferred Contracts

The running joke by many baseball writers, fans, and TV networks was the deferred contract the Mets agreed to give Bobby Bonilla. Instead of simply laugh, I decided to dig deeper into his contract and deferred contracts in-general.

I realized that the deferment with Bonilla actually worked out for the Mets in some regards – allowed them to acquire Mike Hampton which ultimately led to the compensation pick of David Wright – and that deferred contracts were happening way before Bobby.

While looking at all of the deferred deals, I realized that some of them actually made sense for both the player and the team. It allowed the team more payroll flexibility (and luxury tax which Chris covers later) to sign other players and if there’s no interest involved, actually saved them money. From the player perspective, it assures them they will be getting paid after their playing days are over and even better for guys like Manny Ramirez that will receive interest.

Overall, I believe it’s important to look at each of the deals and see what they meant for the team at the time. What did it allow them to do? Did they benefit from being able to do it? (Looking at the 2019 Washington Nationals, franchise with the most current deferred contracts out there and future)

Then look at how it could affect the team in the future. Again, the Nationals are a key one to look at when they start paying Max Scherzer $15 million a year from 2022-2028 in deferred payments and will also be paying deferred money to Stephen Strasburg, Patrick Corbin, and Rafael Soriano during that time.

When you go through the list of deferred deals I tweeted out, you see there’s a ton of stars – Ichiro, Ken Griffey Jr. Manny, and Todd Helton – but there’s also lesser known players like Brian Dozier, Matt Wieters, and Wei-Yin Chen.

You will also see that the three teams the most active in giving deferred contracts in recent years are the Orioles, Nationals, and Mets. One last note is that not all deferred payments are made on July 1, some contracts stipulate other dates like the $3 million payment Daniel Murphy received form the Nats on January 15 of this year.

A Brief History of Deferred Contracts in Baseball, by Jacob Resnick

Though deferred money has been a part of baseball since the early 20th century, typically in the form of retirement benefits — Sparky Lyle signed a contract with the Texas Rangers in which he also agreed to broadcast their games for 10 years after he stopped playing — the influx of modern deferrals began once free agency had moved past its infancy and the game’s stars started signing long-term contracts on the open market in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

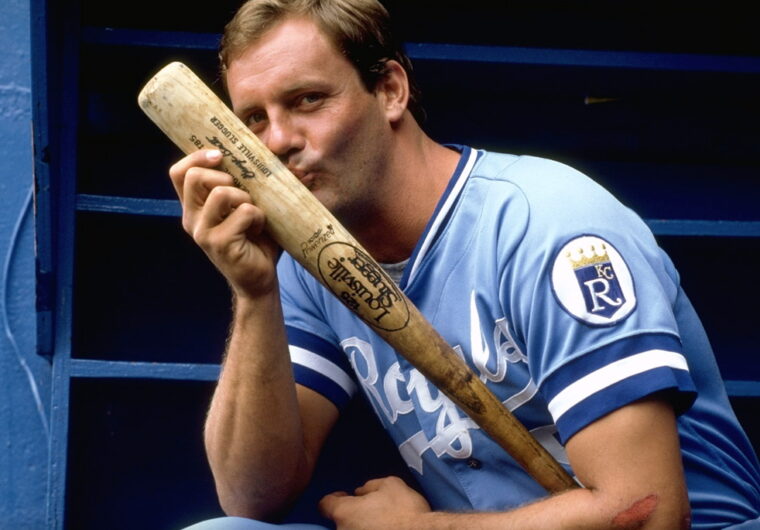

The most well-known of these early deferred contracts is Bruce Sutter‘s six-year deal from the winter of 1984 that called for 30 years of additional payments through 2021.

But other big names, like George Brett, Bert Blyleven, Rich Gossage, Tommy John, Phil Niekro, and Dave Parker, hopped on the trend early, too.

