The 1986 New York Mets team is one that will forever be revered by fans.

Lauded for their gritty style of play, the ’86 club was one in which no matter what the score or situation, the team never felt like it was going to lose.

It’s hard to argue with that statement, considering the club won 108 regular-season games, running away with the East Division by 21.5 games.

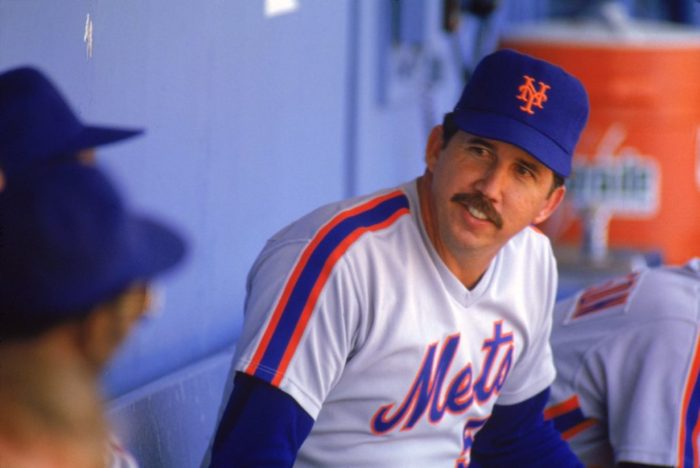

On the first day of full-squad spring training in ’86, one man knew this club was going to be special.

Manager Davey Johnson, who was entering his third season as manager of the Mets, told his squad that not only were they going to win the World Series that year, they were going to dominate baseball.

After finishing second in the Division in ’84 and ’85, winning at least 90 games in both years, Johnson had a strong intuition that his club was ready to take the majors by storm.

Johnson, 75, recollects that ’86 season as if it happened just yesterday. His vivid memories and the way in which he speaks about his players comes across like a proud parent sharing their children’s accolades.

The camaraderie, hustle and sheer talent that his club had was something special, but what made the group really gel, according to Johnson, was how each player bought into their specific roles on the team.

“When everybody has a role, then it’s a team effort. When there are individuals who don’t know their role and are being wishy-washy, that creates a lot of problems,” Johnson said.

Most fans remember Johnson from his seven years managing the Mets from 1984 to 1990, compiling a 595-417 record, the most wins by any Mets manager in franchise history. They’d be remiss to omit his thirteen years spent as a three-time Gold Glove-winning second baseman, playing the majority of his career with the Baltimore Orioles under Hall of Fame manager Earl Weaver.

It was in Baltimore that Johnson discovered his passion for sabermetrics, going so far as to program an IBM 360 mainframe to project the optimal batting orders for Weaver’s Orioles.

Johnson was an early pioneer of sabermetrics, using his degree in mathematics to better understand and develop ideas of how to best utilize lineups and match-ups.

Over his thirteen-year playing career spent in parts with Baltimore, Atlanta, Philadelphia and Chicago, Johnson posted a career 110 OPS+, amassing 1,252 hits and 136 home runs. His ’73 season with Atlanta was a high mark for the right-handed hitter, as he posted career highs in home runs (43), RBIs (99) and hits (151).

His 43 home runs established a new record for a primary second baseman, eclipsing Roger Hornsby’s 1922 mark of 42.

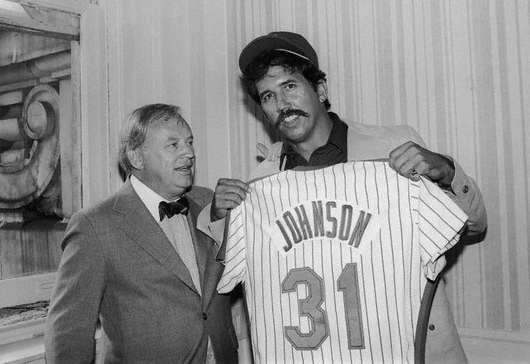

Playing in four World Series and winning two with the Orioles (1966, 1970), to witnessing both Hank Aaron and Sadaharu Oh breaking Babe Ruth‘s home run mark, to leading the Mets to their second World Series Championship in club history, Johnson chronicles his fifty-plus years in baseball in his new memoir Davey Johnson: My Wild Ride in Baseball and Beyond, co-authored with Erik Sherman.

