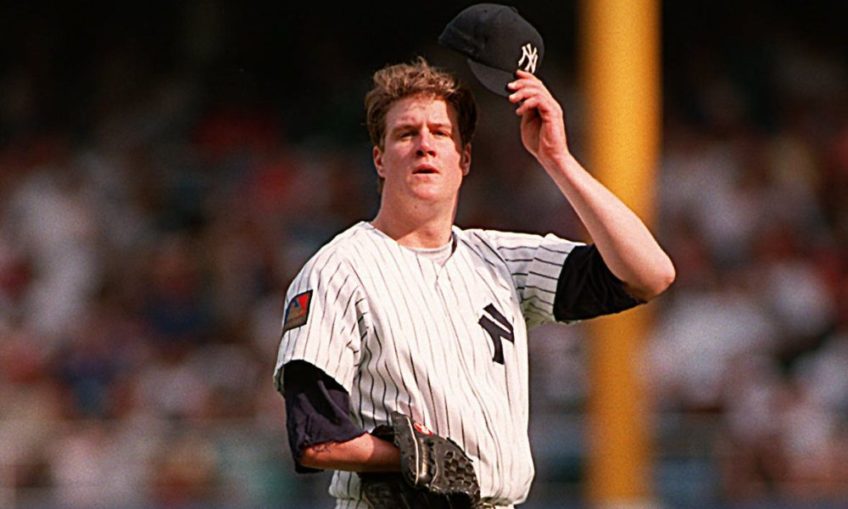

Twenty-five years ago, a left-hander toed the Yankee Stadium rubber on a Saturday afternoon in September, looking for redemption.

It was just six days prior that Jim Abbott took the mound in Cleveland on August 29, 1993, pitching against a strong Indians lineup. The Michigan native lasted just 3.2 innings that day at Cleveland Stadium, allowing seven earned runs on 10 hits with four walks and three strikeouts.

The ’93 season was an arduous one for Abbott. He was dealt to the Yankees in December 1992 by the California Angels, after spending his first four seasons thereafter the Angels made him their first-round pick (8th overall) in 1988.

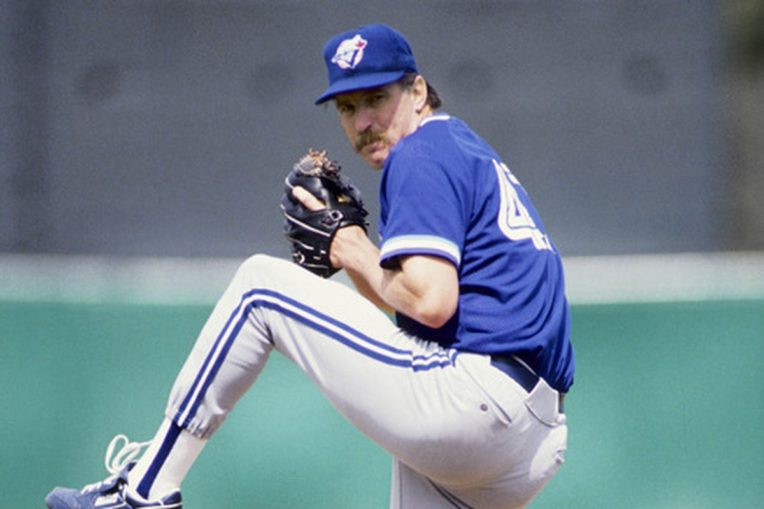

The Yankees were looking to pair Abbott with fellow off-season acquisition Jimmy Key to make for a formidable top of the rotation.

While Key was an All-Star in ’93, winning 18 games (career-high), posting a 3.00 ERA over 236.2 innings pitched and finishing fourth in the A.L Cy Young voting, the results were underwhelming for Abbott. He went 11-14 in ’93 with a 4.37 ERA and 1.6 bWAR, after posting a 2.77 ERA with a 5.7 bWAR with the Angels one year prior.

The beauty of baseball is that even in a disappointing season when players are expecting much more out of their abilities but aren’t producing it on the field, something special can occur.

