Lastings Milledge knows all about growing up with lofty expectations.

Selected 12th overall in the 2003 MLB June Amateur Draft by the New York Mets out of Bradenton, Florida, Milledge was listed as the best 16-year-old in the country by Baseball America, and later ranked as the best five-tool high school talent by the publication.

In 2006, and at just 21-years-old, Milledge was thrust into major league life as Xavier Nady hit the disabled list. He collected his first major league hit (a double) in his third at-bat on May 30 against Miguel Batista and the Arizona Diamondbacks. The talented young outfielder played in 56 games with the N.L. East Champion Mets in ’06, splitting time in both corner outfield spots.

With all the fanfare that comes with being a No. 1 pick by a team, so too, comes the criticism.

His first major league home run — a solo blast in the 10th with no one on and two outs — tied the game up at six against the San Francisco Giants at Shea. Upon returning to right field for the top of the 11th, an elated Milledge high-fived fans in the front row while jogging to his position.

The rookie was met with contempt by the media, with manager Willie Randolph telling the Florida-native to tone some of his actions down.

While Milledge endured some difficult and contentious moments throughout his career, which included a taped note above his locker at the end of the ’06 season which read, “Know Your Place, Rook,” Milledge counters that it afforded him to the opportunity to learn and grow from his mistakes.

Seven years removed from playing his final game in the Major Leagues with the Chicago White Sox, Milledge, 33, has taken all the lessons he’s learned from his six years in the big leagues (plus four seasons in Japan and one in the Independent Leagues) to help nurture and assist the next generation of players.

Specifically, Milledge is on a noble quest: to afford opportunities for minority and less-fortunate kids to learn and play the game of baseball.

Along with his childhood friend and business partner, Logan Wells, Milledge has opened up two baseball academies near his hometown in Florida. The idea came about when the pair, along with Wells’ fiancee Ashley and Milledge’s wife DePree, were stationed in Milledge’s home during Hurricane Irma. While browsing the Internet, they came across a young man’s social media account which featured several of his own baseball videos. Milledge and Wells were intrigued by the young teen’s swing, with Milledge comparing it to Andrew McCutchen‘s.

The pair got in contact with Kameron Wells, the African-American teen featured in the online videos. Milledge took Wells under his wing, intrigued by the prospect of helping the young player reach his full potential. He invited Wells to a showcase at Perfect Game, a youth baseball business that promotes amateur events, and one in which Milledge was an early pioneer of in his young teens. From there, Wells demonstrated the strongest arm in the showcase and now attends Miami Dade College.

The experience with Wells and seeing his success sparked the idea for Milledge and Logan Wells to open up facilities in their local community.

The pair officially opened up their first facility, 1st Round Training, in Palmetto, Florida, in December 2017. They train and mentor kids as young as 2-years-old (yes, 2-years-old!) and recently opened up a second facility in Milledge’s hometown of Bradenton called Manatee Innercity Baseball.

Milledge is well aware of the various programs like RBI (Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities) which is designed to promote the game to kids in disadvantaged areas. However, Milledge has a different blueprint, one in which entails a more hands-on approach to bringing the game to African-American children.

“We have got to get in there and really train the kids if we want to make an impact,” Milledge said. “I say we as ex-black American ballplayers, we as the MLB Union and we as Major League Baseball owners and players. If we really want to do something then this is how it’s got to be done, and no other way.”

He opines that in order to promote the game and encourage minority kids to play baseball over the more popular and less expensive sports like basketball and football, there needs to be further involvement from communities, ex-black Major Leaguers, and a willingness to donate time to not only teach baseball but about life.

“The common goal was not to get to the big leagues, but to make you better as a person and set your bar higher than just getting a college degree or high school diploma. Setting the bar super high and that’s what it’s all about right there,” Milledge said.

Milledge has also spent off-seasons attending youth basketball and football games, speaking to parents and asking them about their children’s possible participation in baseball. The former major league veteran is doing his own due diligence in seeking answers and motives from these parents and hopes to continue to drum up interest for the game that gave him so much.

His passion and sincerity for helping a new generation of kids are immediately evident when speaking to Milledge. He implores others who have been afforded similar opportunities in the game to take notice of the blueprint he’s set up and continue to provide an outlet for the African-American community.

Being a kid that grew up in the inner-city and received help in pursuing his own dreams, Milledge comes full circle now as someone that can assist in a young kid’s life and dreams.

I had the privilege of speaking with Milledge in late May, where we discussed his baseball facilities in Florida, what his ultimate goals are, and the controversial high five-game.

