Editor’s Note: MMO contributor Stephen Hanks was nice enough to allow me to share this truly amazing article from June of 1984, when he was the owner and editor in chief of New York Sports magazine. It was written by Ross Wetzsteon who does a fascinating job of presenting Rusty unplugged. I loved this piece when I first read it, and I know you will too. – Joe D.

Rusty Staub: The Mets’ Hittin’ Magician

New York Sports, June 1984

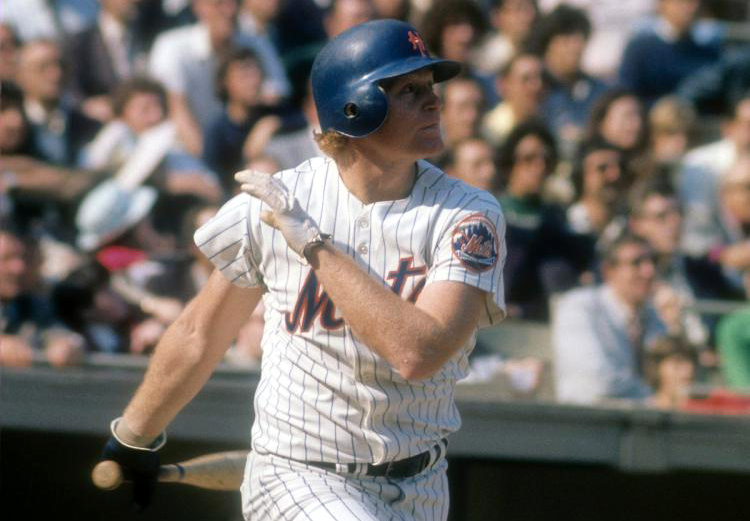

Spring Training, 1982: It’s only an exhibition game, but it’s one of the toughest at-bats in Rusty Staub‘s career. Mark Fidrych is pitching for the Red Sox, and Rusty Staub is as fond of the Bird as anyone in baseball. “There are great guys on every team,” he says, “but there’s always someone who doesn’t like them. The only exception I ever knew was Mark. Everybody loved the Bird. He was the greatest thing that happened to baseball in my 22 years.”

But this is the injury-plagued Fidrych’s last shot at returning to the majors; one more bad outing and his career is over. “I knew what he was feeling,” Staub says, “and I was pulling for him harder than anybody.” Then a shrug. “But he wasn’t wearing my uniform, so I went up there trying to hit a rope. That’s my job.” And as he stood on first base, after hitting that rope, it was the first time in his life he’d ever felt bad about getting a hit. “Well, I never feel bad about getting a hit,” Staub corrects himself with a laugh, “but it was the only time I ever felt mixed emotions.”

Mid-Season, 1983: Shrewdly pin-pointing the Mets’ biggest hole, General Manager Frank Cashen trades for a catch … er, first baseman (Keith Hernandez), putting two guys out of a job. Now Rusty Staub has been saying for a couple of years he’s a better first baseman than Dave Kingman and he’s been saying it to Kingman, too. (“I’m not ashamed to tell people what I believe.”) But Kingman, unlike Fidyrich, is wearing Rusty Staub’s uniform. Rusty knows how Kingman feels about being shunted to the bench. So even though Kingman becomes even more inaccessible to the press, even more aloof from his teammates, Rusty goes out of his way to get closer to him.

“David is a complex person and that makes it tough to be his friend,” he says. “But we had lunch several times, and I talked to him more on the bench. I’d been living with the same problems myself, the least I could do was offer him advice on how to survive mentally.”

“I told him the things that’d helped me most: to always keep in mind that your team-mates come first; to work even harder to stay in shape so you’re ready when they need you; to not get so down on yourself you can’t come through; to ask the good Lord for strength. David and I had never really been close before his time of duress.”