The baseball lifer recounts his early years as a child of an army officer, his playing career, five managerial stops, and the behind-the-scenes anecdotes from his tenure in New York.

Upon his final season managing in the majors with the Washington Nationals in 2013, Johnson retired with a win/loss record of 1372-1071, and his .562 winning percentage is 12th all-time among managers with at least ten years of service. The two-time Manager of the Year (1997, 2012) is also one of just three managers in major league history to lead four franchises to the postseason, along with Dusty Baker and Billy Martin.

Johnson’s memoir relives his storied baseball career and offers tremendous insight into one of the greatest seasons in New York sports history.

I had the privilege of speaking with Johnson in early May, where we discussed how the book took shape, his playing career and his memories from the ’86 Championship season in Queens.

MMO: What prompted you to write the book and what was the process like for you?

Johnson: My wife was on a buying trip in New York, and we met with Erik Sherman (co-author). My step-son, Jeremy Allen, said that I should meet with him because he’s been writing a lot of books about the Mets.

I said, ‘Sure, I’ll be glad to meet with him.’

I really had no interest in writing another book because the one I wrote with [Peter] Golenbock was supposed to be a diary of the season, and became a mishmash.

I met with him and I really liked him, and my wife encouraged me to do something with him. The more I got talking [with him], I really liked Erik Sherman.

One thing led to another and it was difficult when I did the first book because Golenbock made me talk into a recording device after every game. That was a pain in the neck. And then he asked me questions once every two weeks or so. It was supposed to be a diary of the ’85 season, and he actually did it one year too soon, but that was such a pain in the neck.

When I talked to Sherman he said, “Look, I’ll have a lot of prepared questions about each year of your life. I can meet with you whenever you feel like you need to. I can also just talk to you on the phone.”

And I said, ‘That’s great. I’m 75-years-old and I don’t want to be traveling a whole lot to do this.’

And that’s what we did.

MMO: One of the things you mention early on in your book is how you admired the way Earl Weaver got to know his players, and that’s something you took into your own managerial style. Was that something you found to be an important aspect of your managing?

Johnson: I think that’s overblown today. I think they hire guys who get close to their players.

I think the most important thing – and I try to point out in the book – was the team gets along when everybody has a role, and that everybody agrees with the role they’re put in. Everybody knows that if they have a lesser role if they’re good at it, they can move up in their role. When everybody has a role, then it’s a team effort. When there are individuals who don’t know their role and are being wishy-washy, that creates a lot of problems.

The toughest thing about managing – and I said it in the book – is that you have to handle a pitching staff and the bench. The way you handle it and the way you protect your pitchers is not expecting too much from your starters and not letting them – when they’re late in the ballgame – lose the game so that they at least have a positive outing. All of those things are very important to the harmony on the club.

I get sick and tired of hearing about how he’s a great guy. He’s only going to be a great guy if he handles the pitching staff and the bench well, that’s the most important thing. As a whole, everybody knows who should be playing and who shouldn’t. The manager has to know that and more, and that’s the biggest thing.

MMO: You were known to be very analytically-inclined as a manager, and many might not know that you were also that way as a player with Baltimore. You write about your fascination and use of sabermetrics in the book. Can you talk about where you first developed your interest in analytics? What is your take on the sabermetrics used in today’s game?

Johnson: To answer your first question: I was a math major. I was going to be a home builder and a bunch of other things. After I had about 120 credits I had to go to my dean and ask, ‘What am I closest to?’

And he said, “You’re closest to a degree in math. You can’t get a degree in general contracting because you can’t take plumbing and electricity during the baseball season, so you’ve got no chance there.”

So I went ahead and got my math degree.

There was a guy that wrote Percentage Baseball, his name was Earnshaw Cook. When I was in Baltimore, as a player, I was very interested in statistics and I had dinner with him. I asked him out and I had read his book but he went overboard. He used statistics totally analytical and with nothing to do with the personalities and feelings of the players.

