Introduction by Stephen Hanks

When the New York Mets announced their All-Time Team last week in honor of the franchise’s 50th Anniversary (Davey Johnson as manager over Gil Hodges? No freakin’ way!), it was no surprise that the first baseman was Keith Hernandez. But for Mets fans who go all the way back to the first days of the club (my first live game was at age 8 at the Polo Grounds in 1963), it was nice to see Ed Kranepool make the list of nominees at the position. Although he will eventually be overtaken by David Wright if the third baseman signs another long-term deal with the Mets, Kranepool still leads the organization all-time in games played, at bats and hits. In 1990, after years of seemingly being forgotten, the Mets honored Krane’s accomplishments by inducting him into the team’s Hall of Fame.

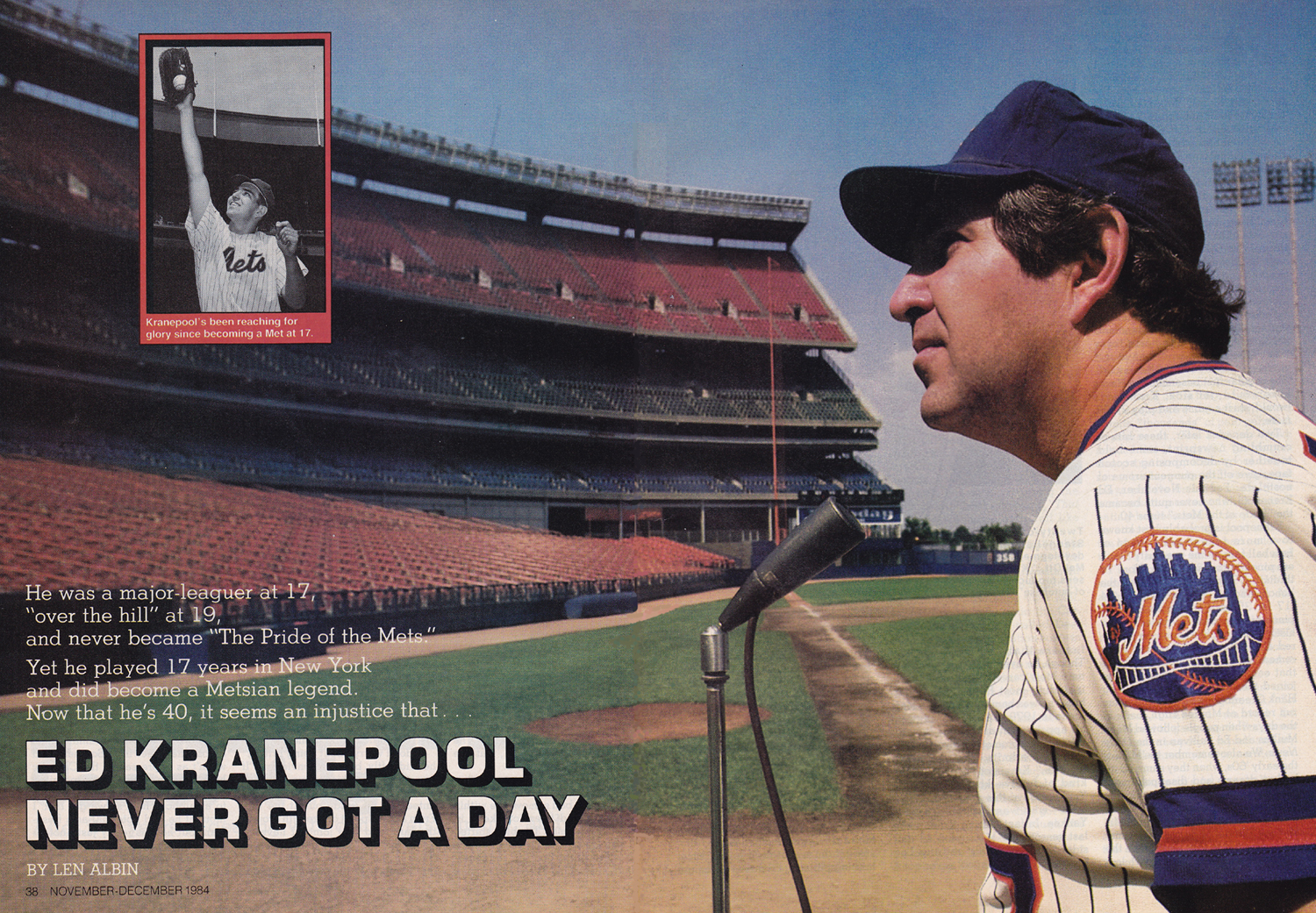

Back in 1984, when I was editing my newly-launched magazine, New York Sports, the former 17-year-old wunderkind from James Monroe HS in the Bronx had turned 40 and yet had never been recognized by the team in any kind of ceremony or “day.” At the time, the comedian Red Buttons was known for his hysterical routine on the Dean Martin Comedy Roasts, one liners that began with . . . “So and so never got a dinner!” Since Ed Kranepool had never gotten a “day” from the Mets, let alone a dinner, New York Sports decided to profile him in our story called, “Ed Kranepool Never Got a Day,” wonderfully written by freelancer Len Albin (who I had worked with at SPORT Magazine in the late ’70s). We thought an appropriate image for the story would be to have Krane, in uniform, stand in front of a microphone at home plate at Shea Stadium—but with nobody in the stands. Kranepool signed on to the idea and the Mets’ PR department graciously allowed us to set up the shot (below). We hope you enjoy this vintage mini-biography of the legendary Met, Ed Kranepool.

He was a major-leaguer at 17, “over the hill” at 19, and never became

“The Pride of the Mets.”

Yet he played 17 years in New York and did become a Metsian legend.

Now that he’s 40, it seems an injustice that . . .

ED KRANEPOOL NEVER GOT A DAY

New York Sports Magazine, November/December 1984, by Len Albin

METS SIGN SCHOOLBOY FOR $75,000, blares the 1962 headline in the New York Times . . . METS SHELL OUT 90 GRAND, NAB 17-YEAR-OLD PHENOM, announces The Sporting News