Rusty Staub has as many friends as any player in baseball, but with a game on the line, even in spring training, he’s the consummate, ice-veined competitor. He’s one of the most cooperative interviews in the clubhouse, but cross him once and he’ll never forget it. (A Daily News writer misquoted him in 1975 and still angrily remembering it today, he says, “If that guy’d ever come back to the clubhouse, there would have been an altercation.”) And he’s stubborn about what he believes, sometimes even truculent, but if things aren’t going your way, and you’re wearing his uniform, he’s the first guy there to help you out.

Probably the biggest paradox about Rusty Staub is that although he’s been one of the most popular players wherever he’s gone, he’s also been one of the game’s most unknown personalities. When he starred for the Expos from 1969 to 1971, “Le Grand Orange” was even more beloved than Canadian hockey great Jean Beliveau, but as a Montreal sportswriter recalls, “you could only get to know Rusty up to a point. Beyond that no one had a clue what he was really like.”

And winding down his career with the Mets, he’s become the most idolized pinch-hitter in baseball history [last June tying major-league records for successive pinch hits (8) and total pinch-hit RBIs in a season (25)], and probably the most respected player in the Met clubhouse, yet none of the writers on the Mets beat, or any of his teammates, can say they really know him.

“He’ll answer anything you ask him about baseball,” says one writer—”well, not anything, I’ve seen guys ask him a stupid question, and he either won’t answer or says straight out ‘that’s a stupid question’—but as far as his life outside baseball goes, he’s a complete mystery.” Says a teammate: “We all look up to Rusty, but he’s more of a leader by example than a buddy. I mean he doesn’t hang out with the guys much, not even on the road. Everybody likes Rusty, he’s a class guy, but no one knows him very well. You get back to the clubhouse after a game and he’s gone.”

This is no Steve Carlton or George Hendrick, third fingering the world. This is no Dave Kingman, more temperamentally suited for lighthouse duty in Nova Scotia. This is a likable, outgoing guy, a born restauranteur. Part of the problem is that Rusty Staub has been a kind of elder statesman since he reached the majors at age 19, one of those people who, by virtue of their innate professionalism, always seem much more mature than their peers.

“You’ve got to remember,” says a former teammate from Staub’s early years (1963-1968) on the Houston Astros, “Rusty came up heralded by Ted Williams himself as the best natural hitter he’d ever seen. He was still in his teens, but no one thought of him as a kid. Hell, he seemed like an old pro half way through his rookie year. It created a kind of distance.”

Part of the problem is that Rusty Staub uses phrases like “mixed emotions” and “time of duress” as naturally as other ballplayers use phrases like “he can pick it” or “he took me downtown,” and he can actually say things like “I feel I owe an obligation to the youth of this great country of ours” without sounding like he’s running for office against Steve Garvey.

Part of the problem is that, as one sportswriter relates, “he draws a firm line, no questions about anything but baseball, and anyone who tries to cross it gets a ton of silence.” And part of the problem is simply that he hasn’t settled down in one place. Even playing for the Mets and owning an Upper East Side restaurant that bears his name, he spends over half his time in Houston, Washington and New Orleans.

Whatever the reason, when Rusty Staub takes off his chef’s hat and replaces it with his Mets cap in that familiar American Express commercial and asks, “Do you know me?” most people would answer “no.”

Rusty Staub thought he still had a shot at the sacred 3,000-hit mark when he was signed as a free agent by the Mets in December ’80, only 453 short. But the Mets made another deal for a first baseman later that winter, picking up Dave Kingman from the Cubs.

“That was the most difficult time of my career,” Rusty Staub says, “feeling deep down in my heart that I was the best player at my position and not being given the opportunity to play. When I agreed to come here, I told Frank Cashen I could still play regularly for a lot of teams—the money was going to be the same wherever I went—and I thought we saw eye to eye. But then they made the decision not to use me as a regular. It was the toughest adjustment I’ve ever made in my life.”

Rusty Staub has a way of stopping abruptly when he’s said what he has to say. There’s no hint of hostility, or defensiveness, or caution, just the sense that you’re talking to someone with a professional’s knowledge of the ground rules. You’re asking the questions, I’m answering them, this isn’t a conversation, he seems to be saying. He is open, friendly and straightforward, but always with that firm line.