He was the first guy that ever used on-base percentage and how to set the table, and you should use guys that know how to get on base in the one and two [spots], and your third hole hitter’s usually going to be the highest on-base guy. Then the guys that had the extra-base hits that were run-producing will be down the line.

I thought it was fascinating and so I used [it], and this was way before anybody even had a small computer like a telephone, an IBM 360. I programmed it with eight different lineups and used the statistics we had before in a variable number generator to create the same kind of year with guys hitting in different orders. I was trying to prove to Earl [Weaver] that I was better off in the lineup hitting second. [Laughs.]

I did all my data and played one hundred games. It took the computer about ten minutes with eight different lineups, more for me putting the punch cards in there. Then, when I gave the huge printout to Earl, he threw it in the garbage can and said, “Get the hell out of here!”

I know he looked at it, he would look at a guy and he’d go 3-for-4 and then he’d look at his data from the past week and if the guy went 3-for-4 he might play the next day. But if he felt like he was a streak hitter – like [Don] Baylor went 3-for-4 one day and wasn’t playing the next day – and he was a streak hitter. I said, ‘Earl, you’re all messed up.’

You asked me about sabermetrics today. When you program a computer there’s such a thing as garbage in, garbage out. Now what they’re doing now is a lot of garbage in and a lot of garbage out. Like launch angles and velocity off the bat, all of those things are garbage, they mean zilch. Guys are trying to change their swing to hit more fly balls, it’s all garbage.

I’ve talked to and played with some of the greatest hitters of all time: Frank Robinson, Hank Aaron, Ted Williams was a buddy of mine, I managed against him. The one thing about hitting is the closer you can get to a straight line to the ball, the shorter your swing will be. If you start trying to take a longer route there to get elevation on it you’re going to have to commit too early. You’re not going to make solid contact and you’re going to be beat a lot of the time, or you’re going to be guessing wrong.

All of the best hitters were zone hitters, and they looked to get their bat in the hitting area as quickly as possible. Once they got into the hitting area, hit down and through the ball, then they had a little elevation to their swing. But hitting down and through the ball is the only way to hit. I don’t care what these gurus now [say]. Most of them haven’t played a lick of baseball and they’re doing all this research. I think it’s crap in, crap out.

MMO: You spent eight years with the Baltimore Orioles as a player (1965-72), went to four World Series with the club and won two. When you look back at your tenure in Baltimore, what are some of your fondest memories?

Johnson: We took a lot of pride in our defense and when I joined the club, I was with two phenomenal fielders in [Luis] Aparicio – who was my roommate and shortstop – and Brooks Robinson. Boog Powell had good hands but he just stood on the line and ate sunflower seeds, so I had a lot of ground to cover.

The other thing – and I didn’t mention it in my book – if infielders had been taught the footwork at second base, they wouldn’t have had a problem. Like the [Chase] Utley rule, where you’ve got to go straight in, that’s a Little League or high school rule. The big-league rule was as long as you can touch the base you can go in or out and I was taught by [Bill] Mazeroski and [Bobby] Richardson on how to do the footwork.

The problem with today’s deal is nobody learns the footwork at second base. They think second base is an easy position to play because you’re short to first; all you have to do is catch a ground ball and flip it to first. The key to being a good second baseman is the footwork and knowing how to do the footwork and not be taken out.

One guy hurt me but I still turned the double play. He leaped through the air and came down on my left foot and I got a broken toe and fifteen stitches. I told him if he didn’t learn to slide the next time he came down there I wasn’t going to turn the double play, I was going to hit him between the eyes. When I came back in about three weeks, we were playing Detroit again, and he was running down there and he went way into the outfield grass.

They don’t know the footwork and the footwork is getting across the bag and not putting much weight on your left foot. You kind of pirouette like you’re letting a bull run by. They don’t teach that anymore so everybody gets hurt down at second base and now it’s Little League style; they have to drive straight in and you can do anything you want down there.

MMO: Your 1973 season was the finest of your career, as you posted career bests in games played (157), hits (151), HR (43), RBIs (99) and bWAR (4.4). Your 43 home runs set a single-season record for a primary second baseman. In the book, you write about how you altered your approach at the plate and were finally healthy. Were those the two main reasons for your breakout season?