In fact, Niekro, despite signing a three-year deal with the Atlanta Braves that ended in 1982, received $8,500 per month through 2010, when he turned 71 years old.

Gossage signed with the San Diego Padres in 1984 and guaranteed himself six-figure yearly payments through 2016. It’s hard to imagine that General Manager Jack McKeon (or anyone alive, for that matter) had any concept of the year 2016, 32 years earlier.

The first time a team had an uh-oh moment after agreeing to lengthy deferrals came in 1986, three years after former MVP Dave Parker played his last game with the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Originally scheduled to receive yearly payments from 1989 to 2007, Parker was sued by the Pirates for “breach of contract on the ground that his use of cocaine had defrauded the team.”

The lawsuit was settled in 1988. The terms were not disclosed, but Pittsburgh ended up paying significantly less than the nearly $1.5 million due in deferrals — and in one lump sum payment, too.

As the 80s turned into the 90s and the 90s turned into the 21st century, contracts began to skyrocket.

When it came to players like Alex Rodriguez, who signed a massive ten-year deal in excess of $250 million in 2001, the only way to mitigate the complications of employing a player that makes insanely more than his teammates is to defer significant portions of the contract over twenty years down the line.

From a team and owner perspective, it all makes sense. Perhaps the ownership group signing the contract won’t even have control of the organization when those final few payments are made.

For win-now clubs, the ability to fit an extra player or two into your payroll by deferring portions of other players’ salaries can be a weapon.

The Baltimore Orioles tried to extend their window by handing out a combined $258 million to Chris Davis, Yovani Gallardo, Darren O’Day, and Mark Trumbo over the 2016 and 2017 offseasons. It obviously didn’t work out for the team, but it didn’t kill Peter Angelos’ pockets, either, as $54 million of the total was deferred. (It does mean the Orioles will be paying Davis over $1 million when he’s 51. Sheesh.)

Baseball owners have always operated with a money-saving mindset. The only difference is now they’re on the hook for multi-hundred million dollar salaries, as opposed to the five-year, $7.5 million contract that Parker signed in 1979 that made him the highest-paid player in the game.

With no sign of salaries slowing down, it’s only right to assume that deferral checks will continue getting larger as well.

Understanding the Economics of Deferred Contracts, by Christopher Soto

A dollar today is worth more than a dollar tomorrow.

This statement is starting point of any conversation when discussing any form of deferred compensation. It wasn’t that long ago when even a $15 million per year contract was considered record setting. In December of 1998, the Los Angeles Dodgers signed a Cy Young candidate in RHP Kevin Brown to a record setting seven-year, $105 million, contract the largest in baseball history in terms of total dollars and average annual salary. This bested Mike Piazza‘s $91 million deal as the biggest in total dollars and Mo Vaughn‘s $13.33 million a year deal as the highest average annual salary. Yet nowadays, $15 million is what you expect to pay for a back-end of the rotation starting pitcher while Cy Young candidates are regularly topping $30 million per season.

This, my friends, is inflation. As time moves on things become more and more expensive. Its not just a concept in sports. We as individuals experience it everyday in your own lives. The Swiss Cake rolls from the corner store that I use to buy after school for a quarter, I now have to pay a dollar for if I want to grab them after work. The same dollar bill that could buy me four of them back then, can only buy me one now. Seems like a pretty raw deal, right?

Now think of these in terms of your salary. You work a nine to five job for $100,000 a year, but your employer only pays you half of your money now with the other half ten years from now. You find yourself comfortably able to live on $50,000 a year with no problems and when you retire in ten years you look forward to the $50,000 a year you will receive every year. However, ten years from now, your not able to live as comfortably anymore. Food is more expensive, Rent is higher, insurance, transportation, medical bills, everything is more expensive now making that $50,000 less valuable.

