Photo by Press Democrat

Eric Byrnes has never shied away from a challenge.

Whether it was learning to control his attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) as a youth, revitalizing his career with the Arizona Diamondbacks after being released by the Baltimore Orioles after the ’05 season, or training for and completing the Western States 100 Mile Endurance Run in under 24 hours, the competitor in him never quits.

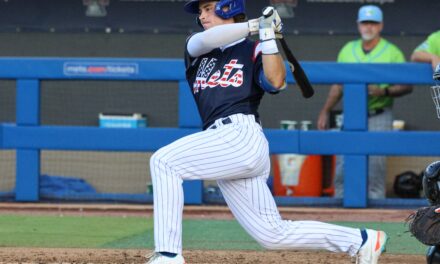

Byrnes, 42, has posted quite the résumé over not just his professional baseball career, but throughout his post-retirement life as well. The right-handed-hitting outfielder spent eleven seasons in the majors with five different organizations, posting a slash of .258/.320/.439, with 109 homers and 129 stolen bases.

His best statistical season occurred in his second year with Arizona in ’07, when the club won their division for the first time since ’02, and made it to the NLCS to battle the Colorado Rockies for the pennant. Byrnes hit 21 home runs, stole 50 bases and posted a .353 on-base percentage in a career-best 160 games played.

He’s one of only eleven different players in major league history to hit at least 20 homers and steal 50 bags in a season, joining the likes of Rickey Henderson, Barry Bonds and Joe Morgan.

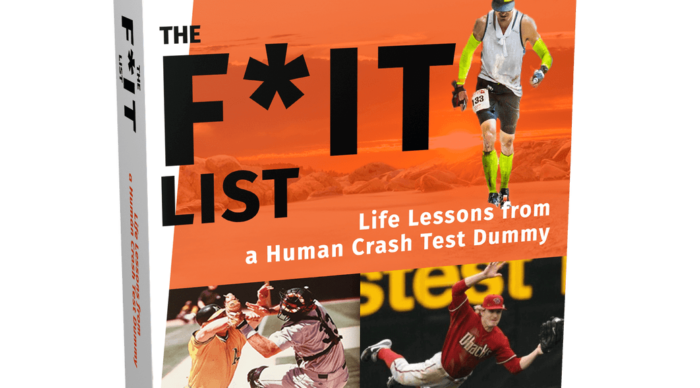

The exuberant California-native also has TV host, analyst, endurance sport athlete and author to add to his impressive career accomplishments. His debut book, The F*It List: Life Lessons from a Human Crash Test Dummy, shares life stories and events that helped shape and propel Byrnes throughout his prosperous career.

The book balances Byrnes’ own personal anecdotes with inspiring messages on how to strive for the best in oneself, and not let outside distractions damage one’s morale. Throughout the quick-read chapters, Byrnes does an exemplary job of helping to motivate, promote energy and push readers to continue to put the hard work in for whatever dream they’re vying for.

A mantra Byrnes repeatedly used in our lengthy phone conversation was, you get out what you put in. That message rings true throughout his book, as Byrnes details how important the entire process of challenging and putting in the time and effort to live one’s most authentic life truly is.

Prior to the release of his book this year, Byrnes was the subject and executive producer of the award-winning documentary, Diamond to the Rough. The feature follows Byrnes from the baseball diamond to the trails of the 2016 Western States 100 Mile Endurance Run, the oldest 100-mile trail race in the country. The goal is to finish under 24 hours, which would earn the participant the coveted silver Western States belt. Byrnes accomplished the feat, finishing in under 23 hours and describing the competition as, “Living a lifetime in a day.”

The buoyancy and diligence Byrnes has for every challenge that’s thrown his way keeps him motivated to continue to strive and attempt new feats. His affable demeanor and commitment to his various crafts highlight how putting in the time and work can lead to such a fun payoff in the end.

