It has been one week since the MLB team owners locked out the players (MLBPA), in a move the owners termed “defensive”, and whose purported intent was to move the negotiations forward for a new Collective Bargaining Agreement. So far, the lockout has not achieved its desired endpoint, because the two sides are not even talking (at least not to our knowledge).

From a timing perspective, with the focal point being an on-time start of spring training, there is still an opportunity for an agreement to come together with no impact on the 2022 season. The functional deadline is probably around February 1, to give remaining free agents a chance to learn where they will be playing, trades to be made, and players to have a reasonable timeline to report to their training sites by mid-February.

Should the lockout persist into February, at a minimum spring training will be shortened, which could impact players’ (especially pitchers’) level of preparedness for the season. If the lockout goes into March, the season will be shortened. This is the outcome no one wants, especially the fans. A shortened season would not be unprecedented in baseball.

How did the MLB owners and the MLBPA get to this point? History tells the story. As we know, those who do not heed the lessons of history are condemned to repeat it. Let’s take a top-line look at the history of labor relations in MLB.

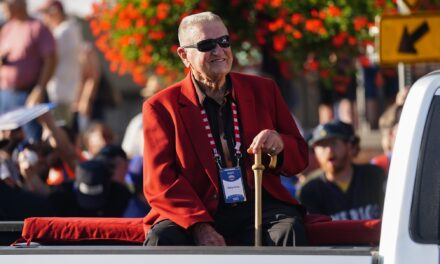

Prior to the 1970s, the owners held all the cards. Players were bound to their teams, and teams could pay the players what they felt was reasonable when contracts ran out. Players had two choices. Take it or leave it. Ralph Kiner told the story of being given a pay cut after leading the league in home runs. He was told the team finished last with him, and it could do so without him. In the 1970s, the players began to push back.

1972: The players went on strike for the first time. The issue was the owners’ contribution to the pension fund. The owners refused to give in, hoping to damage or break the union. The strike was settled in 13 days, with the players getting what they wanted. In total, 86 games were lost at the beginning of the season. The games were not made up, and teams played different total numbers of games.

1973: Owners locked out the players in spring training over the issue of salary arbitration. The result was a new CBA that included salary arbitration to be decided by a neutral arbitrator. Spring training started and no games were lost.

1976: This was the big one. Union lead Marvin Miller challenged the reserve clause that bound players to teams, and he won. Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally became the first free agents. Owners angrily locked the players out of spring training, but matters were resolved in March and no regular-season games were lost.

1980: With the CBA about to expire, players went on strike in spring training, canceling the last week. Further labor strife was avoided, temporarily. The 1980 season played without interruption. Free agent compensation remained an open wound.

1981: The players went on strike in June and two months of the season were lost. The issue was free agent compensation, still unresolved from 1980. The agreement reached allowed for teams losing a free agent to select a player from a pool of unprotected players (this cost the Mets Tom Seaver in 1984). The union accepted that, although the compensation system would have somewhat of a drag effect of the desire to sign free agents, the drag would be modest.

1985: The players went on strike for two days in August. The issues were the pension fund and salary arbitration (both repeats).

1990: The owners locked the players out of spring training over free agency and arbitration. The season started a week late, but all games were played.

1994: This one was baseball Armageddon when the players went on strike in August and the game was shut down until the following April. At one point, President Clinton had both sides at the White House, and they still could not reach an agreement. That’s how deeply the animosities ran.

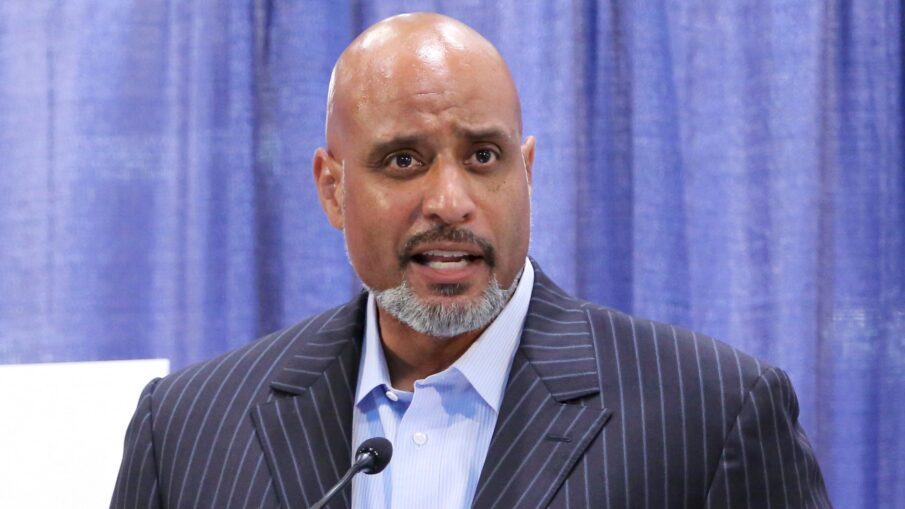

The animosity and mistrust are palpable during the current negotiations (or lack of negotiations). The names have changed over the years, from Bowie Kuhn to Bud Selling, from Donald Fehr to Tony Clark, but the tonality between the players and owners remains the same.

The tension was on display last year when the two sides could not agree on the length of the season, when it should start, how many teams would qualify for the postseason, etc. All of this does not bode well for an expeditious resolution, a new CBA, and the resumption of what had become an exciting offseason.

At times, good and enduring ideas can come from times of unrest. To look at this offseason positively, the free agent frenzy that took place in the two weeks before the lockout was captivating and had the sports world talking about baseball.

Some have suggested establishing a trade deadline in the offseason. That would also push free agent signings (similarly to what we just experienced), as teams will need to work against a deadline to solidify their rosters. Maybe the two sides can agree to something like that in the new CBA.

Then again, given their history, the odds seem to be against it.