Who needed fireworks at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium when the Mets and Braves provided a better show than any pyrotechnic display could?

What unfolded through the evening of Independence Day and continued until 3:55 a.m. on July 5 transcended franchise history and became a regular-season game unlike any other. There were a combined 29 runs, 46 hits, 37 men left on base, 43 players used, 14 pitchers, three blown saves, two rain delays, two ejections, a Keith Hernandez cycle, a formal protest, and an unfathomable homer from a relief pitcher.

“I saw things I had never seen before,” Hernandez said.

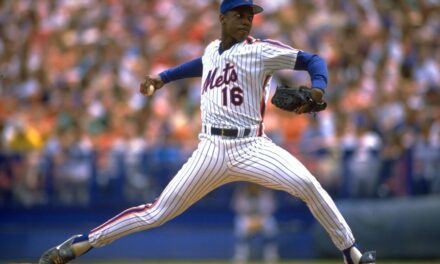

Things were wacky from start to finish — and the conditions in which they played were equally outrageous. Two hours and five minutes worth of rain delays and a bad drainage system created standing water in the outfield. Base hits hydroplaned as they skidded through the grass. The game was halted for a second time in the third inning. Davey Johnson removed starter Dwight Gooden with a reliever but was disallowed a double-switch and thus challenged the ruling.

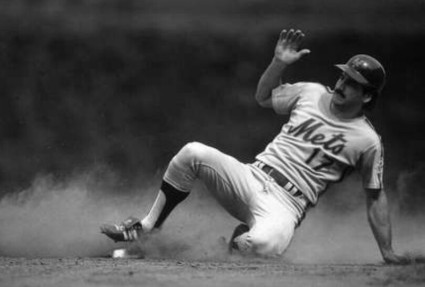

Despite being deprived of its ace, New York held a 7-4 lead in the bottom of the eighth. Jesse Orosco, nursing a sore shoulder, couldn’t shut the door, a theme that would afflict pitchers on both sides. Atlanta scored four times in its half of the eighth, including a three-run double by Dale Murphy. The Mets responded with a Lenny Dykstra RBI single off Bruce Sutter. Extra innings allowed Hernandez to complete his cycle in the 12th, but it took until the top of the 13th for New York to break the 8-8 tie, when Howard Johnson smashed a two-run homer. The Braves were one strike from defeat before Terry Harper answered. With a runner on, his drive to left field dinged the foul pole. Ten apiece.

Scoring took a break in the 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th (when Darryl Strawberry and Johnson were tossed for arguing balls and strikes). The Mets broke through in the top of the 18th by way of Dykstra’s sacrifice fly. Tom Gorman was asked to hold the one-run advantage. He retired Gerald Perry and Harper on groundouts. Up came the pitcher’s spot. But Braves manager Eddie Haas had used up his pinch-hitting options.

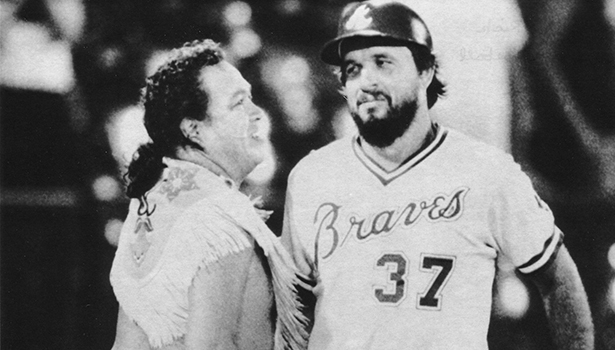

The last hope was reliever Rick Camp — and a faint one at that. Camp’s batting record was terrible, even by hitting pitchers’ standards. He toted a meager .060 average to the plate, with 83 strikeouts in 167 career at-bats. Even in this game that had already achieved “Twilight Zone” characteristics, asking Camp to stave off defeat — much less hit a home run — was a bridge too far. Or was it?

Gorman got two quick strikes. Then Camp connected. Everyone — Mets players, fans, announcers, teammates, and probably Camp himself — was exasperated when the ball went over the left-center field fence. Amazingly, it was tied at 11. But the craziness wasn’t over.

Camp assumed his normal role in the top of the 19th. What he had taken from the Mets, he gave away (and then some). Ray Knight atoned for the 11 men he left on base by doubling in Gary Carter (who caught all 305 pitches from Mets hurlers) to put New York on top. The Mets tacked on and Ron Darling came in to protect the seemingly comfortable 16-11 lead, only to watch the Braves make one more tireless charge. Harper’s two-out single drove in two and brought the tying run (and Atlanta’s newest power threat) to the plate. You guessed it, Rick Camp.

But all dramatics, like those still in attendance, had been exhausted. Camp fanned on four pitches. At five minutes to 4 a.m., after a total elapsed time of 8 hours and 15 minutes, Darling put a period on perhaps the wackiest baseball chapter ever written. This night-turned-morning would still end with a bang. Several, in fact. The stadium still proceeded with the scheduled postgame fireworks. Residents nearby reportedly made panicked calls to police — some fearing this was the onset of nuclear war with the Soviet Union.