I had the privilege of speaking with Byrnes in mid-May, where we discussed his upbringing and how sports helped with his ADHD, the Moneyball A’s and what he’s most proud of from his career.

MMO: Who were some of your sports idols growing up as a kid?

Byrnes: I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area and I would say I had three heroes: the first one was Joe Montana, the second was Will Clark and the third was John McEnroe. I was a huge tennis player when I was a kid.

MMO: Who introduced you to the game of baseball?

Byrnes: You know what’s funny? I had a neighbor of mine that came over to my house and was the best pitcher in Little League; he was about four years older. He used to take tennis balls and fire them at me against the garage, and he really was the one who kind of taught me how to play.

My dad was a fourth-degree black belt in Kenpo Karate, and he was a sensei. He taught karate but he had never played baseball in his life, so I learned from my neighbor and it kind of grew from there. I played one year of tee-ball when I was eight, and then I got drafted into the majors when I was nine. I think I was the only nine-year-old in the league, and it was pretty tough at that point because I was competing against a lot of ten and eleven-year-olds. I was playing three innings a game and swatting flies in the outfield. When I was ten, I was playing the whole game and at third base and by the time I was eleven and twelve, I was at shortstop and I kind of developed.

My biggest thing is for any kid out there to play multiple sports, because I think it was my tennis that ultimately helped me develop as a baseball player. Seeing the velocity on a tennis serve is really good for hand-eye coordination and agility. And obviously, the same thing with karate, just being able to move and flow.

I think that’s one of the things you have to be careful about is specializing in a sport at too young of an age because there’s risk of peaking too early. I think that’s huge and the other thing is you’re not completely developing as a total all-around athlete if you just focus on one sport.

My encouragement to any kid out there is to make sure, at the very least, that you’re participating in two different sports.

MMO: In chapter eight of your book, you talk about growing up with ADHD, and how sports was a great outlet for you. How important were sports in helping you manage your ADHD, and what more do you think can be done to help kids that are dealing with ADD or ADHD get more active and involved in sports?

Byrnes: I think the biggest thing is I realized at a young age that activity is what made me feel better. They’ve now proven through brain scans that the entire frontal lobe gets fired up just with something as minimal as five to ten minutes of physical activity before they sit down in a class. We’re trying to treat this entire generation with drugs at an early age, thinking that’s the answer. And then we have nine-year-olds dependent on heavy, heavy, heavy milligrams of Adderall. I met a girl in college that was prescribed 40 milligrams of Adderall! The reason why she said was, “Oh yeah, I started taking it when I was young.”

It’s not the answer.

What people have to remember is that physical exercise does the exact same thing and yet we’re shoving these drugs down their throats. In my opinion, it’s not fair to the kids. Ninety-seven percent of physical education is out of public schools; everyday physical education. Sixty-five to seventy percent of all kids do not partake in youth after-school activity programs. I couldn’t believe that number! A lot of this is done in underserved communities and so it’s unfortunate because either they’re hanging out on the streets or spending time behind the screens and not doing anything.

If there’s one thing I’ve learned as an adult, is we, as adults, need to be active. What do you think kids need to do? You’ve got to give them something to do, and if we’re not giving these kids activities we’re depriving them. So what I’ve seen is we’ve completely deprived them of what they deserve and that’s a chance to get outside and play.

MMO: You attended UCLA and absolutely excelled. Among all-time players at UCLA, you rank first in at-bats, runs, hits, and doubles, and second in RBI. How would you describe your time at UCLA, and how it groomed you for the major leagues?

Byrnes: It was cool, man. I went in there and I wasn’t a big recruit. We had the number one recruiting class in the country, so there were like five guys basically on that freshmen class that was ahead of me.

I sat for the first four inter-squad games and I put my feet up on the bench and put my hat down over my eyes. It was kind of my silent protest. The head coach walked over and he’s like, “Hey Eric, did you see the last pitch?”

And I was like, ‘Nope, sorry I missed that one.’

He goes, “Okay, start running.”