Mets Sign Schoolboy For $75,000, blares the 1962 headline in the New York Times…

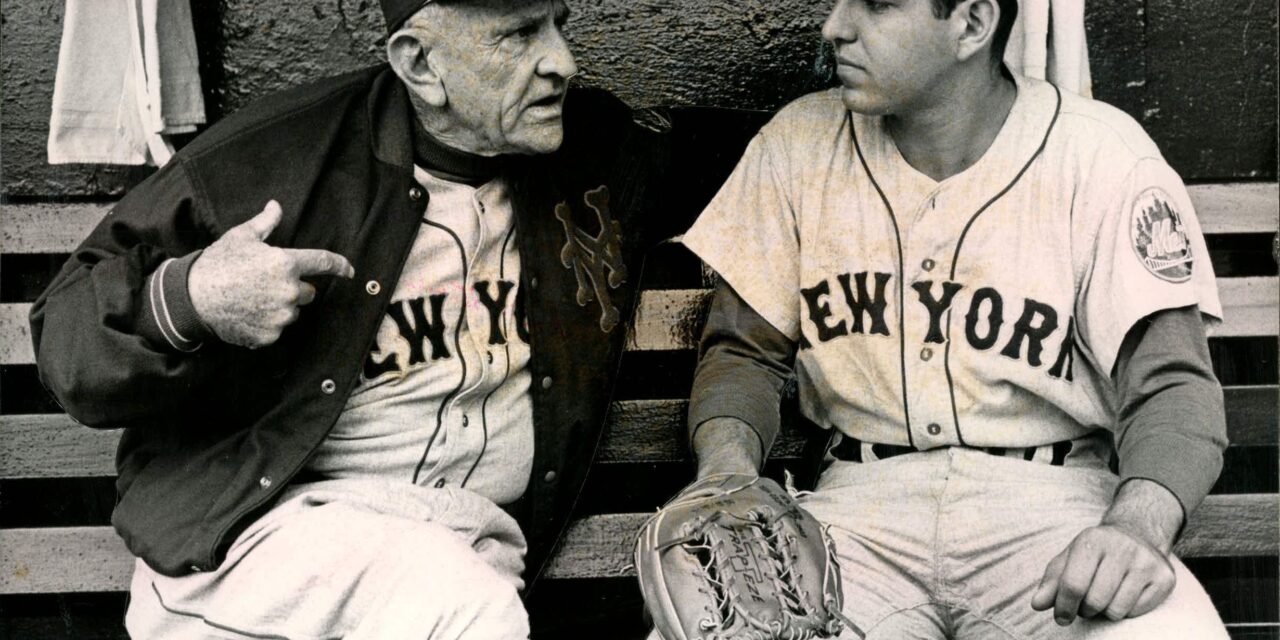

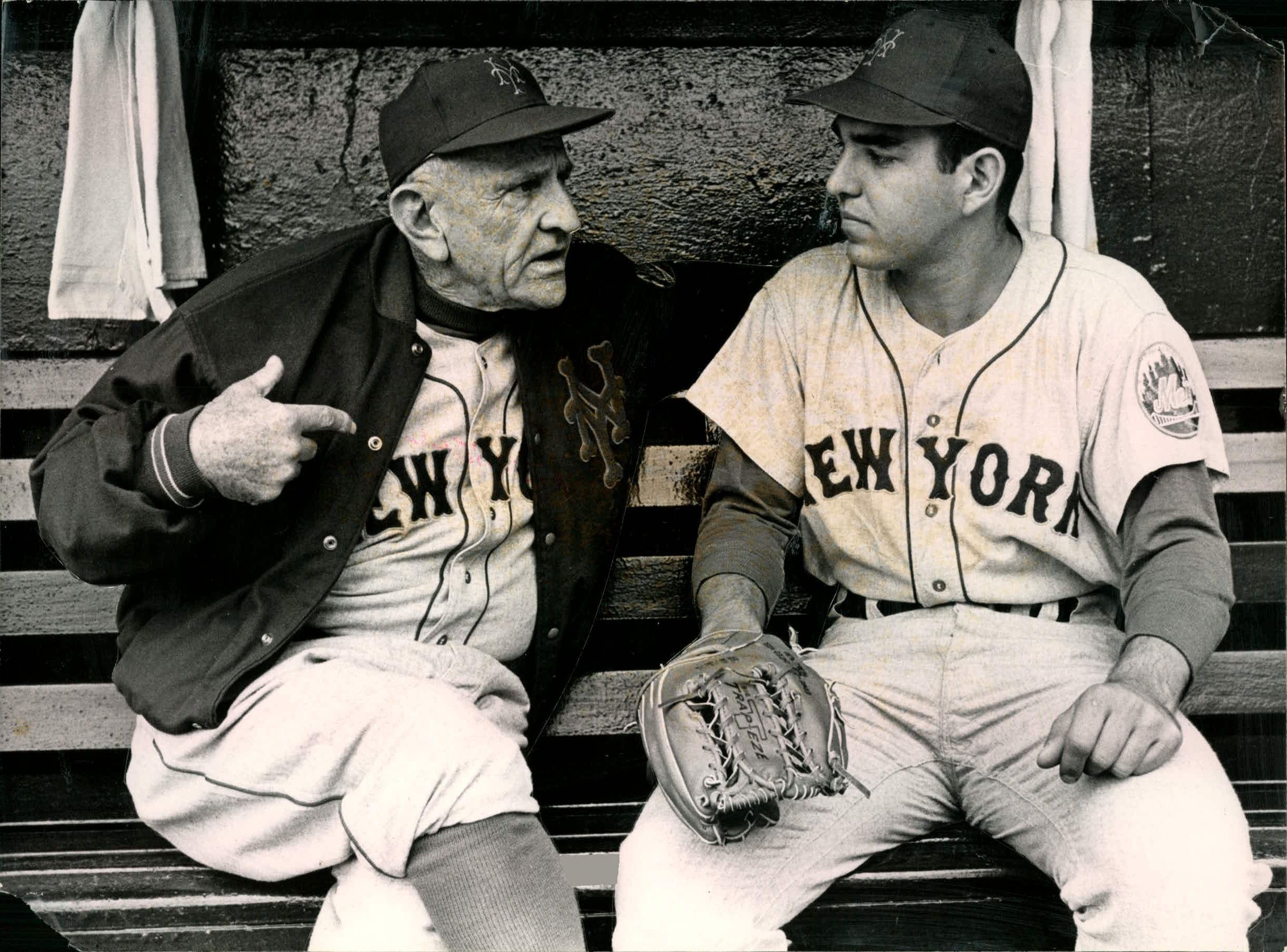

In the World-Telegram and Sun, manager Casey Stengel says Kranepool has “a lovely future” and compares his “kid genius” to another teenager who played in the Polo Grounds: “Now don’t get me saying that in one National League game I have spotted a new [Mel] Ott. But who can tell?” In the Journal-American, Kranepool says he looks forward to “playing 20 years in the major leagues.” And in the New York Post, James Monroe High’s Ed Kranepool is compared to Commerce High’s Lou Gehrig, another Bronx native who made it big playing for the hometown team. “As legend would have it,” wrote Post columnist Maury Allen in ‘64, “the Mets’ regular first baseman Tim Harkness would get sick; Kranepool [would] start a game and play 2,129 more.”

Two decades later, these bits of crumbling newsprint, some held together by decomposing scotch tape, give off the pungent aroma of nostalgia. For this November, Ed Kranepool, who never quite became the “Pride of the Mets,” turns 40.