Staub’s studio apartment is just around the corner from his 73rd Street and Third Avenue restaurant. Inside there is a semi-circular bar with four bar stools, a U-shaped sitting area with green couches, a slightly raised sleeping platform to one side, western paintings on the walls, and a couple of trophies on the shelves. It’s the kind of place a well-off bachelor would use as a crash pad, the kind of place the maid who comes in once a week knows better than the occupant.

Next question. So how did you make that adjustment?

Rusty Staub shrugs his shoulders, extends both arms across the top of the couch. “I talked with myself,” he says. “I asked myself, ‘What’s the most important thing in my life? Should get-ting 3,000 hits be my predominant goal?’ I probably could have made it in the American League but it won’t happen now.”

“Or should being part of the Mets, part of the community, be more important? I needed an outside view, an analytic rather than an emotional view, so I talked to my closest friends about it. I finally decided that the best thing for my life would be to stay here.”

Again that abrupt stop. The professional owes his public an answer, and he’s given the answer. But this time Rusty Staub seems to feel he owes something else. “Another thing,” he goes on, “few people know about this, but Frank Cashen and I had a good meeting in 1982 about my playing situation, and he gave me permission to make a deal for myself, to talk to clubs in the American League about being a DH. I called Ralph Houk, whom I’d played for in Detroit.

But he was the only one I talked to because I started thinking, ‘How many people would do what Frank did for me? If he’d allow me to do this, maybe I’m not judging him right. So that’s why I decided to stay with the Mets. Sure I wanted 3,000 hits, sure I have moments of aggravation about not playing more, but I’m telling you from the bottom of my heart that personal loyalty is more important in my life than those things.”

Next question.

Rusty Staub is no pious phony. You don’t doubt his sincerity for a moment. He’s as straight as . . . well, he’s as straight as a priest. And maybe that’s a clue to discovering what he’s all about, for Rusty Staub is a committed Catholic (he’s not embarrassed to admit that he was once an altar boy and isn’t afraid of seeming corny when he says that his family was “wealthy in love”). He sometimes seems, like many priests, to have so completely immersed himself in his religious values that they’ve become almost inseparable from his personality.

There may be inner conflicts, or “moments of aggravation,” but that’s not who you really are, who you really are is your convictions. (One of the reasons the Astros traded him to Montreal, in fact, was his refusal to play on the national day of mourning after Bobby Kennedy’s assassination—a stand that didn’t go down well in Texas in 1968. “When the President of the United States says there’s a day of mourning,” he still firmly insists, “that means what it says.”) So, like a priest, the distinction between public presence and an inviolable private personality becomes meaningless—and even though you’re a beloved figure, constantly in the public eye, no one feels they really know you.

Everybody knows what Rusty Staub is like as a hitter, though. A reporter once asked Lefty O’Doul how he thought the old-timers would do in modern day baseball. For instance, did O’Doul think Ty Cobb could hit .367 with the advent of night games, the slider, relief pitchers? “Nah,” O’Doul said, “these days Ty’d probably hit .310, .320, something like that.” “So there’s that big a difference?” the reporter asked. “Well, you’ve got to remember,” O’Doul answered, “Ty’s 75 years old now.”

Rusty Staub’s that kind of hitter, a guy who is still nudging .300 at 40 and could probably slap the outside pitch to left while collecting Social Security. In addition to that sweet left-handed swing even Ted Williams envied, he’s a thinking man’s hitter. Not a guess hitter, that’s not what thinking means. Einstein didn’t guess E=mc2, he had a pretty good idea he was right.

