There’s been a lot of talk these days about value. Many Mets fans wonder whether stockpiling valuable pitching assets will prove advantageous in an era when scarcity dictates that quality hitters possess the most value.

Value metrics have become the go-to statistic among many fans in this discussion as they provide a practical tool for defining a player’s contribution. But it’s hard to assign a win-value to a player completely exclusive of contextual influences such as lineup, quality of competition, difficulty of position, and even effectiveness of coaching … to assign a definitive value judgment when comparing similar players based on WAR is dubious. WAR is a broad stroke metric. On any given leader-board you can find multiple instances of players falling behind clearly less valuable counterparts. Jhonny Peralta is not more valuable than Miguel Cabrera, likewise Josh Donaldson is not more valuable than Giancarlo Stanton.

WAR is more useful in grouping players. You can, for instance, be confident that a 4 WAR player will be categorically superior to a 2 WAR player. WAR only becomes problematic when comparing players separated by smaller increments.

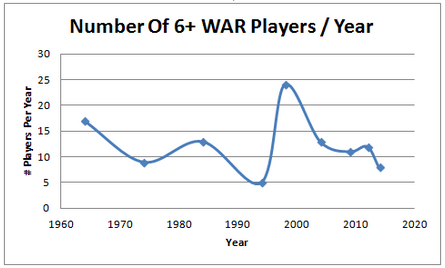

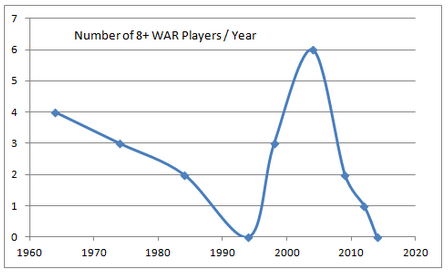

Now if we want to assign a relative value to offense in today’s game we can look at WAR over time. In the charts below you can see that there is a spike of 6+ WAR players right around 1998 (24) with a spike in 8+ WAR players occurring in 2004.

Interestingly, in 1994, at the height of the steroid era, there were only five 6+ WAR players and no 8+ WAR players. There is definitely a dip in number of high value players in recent years, but there have been other dips over the years and the correlation between the steroid era and numerous high WAR players isn’t as strong as you might think. Part of this might be whatever value is placed on a player’s defense and the possibility that steroids didn’t factor in as much on the defensive side of the game.

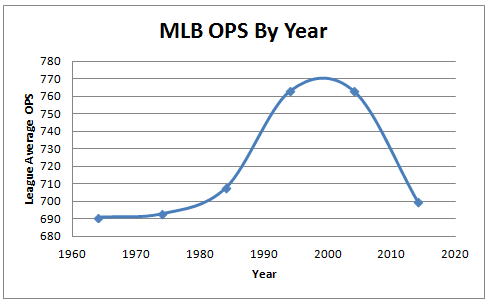

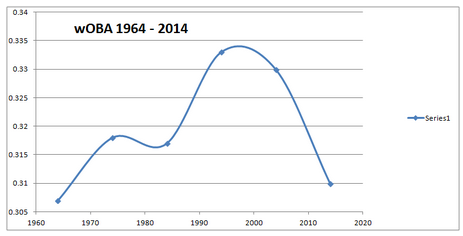

A statistic that I do like is OPS. It is the sum of a player’s on-base percentage and their slugging percentage. OPS is the only widely used statistic that incorporates all the elements of offense: patience, power, and contact. It is a relatively simple stat that gives us a good solid offensive performance indicator. OPS over time yields a much more pronounced pattern as you can see below (I also included a wOBA comparison for good measure).

As you can see, the spike at right around 1998 in both OPS and wOBA is significant and the decline from about 2002 on is steep. This correlates heavily with increases in numerous other offensive categories during the steroid era. The subsequent decline is considerable and in many ways trends all the way back to standards set back in the early 60’s.

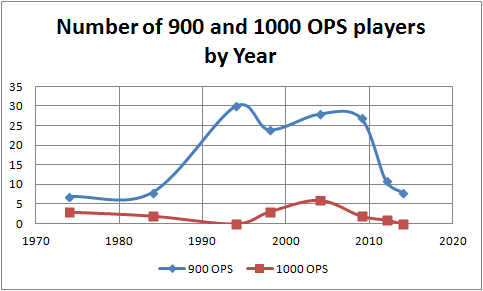

The question nevertheless remains … how does this precipitous decline in offense translate in terms of here-and-now value? Clearly there are fewer high level offensive players than there were only a few years ago … scarcity dictates that their monetary value should increase accordingly. Why have good hitters become so hard to come by? Steroids certainly had something to do with the insane number of 900 and 1000 OPS players in the late 90’s, but as the wave of PED’s subsided, like water finding its level, pitching has slowly begun to ascend to pre-steroid norms. The reason why hitters have become so scarce is because they are increasingly overmatched by pitching, which may have benefited less from steroids than hitting did.

So where do you assign greater baseball value in today’s market, hitting or pitching? 900 OPS players are fewer and further between … so from a monetary standpoint elite hitters will be expensive, probably more expensive than pitching. On the other hand, in this great contest of pitchers vs. batters, the pitchers have been absolutely destroying the batters. Good pitching is in fact beating good hitting all over the place. Tough question.

If you have the money and resources, securing an elite hitter or two will give you a rare advantage because there are so few of them available. I took the top three salaries from every team in the league and split the money between pitching and hitting and sure enough in 2014, teams spent $520,008,647 on “top 3 in salary” pitchers, while they spent a whopping $818,182,379 on “top 3” team hitting. So there is quite a difference.

If you are on a tight budget it becomes difficult to field a balanced team when you apportion a huge percentage of your payroll to 1 or 2 hitters (availability is also a major consideration), and you may be better off cultivating a pitching heavy system (since it’s clearly pitching that is carrying the day anyhow). Ideally you’d want to augment with a host of young cost-controlled home grown offensive players as well … Sound familiar?

This goes back to an earlier discussion that compared Sandy Alderson’s approach with the Mets to Theo Epstein’s strategy with the Cubs. The Mets are going to have a lot of pitching coming up in the next few seasons and the Cubs are brimming with young position players. Theo’s premise goes something like, “Since hitters are so scarce, teams will trade more than their pitching equivalent in value to obtain them.” According to Theo (and a lot of Cubs fans) because there are so few quality hitters Sandy Alderson should be willing to part with deGrom or Syndergaard and Herrera and Plawecki for a single Starlin Castro … but that’s money talking, and increasingly expensive hitters haven’t been winning on the field, cheap young pitching has.