Kranepool is probably best known to a more recent generation of baseball fans as the pre-Rusty Staub-era pinch-hitting specialist. From ‘74 through ‘77, he batted .477 off the bench, and his .486 average in ‘74 (17 for 35) still stands as the best pinch-hitting mark in major-league history (though, like Staub, he preferred a full-time role). But most of us remember Ed Kranepool fondly as that eager, oversized teenager who joined the Mets just after breaking Hank Greenberg’s 32-year-old home run record at Monroe High, back in the days when people followed Moon Mullins and Ed Sullivan in the Daily News. We also remember the Mets of the early ‘60s, when they summed up broken dreams and disappointment for everybody. In those days, Kranepool was a marginal Met, but he ultimately became as much “Mr. Met” as Stengel or Seaver. He somehow managed to last 17 years in the majors, yet he disappeared with less fanfare than the Daily Mirror. Though he eventually set seven all-time Mets career batting records, including most RBI’s, total bases, hits—he was banished from the Mets scene in 1979 like a horse way past his appointment at the glue factory. While Mets promotion director Tim Hamilton admits, “he was a fan favorite,” Kranepool never got the kind of festive kiss-off that the Yankees gave this year to Lou Piniella—who wasn’t even a career Yankee. In fact, during Kranepool’s last season, the Mets feted an outsider—the Cardinals’ retiring Lou Brock. But as Red Button’s might kvetch on the “Dean Martin Celebrity Roasts, “Ed Kranepool never got a dinner.”

“They didn’t even say goodbye to me,” says Ed Kranepool in 1984.

These days, Ed Kranepool has a regular job. He’s a salesman (and a minor partner) with the Lesjay Corporation of Long Island City, which sits on the waterfront of the East River. The firm occupies about 180,000-square feet of warehouse space in a musty, century-old building (that used to house a hamper factory) across the street from a clutch of low-income housing projects. Ed drives his beige Oldsmobile in each weekday from his condominium in Old Westbury. On this particular summer afternoon, local black kids greet their hero by rapping on the car as he pulls up. Kranepool rolls down the window to see about a truck blocking the Lesjay driveway.

“What’s this guy doing?” Kranepool asks. “Is he making a delivery?”

“What’s your problem, slick?” one of the kids says. “Just squeeze in. You know how you get into some tight pants, don’t you?” Kranepool eases the car around the truck and points with pride to having a new generation of fans. “When I first came here,” he says with a smile, “They couldn’t believe it was me.”

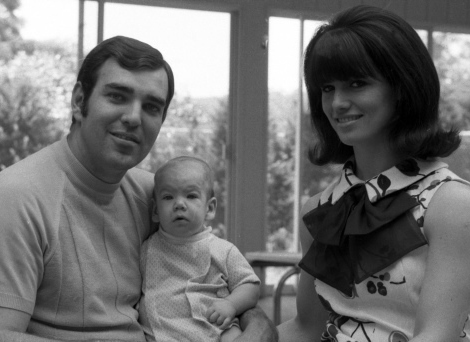

Ed Kranepool doesn’t seem much different from his playing days—just older. The deep creases at the corners of his eyes are well carved from years of squinting into the sunlight from the dugout shade. He’s developing a bald spot and a set of jowls that remind one of a mature Duke Snider. He’s also 10 pounds over his playing weight (205) and has diabetes, for which he takes daily insulin shots. Otherwise, he’s like many men his age: Divorced once, married twice, with three teenage kids (including two step-children) and a steady income. But he never jogs. For recreation, he likes skiing, boating, and working around the house. (Last year, he constructed a tri-level outdoor deck in his backyard; this year, he built a 1,200 square-foot basement.) But he rarely visits the ballpark. “I haven’t watched nine innings since I retired,” Kranepool admits. “The last time I did that I was playing.”

Kranepool’s company manufactures “point-of-purchase” displays, one of the growing specialty areas in consumer marketing. “It’s a tremendous field,” Kranepool crows. “Some of these companies have tremendous budgets.”

Among the products on exhibit in Lesjay’s makeshift lobby (really a finished basement decorated with a plastic azalea bush) were the plastic storage bins that hold “Danskin” pantyhose, a “Redken Skin Care” cosmetics display, and the plastic beer signs with the “moving” twinkly lights seen in liquor stores. In a word, they’re in plastics. Kranepool pulls out one of the tiny plastic components of another stocking display and animatedly explains that it’s made through the process of “injection-molding.”

“See, you have the tools and you make trays and stuff like that,” he says, slipping the plastic drawer back into place. “That comes out of molds and stuff like that.”

The point-of-purchase display biz is just one subsidiary of the Kranepool business and investment “empire.” For a guy who didn’t attend college, he’s doing very well. He’s putting up a hotel in the Catskills near a ski resort called “Deer Run,” and he owns a vacation home in the Poconos. On the side, Kranepool is a partner in a sports-marketing company called “Sports Plus.” The angle here is packaging business junkets for executives-coordinating hotel and airline reservations, and events—with a theme in mind. For example, when Xerox introduced its new “l0K” model copier, Sports Plus arranged 10K mini-marathon races in the Caribbean for the corporation.