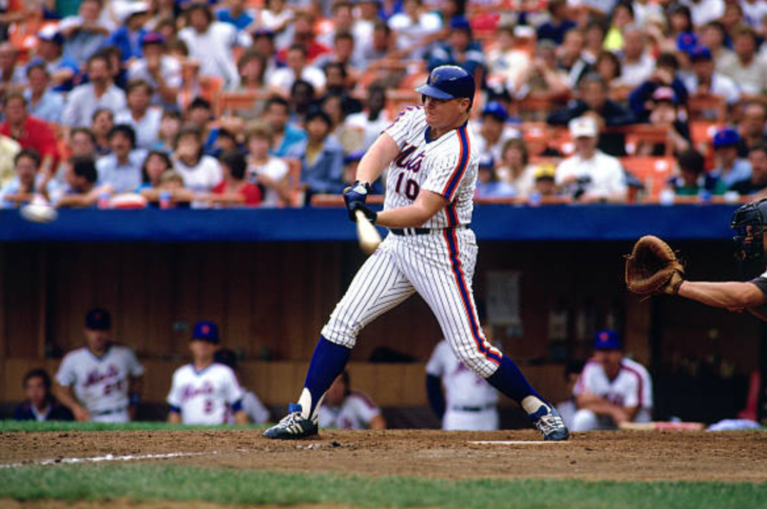

A situation hitter, that’s the way Rusty Staub prefers to think of himself, especially since he’s been coming off the bench. Staub thinks score, inning, outs, count, men on base, park, defensive alignment, pitcher. He thinks about his own strengths and limitations (“the most important part of hitting”), how he’s hit this pitcher before (“he has the best memory in the game,” says a Met coach), how he’s been swinging lately, even how to compensate for injuries (this is the guy who hit .423 in the ’73 World Series with a partially separated shoulder).

Statisticians like Bill James have proven beyond a doubt the importance of the first pitch—a strike can lower batting averages from 50 to 100 points—but pros have known it since the Cincinnati Reds were called the “Red Stockings.” “After the first strike,” Rusty Staub says, “you have to con-cede a little, and after the second, I don’t care how great your mechanics are, you have to concede a lot.” That’s where knowing the pitchers comes in—knowing about his stuff in general, his stuff today, his stuff the last inning (“sitting on the bench, I don’t always watch the other team’s at-bats,” Staub admits, “but when we’re up I’m always paying close attention”), what he can get over, what he likes to go with when he’s ahead in the count, when he’s behind, how he tries to get the batter to go for his out pitch. It’s two pros trying to set each other up.

When Rusty Staub talks about setting up a pitcher, after nearly 11,000 major league at-bats, he’s not talking about just one pitch he prefers, or one location—sitting on a fastball on a 3-1 count, for instance, is something you and I and Jose Oquendo can do—it’s knowing the situation, knowing, for instance, he’s going to get a 1-2 curve on the outside corner, and dumping a hit over the shortstop’s head.

Of course Rusty Staub isn’t about to reveal how he reads any of the pitchers in the National League, either their delivery or their pattern. With the instability of major league rosters, and the chance that someone on your team will soon be that pitcher’s teammate, he’s even reluctant to tell any of the Mets. “I have shared some of my knowledge in the past, but to my detriment,” Staub admits.

“Word almost always gets out, and then no one benefits. And the majority of players on the Mets—you won’t believe this—they don’t want to know what pitch is coming next, even if I’m positive. It’s beyond my comprehension.”

An example from the past, though, is Tony Cloninger. Had great stuff, 113 lifetime wins. “Tony always wore a long sweat shirt, even when it was 90 degrees,” remembers Staub, who never wears an undershirt. “After I’d hit against him a couple of times, I could tell what he was going to throw by how far his hand went into his glove at the top of his delivery. If he showed a lot of hand, it was a fastball, a little hand was slider, and no hand was curve—that long-sleeved sweat shirt made it easier to pick up.”

Does he ever see pitchers on the Mets tipping off their pitches? Rusty Staub grins. “Yearly,” he says, and won’t be more specific than that. What does he do about it? “I tell the pitching coach or the manager. I don’t think it’s my prerogative to tell the player personally.”