Johnson: I started trying to be like my old self [like I was] in the minor leagues. If the ball was down and in, I hit it over the left-field wall. Down and away, just hit it to right-center. I hit the ball where it was pitched.

When I got to Triple-A, Darrell Johnson [manager], who kind of hit like Brooks Robinson only a lot worse, had an inside-out swing. He wanted me to work on inside-outing the ball to right field more often. Watching Brooksie, Brooks could take an inside pitch and hit it to right field. There were a lot of jokes about me trying to work on it, but I worked hard.

In ’71, I went back to hitting the ball where it was pitched. If I hadn’t run over two catchers and separated my left shoulder I had 16 home runs by the All-Star break. I only ended up with 18 that year. Then in ’72, I had a terrible year because I had a subluxed shoulder. Weaver kept sending me to the hospital and nobody diagnosed it until I was traded to the Atlanta Braves. They diagnosed it as a subluxed shoulder from running over catchers and it stretched all the muscles in my left shoulder. I couldn’t pull through with my left hand, it would collapse.

The Braves’ doctors said I had to push out against my car door for ten seconds and then do it many, many times over and never lift weights above my head. I did that and I knew I was back, I knew I could hit the ball hard.

I had that bet with Darrell Evans, I had two home runs in April and he had nine. He had 20 RBIs and I had 9. I said, ‘Just give me seven home runs and 11 RBIs and the best two out of three at the end of the year on home runs, RBI, and average [wins].’

I blew him away, and he never paid up. [Laughs.]

MMO: While playing for Atlanta, you got to be teammates with Hank Aaron. By the 1975 season, you were playing in Japan for the Yomiuri Giants, and were teammates with Sadaharu Oh. Can you talk a little bit about getting to play with two of the most legendary home run hitters in baseball history?

Johnson: Both had great strokes. Sadaharu Oh had a great, short stroke to the ball, as did Henry Aaron. Henry hit off of his front foot, but that barrel would get to the ball out front and he’d hit the ball.

Early in his career, he would just hit it where it was pitched. Later in his career, he pulled everything. He knew what pitchers were going to throw him and he could take a low and away slider and hit it over the left-field wall. He was short and quick to the ball and he could hit off his front foot.

Sadaharu had the big leg kick but was really quick to the ball, and he hit the ball where it was pitched, too. Tremendous power, he was the Babe Ruth of Japan. He started as a pitcher, like Babe, and then he became a first baseman. I was hitting, not right behind him, but I was on deck when both of them broke Ruth’s record.

MMO: When did you realize you wanted to manage, and what were some of the things you picked up from your former managers over the years?

Johnson: You learn from all of your managers. Earl Weaver was a very interesting guy and I learned a lot from Earl. I thought he was too tough on young kids because he would yell at them from the bench, “Swing the bat” or whatever. A lot of times, he would be in the tunnel smoking saying, “I can’t look at this pitcher pitching. I can’t look.”

He was really good at handling the bullpen. You pick up things from the way guys manage.

Hank Bauer was a gruff old guy and he didn’t have much clue on how to use a bullpen, but he was pretty good offensively as a manager. All the managers you play for you always pick up something good from each.

When you go to manage, I always tell everybody, it’s really important to manage in the Minor Leagues because you see how you evaluate talent and how you use them and if you’re correct in your evaluations. If the players agree with you, you know you’re doing a hell of a job. But if they disagree with you, you may have some questions to answer.

It was easy for me because I had managed two or three years in the minor leagues and even put together a team in the Inter-American League. When the Mets came to ask me if I would manage the big league club, I was totally ready.

MMO: On the first day of full-squad Spring Training in 1986, you held a team meeting where you told your players that you weren’t just going to win the World Series that year but dominate baseball. What made you so confident that your club was ready to take the baseball world by storm that year?

Johnson: Well, first of all, I had them in ’84, and we won 90 games that year. Half my team was not as strong as it should’ve been, I couldn’t close a lot of games with half my pen. I had certain guys in the lineup that were out and then in ’85 we corrected a few of them when we got [Tim] Teufel to kind of help out [Wally] Backman, because Teufel could hit left-handers and Backman couldn’t. Same thing with HoJo; we got Ray Knight.