“It worked well for Xerox because they got their name out—the 10K—through the race,” Kranepool says. “These are the ideas you gotta come up with.” He’s also got $50,000 sunk in the Tri-Cities Single A ball club in the Northwest League. “It’s in the state of Washington,” he relates. “Pasco, Kennewick, and something else. I don’t know. Three cities. I bought the Walla Walla franchise two years ago and moved it to Tri-Cities the same day I bought it. They didn’t know what was going on, I move so fast.”

Being involved in deal making and investments is nothing new for Ed Kranepool. Since his pro career began, he’s seized moneymaking opportunities the way Pete Rose goes after hits. While a player, he co-owned with teammate Ron Swoboda a restaurant in Amityville, New York called “The Dugout.” In the off-seasons of ‘63 to ‘68, Kranepool worked as a licensed stockbroker with the Manhattan firm of Brand, Grumet, and Siegel, where he traded securities for over 150 clients, including Met teammates Dennis Ribant and Hawk Taylor, and met first wife Carol, a secretary of one of his bosses. In ‘71, he did a guest shot on Sesame Street, helping teach kids how to count to 10. And he would spend much of the fall and winter on the banquet circuit, making, as he admits, “thousands” of paid personal appearances. The Sporting News noticed this in early ‘67:

“In his pre-camp training, Kranepool takes sauna baths, works with weights and plays paddle ball. He needs those workouts to counteract all that good eating he does at the many dinners he attends to promote good will for the Mets . . . Kranepool had no fewer than 13 January banquet dates and 10 in February.” On another occasion, Kranepool took a USC-sponsored 10-day trip to Thule Air Force base in Greenland. This year, when the Mets asked him to “computer manage” the 1969 Mets for the August 31st Computerland promotion, he insisted it couldn’t be just for fun.

“It was a commercial venture and somebody was gaining from it,” Ed reasons, “And I wanted Ed Kranepool to gain from it. I’m gonna take time away from myself and my family. I wanna get remunerated for it.”

So Kranepool’s fat baseball pension probably doesn’t make much difference. Though he isn’t making a 1984 ballplayer’s bucks, he says he’s comfortable and happy. His flair for the dollar has ensured him another “lovely future.” In fact, shrewd planning for the future has always been one of Kranepool’s prime concerns. Reporter Jack Lang once remarked in The Sporting News that Kranepool was “an extremely security-conscious” player. But, as Kranepool is quick to point out, owners weren’t exactly throwing around million-dollar contracts, as they do today.

“When a guy gets two, three, four million dollars,” he observes, “You don’t have to be very smart to prepare for your future. If you have that much cash, you just put it in the bank and you’re in pretty good shape, living off the interest.” But why does he have a seeming preoccupation with the almighty buck? “Hey, nobody gives you anything in this world,” he philosophizes. “So you gotta hustle.”

Some in the Met organization felt that had Kranepool hustled as much on the field as he did off it, he just might have become Casey Stengel’s new Mel Ott. But baseball stardom wasn’t his only career goal. “He was consumed by baseball,” recalls his ex-wife Carole, “but he also had a drive within him to make money. Coming out of the Bronx, he had nothing. He was very poor. And he had this tremendous desire to be successful. And it was through baseball that he would achieve that success.”

Before Ed Kranepool’s smooth left-handed stroke convinced scouts that he was going to be “the gentile Hank Greenberg,” he spent his Bronx boyhood obsessed with baseball. Since Ed’s father had been machine-gunned in France during World War II four months before Ed was born, his Little League coach and neighbor, Jim Schiaffo, taught him the game. When young Eddie got a baseball glove for Christmas of ‘55, he asked Schiaffo to come outside and hit him a few grounders. “My wife looked at me,” Schiaffo recalls. “I looked at him. What could you do? He had no father. We went out to the Whitestone Bridge and I hit ground balls to him on Christmas morning. It was as cold as a witch’s backtail. But I loved it, because this kid, he ate, drank and slept baseball.” Then there were the off-season “skull practices,” during which Eddie would stand with a bat over the home plate that Schiaffo had chalked under the Kranepool’s living room rug.

“I’d say, ‘Eddie! An outside pitch coming!’” Schiaffo remembers, ‘“What do you do with it? Left field! . . . Inside pitch! What are you gonna do with it, Eddie? Remember! Bail out! Right field! . . . And keep the head straight! The head’s gotta be straight! The arms take the body around. The body don’t take the arms around.’ That’s what I used to tell him. And kept tellin’ him, and tellin’ him, and tellin’ him.”

