Think about the greatest Mets trades. Keith Hernandez for Allen and Ownbey. Gary Carter for Brooks, Fitzgerald, Winningham, and Youmans. A crop of soon-to-be Marlins in exchange for Mike Piazza.

But perhaps the most impactful trade wasn’t for a player.

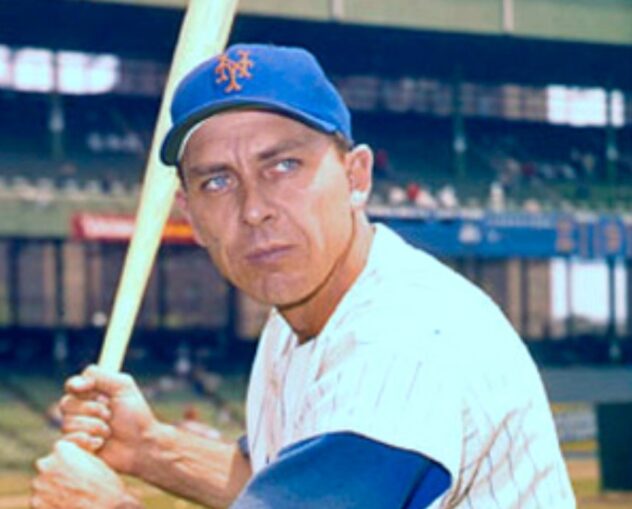

Gil Hodges had been a Met, a member of the original 1962 club in the twilight of his playing career. More famously, he was a significant part of the Dodgers’ success in the late 1940s and 1950s. The leadership qualities which made him a respected first baseman weren’t lost on organizations seeking a manager. And for more than four seasons, he oversaw an inexperienced Washington Senators club which improved incrementally each year.

Mets vice president Johnny Murphy sought a replacement for the recently-departed Wes Westrum. He had a connection in Washington: George Selkirk, the Senators’ general manager and Murphy’s former roommate when they were Yankee teammates.

Selkirk wouldn’t give in so easily. But shortly after Murphy took over GM duties from Bing Devine, the offer was Hodges for right-handed pitcher Bill Denehy and $100,000 as compensation to release Hodges from his deal with Washington. Realizing the possibility of no return if he decided to leave when the contract expired following the ‘68 season, Selkirk relented.

In the story of any franchise, there are a few seminal moments. The insertion of Hodges as manager is one of them. Inheriting a club that had suffered 100 or more defeats in five of its first six seasons, he instilled a confidence that future Mets teams would be different than their predecessors.

Hodges proved to be more patient than most disciplined leaders and less vocal, too. But there was never any doubting whose word mattered in the Mets clubhouse. Many leaders are usually feared or loved. Gil was both. No player was immune from his authority. And no player would dare question it.

As for in-game strategy, he maximized the talent at his disposal—coaxing and adjusting a lineup to create the greatest chance of victory. He allowed inexperienced players to work through tough situations and out of any rough stretches. By the end of 1968, the Mets made a significant step toward respectability, even if it didn’t appear that way in the standings.

New York improved by 12 games with a franchise-best 73 wins and a ninth-place finish—just the second time the Mets had emerged from the cellar. That was nothing compared to what took place the next year.

There were many reasons why the Mets became champions in 1969—Tom Seaver and Jerry Koosman’s brilliant pitching, stellar defense, and timely hitting. But none of that would have been possible without Hodges’s unwavering leadership. That, in short, is his Mets legacy.

Should he get a long-deserved Hall of Fame induction—better late than never—Hodges’ influence on the Mets will be a significant reason for it.