That was the beginning of the fourth inter-squad game that we had played and I was the only guy on both teams that hadn’t gotten into play yet. I started running and I ran for three hours and didn’t stop. Afterward, he told me to see him in his office and he asked me why I wasn’t paying attention. I told him, ‘Look, I sat through three games and I got tired of watching baseball. I didn’t come here to watch baseball, I came here to play.’

He said, “I plan on red-shirting you.”

I told him, ‘If you plan on red-shirting me I don’t plan on going to school here. I came here to play baseball. If that’s the case, I’ll leave.’

He put me in the starting lineup the next day, it was another inter-squad game, and I was leading off and playing right field. And before he said, “All right, we’ll see what you can do.”

I hit the first ball off the top of the right-center field wall and then basically after that I never looked back. I started every game but one or two my entire career there, and ended up having a pretty good run.

Like anything, when you get your opportunity you have to take advantage of it.

MMO: You were drafted twice before (1994, 1997) by the Los Angeles Dodgers and Houston Astros before signing with the Oakland Athletics after they drafted you in the eighth-round in 1998. What made you forgo your professional career in ’94 and ’97 before eventually agreeing with the A’s in the ’98 MLB Draft?

Byrnes: In ’94, I was drafted out of high school, and I really didn’t know what was going on; everything kind of happened so fast. The option was sign with the Dodgers and go to Billings, Montana, or go to UCLA. At that point, I don’t think it was really much of a choice.

I remember a number in my mind of what it would take for me to sign that I considered life-changing. It’s funny, because I think back to what that number was and I think about what life is now and you have a total different perspective of money when you’re younger and also when you don’t have it.

I would recommend – unless you’re a first-round draft pick – for everybody to go to college and get that experience. Not just for baseball but for life, because I think overall, my experience at college at how to be a good roommate and teammate and how to focus the schedule [was good]. The entire F*It List came from college; the idea and concept of structuring one activity to the other which allowed me to focus and what not.

That was huge, that was a monumental time in my life. It’s funny, because all the guys participated and each day we got – it was a pissing contest of four dudes – to see who could get the most shit done in a day. That’s where I basically ripped the title of the book off of, what we were doing and what we were creating. And it has a lot of double connotation because I think part of it is an actual list of shit to get done: wake up, cold shower, weight training, art and history discussion group, civil war history class, lunch at Sandbags, one-hundred swings before practice, practice, one-hundred swings after practice, Maloney’s pint night, tutor session, etc.

That really helped me in structuring my activities and following them, but you also have to have the ability to say f*** it and that’s the second meaning. If you want to get something done, just do it. We don’t always feel like doing this stuff and sometimes we just have to move. It’s like, do I feel like taking a cold shower every day? Hell no. But guess what? I know what it does for my immune system. I know how it makes me feel, the endorphins and dopamine that it releases, you just do it.

Then there’s a third element of it where it’s basically [that] we all deal with shit in our lives and stuff that can be a tragic event. Someone telling you no, not getting into school, not getting a job, whatever it is. The bottom line is a lot of this stuff is outside of our control, and in order to move on and move forward with our lives, we have no choice but to say f*** it.

That’s kind of where the title of the book came from. The whole thing kind of really started in college, and I’m thankful for that experience.

MMO: You were a rookie in 2002, the famous Moneyball season. What are your lasting memories from that year, including winning twenty-straight games?

Byrnes: We were a group of guys that genuinely rooted for one another. We had a real college atmosphere; it was amazing to see how each and every guy had each other’s backs. You don’t see that at the big league level, you see it in college and high school but when you get to professional baseball it’s a different world.

You’ve got 25 individuals out there trying to make a living for themselves and it’s their livelihood. They’re really out there, quote on quote, fighting for their families. What’s great is that when you do things, not for yourself and you do things for other people and you really want the best for the other guys on the team, those are the best teams that I played on.