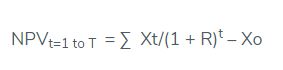

That is the “time value of money” and why more and more teams are choosing to structure the largest contracts in the game to include deferred compensation. In today’s current MLB collective bargaining agreement, deferring compensation is also a way teams can get around the normal rules of staying under the established luxury tax line. Since, for MLB Luxury Tax purposes, player contracts are accounted for based on the Average Annual Value (AAV) the calculations for it are generally just a very simple mathematical $/years calculation. However, how does one account for money that players are earning in a year, but not receiving until 10,15,20 years from now? That’s where the term “Net Present Value” comes into play.

Said more simply, we need to figure how much the compensation we are deferring is going to be worth in the future when we actually pay it out. Does anyone have a crystal ball to tell me what inflation is going to be in 2030? Thankfully, we don’t need one. Instead we can use something called a “discount rate”. Think of it as the cost of a missed opportunity. What if you had gotten that $50,000 of salary that was deferred and invested it instead? What kind of interest rate would you get on it? By using this, we can figure out how much money your missing out on by choosing to receive your money years later. The difference between what you could have made and what you will make is the discount rate that reduces the Net Present Value of your deferred compensation.

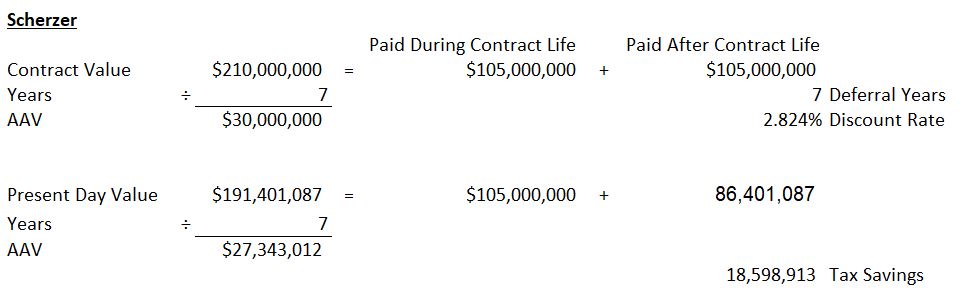

Let’s use Max Scherzer’s contract as an example. In January 2015, the Nationals agreed to sign him to a 7 year/$210 million contract. As part of the agreement though, Scherzer deferred all of his normal compensation from 2019 to 2021 to be paid across seven years after his contract expires (Though he still receives $15 million each year as part of his original signing bonus.) By doing so, this reduces the NPV of the contract by ~$18.6 million helping the Nationals reduce their luxury tax hit by $2.65 million per season. This may not seem like a lot, but the Nationals are an organization that utilizes deferred compensation quite frequently. Scherzer, Ryan Zimmerman, Stephen Strasburg, Daniel Murphy, Patrick Corbin, and several others have all agreed to some sort of deferred compensation deal allowing to Nationals to fit in more high value contracts without exceeding the tax line.

The Mets are no stranger to this concept either (insert Bobby Bonilla joke here), though, presently they don’t use it nearly to the extent that the Nationals do. Most recently, Jacob deGrom‘s 5 year/$137.5 million extension included a maximum of $52.5 million of deferred compensation if both sides don’t exercise opt-outs. The deferred compensation won’t be paid to deGrom until 15 years! after he rightfully earns it. This length and size of deferrals results in a much larger discount rate than Scherzer’s was giving the Mets more luxury savings per year than the Nationals received. Though the flip side of that is the fact that the Mets will be cutting checks for deGrom until he’s 47 through 51 years old.

Both of these contracts are simple examples of how deferred contracts work with no deferred interest built into them. Some deferred compensation agreements in the past have had interest built into them such as the Mets Bobby Bonilla deal or, more painfully, Bruce Sutter’s 1984 six-year contract $9.1 million deal with the Atlanta Braves that deferred the entire amount at 12.3% interest resulting in 30 years worth of $1.12 million interest payments + the final payment of the original $9.1 million resulting in a total deferred earnings of $42.7 million.