Before the Atlanta Braves became a perennial playoff team, in which the organization won 14-consecutive division championships from 1991-2005 (the lone exception coming in 1994 due to the players’ strike), the club dealt with many lean and frustrating seasons.

From 1966 (the first season the Braves moved to Atlanta) through the 1990 season, the Braves only made the postseason twice; getting swept in the NLCS in 1969 and again in 1982.

The purchase of the Braves by Ted Turner in 1976 led to the club being broadcast nationally on his superstation: TBS. Although the club finished above .500 just three times from 1976-90, the Braves raised their national profile through the cable broadcasts.

And while the team’s results were dismal during that time, one player provided fans in Atlanta and nationally something to tune in for: Number three, Dale Murphy.

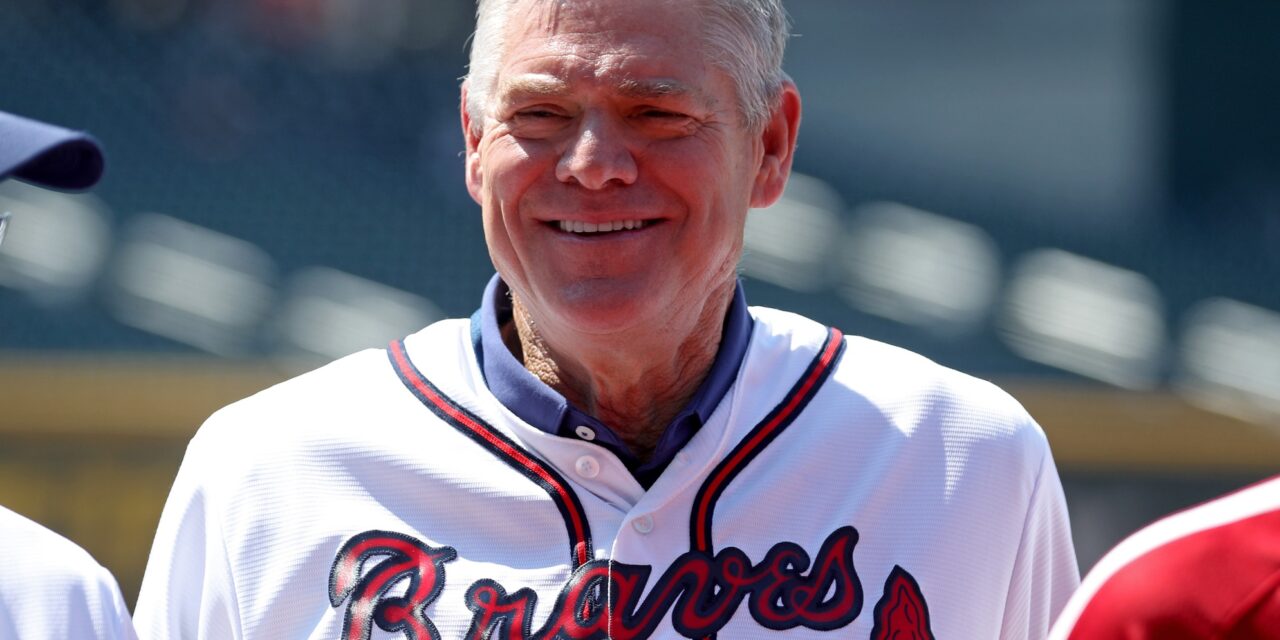

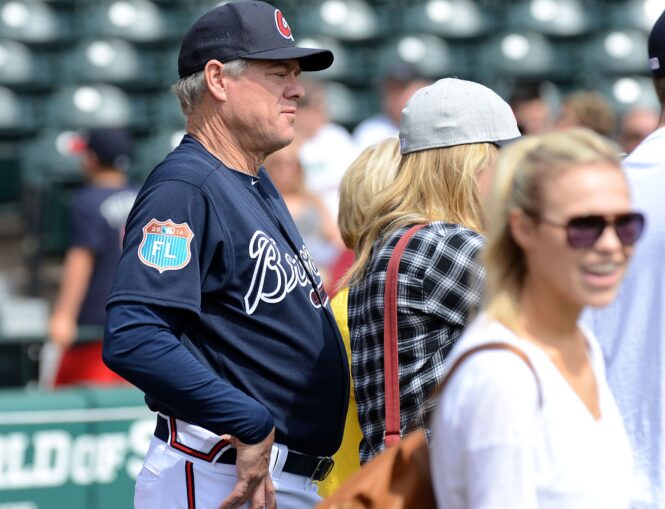

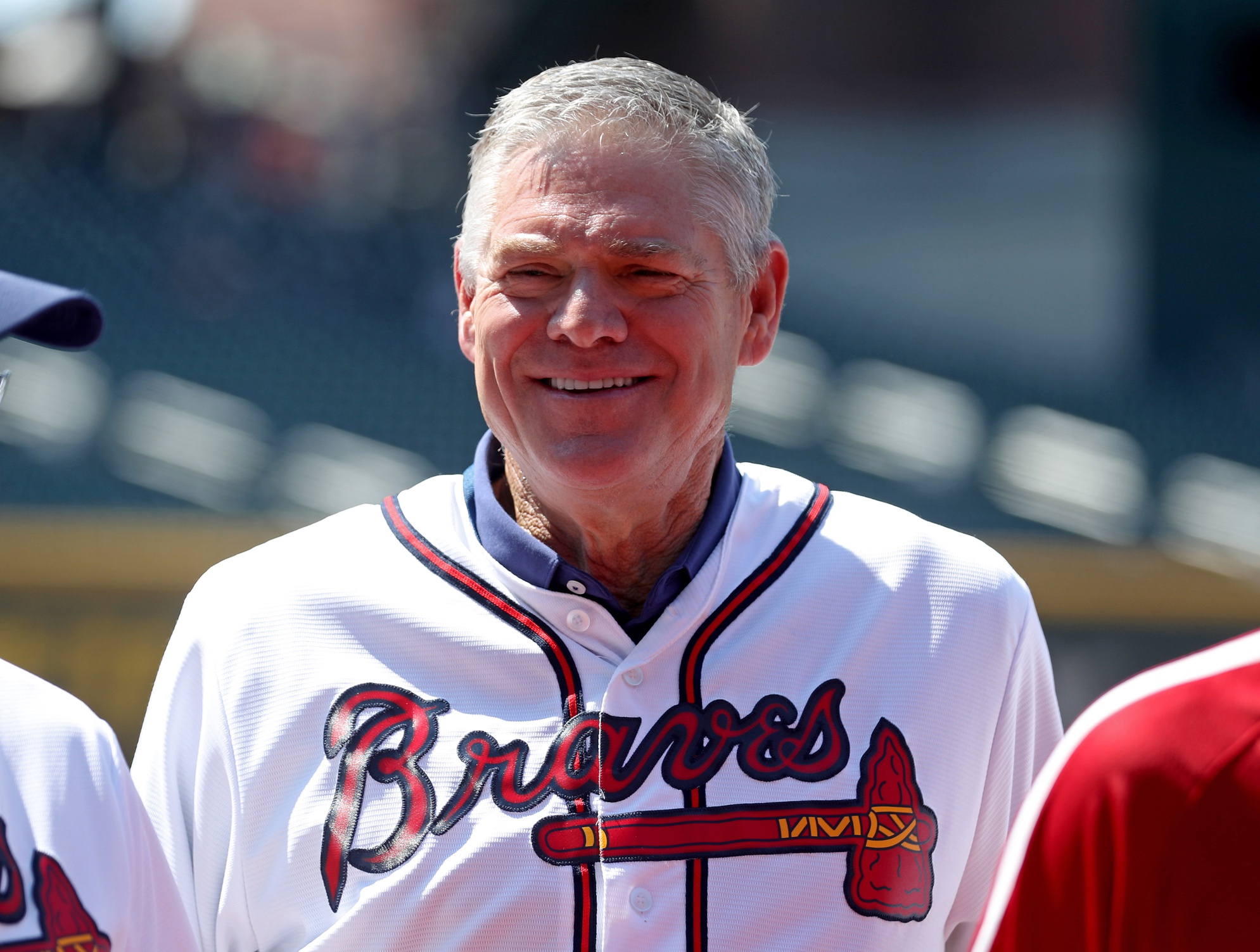

Murphy, 63, was a seven-time All-Star, two-time Most Valuable Player in back-to-back seasons from 1982-83 and a five-time Gold Glove winner during his 18-year major league career. Selected fifth overall by the Braves in the 1974 June Amateur Draft out of Woodrow Wilson High School in Portland, Oregon, Murphy’s rise to stardom took some time to develop as he was gaining more confidence in his overall game and finally found a position in centerfield after starting his career at catcher and first base.

In 1983, Murphy took home his second consecutive MVP Award, becoming just the ninth player to win back-to-back MVPs and just the fourth to do so in the National League. Of the 11 retired players to win back-to-back MVPs, only Roger Maris, Barry Bonds and Murphy are not in the Hall of Fame.