The ’02 A’s were it and I was the guy that got pinch-hit for for Scott Hatteberg, and that’s one of my proudest moments. If you go back and look at the movie at the real-life footage, you’ll see me jumping on the back of, I think Billy Koch, and just going nuts at home plate. Here I was, I just got pinch-hit for, yet I’m celebrating like I was the guy that hit the home run.

I always tell people that was probably one of my most proud moments in my big league career, just to be able to look back on that time and know that I wasn’t thinking about me. I didn’t care I got pinch-hit for, the only thing I cared about was winning the game.

MMO: What’s your view on the film and how accurate did you find the depiction?

Byrnes: There was some stuff in there that was very Hollywood, but there was some stuff that was pretty accurate. I mean, we weren’t paying for sodas out of the soda machine.

Obviously, the large reason for our success that year was the pitching of [Barry] Zito, [Tim] Hudson, and [Mark] Mulder. But also a guy by the name of Cory Lidle, who pitched for the Yankees a little bit and passed away in a plane accident in Manhattan. That was awful. Cory was lights out for us during that stretch, he was actually, I think, our best pitcher.

I think that got overlooked and the funny thing about Moneyball was it wasn’t about the pitching, but Moneyball was basically [about] trying to find value in players where other teams did not see their value. I think one big message of Moneyball is that sometimes you need to think outside the box; you need to stay ahead of the curve in thinking of how you measure the value of these guys.

MMO: In 2007 with Arizona, you stole 50 bases, slugged 21 homers and posted a .353 OBP. In major league history, you are one of just 11 players to post a season of at least 50 stolen bases and 20 home runs. What about that ’07 season did everything seem to come together for you, including playing in a career-high 160 games?

Byrnes: I said f*** it. Basically, I got traded to Colorado, sucked in Colorado. Got traded to Baltimore, sucked in Baltimore, and got released. I didn’t think I was going to have a job. I signed with Arizona for one year and thought it was just going to be one year and really it was ’06 when I said, f*** it, I’ve got nothing to lose. I think I was 30-years-old and I was looking at it like, All right, this is it.

Baseball is a real fickle game. To go out and have two shitty years in a row is the kiss of death. The way I looked at it was I had nothing to lose. I had been in Oakland my whole career and all I cared about was an opportunity to play. And having the chance to go to Arizona and get that opportunity, I was so grateful just to be able to run out there on a daily basis. I was grateful to the Diamondbacks, grateful to Bob Melvin – my manager – that gave me a chance.

I ended up hitting 26 homers, stole 25 bases, and really just revitalized my career and allowed me to go into ’07 really comfortable, man. Mathew, you go into a situation where you know the people believe in you it’s comforting and I think that was the only year in my entire career where I knew that these dudes believed in me. I was able to go out there and just play freely and not have a grander vision of just myself, too, because we had great group. Real similar to the ’02 team with the Oakland A’s, the ’07 Diamondbacks team made it to the NLCS.

It was just a great group of guys that all hung out on and off the field together and got along really well so that was cool to be a part of.

MMO: At what point during your career did you realize you wanted to be involved with broadcasting at some point?

Byrnes: About ’05 when I got released. I think my first job offer was from ESPN. I went in and did some games with ESPN Radio, and they told me they hoped I get picked up but if I didn’t they’d love to have me. I really took broadcasting seriously. In life, you get out what you put in, so I went in there and I did five games in a row for five hours a night. I was on with Freddie Coleman, John Seibel, and Doug Gottlieb. It would rotate each night, but three consummate professionals that really taught me about the game of radio.

Once I sort of went through that crash test grind I was like, Man, I want to do this. I had a passion for it, I had a passion for it not just talking about baseball but all sports. In Arizona, I actually got a TV show that kind of morphed. I did something for FOX Sports Net Arizona and then they offered to have this camera do one show a month of basically the camera following me off the field. It was really the introduction, in my opinion, to the social media craze. What social media has brought us – which is great – is behind the scenes access to what these guys do. Whether it’s an athlete, entertainer, or it can just be your best friend on a behind the scenes look of what he’s doing that day.