We filled all of the holes that we had in the lineup and so I knew that my bullpen was strong. We had guys in my bullpen that liked both sides. Nobody could bring somebody in that could keep us from scoring runs because I had the right moves to make.

We could’ve won it in ’85 but [Ron] Darling hurt himself toward the end of the season, so the Cardinals won. We won 98 games, but we had all the problems solved going into next year so I told them, ‘We’re not going to win, we’re going to dominate.’ I think Whitey Herzog – even by the end of April – said, “Nobody’s catching the Mets.”

And we dominated, we won 108 games.

MMO: Two players that you had the chance to watch blossom into stars in this town were Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden. You saw them both as young prospects and as All-Stars. Can you talk about what you saw in both of them early on in their careers?

Johnson: Darryl from early on was a guy that needed a father image in his life, and he didn’t have one. I tried to be it. I wasn’t there for him all the time, he left me in Triple-A when I was managing there very quickly.

Dwight Gooden, who I saw when I was in Kingsport, was 17-years-old and I managed the club for about a month. I had Randy Myers, Floyd Youmans and Gooden. Floyd Youmans was throwing a side, he was all over the place, but had great stuff. Randy Myers same way.

Seventeen-year-old Dwight Gooden came in there and he was hitting the low and outside corner with about a 95-mph fastball and threw it on the inside corner and he’s throwing his curveball over the plate. I go, ‘Holy moly! Doc, how do you hold your fastball?’

And he said, “Four-seamer when I want giddy up on it, and (inaudible) seams when I want a little lateral movement.”

He had great command and I said, ‘That’ll work, kid.’

The thing that I was really upset about was he was having a great year in Kingsport, but they weren’t a very good club, and our farm director moved him to Northern New York to the A-ball team that was going to win. I said, ‘Wrong move.’ I told them he’s going to go up there and try to impress his new teammates and he shouldn’t. He did and he hurt his shoulder a little bit from overthrowing, I was so hacked-off at them about that.

The next year they said something in a meeting that Lynchburg may be too high for him. I said, ‘He’s ready for the big leagues.’

Sam Perlozzo was managing Lynchburg and I told him he’d be fine. And he was fine there. I think he was 19-2 or something, and I call him up to Triple-A and he won two or three games for me.

I knew he was ready for the big leagues but [Frank] Cashen said, “Oh, he’s too young. He’s only 19, we can’t bring him to the big leagues.”

I said, ‘Keep your mind open in spring training.’

He did and, of course, made the club.

MMO: You bring up in the book how the organization was trying to change some of Gooden’s mechanics in ’86, and how it had adverse effects on his performance that year. You even state that the drop off from being dominant to very good might’ve even caused Gooden to start using drugs. Can you elaborate on that?

Johnson: Frank Cashen felt that if he didn’t have all the action with his arm – I don’t know where he got all of this information – I know it didn’t come from [Mel] Stottlemyre. If he didn’t have all of this arm and leg kick and whatever it would be more healthy for his arm. You don’t mess with success, I don’t care if they ran on him or whatever, I never was worried about that because they couldn’t score.

I think that messed with his head. Any time you try changing somebody, that was my complaint. It’s like having a young Strawberry and starting to work with him on his hitting, or Henry Aaron or some great talent. You just don’t do that, you don’t ever tell them that they’re doing something wrong. The only thing you tell them is that what you’re doing positive and they know that and if they work on that more it overshadows all of their shortcomings.

We didn’t do that with him and I think that’s one of the problems. For me, the indecision on his part was that something was wrong with him. He couldn’t have been a better guy. He was at the ballpark the earliest, he never looked like he was staying out late or drinking; he loved the game.

They also didn’t want him to switch-hit because they were afraid of him hitting left-handed that he would hurt his shoulder and hit him. I said, ‘Nobody’s going to hit Doc. He can throw it 100-mph and he knows where it’s going!’ Anybody that would hit him would be crazy! But they took that away from him and that upset me, too.