Murphy was the definition of durable, appearing in all 162 regular-season games from 1982-85. He also played in 740 consecutive games from September 26, 1981, to July 8, 1986; good for the 13th-longest streak in major league history.

The right-handed slugger was a force to be reckoned with during the 1980s. In that decade, Murphy hit the second-most home runs (308), tied with Mike Schmidt for the second-most RBIs (929) and posted the 12th-highest fWAR among position players (43.8). His 2,796 total bases was the best for the decade.

Over his 18-year major league career, Murphy hit a total of 398 home runs, drove in 1,266 runs, posted a career 121 OPS+ with a bWAR of 46.5. Murphy is one of 23 players all-time to record at least 375 homers, 1,200 RBIs and steal at least 150 bases.

Among all-time Braves, Murphy ranks fourth in games played (1,926), sixth in hits (1,901), fourth in total bases (3,394), fourth in homers (371) and fourth in RBIs (1,143). Murphy became the fifth Brave to have his number retired when the club did so in 1994.

During his fifteen years on the Hall of Fame ballot, Murphy never received more than 23.2 percent of the vote (his second year on the ballot in 2000), and only reached over 15.0 percent four times.

The former slugger was one of 10 candidates under consideration for induction as part of the 2020 Modern Baseball Era ballot. Unfortunately for Murphy, he did not receive at least 75 percent of the vote needed from the 16-member committee to be inducted into Cooperstown. He’ll get another opportunity for enshrinement in 2022.