It was called The Eric Byrnes Show, a behind the scenes look into my life and not only my life, I always included my teammates. It was pretty revolutionary at the time and I still think it is. It’s funny, because I was just out there and I don’t think there’s been another dude that’s had his own TV show when he played.

I was grateful for that. It was pretty sweet and it also allowed me to seamlessly make the transition, I think, into broadcasting after I was done playing.

MMO: Upon your retirement, you got heavily involved with triathlons. In 2016 you completed the Western States 100 Mile Endurance Run, where you were the subject and executive producer on the award-winning documentary, Diamond to the Rough. Can you talk about when you first discovered your love for endurance running, the documentary, and the process it took?

Byrnes: Basically I got done and got challenged by three junior high school friends of mine. I mean, I had not been done playing baseball for more than a few weeks. I was playing slow-pitch beer league softball and playing a lot of golf and was surfing every day. I ran into some friends who said they were going down to do a triathlon down in Pacific Row, like the Pebble Beach area. And I said, ‘I’ll show up.’

I got my beach cruiser bike, my surfing wet suit and board shorts; I had no idea what I was getting into. I almost drowned in the water and I was getting passed by fifteen-year-old girls on the bike, it was embarrassing. I ended up finishing the run, got my ass kicked but I told each of my friends that it was one of the coolest experiences of my life. Thank you very much but that’s the last time you’re going to f****** beat me.

I went out the next day and I went all in. I knew it was something I wanted to get into. I knew I wanted to get into it almost as a kid because I used to watch the Ironman with my dad every year. I remember one of my earliest memories is Julie Moss collapsing at the finish line, I think it was 1982. That’s one of my earliest childhood memories and I was always fascinated in what would push somebody to go that hard for that long to drive themselves to the point of not being able to put one foot in front of the other.

Once I started training and I did a couple more races, I was like, Man, I really need some help in the water, and just learning how to swim and get the technique down. I ran into a triathlon coach named Frank Sole. I actually called him up, I was looking for a swim coach at Lifetime Fitness down in Arizona and I said, ‘Hey man, I need some help in the water. I’ve done a couple of triathlons.’ He said he was actually a triathlon coach too, and I’m like, Oh sweet!

Frank and I hit it off; he’s a New Yorker. I’ve always gotten along with New Yorkers because they don’t bullshit, everyone’s pretty straightforward. Frank had remembered me when I played baseball, he was either a big Mets or Yankees fan. He would ask me what I want to do with this and I told him that I want to do an Ironman. I was thinking four or five years down the road and Frank said, “I’ll have you ready to do an Ironman in eleven months in you’re willing to commit.” I’m like, You’re kidding, right? I said, ‘All right, let’s f****** do this!’

Eleven months later, I did my first Ironman. Since that point and in the process of training, my dad passed away unexpectedly just out of nowhere. It was a real transitional time in my life and it was probably the most, if not the most, emotional thing I’ve done in my life to that point, in crossing the finish line. I just felt my dad was right next to me and it really helped me cope with the loss and it allowed me to just clear my mind and have conversations with him on the long rides and training for it.

I fell in love with the sport and I’ve done eleven Ironman’s now, and slowly transitioned to the ultra marathon world in the process. The idea was to try to do this 100-mile race that I’ve been infatuated with for a while called the Western States. Once I got the endurance and I was doing Ironman, I started learning more about Western States. On my dad’s 40th birthday is when he became a fourth-degree black belt and so it was kind of like my version of the fourth-degree black belt in the endurance world was finishing the Western States 100. And ideally finishing it in under 24-hours which gets you the silver belt buckle.

I went through the process which was long, arduous and grueling, and I just trained my ass off for it. You get out what you put in and I managed it really well. My family was unbelievable and were my support team. I could not one-hundred percent have done it without them. Twenty-two hours and change later I ended up crossing the finish line.