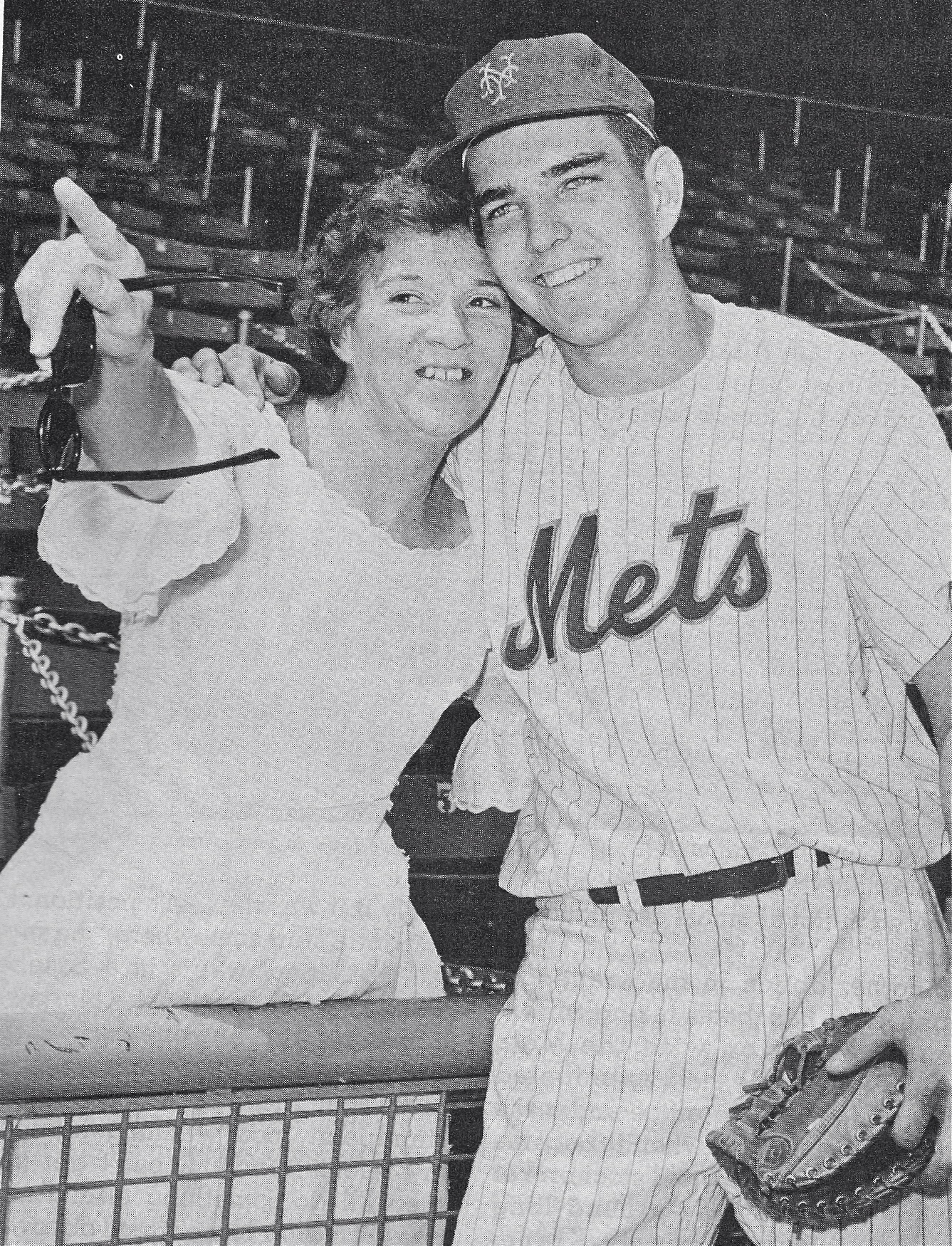

By his mid-teens, Kranepool already has a star’s confidence. Throughout his sandlot days, he wore number 7, just like his Bronx idol, Mickey Mantle. In high school, he called himself “The King”—announcing, “The King’s home” to his mother when he swung open the front door. And with his $85,000 bonus money from the Mets—who were obviously counting on him to be their first home-grown hero to put fannies in the seats—he bought himself a fancy car: a white Thunderbird. (Actually, Eddie wanted a sportier Corvette or Jaguar, but he found he couldn’t squeeze his hulking 6-3, 205-pound inside them.) Then “The King” whisked his mom out of their apartment in a three-family house on Castle Hill Avenue in the Parkchester section, and bought an eight-room home in White Plains. He shelled out even more for new furniture, a set of dishes, and a Magnavox hi-fi that cost over $300. (In the Daily Mirror, a smiling Mrs. Ethel Kranepool is pictured sitting at her new sewing machine).