Today, Murphy remains active in the current affairs of Major League Baseball. He’s vocal on social media, interacting with fans on Twitter who remind him daily of his prodigious achievements on the diamond. He’s also a contributing writer for The Athletic, where he brings a progressive-minded voice on subjects such as player celebrations, unfair minor league pay, and rethinking unwritten rules in the game. Murphy also lent his opinions to a podcast cohosted by Bill Riley in 2019 called Power Alley.

In 2017, the year the Braves’ new ballpark, SunTrust Park, was unveiled, Murphy and his partners opened up a restaurant just a short walk from the stadium appropriately called Murph’s. With a blend of comfort food and baseball memorabilia, Murph’s offers fans a unique baseball-themed dining experience.

Though his playing days are long in the rearview mirror, Murphy’s passion for the game hasn’t wavered. His knowledge and insight about the game are as powerful as the nearly 400 homers he hit during his impressive big league career.

I had the privilege of speaking with the two-time N.L. Most Valuable Player where we discussed changing positions, his back-to-back MVP seasons and his thoughts on his Hall of Fame candidacy.

MMO: Who were some of your favorite players growing up?

Murphy: I was born and raised in Portland, Oregon, so my earliest memory of going to a professional baseball game was the Portland Beavers, which was a Triple-A team for Cleveland.

I remember the names Chico Salmon, Luis Tiant, Sam McDowell; all guys coming through the system. Some of the guys were visiting players but my dad would take me to those baseball games.

In fifth and sixth grade I was down in the Bay Area, and then I moved back to Portland for the rest of my childhood and high school. But two of those years I lived in the Bay Area so that was in the late sixties and man, were there just some fun players to watch!