On September 4, 1993, Jim Abbott tossed a no-hitter.

While that in and of itself is a spectacular feat, two additional pieces of information make it even more astonishing.

The first is that Abbott no-hit the very same Indians team that roughed him up in Cleveland and sent him to the showers in the fourth.

The second?

Abbott accomplished it without the use of a right hand.

Born without a right hand, Abbott was determined at a young age to not let his disability define or prevent him from participating in normal day-to-day activities. Surrounded by a strong support group throughout his youth, from teachers to coaches to his parents, Abbott found solace in sports, particularly football and baseball.

Abbott made a name for himself on the mound and attended the University of Michigan on a baseball scholarship. During his time, Michigan won two Big Ten Tournaments and two regular-season conference finals and reached the NCAA Tournament in each of his three seasons (1986-88).

He was the recipient of the 1987 Golden Spikes Award and became the only baseball player to win the James E. Sullivan Award, which is awarded annually to the most outstanding amateur athlete in the United States.

Abbott gained experience in pressure situations, having led the U.S. Pan American team to victory over the Cuban national team in 1987, the first time a U.S. team defeated a Cuban team on their soil in over a quarter-century. One year later Abbott tossed a complete game in Team U.S.A.’s gold medal victory over Japan in Seoul, South Korea.

His professional accomplishments on the mound are no doubt noteworthy, yet, Jim Abbott is something much, much more. His mere presence on the baseball field has given countless families of young children who were also were born with deformities and or disabilities strength and encouragement.

During his rookie season in 1989 (Abbott made the Opening Day roster without spending a day in the minors) Abbott regularly made time to talk with kids and families at the ballpark who wanted to meet their idol. These kids had someone they could relate to athletically, someone who resembled them and could inspire to be like.

For the parents and families of those kids, the interactions with Abbott offered inspiration and motivation that their children should know no limits, and to have them strive for whatever they wanted in life.

With the inspiration Abbott provided for so many during his playing career, it was fitting that he transitioned into public speaking after his final season in 1999. Abbott travels the country and shares his story and life lessons with crowds who seek to learn how he overcame obstacles and adversities and achieved greatness.

Even with his humility, Abbott realizes the difference his story makes and is proud that it helps motivate and resonate with audiences.

Overcoming obstacles and not giving in to life’s challenges made a young boy from Michigan achieve his wildest dreams. Standing on the Yankee Stadium mound that memorable day in early September, being mobbed by his teammates and receiving several curtain calls after tossing the eighth Yankees no-hitter in franchise history, Abbott was on cloud nine. All of the extra time, practice and effort he pored into perfecting his craft culminated in this moment that will forever be etched in baseball lore.

All Abbott ever wanted was to demonstrate that he didn’t need any special treatment, that he could excel even with his limitation.

What he achieved on September 4, 1993, along with the rest of his ten-year professional career proves that with the will to be great, no matter the obstacles, you control your own destiny in life.

I had the privilege of speaking with Abbott in early September where we discussed his upbringing, being a role model, and of course, his no-hitter.

MMO: Who were some of your favorite players growing up?

Abbott: I grew up in Michigan and not far from Tiger Stadium. It was about an hour away, so the Tigers were my heroes.

I followed the Tigers pretty closely through the late seventies into the eighties. Alan Trammell, Lou Whitaker, Jack Morris, Lance Parrish; all of those guys were the ones that I looked up to. Those guys personified the major league dream for me.

MMO: In your book, “Imperfect,” you talk about how growing up you wanted to be treated like everyone else, and not have your disability be a defining characteristic. You write that you were never totally comfortable or free of uncertainty, but that you had your protected place (baseball).

Can you talk about how sports – particularly baseball – helped instill confidence in you?

Abbott: Well, that’s true. I sought belonging within sports. I grew up in a sports town, a tough town in Flint, Michigan, and sports were a big deal there. We had a lot of great athletes there and that was something that called to me.

I guess sort of self-consciously I wanted to be on those teams. I wanted to fit in and I wanted to be able to play at recess and do all those things.

I tried to find a way to get in the game. I tried to find a way to play baseball and play football and do all the things that I could so I felt a little less different in other aspects of my life.

