Mike Piazza and Mariano Rivera. The greatest hitting catcher and the greatest closer. It was the bottom of the ninth at Shea Stadium in Game 5 of the first all-New York Fall Classic since 1956. The Mets trailed the Yankees 4-2 on the scoreboard and 3-1 in the series. With a man on base, the tying run was at the plate — represented by a person easily capable of delivering such a swift change in momentum.

When Piazza swung at Rivera’s 0-1 pitch, the Shea Stadium clock read 12:00 a.m. Shortly after, midnight would also come down on the franchise’s most successful season in more than a decade. Piazza’s drive went to deep center field. Mets fans who primarily populated the 55,292 in attendance were hopeful.

Yankee fans who took up a portion of the capacity crowd were likely fearful. Everyone watched as the ball cut through the hazy Queens sky. Bernie Williams drifted back and stopped short of the warning track to make the game-ending, series-ending catch. The Mets wound up a few wins short of a title — one claimed by their cross-town rivals and celebrated on their home field.

There is no shame in losing a World Series. But losing it to the team that occupies the same city and now had won three championships in a row and 26th in total, it was certainly a bittersweet feeling. Especially painful was the fact that the Yankees’ five-game triumph was closer than the final outcome indicated, with each contest decided by two runs or less.

To make the Subway World Series a reality, the Yankees had to overcome seven straight losses in September and a scare in the Division Series before beating Seattle in the ALCS. Led by an ex-Met player and manager along with a roster built primarily through the draft and savvy transactions for veteran players, the “dynasty” label was beginning to fit.

This meeting of New York teams created heightened anticipation, even by New York standards. It was a happening commonplace during the 1940s and 1950s when three prolific local franchises consumed the baseball landscape and it was a scenario that nearly came true the year before — when the Yanks won it all and the Mets lost out on the pennant to the Braves.

Most considered the Yankees as favorites, but Benny Agbayani thought otherwise. Asked by Howard Stern how many games the series would last, Agbayani said five. “And we’re going to win it.” He told noted Yankee fan Regis Philbin the same thing: “Mets in five.”

His reasoning? “Five is our lucky number,” he said.

Saturday, October 21 couldn’t come soon enough, if nothing else to finally settle matters on the field. That evening, filled with the expected heightened emotions, pitted two starting pitchers with big-game reputations: Al Leiter and Andy Pettitte.

Both provided quality starts, but neither factored in the decision.

Instead, this four-hour and 51-minute marathon, which concluded with former Met Jose Vizcaino delivering the winning hit in the bottom of the 12th, ultimately hinged on two key moments — one a lapse in judgment and the other a lapse in precision.

With the speedy Timo Perez on first and two outs in the top of the sixth, Todd Zeile lifted a fly ball that bounded off the top of the left-field wall and came back into play. Thinking it was a home run, Perez slowed down. The hesitation was costly. Left fielder David Justice grabbed the ball and threw to Derek Jeter. Perez was heading home to try and break the scoreless tie. But Jeter’s perfect throw nailed him at the plate.

The Mets managed to break through against Pettitte, scoring three times in the seventh shortly after falling behind 2-0. Leiter left after seven with a 3-2 lead and it stayed that way into the bottom of the ninth. But the Yanks pushed across the tying run against Armando Benitez, made possible by a determined 10-pitch plate appearance from Paul O’Neill that resulted in a one-out walk. O’Neill would come around to score.

If the opener didn’t provide enough drama and this matchup itself didn’t offer enough hype, Game 2 offered a continuation of the individual saga between Mike Piazza and starter Roger Clemens.

It would be their first encounter since Clemens drilled Piazza in the helmet on July 8, concussing the catcher and prompting strong ill feelings.

What took place in the top of the first is not lost on Mets and Yankees fans alike, relived countless times over the past two decades: Piazza breaking his bat on a foul ball. The meat part of the bat ending up in Clemens’ grasp. Piazza jogging to first. Clemens flung the jagged piece of wood back in Piazza’s vicinity. Clemens’ claim that he confused the bat with the ball is about as believable as his claim that he didn’t use steroids.

Once the soap opera subsided and “The Rocket” somehow was allowed to continue on the mound, Clemens proceeded to have a typically vintage outing: eight shutout innings, two hits, no walks, and nine strikeouts.

It wasn’t until Clemens was gone when the Mets began to hit. Unfortunately, they began hitting after the Yanks had built a 6-0 cushion against Mike Hampton, Glendon Rusch, and Rick White.