If you were around the Bay Area at that time everybody was a Willie Mays fan. And then going again with my parents to the San Francisco Giants’ games and seeing those teams: Willie McCovey, Mays, Jim Ray Hart, Juan Marichal, and Jim Davenport.

Mays was probably my first favorite player growing up. In the sixth grade, we moved over by Oakland and I actually went to some A’s games and those were really, really good teams in the start of their run which I think was in the early seventies with Sal Bando, Vida Blue and Catfish Hunter. I kind of liked both those teams but if someone asked me who my first favorite player was it’s definitely Willie.

MMO: At what point during your development did you think that you could make a career in professional baseball?

Murphy: I knew as a junior in high school going back to Portland. In high school, I was getting scouted and I knew there were scouts there. It was so different back then that you didn’t really have a lot of information, you know? I knew I was getting drafted and thought I had the chance to play some professional baseball.

In my senior year, everything was clicking and I got invited to a pre-draft workout by the Phillies. I thought the Phillies might draft me; I knew that their scout was friends and acquainted with my coach and I met him [Bill Harper]. I got invited to a tryout by the Phillies and I thought I had a shot. I think they took Lonnie Smith that same year (3rd overall in 1974).

I’m sure my coach would say, “Oh yeah, Dale, the Braves were there a lot,” but I don’t remember meeting the Braves and talking to anyone with the Braves. When draft day came the Braves called and told me I was drafted. I was like, okay, what’s going on?

I think my junior and senior years were when I was beginning to think that I might get drafted. It took me a couple of years before I felt comfortable in the minor leagues. Even though I was a first-round pick and fifth guy picked in the draft, I was still pretty naive and was pretty over-matched early in my career, until I started developing muscle and getting a little stronger.

I was pretty over-matched is what I remember, I think my early statistics pretty much confirmed that. [Laughs.]

MMO: Moving from catcher to first base to finally the outfield by 1980, what was each transition like for you? And at what point did you feel comfortable out in center?

Murphy: I was really motivated to make the change because I was catching and I wasn’t doing well enough to stay back there. I went to first base and it seems kind of obvious but sometimes you think, I can go over to first base, it’s not that difficult. But you’re involved in so much with balls that are hit to you and turn into double plays from first to second and handling throws from saving guys of errors and things like that. I played a little bit in high school but I didn’t do very well there.

When Bobby [Cox] called me in the fall after the season of ’79 he said, “Murph, get ready to come to spring training in ’80 as an outfielder.”

I was like, Okay, I’m ready!

It’s always harder to go the opposite direction from the outfield going in. If you’re going from the infield going out it slows the game down and I was very motivated because this was kind of my last chance at finding a position. Bobby and the Braves were like, let’s go for it, and Bobby put me in there really quick.

He told me I looked fine and I was starting to swing that bat and getting stronger; I hit 22 home runs in ’77 in Triple-A. Then in ’78, I hit a little over 20. My hitting was there but my defense was rough, so I was really motivated.

I wasn’t real quick but I wasn’t slow, I was kind of a big guy but I studied the hitters and I just took a lot of ground balls and got out there for BP and got a lot of ground balls and fly balls. For an outfielder, it’s good to take balls in BP because you get a more realistic flight of the ball that you might get in the game instead of taking them from a coach. But I did everything and I was ready to go and finally felt comfortable. In my mind I was like, I think I finally have a position here.

I ended up making my first All-Star team that year so things moved quickly after that.

MMO: Your back-to-back MVP years in 1982-83 were phenomenal seasons in which you hit for power, stole bases, got on base at a high clip and played terrific defense. Was there anything in particular that you worked on prior to the ’82 season or tweaked mechanically to lead to those two MVP seasons? One thing that definitely stands out for me was your big increase in walks.

Murphy: It got a little better and I got a little more experience and increased my walks, though my strikeouts were still high. The theory is, and still is, I think, in baseball, that if you’re hitting 30 home runs and driving in 100 runs those strikeouts are fine, but it’s better to mix in some walks at times.