MMO: You write about the countless people you came across in your development growing up who aided you in your quest, not just in sports, but in everyday life. What did their impact mean to you?

Abbott: I was blessed. I grew up in Flint as I mentioned, and there were just so many people from coaches, parents and teachers who took time and helped me to find ways of doing things. Day-to-day things like using scissors to using a pencil sharpener to buttoning the left cuff on my shirt.

A lot of people ascribe really flowery terms to my playing baseball and sports and the truth be told, yeah, I loved to play and I worked hard at it and I wanted to be good, but I was helped along by a lot of people.

Having heard from a lot of kids across the country I know that’s the case for them and I’ve heard from other kids around the country where that’s not the case for them. I try to encourage those people who help and reach out and support in the same way that I was helped growing up.

MMO: Playing baseball required certain adjustments for you, such as learning how to switch the glove on and off after you threw. What was the toughest challenge in a baseball aspect and how long did it take for you to perfect the glove switch in particular?

Abbott: It took a long time. I remember it being cumbersome and a series of trial and error. From that very first time of switching the glove on and off, trying to find the ball, getting the glove out of the way to make the throw, and then being able to put it back on.

There were always a series of little adjustments going on, even up to the major leagues. I had to try and figure out the right glove to use. Do I use a bigger glove where my hand could slide in and out of easier? Do I use a smaller glove that might be easier to control? It was always evolving.

I was always trying to perfect it – even up to the major leagues – and worked on my fielding and on my timing of going through the motion and having that glove back on in time to field a grounder that’s back up the middle.

MMO: Talk about your experience with Team USA, including being the winning pitcher against the Cuban team (which was the first time a US team won on Cuban soil in more than a quarter-century) along with your complete-game effort against Japan for the Gold in 1988. How did those experiences help you prepare for your eventual big league career?

Abbott: That was one of the greatest team experiences I ever had, it was just absolutely amazing. Just to be invited to the Olympic tryouts down in Millington, Tennessee, it was just such a different culture.

We arrived on this Navy base where we were housed and played and we lived in barracks. Then meeting guys like Tino Martinez, Gregg Olson and Ben McDonald. It wasn’t a glamorous life. [Laughs.] Not at all. We were sleeping in barracks in very spartan conditions. It was hot and we trained, but it was just incredible, it was a great time in life.

We were all young, we were all in college. There were no professional players on that team. It was all amateur players and coaches. The travel from that, the stories and the things we went through traveling to minor league ballparks around the United States, going to Cuba, Italy, Japan, it just was incredible from a baseball standpoint. It was an incredible sense of pride to be on that team and to look around the bus with so many great players from around the country.

Then to ultimately win a gold medal, it was just one of the more exciting, incredible moments that you could ever imagine.

I signed with the Angels after that and I didn’t play any time in the minor leagues. In essence, I can’t think of a better preparation than the experiences we had playing internationally and playing for the Olympic team.

MMO: Prior to being selected eighth overall by the Angels in the ’88 Draft, did you have any notion that the Angels were looking to select you? I know in your book you wrote that there was hope your hometown Tigers would take you with the 26th pick.

Abbott: It wasn’t a complete shock. The Angels came out and expressed interest and I did a couple of interviews with their head scouts. We went through some of the same things with the Tigers.

Until the Draft, you’re so excited for it and it’s kind of like Christmas morning, you just don’t believe it until it actually happens.

The Angels did say a day or two before that they thought I was going to be the pick, but until it actually happens you just don’t know.

I didn’t know much about the Angels at the time. I lived in Michigan and we didn’t get many of the late West Coast box scores. I knew them as a team that signed a bunch of great free agents in the eighties and that Gene Autry owned the club, so it was very exotic to think of playing in California and for the Angels.

MMO: You brought up how you didn’t spend any time in the minors after you were drafted by the Angels. What was your initial reaction when you found out that you had made the Opening Day roster for the Angels in ’89?