Darryl was an unbelievable talent and I was tough on him a lot of the times when he would come late, and I would fine him. He would donate it to an orphanage in New York. He’s doing great things in life now and I’m so proud of him, so that’s good. I hope and I keep praying for Dwight to be the kind of man I always knew he could be.

MMO: Every Mets fan can likely recite Game Six of the ’86 World Series, but one storyline many might not know is the personal revenge you got against Red Sox manager John McNamara. Can you talk about the past history you had with McNamara, and what made that Game Six victory even sweeter?

Johnson: A lot of people didn’t know it but [John] McNamara was catching when I was tearing up the Eastern League, and Earl Weaver was my manager. I was tearing the cover off the ball and he was behind calling pitches.

He called for a couple of curveballs on me, I’ll never forget it. I bailed a little bit, it was kind of hard because it was Binghamton and the sun was setting in left-center. It was kind of hard to pick up the ball because curveballs didn’t bother me. I said, ‘If he throws me one up there again I’m not moving.’

He called for an up-and-in fastball and hit me right in the mouth and bounced out forward and chipped a bunch of teeth and broke my nose. I heard people yelling, “Run, run!” It hit me in the mouth!

I went to the hospital and they had to fix my nose. I never forgot McNamara called that inside fastball on me. When we were one pitch away from losing the World Series to him, I was praying, Please let me get even. Let me get even.

We made a comeback from two runs down and one out away with nobody on, to the wild pitch for the tying run, and then Mookie hitting the ball by Buckner to win the game.

Then I knew it was over. I said, ‘It doesn’t matter now, momentum is on our side. I know everything’s going our way.’ We were behind in the Seventh Game three runs, [but] I knew we were going to win it. And we won it easy.

MMO: In the book, you detail how after the ’86 season Cashen and the front office started dismantling the championship club. The one big trade that you were very opposed to was the eight-player deal that sent Kevin Mitchell to San Diego. You write that you were very interested in the Mets going out and signing future Hall of Famer, Andre Dawson. Do you feel like if the front office had left the team as it was, or, went out and signed a guy like Dawson, that the Mets would’ve built a dynasty?

Johnson: We would’ve. Frank had this weird thought that when I was manager, that he would never sign a free agent. And I thought, You’re not using all the tools available to you, Frank. I mean, this guy (Dawson) you can get for $500,000, it’s a steal! We could use the pop in his bat and I hated to lose [Kevin] Mitchell, that was the biggest blow to me.

When we traded [Lenny] Dykstra and [Roger] McDowell, I don’t know what management and ownership were telling them, but Nelson Doubleday was the best owner I played for. Fred Wilpon came in and got half the club and he was a little harder, to say the least.

Things happen, you know? I thought I was going to be in the Met organization for a very long time.

MMO: I spoke to Howard Johnson in a previous interview for Mets Merized, and he told me that what made that ’86 team so special to him was the way in which you dealt with all of the personalities on the team, and made them feel like they all had their specific roles. That goes back to what you were saying earlier about keeping peace in the clubhouse when guys know their roles.

Johnson: Probably the toughest decision I had was the Mookie/Dykstra deal. Mookie was a beloved player and he had a lot of talent. He had a few holes but he was just a great player and person on the club. I had to kind of use him and Dykstra in a joint role. It was easier after [George] Foster left. Before we traded Dykstra, I said to Cashen, ‘When he plays every day he’s going to hit about .220. He’s going to get used to hitting left-handers, but he’s still going to be on the base about thirty-three percent of the time. But the next year he’s going to be great.’

And he said, “I can’t wait and groom a guy for a year.”

He traded him to the Phillies and he hit .220 and the next year he was hitting over .300 and on-base forty percent of the time. Those things kind of stick with you and kind of hurt, because here was a guy that I didn’t get the most out of for my team. So that hurt me as much that I wasn’t there for Dykstra.

MMO: Fast forward to 2011-13, where you managed the Washington Nationals. You once again got to manage two of the game’s brightest young stars in Bryce Harper and Stephen Strasburg. Did you see any similarities between Strawberry/Gooden and Harper/Strasburg?