But within two years, astute observers could detect important clues about the young Kranepool’s baseball future. In ‘63 and ‘64, he had to be demoted briefly to the minors, while his beloved number 7 was taken, in succession, by Sammy Drake, Elio Chacon, and Amado Samuel (while Ed settled for number 21). When he pulled a leg muscle in spring training in ‘64, Casey Stengel complained, “You would think you could be 19 and in shape.” And on Opening Day at Shea that year a now immortal banner asked the ultimate question about this underachiever: IS ED KRANEPOOL OVER THE HILL?

“Some guys get their cheap fun going to the ballpark,” Kranepool says today, still annoyed after all these years. “I don’t like anybody who makes fun of anyone else’s inadequacies.” But he soon turned the jeers into cheers. In ‘65, Kranepool made the All-Star team as the token Met after a superb first-half of the season; he was a key player in the Met pennant-winning years of ‘69 and ‘73; in ‘74, he led the league in pinch-hits, and would step to the plate to chants of “Ed-die, Ed-die.” Kranepool now looks back on his career with some pride, insisting that during his last “seven or eight years” he was as tough an out as anybody in baseball. “Obviously I was productive,” he says. “Otherwise I couldn’t fool ‘em for 17 years.”

But he wasn’t that productive. His lifetime batting average was .261, and he averaged only about seven home runs per year. On the basepaths, he ran like a retired furrier chasing a mugger. And he wasn’t exactly Nureyev in the field, either. Once, when Kranepool made a diving catch in left field for the Mets’ Triple A team (where he’d been demoted in. 1970), the play was viewed as a supernatural event.

“If Ed Kranepool makes a catch like that,” said pitcher Bill Denehy, “I know I’m going to pitch a no-hitter.” In retrospect, Kranepool’s most spectacular achievements—aside from his longevity—may be two items already enshrined in the trivia archives. On the weekend of May 30-31, 1964, Kranepool played 50 innings within 33 and a half hours—the first 18 innings in a doubleheader in Buffalo (then the Mets’ Triple A team), and 32 more innings in a doubleheader at Shea against the Giants, which included the famous 23-inning nightcap. (Could Lou Gehrig do this?) Ten years later, Henry Aaron used a 33-ounce, 34 and a half-inch Ed Kranepool-model 220-A Adirondack bat to beat Sadaharu Oh in a home-run-hitting contest in Tokyo.

So, why didn’t Ed Kranepool do as well with the same bat? “They shoulda left me in the minor leagues to develop, and they woulda got a better player out of it,” he says, echoing the arguments that were raised then. “A young guy at 17 isn’t physically ready for the major leagues. Nor was a 17-year-old ready, in Kranepool’s opinion, for the Hall-of-Fame-caliber pitchers lurking in the National League in the mid-1960’s—like Sandy Koufax, Bob Gibson, Juan Marichal, and Don Drysdale. There was also knuckleballer Phil Niekro to contend with (Ed’s least favorite pitcher), and some “wild” fastball pitchers.

“Koufax could be a comfortable oh-for-four,” Kranepool recalls. “Bob Veale? You’d stand up there and check your drawers at the end of the night.”

That he didn’t get to develop in the minor leagues was partly Kranepool’s own fault. He wanted to be rushed to the majors. As he told Barney Kremenko of the Journal-American in ‘63, “I chose the Mets not only because they offered me enough money, they also presented an opportunity to make the big leagues in the shortest amount of time. For my career that was very important.”

By 1970, Mets general manager Bob Scheffing found himself paying a fat $35,000 a year to a player who, in Scheffing’s words, “has the unhappy knack of hitting a lot of fly balls on bad pitches.” But Kranepool blamed his own shoddy performance on manager Gil Hodges’ platoon system. He wanted the chance to prove he could be a productive everyday player, eight years into his career.

“He’s been to bat nearly 3,000 times in the majors,” Tom Seaver observed. “That’s not a chance?”

As owner Joan Payson’s favorite Met, Kranepool survived. And once he became an eight-year veteran in early ‘71, he couldn’t be demoted without his permission. The only threat was being released but Kranepool kept the vultures at bay by pinch-hitting so well. Kranepool eventually became part of the Mets “family.” When he got his final Mets contract, a three-year deal at $100,000 per year, he didn’t haggle with Board Chairman M. Donald Grant. Instead, he gave Grant a signed blank contract, and Grant—like a kindly godfather—filled in the numbers. The sweet, secure contract enabled Kranepool to observe first-hand what in his view was the “ruination” of the Mets. “Joe McDonald [then GM] got rid of Seaver, he got rid of Koosman, he got rid of Tug McGraw, he got rid of everybody on the ballclub,” Kranepool says bitterly. “There was nobody left when I retired. I was down to myself.”