Abbott: I was stunned, to be honest. I had every expectation of going to Midland, Texas, where everyone had speculated that I would go [to play] Double-A baseball and ride the buses. I didn’t know where I would live, who I would live with, or how I would get around, everything was so new to me.

Spring training that year was crazy. I did pretty well and there was a lot of fanfare and a lot of media attention. And because I played around the world there was a lot of international media attention so it was just a whirlwind, it was kind of crazy.

I was in Palm Springs, that’s where the Angels used to hold their spring training at the end. Marcel Lachemann, our pitching coach, pulled me aside and let me know that I was going to travel with the big league team back to Anaheim. It was just so far beyond my imagination that things would happen so fast.

I thought back to my Michigan teammates and my high school teammates and really, it wasn’t that long after, about three and a half years after high school I was in the big leagues. It was a wild time.

MMO: You detailed your rookie season in the book, but not just what happened on the field. You received so many requests to meet with parents and children who also had disabilities and you met with so many of them before games.

Can you talk about receiving that kind of attention at a young age and being a role model for so many young children?

Abbott: The feelings were very complex, to be honest with you. I had no appreciation for how many kids and families there were out there like me and like my family. I had no comprehension of the yearning to have a role model, to have somebody out there that was experiencing something that they were going through and that was so raw and so personal.

It hit pretty hard when I got the big leagues and I have a great friend with the Angels who is still there named Tim Mead. He is one of the most caring and fantastic people in the game, and that was a blessing because Tim understood better than I did at that point the importance of what was going on.

I don’t mean to overplay my importance but just the importance of those meetings and providing access, we tried to do it in a quiet way. That was one of the stipulations that it wasn’t for media consumption. That each family and kid could process these things in their own way and that’s what I’ve found over the years is that everybody deals with these things in their own different way.

There was great acceptance for it but there was also great reluctance to do it. I still wasn’t crazy about the label; I still wasn’t crazy about the one-handed pitcher in every article that was written. That was something that I fought against and battled against and yet, here it was so prominent. It was a little bit of back and forth, there were conflicting feelings about it.

Ultimately, what I landed upon was just trying to be the very best pitcher I could be. I felt like that sent a great message to kids. If they were going to have someone to look up to then I wanted them to have someone who was good, who wasn’t just participating and allowed on the team. To go out and make an impact became of my message – I don’t know if it was the right or wrong way to deal with it – but hopefully, people took something away from it.

MMO: You certainly aren’t overplaying your importance here, Jim. Your story and message hold such weight and is one that should be commended and revered for how you battled major obstacles and worked diligently at your craft. In fact, you had to work even harder considering the disability. Your words and messages mean something.

Abbott: Well thank you, Mathew. You know, to be honest, I really appreciate that and it still goes on.

I’m doing an event at Angels Stadium on Sunday (which occurred in September). My daughter started a project called the High Five Project and we’re trying to bring together limb difference kids from the Orange County area just as a little support group.

The responses we’ve gotten and the letters I get, the tweets I get. Social media is a double-edged sword, I know, but gosh there are so many great stories out there being shared, and there’s a lot more of that now than when I was growing up. It’s cool, kids believe in what they can do. There are kids out there playing hockey and basketball and MMA fighters and Shaquem Griffin playing NFL football for the Seattle Seahawks.

There’s just a world of possibilities out there and I’m just so happy to see the kids believe that and that their parents are encouraging that. It’s been a neat thing to watch over time.

MMO: Where can people find out more about your daughter’s project?

Abbott: On Twitter: @HighFiveProj.

MMO: Harvey Dorfman is someone you worked with and speak highly of in your book. What were your interactions like with Dorfman, and what did he help instill in you?

Abbott: Harvey was a legendary figure in baseball that many people may not know too much about. I was very fortunate in my career that I ran across some really interesting people who were focused on the mental side of the game.

One of them was Ken Ravizza, who worked for the Angels for a long time and unfortunately just passed away recently. His impact was profound on the mental approaches of the game and I enjoyed working with him.