I think it just was experience. I didn’t necessarily go into the season and say, okay, I need to increase my walks, because you’ve got to find that happy medium. You have to be aggressive as a power hitter and so you just kind of have to let it happen.

The overall thing was I felt so excited and motivated because I felt comfortable with my position not only on the field but my position with the team. It was uncomfortable when I’m not doing well at first base, I mean, I had like 20 errors [1978]! It’s like, this isn’t going to work and it’s just uncomfortable.

We were not a very good team, so they had a lot of young guys and we were trying to find ourselves. But it’s uncomfortable, do you know what I mean? It’s like, I’m not fitting in here. Then psychologically when I got into the offseason it’s like, man, I’m here, I fit in. Here’s another way of putting it: I could contribute defensively where I used to think my defense was a liability. All of a sudden I can go to the outfield and make a catch here, throw a guy out there and I was like, hey, I can contribute defensively as well.

I have to say, too, that when Joe Torre came to the Braves in ’82 he really related to me well as far as hitting. He had a great approach that I really liked and translated well to me. Bobby kind of hung in there with me and gave me a position, Joe kind of solidified some of my ideas about hitting and to not worry too much about things.

MMO: The psychological aspect of knowing that you’re helping the team on both sides of the ball must’ve been a bit of a weight lifted for you, and as you said, you felt even more comfortable thereafter.

Murphy: Yeah, it really helped me psychologically because I could be like, well, I’m 0-for-2, think out here. You could make a catch, you could save a run and you just feel like you’re contributing. That’s why when you’re a baseball player if you’re not going to get a hit then do something right in the field.

Then I started to steal a few bases and Joe gave me the green light and said, “Go ahead and steal. I’ll shut you down if it looks like you don’t know what you’re thinking about out there.”

I had the green light for about three or four years; I didn’t have to get a steal sign, I could go when it was appropriate. And with a green light, people think that means you can go and steal 80 to 100 bases. That’s why playing for a guy like Joe, he gave you some freedom and good managers are like this. A good manager lets you manage yourself and will take away privileges as you show you’re not able to manage yourself.

For instance, we’re down 5-0 in the sixth and Bob Horner is up. I steal and get thrown out, that’s a stupid time to steal. We’re down five runs, let him hit! Joe came to me and said, “Murph, you can run and you’ve got a few stolen bases. You’ve got the green light. Just go when you feel you can go.”

All of a sudden I stole 23 bases in ’82 and then I stole 30 in ’83, and then pitchers started throwing over on me.

It was a lot of fun and when you start thinking that you could help the team and help the team on the bases, help them if I hit, my confidence from where it started at in ’78-79 it just really gelled. I felt like I could help the team in a number of ways every night and that’s a fun feeling. I’m very thankful that I had some speed and it was fun to steal bases, I’ve got to admit.

It’s too bad they don’t steal as much anymore. I totally get the analytics if it doesn’t show that it’s worth the attempt, but it doesn’t mean we should stop altogether. You should be smart, figure it out and I just think that guys that can run today could steal more bases now because it’s such a rare thing that I don’t think the catchers are as ready and I don’t think the pitchers are as ready. Let’s not go 50/50, that obviously is not going to be statistically worth the effort. But let’s increase your percentage.

The other thing that instantly happens is the shortstop comes up to the pitcher and tells him that this guy will run and keep an eye on him. It distracts the pitcher and gets him to think of something else like should I slide step? Should I hold the ball as I come to my set position? Do I really want to throw a curveball here because he might be running? It’s a good distraction that I think if we eliminated totally is not the right approach. We should be stealing at a higher percentage no question about it.

MMO: What were your overall impressions of Ted Turner as an owner and what TBS did for generating fan interest and essentially making the Braves “America’s team”?

Murphy: Playing for Ted was great. If you want to compare him and George Steinbrenner we weren’t very deep as far as our teams in the early eighties. We didn’t have depth on our pitching staff and even the whole team in the minors wasn’t deep to sustain it.

But the real fact of the matter is collusion hurt us in the late eighties, it really slowed our progression down. When John Schuerholz and Bobby Cox got their positions and the organization said pitching is the key and then they were on a roll. We weren’t very deep, we couldn’t sustain it. But what Ted Turner did you could say was just so great for baseball.

