The Dodgers signed Shohei Ohtani to a 10-year, $700 million contract on Saturday. By Monday night, it was reported Ohtani would earn just $20 million over his playing years. He’ll get the rest of the $680 million once his 10-year contract with the Dodgers is done.

That, then, allows the Dodgers more flexibility under the competitive balance tax rules of the current collective bargaining agreement. They’ll report just over $46 million in CBT hits over the next 10 years rather than $70 million. That gives them more room to sign good players to massive deals without being penalized with luxury tax payments. (It lowers the present-day value of Ohtani’s deal down to around $460 million, which is probably more fair for a pitcher who is coming off Tommy John surgery but can also hit 45 homers a year.)

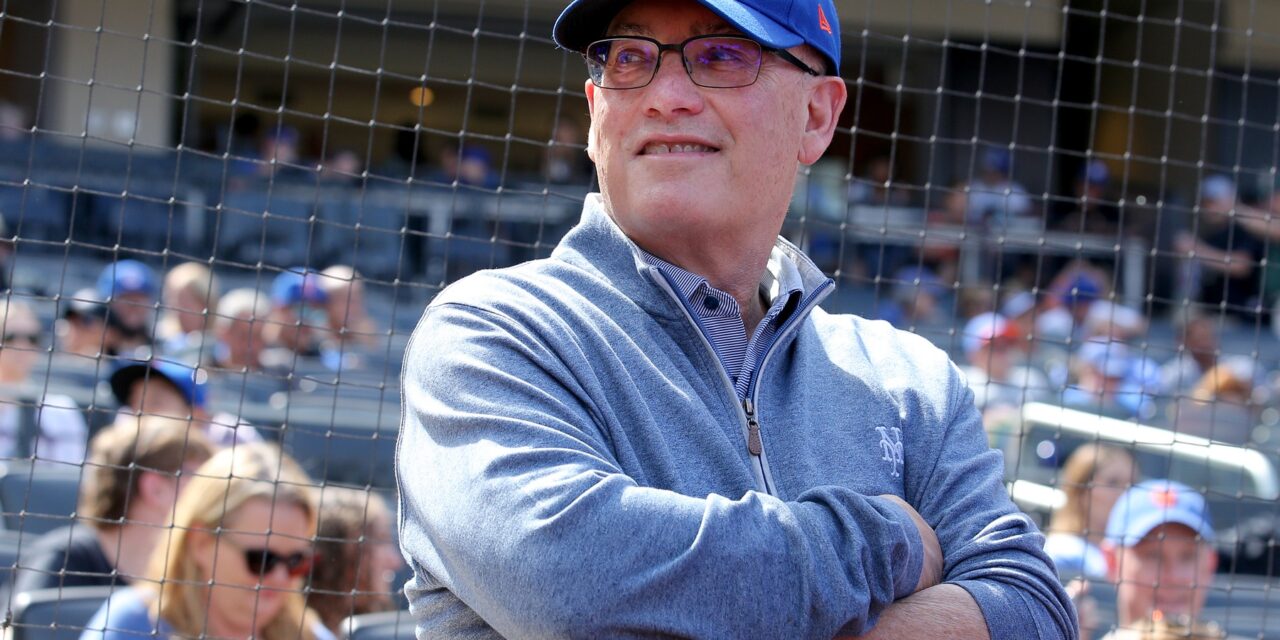

Shohei Ohtani. Photo by Roberto Carlo

All this leads a Mets fan to believe… can Steve Cohen, the richest owner in baseball, take advantage of this?

The current rule that deferrals cannot be capped will surely be challenged in the next CBA. But for the next three years, owners with lots of capital and the ability to take on long-term debt can dip into next decade’s finances to ease today’s. (Owners love this arrangement.)

That sounds like Cohen.

Of course, you’ll have to have a player willing to play the game. Players largely don’t like to defer money. Ohtani can do this because his endorsements alone are enough to let him live in Los Angeles alongside the richest. Not every player would be comfortable making a fraction of his contract now and most of it in retirement. And not every player will earn the hundreds of millions of dollars necessary to make mass deferrals worth it to help lower the CBT number in the interim.

Surely players wouldn’t defer money as severely as Ohtani did. (He’s getting just 3 percent of his total contract over the next 10 years.) But would a player take 20 percent over eight years and then 80 percent of the next eight to help his team sign more players under the current rules?

Francisco Lindor has already deferred $50 million of his $341 million. (That’s just under 15 percent of the total money.) With the goal to win and sign good players over the last eight years of his deal, what if he deferred another $200 million and reduced his CBT number? Could Pete Alonso play this game with a future extension?

Or, say, next offseason, Juan Soto commands a deal north of $500 million. Whatever owner ultimately may not be able to stomach an Ohtani structure. But what if Soto is cool with deferring $575 million of a $650 million deal until after his playing days? Whatever team signs him could work wonders under the current tax rules. (The deferrals would lower the present-day value to something just over $400 million, but if Ohtani really only got around $460 million, can Soto really expect to get more?)

These are just theoretical numbers, with theoretical players who’d buy-in, and, theoretically, an owner who’d be willing to tack on all that debt for down the road.

Maybe Ohtani—like he is on the baseball field—is an anomaly.

There’s also the argument that players shouldn’t have to take on the pressure of easing the luxury tax burden. Most owners use the CBT as a salary cap to stay far away from, when in reality, many can afford to spend up to it.

What the Dodgers and Ohtani did was creative. Steve Cohen couldn’t have been the first owner to–within the rules–mess with CBT numbers like the Dodgers have. The highest tax threshold is named after Cohen, after all. But now that the limitless deferral rule has been adopted in the most extreme way, you’ll have to figure Steve Cohen will find a way to take advantage of it.