Piazza began a furious, but ultimately futile comeback with a two-run homer off the left-field foul pole. Two singles and two outs later, Jay Payton connected for an opposite-field homer off Rivera. A 6-5 Yankees victory was cemented when Kurt Abbott struck out looking one batter later.

As the series shifted from the 4 Line to the 7 Line, the Mets were clearly a step behind combatants well-equipped for their autumnal ritual. Resourcefulness became woven into the Yankees’ fabric during the late 1990s.

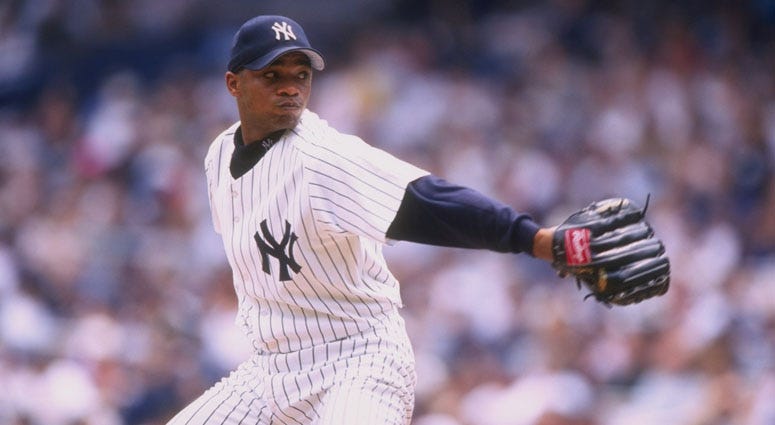

Just as sharp for this occasion was the Yanks’ starting pitcher. Orlando Hernandez put his 8-0 record in postseason competition on the line against a team that couldn’t afford to lose. Once again, the teams stayed close. And after five-and-a-half innings, the Mets were trailing 2-1.

But Todd Zeile doubled to drive home Mike Piazza for a sixth-inning tie and was in the picture again as the bottom of the eighth commenced with Hernandez on the mound — more than 120 pitches deep.

Increasing his series average to .462, Zeile singled with one out in front of Benny Agbayani. Benny may not have been a good prognosticator, but he proved to be a solid clutch hitter. He laced a liner into the left-center field gap. Todd plodded ‘round the bases – aiming to complete a successful 270-yard dash. The race was to beat the relay home. And he prevailed. The Mets tacked on another run and halted the Yankees’ streak of 14 straight Fall Classic victories with John Franco, the New York native finally in the World Series after 17 years, fittingly earning the win.

However, the Mets’ chances of building on that momentum came to a screeching halt soon after Game 4’s first pitch from Bobby Jones to Derek Jeter, who manager Joe Torre had moved into the leadoff spot. The future Hall-of-Famer and soon-to-be series MVP connected on Jones’ offering, lifting it over the wall in left-center field.

Even a two-run blast by Piazza in the third, which cut into a 3-0 Yankees advantage, did little to deter the two-time defending champs. Piazza’s homer would be the only runs produced by the Mets all night — at first against starter Denny Neagle and later against the relief efforts of David Cone, Jeff Nelson, Mike Stanton, and Rivera.

A third one-run defeat put the Mets one loss from the end. Valentine tabbed Al Leiter to help stave off elimination. And he nearly did it single-handedly.

In what was perhaps his most high-profile showcase of determination, he suffered one of his most agonizing defeats. Leiter strove to fend off the Yankee three-peat, even instigating a run-scoring play with a perfectly placed bunt. As his pitch count crept to a season-high 142 and Valentine stuck with his bulldog into the ninth, Yankee resolve began to overwhelm Leiter’s tenacity.

A walk was followed by a single. Then Luis Sojo hit a grounder that snaked its way between the reaches of Alfonzo and Abbott. Jorge Posada headed home. Jay Payton’s throw from center field bounced off Piazza. Not only did Posada score, but the carom allowed Scott Brosius to follow him in.

Piazza’s flyout to center field which ended in Bernie Williams’ mitt was further affirmation of the Yankee’s supremacy, which had also been on display throughout the series.

”There are a lot of heavy hearts in that clubhouse,” Valentine said to The New York Times, ”and I have a heavy heart with them.”

The Mets had concluded a two-year stretch that saw them average more than 95 wins and make consecutive postseason appearances for the first time in their history. In the years to follow, however, they were unable to take that final step. Thus, the 2000 World Series has since become a case of “what might have been.”

But the legacy of the 2000 Mets lives on twenty years later. It remains a successful and unique period with players, personalities, and attire, (ex: the black jerseys) which remain a vital part of the franchise’s best days.