MMO: Can you talk about the rumors in the late eighties involving you being traded to the Mets?

Murphy: As far as I could tell it was a true rumor. I was struggling and the team was struggling and I knew eventually something was going to happen whether I left or got traded. I heard the rumors and when I played with Lenny [Dykstra] in Philly he said, “Yeah, me and HoJo were hearing the same thing.”

It was rumored to be Dykstra and HoJo for me, those were the names that were getting thrown out there. And I was like, dang, New York!

When I first heard the rumors it was the start of me in ’89-90 telling the Braves it’s time for me to move on. In ’91 I was going to be a free agent so maybe the Braves could get a trade that someone will extend my contract and I feel comfortable about the city and the organization. That’s why in ’90 Bobby said that the Phillies would extend my contract and if you want to do it, do it. I said I’d do it because I was going to become a free agent and it was time for me to move on.

The rumors with the Mets are kind of what got me thinking because I never envisioned me leaving the Braves, but then I saw what Phil Niekro went through and it gets all messed up. It gets really sticky. That’s why there’s only a handful of guys like Chipper Jones and Derek Jeter and just a few others that stay with the same organization. It just doesn’t happen because the law of averages just doesn’t work that way. But my point is when I heard these rumors it got something in me going and I just knew it was time for me to move on.

MMO: Obviously you got to play at Shea Stadium a lot in your career and you recorded your second-highest OPS out of any ballpark you played at (.881 OPS). What are your memories from playing at Shea?

Murphy: Well, that shocks me! [Laughs.] Every once in a while Mets fans will come up to me and say, “Oh, Murph, I remember you! You used to kill us.”

And I would think, I don’t remember that. I know I did nothing against [Doc] Gooden, I didn’t like to face Ron Darling and Bobby Ojeda was tricky. During those years that was a different ballgame. That must’ve been early in my career.

I loved coming to New York, it was just an incredible experience coming to the city. Everybody knows coming to New York is different. I didn’t particularly like to hit there because of the planes, it really distracted me. If you got into the box and a guy’s getting his sign, you can hear the plane right behind you! And then you think: should I step out and let the plane go?

I remember playing against those better Mets teams in the late eighties and I’m sure I didn’t do great. I think earlier in my career helped me a bit more. And later on, I never felt comfortable hitting off John Franco. That changeup or whatever he threw to right-handers, a little screwball thing, he’d sneak one in on me.

It was fun to compete there, it’s New York! I loved going to the city and one of my favorite things was going to plays with my wife Nancy. But that kind of got me going when I heard those trade rumors to the Mets. Earlier in my career, I don’t know if New York would’ve been a fit for me. I was just a shy kid and I think you kind of go where you’re meant to go and Atlanta was a good fit for me. But later in my career, that’s why I went to Philadelphia; I decided to move on and that would get my adrenaline going for sure. I think that’s what happens in New York; the crowd sounds different. It’s different, it’s louder, you think it’s a sellout crowd but then there are only 25,000 people there! You feed off and I loved to play there.

My first connection with Rotisserie Baseball was in New York. I got up early one Sunday morning to go to church and got a cab. The cab driver dropped me off and I got out and I was walking down the sidewalk and a guy came up to me and said, “You Dale Murphy?”

I said, ‘Yeah.’

He goes, “I just traded for you.”

I’m like, ‘What do you mean?’

He goes, “Oh, Rotisserie Baseball! Keep up the great work.” [Laughs.]

I’m like, okay, thanks.

I loved playing there and I remember watching Ron Swoboda and the ’69 Mets, and now I’m out there? It was a surreal time in a kid’s life when he starts being in places that he saw as a kid and early in my career playing against guys that I was watching on TV is really weird.

MMO: In an interview I conducted with Swoboda for MetsMerized, he talked about how Shea was a hard outfield to play because the stadium stood so tall and it was hard to get a read due to the backdrop. Were there ever any issues you encountered while playing in the outfield at Shea?