Johnson: Totally two different personalities. Strasburg [was] very held within, kind of quiet. Both great talents but different personalities. Both of them were driven to be great and, of course, I had Harper when I think he was 15 in a home run hitting contest. I was in St. Pete when he hit the 420-foot homer and won the award, I gave him an award when he was fifteen. I put his name in the hopper when I was working part-time for the Nationals.

Managing both was easy. The thing with Harp was I told him just have fun, just go do your thing. He’s a special talent. I didn’t think he needed to make any changes hitting or defensively or whatever. Neither did I think the same with Strasburg, he had great command. I had him in Cuba for the Olympic qualifier, he’s a great pitcher.

MMO: You were one of ten candidates up for the Today’s Game Era Committee ballot for the Hall of Fame back in 2016. I’m curious, what your thoughts are on your candidacy for the Hall of Fame? Do you think about that kind of stuff much?

Johnson: I really don’t. I’m fortunate enough that I’m in some States’ Hall of Fames, and I think that’s a great honor. Maryland, Texas, New York, I think there’s one other.

Awards never were very important to me. The satisfaction I’d get is if I felt I did a good job. And as a player it was, did the team win? Four World Series as a player and I was in Japan in a World Series.

The main thing for me as a manager was I always wanted to make sure that all my players played up to their potential. I didn’t want to be the guy that ever held them back from reaching their potential. If in my estimation I did that, and if I didn’t abuse anybody so they got hurt under me from throwing too much or too often, I was very pleased with myself. That’s all I really cared about.

MMO: When you look back at your overall career, both as a player and manager, what are you most proud of?

Johnson: Just that I always had one thing in mind: what could I do to help make this team win? Aparicio taught me to take a bunch of ground balls because you can be a better fielder, and I won some Gold Gloves because there’s pride in it. My arm got better because I played more catch. It’s the same thing that goes into managing. All you want to do is what you can do to help the team have the greatest chance to win?

It’s how you use players and how everybody has a role. How you need to be consistent with that role and how you’re not to be abusive in that role. It doesn’t matter how important the game, I could never have done what [Tommy] Lasorda did – and it was a great move he did – in the ’88 playoffs when he used [Orel] Hershiser what seemed like every day. I couldn’t do that to myself. Of course, he knew Hershisher a lot better than I did, that he had a rubber arm and he could do that and it wouldn’t hurt his career. I always felt that with pitchers the most they could do was every other day. And that was for relievers, with starters if they threw a whole bunch of pitches they needed at least three days off.

Times are changing now. I see more managers abusing pitchers, young guys pitching every day or two days in a row that were starters. I see this happen all the time. It’s the new way to use everybody I guess, it’s just going to hurt them in the long haul.

MMO: You’re seeing more and more reliance on the pen, with teams carrying a lot more relievers with the starting staff not going as deep into games anymore.

Johnson: I learned this under Weaver and it’s very important: you have a long right and a long left. If the starter doesn’t get there you use one or the other for whichever match-up is better or whichever one’s most rested. This is when you only had ten pitchers, okay, but you still had guys in roles that were important. Now, instead of five in the bullpen or six in the pen if you had four starters, now you have eight.

You still need guys that are long guys that you rest and don’t use but every two days off and then can pitch again. Then use the short guys every other day. They don’t use them that way anymore, now it’s just mix and match and I worry about them in the long haul.

MMO: You were a manager that excelled at utilizing your pen and bench, knowing the opportune times to bring guys in and have their best chance at success.

Johnson: That’s the way you play the game. I had clubs who said, “Should we make the clubhouse smaller? Because everyone seems to be going off in their own direction.”

I said, ‘The only way to make it smaller is for everybody to know their role. And if everybody knows their role and are happy with it, and know if they do better they’re expanded, it’ll be a happy clubhouse.’

That’s the way it was everywhere I went. It’s not so much being friends with them, it’s relaying to them the truth about what their roles are and having them prove you wrong and that they’re better than that.

MMO: Thanks very much for your time today, Davey. It was great to look back on your career. I wish you all the best with the book!

Johnson: You got it, buddy. Take care.

Follow Davey Johnson on Twitter, @TheDaveyJohnson

You can purchase Davey’s book, Davey Johnson: My Wild Ride in Baseball and Beyond, here.