When Ed’s three-year contract expired after the ‘79 season, the new Mets management rejected his demand for a two-year extension. But Kranepool still wasn’t going anywhere. Though he was a free agent, he privately told other clubs not to draft him—at least not if they wanted to pay a measly 100 grand.

“What’s the big deal?” Kranepool reasons. “If I’m going to make $100,000 in New York, or even $120,000 in, let’s say, Minnesota, what benefit am I going to gain? I’m not gonna see my family for three months. I have my own living expenses in Minnesota. My businesses that I have in New York go down the tube. Where do I gain? I lose money.” So Kranepool, with the timing of a hitter in a slump, left baseball just as the free-agent market exploded. “Had I known that the owners were going to be so free with their dollars, I’d still be playing today,” he says. “Because the salaries are tremendous. I didn’t have a crystal ball, so maybe I’m not as smart as I thought I was.

Another option in the Kranepool game plan had been taking an executive position with the Mets management. He had anticipated going into the front office under the Payson regime, but when it became apparent that kindly old stockbroker Grant wouldn’t stay around long enough to give him one, Kranepool—undeterred—made inquiries about buying the Mets.

With the money of Bob Abplanalp, the inventor of the aerosol spray device and a buddy of Richard Nixon, behind him, Kranepool approached the Mets at the end of ‘79. If the deal had gone through, Kranepool would have likely become general manager. But Mets owner Lorinda deRoulet (Payson’s daughter) never took them seriously. “It seemed like she wanted to sell to the Doubleday people all along,” Kranepool recalls. “Probably because they were from her social surroundings.” On the other hand, deRoulet might have been astounded by the chutzpa of that Kranepool, a mere employee, trying to buy the Mets. In fact, at the same time, he was still quibbling with management about his 1980 contract.

But if the Mets were to offer Kranepool a front office job today, he would definitely consider it, especially if it was the GM’s position. (“If you gotta start somewhere,” he says.) All Kranepool wants in a baseball job is one that won’t take him away from New York, and one that will pay decent money.

“I love baseball,” he says, “But I love it from a financial standpoint, too. I wanna get paid for my talents, and if I can’t get paid then I’ll do something else. And it doesn’t matter to me what I do to earn a living.” So, if George Steinbrenner asked Ed about joining the Yankees’ front office he’d consider that, too. “I don’t feel an allegiance to the Mets anymore,” Kranepool says. “Loyalty went out the window the day they didn’t sign me.”

When Ed Kranepool drives by his old Bronx sandlot stomping grounds, he notices that no longer are kids playing baseball there from morning ‘til night, as he did as a teenager. “I think kids are missing out,” he says, wistfully, “and I don’t understand it, ‘cause all they gotta do is read the paper and see the salary structure in sports. There’s gotta be more of an incentive to play. Because sports, I guess, is number two economically. Number one would have to be, I would imagine, the entertainment field.” Yes, times have changed.

And so have the Mets—but Kranepool never got too hysterical over this old team’s run at the pennant this summer. When he did tune in a Mets game, his mind tended to fill with memories of days gone by. “Your life flashes in front of you,” he says. “You remember the good old days and what you had.” Most of all he savors that ticker tape parade held on lower Broadway for the ’69 World Champions. Kranepool still gets calls from Art Shamsky, and keeps in touch with Tommie Agee, Ron Swoboda, and Tug McGraw. He’s even become “good friends” with Tom Seaver, even though Seaver was once one of his harshest critics.“Tom Seaver matured when he learned to accept adversity,” says Kranepool, who’s older than Seaver by nine days. All of a sudden he became a .500 pitcher with the Mets and he had to swallow a little crow. He wasn’t the darling of everybody, and he knew what it was like to suffer. He became a better person for it.”

Of course, after playing 17 years for the Mets, Ed Kranepool knows plenty about suffering; adversity was what the Mets were all about, so after a while, you develop a taste for crow. But now that this Metsian legend has hit 40, doesn’t nostalgia dictate that Kranepool have a taste of glory, or at the very least chicken, at a dinner in his honor.

“I don’t need them to give me a dinner,” Kranepool says simply, but not very convincingly. Jim Schiaffo, the man who once hit Eddie grounders at Christmas, feels differently. “I’m personally disappointed,” says Schiaffo about the Mets’ oversight. “Seventeen years with the team, and no recognition. They didn’t even buy this kid a sport jacket, for God’s sake.”

“I hope that someday they will give him a day,” says ex-wife Carole. “I think it would take away some of the bitterness he feels about leaving the team. He’s hurting.”

But whatever happens, we can still remember Ed Kranepool simply—and fondly—as the almost “Pride of the Mets.” Once, he was a promising young star who was going to replace Tim Harkness at first base and play 2,130 consecutive games like Lou Gehrig. Though they weren’t consecutive, he eventually came only 277 short.