Most of history’s great hitters say they saw more fastballs in their last couple of years than in their first 15 years combined. “Those guys have learned to hit the hook,” Leo Durocher used to moan, “but they can’t get around on heat anymore.” But Rusty Staub, who just says “different pitchers try different things,” is still making a living with his bat, so he doesn’t want to talk too specifically about his hitting. After all, even pitchers can read. He’ll talk theories of hitting—lateral weight shift vs. bat head speed, etc.—with other players and coaches, but not for publication.

“There’s no one way, anyway,” says Staub, who once played for Harry Walker, the Charlie Lau of his day. “You can have the worst mechanics in the world and still be a good hitter. The most important thing is to under-stand yourself,” he repeats, “to learn what you can and can not do, to be able to adjust and compensate.” (In the Houston dome, not a power hitter’s paradise, he choked up on the bat, but dropped to the end when he was trad-ed to Montreal and hit half as many home runs in his first season there as in his six seasons with the Astros.)

“And so much of hitting is in your mind,” he goes on, “the way you visualize yourself, and you can’t teach that. Ted Williams always said he hit with a slight uppercut, but actually he had one of the great down strokes of all time. Sure he came up a little at the end of his swing, but in his mind that was the way he hit. In his mind,” Rusty Staub repeats, tapping his forehead with his forefinger.

Ask him about bats, though, and the vagueness vanishes. “Thirty-four inches for 22 years, 31 to 36 ounces, depending on the situation. I’ve been using a heavier bat lately. There’s a better chance of getting good wood.” Don’t get him started on wood—he’ll talk for hours about the decline in the quality of the wood. “Adirondack sent me good bats for 12, 13 years, but something went wrong. I use Worth bats now.” And just so you won’t misunderstand, “I’m not under contract to them,” he laughs, “I can say what I believe.”

Or ask him about being a batting coach, one of ex-manager George Bamberger‘s “inspirations” in 1982, and you get the quickest answer of all. “No.” Not a second’s hesitation. “No. I give advice very sparingly,” he says. “Some of the young players come to me, but ‘guys,’ I say, am not the hitting instructor.’ That one year as a player-coach didn’t work for me. The two things always interfered with one another.”

“Last year, if I saw something, I might go to Jimmy Frey, [hitting coach, who’s now manager of the Cubs] and say ‘you might watch so and so,’ or ‘what do you think about trying such and such?’ But talking to the players about mechanics? No, that’s not my job, that was Jimmy’s job, I wasn’t going to interfere.”

What about managing, though? Rusty Staub speaks carefully, making sure this comes out right. “I’d like to play for another two or three years, but then I can see myself managing under certain circumstances.” Such as? “I’d have to be convinced the organization really wanted to win,” he says vaguely. “I’d have to be convinced I had a viable position in the organization.”

This is not a guy who acts on whims. How about the current Mets? Darryl Strawberry? “He has as much talent as anyone I’ve ever seen come up. I don’t like to compare players, but he reminds me of Richie Allen. He has all the ability—how much of it he taps is up to him.” Keith Hernandez? “A bundle of energy—I really like him.” How about Mookie Wilson, an undisciplined hitter if there ever was one? “The most explosive player the Mets have had in a long time. He’s got a lot of big years ahead of him.”

Is he reading from a Mets press release? OK, Jose Oquendo? “I was surprised,” Rusty Staub says, “by how well he handled the bat last year.” Jose Oquendo? How well he handled the bat? A .213 hitter? Rusty Staub obviously isn’t going to say anything bad about anybody. But after you’ve talked for several hours with Rusty Staub, you realize he isn’t bullshitting you, he really believes everything he says. This isn’t a guy who lets “personal loyalty” cloud his judgment, this is a guy for whom “personal loyalty” is his judgment.

Still, sometimes it gets a little .. . aggravating. “I do as much charity as anyone, but certain people just push too hard. I can’t go to every Little League banquet I’m invited to,” he says in exasperation, and you can guess he’s taken flack from people who think he’s obnoxious for turning down their invitation, not knowing he’s already accepted four that week. “And it’s difficult being nice to fans in certain ballparks,” he goes on. “They don’t represent the majority, of course, but some of them pull your shirt or tear your clothes or spit on you. And I don’t even want to talk about the things that happen walking from the clubhouse to the bus.”