Harvey was different though. Harvey was a mental coach so to speak, but Harvey wanted to delve deeper down to why you did the things you do on and off the field. My agent was Scott Boras, and Scott’s a guy that a lot of people have preconceived notions about, either right or wrong. Scott encouraged me to go see Harvey and I think he understood that maybe when I got to the big leagues I didn’t quite have everything quite sorted out. [Laughs.]

I spent a lot of time with Harvey and he recommended a lot of books for me to read. That really helped me to walk through the early years of my career and sort of processing my experiences as a child and the way I used sports, the way I viewed myself, and the way others viewed me.

It was a very profound and meaningful relationship and I really, really miss those conversations and his friendship.

MMO: Early on in your book you mentioned how part of your pre-game routine was about visualization. I spoke with Bob Tewksbury – who’s now the Giants’ mental skills coach – and he utilizes visualization, self-talk, and imagery with his players.

We know how important the mental aspect of the game is, how did you utilize these tactics before and during your starts and how did it aid you, particularly during the no-hitter?

Abbott: It was incredibly important. You know the old cliché that everyone is talented in the big leagues is true. [Laughs.] You get there and everybody’s good. You have to try and do the best you can to be the absolute best you can be every five days as a starting pitcher. I really miss that. It’s hard in post-baseball life to find a pursuit that requires that amount of dedication and that maximum effort.

I enjoyed the mental practice. The visualization, the seeing of the stadium before a start, and your surroundings: the sights, smells, seats, the umpires and competition. That real deep immersion into preparing for something long before you’re even going to do it.

I guess the idea is that if you’ve done that enough when you actually get out there the nerves and the anxiousness is all controllable and that was a really cool thing to try and figure out. In some ways it was sort of spiritual, it brings you to the moment. It brings you to letting go of the past and forgetting about what could happen and the hopefulness and just controlling what you are doing at that moment and what is influencing you.

That’s really cool that Bob Tewksbury is doing that. I always admired him and thought highly of him and I know that he’s probably making a real impact.

MMO: September 4, 1993, is forever a special day for you and baseball history. Your no-hitter against a strong Indians lineup that featured Kenny Lofton, Carlos Baerga, Albert Belle, and a young Manny Ramirez and Jim Thome was impressive – but more so because you had just faced them six days prior in Cleveland and didn’t make it out of the fourth inning.

How did you feel heading into this game? And at what point did you start realizing that you had a no-hitter going, and what are you overall memories from that day?

Abbott: It was just a magical day in hindsight. I just can’t even really comprehend how long-lasting that would be in my life and how people have identified that with my career and my time in New York, which I cherish.

It was sort of a bottoming out of my career to be honest, in Cleveland. I was traded to the Yankees with some high expectations of being a front of the rotation pitcher. That year didn’t turn out that way at all, I struggled. I was up and down and inconsistent. I had some good games and then some bad ones. I definitely felt the scrutiny of the organization, coaches, and fans. The disappointment was there, although everyone treated me very fair.

That game in Cleveland was just sort of bad, I didn’t make it out of the fourth inning and that’s always a terrible feeling. I felt like I let my team down. The next outing was almost a starting over, it was weird. It was like, okay, this hasn’t gone the way I wanted to and there’s just no way around that. This season is not going to turn out statistically to be a great season for me, let’s just go pitch.

That’s really how I felt, I was lighthearted in that game. I’m normally much more serious in my approach. There was just something about that game. It was very serious and the concentration was real but I remember goofing around with Scott Kamieniecki and Jimmy Key, so that was really different. Maybe I should’ve taken more cues from that game. [Laughs.]

And then all of a sudden it’s serious; fifth-sixth innings you start realizing and the Yankee fans are cheering a little bit louder with every out and every strike and that countdown begins.

It just ended up being a really special day.

MMO: Were there any particular plays that made you nervous that you might lose the no-hitter?

Abbott: Wade Boggs made a terrific diving play on a ball in the seventh inning, throwing it across the infield and getting Albert Belle at first base; a bang-bang play. The umpire called him out and Yankee Stadium just felt like all of a sudden there was an acknowledgment of what was going on, you know? Like, whoa, it’s still going, we still got this thing happening.

