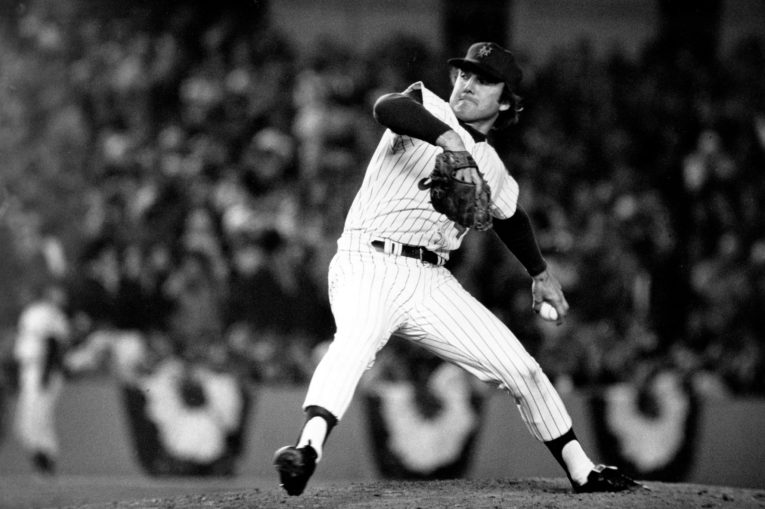

Over the next six weeks, we’ll look back at the 50th anniversary of the Mets’ 1973 National League pennant-winning team by examining the most inspirational figures of that remarkable run. We start with the man who unofficially initiated the team’s comeback from last place to first and officially coined the phase associated with that season.

In July 1973, Tug McGraw’s career approached a crossroads. His ERA after 41.1 innings was a sizable 6.20. He had nearly as many blown saves as converted saves. His team was also at a breaking point.

Following a July 7 game in which the left-hander relinquished a late lead against Atlanta, the Mets dropped to 34-45 and 12.5 out in the NL East. As local newspapers polled fans on who should take the fall, team chairman M. Donald Grant held a clubhouse meeting in which he emphasized his faith in the Mets to turn matters around.

During this collective vote of confidence, McGraw belted out the phrase that would become this club’s trademark. Many players laughed off his “Ya Gotta Believe” rallying cry as nothing more than typical behavior from their left-handed free spirit.

Grant wasn’t so amused. He later told McGraw his job was on the line. Tug eventually turned his own words into action, and the rest of the Mets would subsequently turn McGraw into a prophet. New York’s climb from last place in late August to the National League pennant in October paralleled his own revival. Over the last six weeks of the regular season, Tug made 19 appearances, saved 12 games, won five, and had a razor-thin ERA of 0.88.

In the Mets’ final 25 victories, which allowed them to take the NL East by 1.5 games, McGraw factored in 17 of them. He also finished off the NLCS clincher as well as two key World Series victories. No player better epitomized, closely mirrored, and more strongly associated with the 1973 Mets season than McGraw.

He began 1973 with a 1.32 ERA and five saves through May 3, then reversed course—blowing seven of 13 save chances and allowing 32 runs in 33 innings. The Mets tried to get McGraw out of his massive funk by moving him into the starting rotation. That failed, too. But Tug’s positive thinking and his proven abilities led him to regain his talents and lift a floundering team ravaged by injuries.

New York benefited from the mediocrity of its divisional competition and the timely return of many key players. The Mets remained in the cellar in late August, 6.5 games out, before making their ascent. Tug was never better than at the end. Beginning on August 22 (when he still had a 5.45 ERA), he allowed just four earned runs over the next 41 innings. He notched 12 crucial saves, including one at foggy Wrigley Field on October 1 that brought this unusual NL East race to a close.

McGraw temporarily took a backseat to the starters in the NLCS against Cincinnati. Seaver, Jon Matlack, and Koosman each went the distance in their respective outings. His workload increased significantly by Game 4. He worked 4.1 scoreless—but stressful—innings, tiptoeing out of jams in the eighth and ninth and aided Rusty Staub’s spectacular catch in the 11th. A 1–1 deadlock held until Harry Parker surrendered a Pete Rose 12th-inning homer.

The Mets’ attempt to claim the NL pennant was delayed just for a day. Just as he did in the division clincher, Tug spelled Seaver, this time with the bases full and the Mets holding a 7–2 ninth-inning advantage. After a pop-out, McGraw induced a Dan Driessen grounder. He ran to cover first base, took the toss from John Milner, and touched the bag while a rabid sea of humanity engulfed the Shea grounds.

The frenzy that followed the final out symbolized the frantic ride of the last six months, with McGraw in the front car of the roller-coaster. Contrary to his rather light workload in the 1969 Fall Classic, McGraw logged 13.2 innings during the ’73 series. Almost half came in Game 2—the longest World Series contest to date. When he took over in the seventh, the Mets held a 6–3 lead. That advantage evaporated by the ninth, as Willie Mays’s infamous stumble in center paved the way for the tying runs.

He remained on the Oakland Coliseum mound into the 12th in a scenario now reserved for baseball’s stone age. McGraw had a more conventional two-inning, one-hit, no-run outing in Game 3 at Shea, earned a one-night breather, then got the final eight outs to save a 2–0 Game 5 victory.

The Mets were a win from scaling the base of a mountain to the summit in a matter of two months. But they wouldn’t get to the summit. The Mets lost both in Oakland, with a brief McGraw appearance in Game 6 to solidify a 1.93 ERA over 13.2 postseason innings.

Tug McGraw was dealt to the Phillies following 1974, where he’d close out a World Series victory six years later, but not before leaving a lasting impact on Mets history.