He’s more than willing to talk about the media, though. Sitting in his restaurant, looking over vouchers, signing autographs, getting up to take half a dozen phone calls, he explains why he’s so wary of the press. “Say I read in the papers that Davey Johnson said something or other. Now I don’t know if he really said it or not, if you get my drift. Some of the reporters in this town, they see a… ”

He’s getting frustrated just thinking about it. Looking for the right word, he suddenly slaps the table. “They see a table top and they call it a venetian blind. Sports writers wonder why it’s so difficult to get interviews these days—well, it’s because the players have been burned so many times.”

“One of the things that really riles me is when a reporter goes up to one of our young guys who doesn’t know the ropes and says, ‘did you hear what so-and-so said about you?’, completely fabricating some quote just to get a reaction. When I see that happening in the clubhouse”—just talking about it has him at the edge of his temper—”I go over and say, ‘excuse me, I’d like to talk to this gentleman in private for a moment, and I take the player aside and tell him, ‘keep your cool, don’t let him aggravate you into making a statement.’ Too many writers don’t want to tell the truth, they just want to sell papers. It’s intolerable.”

Rusty Staub is too much of a pro to decline interviews, but now you can see more clearly why he draws the line at his personal life. (And that of other players, too—keeping a teammate’s name off the record, he tells how that player’s family situation dramatically affected his play last year, “but the public doesn’t have any right to know anything about that.”) “I’m in the public eye in both my careers,” he says flatly, “and I’ll talk to anybody, anytime, anywhere about either one of them. But there are only 24 hours in a day, I’ve only got a couple left over for myself. I’ll fight to keep that private.” And when a 6-foot-2, 240-pound red-head looks you straight in the eye and uses the word “fight” in italics, you decide, well, not to pursue that line of questioning too vigorously.

There’s more to it than that, of course, because if Rusty Staub is simultaneously one of the most accessible and yet most mysterious players in baseball, simultaneously one of the most popular and most unknown, it doesn’t necessarily follow that there’s a huge discrepancy between his public image and his private personality. You can’t spend a lot of time with him, in fact, without suspecting that, no matter what he does in private, they are virtually identical.

He does let down the mask occasionally. Talking about the way he stood up to the Astro front office in that “day of mourning” incident, he says that some of his friends started calling him “The White Knight.” He seems instantly sorry he let that slip. “It’s no big deal, it’s just a nickname,” he blushes and quickly changes the subject. But what’s fascinating is that even a nickname given in private should so neatly parallel his public persona.

An even more revealing glimpse. Dave Kingman wasn’t the only Met player the fans and the press were down on last year. George Foster may have quietly slipped into the league’s top ten in homers and RBIs, but he was the runaway league-leader in disenchantment. You’d think Rusty Staub wouldn’t know that much about ups and downs—he never really had to struggle in his career, practically going from high school to the All-Star game—but Rusty Staub does know what’s important in his life. It’s not 3,000 hits but personal loyalty, not top ten stats but Christian virtues, not public cheers but private decencies.

“I’ve had all the accolades,” he says with a shrug. “That shit wears off.” So he got to know George Foster better, he got to like him better, exactly like Dave Kingman, precisely during his “time of duress.” It’s easy to be a great guy when everyone’s pouring champagne over everyone’s head. It’s a lot tougher when one of your teammates is going through a year of withdrawal and despondency. A couple of visitors to the Met locker room last summer may have noticed a small sign hanging on the wall of George Foster’s cubicle: “Life Is Fragile: Handle With Prayer.” What few people knew was that Rusty Staub gave it to him.

Ross Wetzsteon is a senior editor at the Village Voice and a star hitter for the paper’s softball team. He has also written on the arts for New York Magazine and Rolling Stone.