Murphy: I don’t remember any. Shea was like many stadiums back then in that it was symmetrical, so there weren’t any tricky things. But I don’t remember that particular problem. Mostly it was just the noise and the crowd and trying to hear the ball off the bat so you could sense if a guy hit it well or not.

MMO: You were on the HOF ballot for 15 years before they changed the maximum to ten years. Many, including myself, believe that you should be enshrined. I’m curious what it was like for you each year when voting came around and your personal thoughts on your candidacy? *(This question was asked prior to the vote by the 16-man modern committee in which Ted Simmons and Marvin Miller were elected).*

Murphy: I was never really knocking on the door during the fifteen years, I think I hit a high in the low 20 percent range [23.2 percent in 2000]. But I still had a core of people who were keeping me on the ballot obviously, so that was a great honor in itself because that doesn’t happen all the time.

I thank the Hall of Fame that has changed it to the Eras Committee. And that was their whole point: to consider the guys from the 70s, 80s and early 90s to give us more debate. They did that and Alan Trammell and Jack Morris went in, Lee Smith and Harold Baines as well.

I’m going to get considered again this December, and I’m thankful for that because I never thought seriously that it would happen after my fifth year of retirement. If it was going to happen it was going to be a while and I knew that.

I’ve had a lot of supporters and I’m thankful that I get considered again. We’ll see what happens; you still have to get 75 percent of the sixteen voting members on that committee. There are a lot of guys that deserve to get in, I’m not like the lone ranger. There are guys like Jim Kaat who I think should be in. Bert Blyleven should’ve been in there earlier, Simmons, etc.

I’m very thankful to be considered still.

MMO: You’re very active on social media, you’re a contributing writer for The Athletic, and have a podcast called Power Alley. Can you talk a bit about your different ventures and when you decided to get active in these different outlets?

Murphy: My kids and my wife, Nancy, encouraged me to get out there. They encourage me and then I take six months to a year to make a decision. [Laughs.] But I think it all started with Twitter and seeing how cool it was. It’s a weird platform but I like Twitter.

Sometimes I’d say something and Nancy would tell me, “Maybe you need a different platform to explain.”

I tried the blog and then Nancy said I should reach out to The Athletic where you don’t have to be an every-week guy but a contributing ex-player. And they said let’s give it a whirl! Same thing with podcasting; Nancy told me to try it out.

All of these things are fun. I like to speak and give keynote speeches. These are opportunities to get your name out there and speak or make an appearance. There are some drawbacks to social media for kids and all that entails, but I try to have fun with it and give my perspective on things and I’m thankful I get to do that. I enjoy it but it’s a weird world for a sixty-plus-year-old to figure out so Nancy and my kids have helped me out a lot.

I wouldn’t have been able to play with this social media stuff. Being on TBS was one thing but having your stuff out there like that is wild. [Laughs.] But these kids can handle it.

MMO: One of the things I really respect about you is that even though you might be considered an old-school player, you have very modern ideas and thoughts about the game. Whether it’s about how emotion and celebrations are good for the game, marketing the young players more, better pay for minor leaguers, how throwing at batters who have been on a hot streak is garbage, etc. Being a player from the 80s, have you always had this type of ideology when it comes to these issues?

Murphy: Oh, no! I’m sure if you asked me in the eighties, I would have not felt the way I feel about the game now. I started in the late seventies and we still had guys playing from the sixties and that was just the way things were. Things are different now and they should be different.

Some of the things we did didn’t make a lot of sense. When you’re celebrating a home run it can be a sign of disrespect and poor sportsmanship if you direct it towards the pitcher. It was just not good to celebrate. But my point in some of the articles was we had players that did a little bit more than we remember. Pete Rose was pretty flamboyant out there, but it was his personality. People let him play and he didn’t get thrown at every time. I mean, he ran down to first, but people need to see the personalities, you don’t need to suppress the personalities. But there does come a time where it’s poor sportsmanship, but I just don’t think generally celebrations are poor sportsmanship.

In this day and age, we can’t afford to suppress the big personalities. We need the big personalities in the game. But my point is I would not be feeling these things but I have kids and I’m seeing what they like and what they watch. I think the game does have a lot of flash, excitement and good young players that we need to celebrate and market.