There were several plays like that but early in the game, you don’t think about it. Randy Velarde made a beautiful double play on a smash by Manny Ramirez and you don’t think of it as being robbed of a hit, it’s just an out.

Then in the ninth inning, Kenny Lofton bunted, which was crazy, and the fans went nuts on that. All of that was pretty dramatic and interesting and then [Felix] Fermin hit a long fly ball into center field that Bernie Williams chased down. Then the groundball to Velarde from Baerga hitting left-handed against me because he didn’t like the cutter in on him as a right-handed hitter.

It just was a dramatic sort of game and then the whirlwind of excitement afterward with curtain calls and sharing that with Matt Nokes and sharing that with my wife that night in New York City.

You wake up in the morning, go to the ballpark, and your life changes in some small way.

MMO: Did you shake Nokes off at all that day?

Abbott: No, I remember us being pretty lined up.

I really liked pitching to Matt, he was an enthusiastic guy. He would give you a fist pump after a good pitch and when you would strike someone out he would spring up and fire the ball down to third base and he really gave you a great target and worked with you. You didn’t feel like his offensive output that day bled into how he went about his duties behind the plate.

I always liked throwing to Matt. I was excited he was behind the plate that day and his enthusiasm played an enormous part of how that game went and I loved sharing it with him.

MMO: You now work as a motivational speaker. Can you talk about that and how you first got started with motivational speaking? Who are some of the groups and people you speak to? What messages do you hope to get across to your audiences?

Abbott: I’m not sure I’m crazy about the term ‘motivational speaking.’ I guess I am and I try to be at the end of the day.

What’s really cool about my life and my career is that if you look at the back of that baseball card you’ll see some really awesome moments; some great years and things I’m really proud of. There’s also some struggle and disappointment and that’s very real.

I think being able to step back and think about it and being able to share those experiences with people from a professional standpoint, I think people relate to that in terms of their own careers and how years go and how a career stacks up. Obviously from missing my right hand and being able to share the creativity and optimism that’s involved in finding a different way and ultimately coming to terms with all of that.

All of that adds up to being able to try to tell people a story that honestly, I’m pretty proud of. I think there are inspirational aspects to it, not just in my own efforts but in others and the people that I encounter and the people who helped. It’s been so gratifying and it’s very rewarding.

It’s not as good as winning a major league game, I will admit that. [Laughs.] But there is something really satisfying to it.

MMO: When did you initially start your public speaking and do you travel across the country?

Abbott: I do, I travel all across the country and I’ve been doing it now for about ten years. It’s kind of sneaked up on me but I started very slow.

People ask me: how do you get started in speaking? I just went and spoke to different places. I found myself in some crazy, crazy towns and crazy places speaking to crazy groups, it wasn’t at all a lucrative pursuit for a while. But I’m really proud of it. I guess I’m almost as proud of it as my big league career because it’s something that I’ve been able to craft out on my own, you know?

I’ve thought of the things I wanted to say. I write what I say, I base a lot of it off the feedback I’ve gotten from incredible groups around the country through the years. There is a real strong sense of pride when you get in a car or get on an airplane and come home after speaking to 400 people and it worked, it connected. I’m very lucky.

MMO: When you look back on your career what are you most proud of?

Abbott: I’m most proud of representing where I came from. I’m most proud of representing my parents, of trying to represent my hometown, of trying to represent the University of Michigan.

I remember how much uncertainty was involved back then, I remember that. I try to put myself in my parent’s shoes when they had me, with the uncertainty they faced and the fear that must’ve been in their minds.

So I’m proud of that.

I’m proud that this story makes them proud and that it went much better than they hoped. I’m not sure if I’m saying that correctly but I’m proud of that and I’m proud of my family and proud of my daughters now.

The fact that my career sends a message of possibility is a direct reflection of the influences that I had in my life.

MMO: I can’t thank you enough for your time today, Jim. Your story is so influential and motivating, it was truly an honor to speak with you.

Abbott: I appreciate it, Mathew. Thank you for reaching out and I look forward to connecting down the road.

Follow Jim Abbott on Twitter, @jabbottum31

Visit Jim’s website, https://www.jimabbott.net/