It’s funny, people talk about living a lifetime in a day, that’s what they had described it to me as. And I’m like, That could not have been more perfect. It’s exactly what it was and you deal with the emotions of a lifetime in a day. Since then, I’ve continued to do more ultra runs and what not, and recently I did this golf thing with twelve hours of golf and somehow found my way to break the world record for most golf holes played in 12 hours which is a pretty cool feat.

But it all stems from the running and being willing to put in the miles and the time. I don’t think any of that’s possible unless you have the full support of your family and you have them on board with the adventures that the endurance world provides for you.

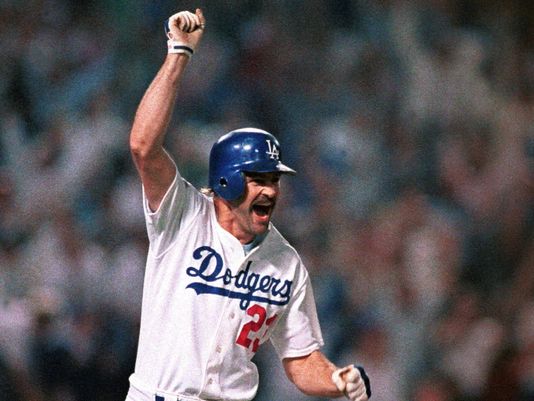

MMO: I was recently on your website, and read one of your blog entries, which is also in Chapter 60 from the F*It List. It was the story of how Kirk Gibson signed a bat for you, and inscribed the following, “I X V = R.” I recently interview Bob Tewksbury, who’s the Giants mental skills coach, who talks a lot about visualization. Can you talk a little about that interaction and what I X V=R means?

Byrnes: Image times vividness equals reality. Kirk Gibson had signed a bat for me and I had no idea was it was. It took me two days to find out but he finally let me know what it was. The more vividly you can imagine something, the more likely it is to become your reality. I really just kind of marinated on that and when I got my opportunity in baseball I just kept repeating that to myself, ‘IXV=R, IXV=R.’

I think I came in for Jermaine Dye, and I was able to get a couple of hits and really I give that phrase and Gibson a lot of credit for the success that I was able to have. Especially right then because I went on a twenty-two game hitting streak and this was right after the IXV=R. I think the model of success in any industry is consistency and that was what I was able to do is just each day I was visualizing and seeing it and being it.

Really, the transition into triathlons and then into ultra-marathons and then into breaking this world record, it’s all intertwined, man. It’s all the same shit. It’s being able to see yourself doing it and believing that it could happen.

Again, it starts with the work, but if you put the work in and you’re able to visualize and believe it can happen, and don’t be negatively swayed by outside influences I’m one of those believers that anything’s possible.

MMO: When you look back over your career, what are you most proud of?

Byrnes: It’s not what I did. Not a single home run, a single hit, a single diving catch, a single stolen base that I could point back to and say, ‘I’m proud of that.’

It’s not what I did, but it’s how I did it. And I say that in the sense that I went out there each and every single time and I laid my balls on the line, simple as that. I gave baseball everything I f****** had, dude. Everything.

I’m proud of that on and off the field.

The games are only what the fans see, [because] off the field I was obsessed. I was obsessed with being the best baseball player I could be and I’m just proud of the fact that people talk about they might mail in at at-bat or mail in a day, I didn’t do it. I can’t necessarily say I maximized my potential because I think maybe there was a more proficient way I could’ve gotten stuff done. Regardless, my production or lack of production, it was never from lack of effort.

I gave it everything I had.

MMO: Thanks for your time today, Eric. It was great to speak with you and catch up on your career.

Byrnes: My pleasure, Mathew. Thanks for reaching out.

Follow Eric on Twitter, @byrnes22

Visit Eric’s website, https://www.ericbyrnes.com/

Purchase his book, The F*It List: Life Lessons from a Human Crash Test Dummy, here.