Again, taking this full circle, what did TBS tell us? It told us that marketing is key. And now it’s harder to expose your sport and get that exposure. It’s a crowded space. You’re going to have to market differently and do things differently. I think the NBA and NFL are a little more progressive in that regard, and baseball we’re a little slow, we’re not too progressive. But this is not the age or the era to be slow.

I don’t have a problem with trying a few new rules here and there. You have to see what works. Obviously, not all of them will. But we are a little slow and we do like the nostalgia of baseball, and we’re a little nervous about change. The thing is, a hardcore fan doesn’t want anything to change. But we’re not trying to build hardcore fans, we’re trying to build casual fans who’ll say, I think I’ll watch this.

One thing I don’t understand is there shouldn’t be any empty seats. They have their metrics down so well, they have flexible pricing. If the Phillies come in to face the Braves it’s going to cost a little bit more. So they know everything and have all of the metrics, but that upper deck should be full of kids. And I think you can fill them. If you know ahead of time that you’re going to have 10,000 upper deck seats available, imagine what you could do with them and build a fan for the future!

If you go to SunTrust Park, all you have to do is go to a game and think, wow, this is pretty cool. That kid may end up playing soccer, but he may have had a good experience at a baseball game. We’ve got to build young fans and the best way to do it is getting them to the ballpark.

MMO: The 2019 season saw a major league-best 6,776 home runs hit, and there was much talk/analysis about how the ball was different. In the rabbit ball season of 1987, homers jumped by 17 percent to set a new all-time record and then dropped almost 30 percent in 1988. You hit a career-high 44 that year: Was the ball different? And what are your thoughts about what we’re seeing in today’s game?

Murphy: Yeah, the ball was different. You hit a ball to the warning track, and you’d be like, well, that’s got a chance. Then all of a sudden in ’87 it’s like, oh dang, that ball is out of here! And then you go and look at personal highs and I’m sure there were a lot of people other than me that had career bests that year.

I don’t think you have to get into what happened except that I’ve experienced it in the past and I’m fine with it. But then you get people who look at Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa and how excited everyone was about baseball. The challenge with comparing that era to just juicing the ball right now is it was just McGwire and Sosa. Huge personalities!

I did an interview for The Athletic where I said I’m just not convinced that if we juice the ball we’re going to create all this excitement in the game and that people would flock to the stadiums like in the McGwire/Sosa years. To me, it becomes a little more commonplace and the teams that win are going to draw and the teams that don’t aren’t probably going to draw.

I think we have to concentrate on some other things. I think we need a tighter package; I think contact will come back, pitchers going a little deeper to keep the game moving a little faster, I think some of these trends will come back. I’m just not convinced that 45-50 home runs need to be the norm for people to be interested in baseball.

We need to get fans in the seats, and I don’t know if they thought this was going to be the answer or not. I think we should move the game on a little bit faster and certain things like that.

But it does look like the ball’s different and we have to come up with something that’s pretty standard so that the pitchers know what to expect and you’ve got to be fair which is the key thing.

MMO: You also have a restaurant that’s just a short walk from SunTrust Park. When did you open the restaurant and how did that idea come about for you?

Murphy: We are in our third year and when the Braves started building their new ballpark I just started thinking about it and I did approach the Braves about having something in the park. I was a little late for that but then they developed the mixed-use facility outside of the stadium called The Battery. It’s a beautiful mixed-use development with restaurants and apartments and I thought maybe something would work there.

I had two of my partners that had experience and they just kind of looked at that and said it was really expensive. We looked around the ballpark and what we did was about a ten-minute walk away [from the stadium] we got a restaurant there and we said let’s go for it.

I’ve got a bunch of my memorabilia in there, I’ve got two good partners and we serve good food. We’re in our third year now and so far so good. It’s been a lot of fun.

MMO: Thanks very much for some time today, Dale. It was great speaking with you about your career.

Murphy: Thanks very much.

Follow Dale Murphy on Twitter, @Dale Murphy3

Visit Dale Murphy’s website here.