MMO: Talk to me about how you started 1st Round Training in Palmetto, Florida. When did you start it and what did you hope to accomplish with opening the facility?

Milledge: It started roughly around the time of Hurricane Irma. One of my dear friends, who I grew up playing baseball with, and his parent’s helped me out. They all came over to my place. I stayed more inland and they’re right on the water, so they were in the flood zone. His brother, Rick Wells, is the sheriff of the county and he ordered everyone in that flood zone to evacuate. Instead of driving 15 hours to Georgia, where the storm ended up hitting anyway, they came inland 20 minutes to my house.

We kind of just boarded up and we were looking on the Internet and messing around looking at different guys’ swings, watching a little bit of football; just trying to enjoy it as long as we could before the power would go out.

We came across a young man’s swing who Logan [Wells] showed me. From there, I told him I really wanted to get in contact with the kid because I think he had something special and he reminded me a lot of Andrew McCutchen back in the day, minus the speed.

I got hold of him and he was very flattered that I wanted to help him. He knew who I was and he was ready to get to work. I told him, ‘I’ll make it happen. We just have to both put our heads together because we’re 690 miles away from each other.’

We made it work. I talked to his parents and we started to immediately get to work. Long story short, he was a JV guy last year and not so confident. I got with him and showed him a couple of things. He always had the talent, I didn’t teach him the talent level. But it’s the confidence and how we work at the pinnacle of the sport, how we work in the big leagues vs. how you work in high school or collegiality. I just showed him how we do it, how I did it, how guys that I played with that are Hall of Famers did it.

I showed him how to work and this year he ended up hitting .400 with five home runs. I went to one of his games and I saw his first home run and from there I was like, I just want to start doing this more for the black community.

You know and I know what it is, there’s no need to even get into it, it’s national news every year. I was like, I just have to start doing this for more minority kids and black Americans to bring them into the game. Everybody says, “Yeah yeah, RBI [program], and we need to do this, and need to do that.” They donate a couple of balls and a couple of gloves, but that’s not going to do anything. We have got to get in there and really train the kids if we want to make an impact. I say we as ex-black American ballplayers, we as the MLB Union, and we as Major League Baseball owners and players. If we really want to do something then this is how it’s got to be done, and no other way.

We have to get hands-on and not just throw a couple hundred thousand dollars or a million dollars around and divvy it up between the whole nation and think we’re going to make waves. We’ve got to get hands-on and get these kids trained up and put them in the best position possible to get a college scholarship. That’s what it’s all about.

MMO: In the latest Major League Baseball Racial and Gender Report Card, the numbers show that just 7.7 percent of players on major league Opening Day rosters were African-American, which matches the lowest percentage since MLB began tracking the numbers in 1991. You mention being more hands-on in training and development. Along those lines, what else do you feel needs to be done to get more African-American youths participating in baseball?

Milledge: The thing about it is the participation is there, let’s not get it confused. The interest is there, it’s just not possible for these kids to play. It’s not possible because rec ball is at an all-time low now. Nobody wants to go to the Little League World Series anymore and nobody cares about the Little League World Series anymore. People are more into Cal Ripken [Baseball] and travel ball being the leading organizations in youth sports now.

I think that the interest is there, it’s the money that’s dividing everything. I would say baseball is more expensive than golf now with the travel ball and everything like that. It’s $1,000 a weekend to go travel regardless, even if you’re going thirty miles away from home. I can go 30 miles away from home to St. Pete beach, and for me to hang out and have a nice weekend, it’s going to be $700-800. There are no more $50 rooms anymore, everything’s $120-140.

Nowadays, it’s a business with travel ball. Guys are making a living on travel ball and I’m not faulting those guys because they’re donating their time. You can’t do anything for free, per se, if you weren’t fortunate enough to play Major League Baseball for ten to twelve years and make millions of dollars.

I get it, they’re donating their time and wanting to get compensated. That’s just how the world is. You put in the work and get paid. You can’t fault those guys, but at the end of the day, it’s the kid in the urban areas that are suffering and they’re forced to play basketball or football because rec ball or for football Pop Warner and all of that stuff is huge.

Now you’ve got the seven-on-seven leagues and the flag leagues so these kids are playing year-round. It’s safer because they’re playing flag for half of the year, and then they’re playing contact for three months out of the year. They’re getting better without putting the stress on their bodies with playing 20 or 30 games.

Now, these kids are getting more reps without playing three months and waiting nine months to be competitive again. Basketball and football were already drawing interest from the urban kids, but now it’s even drawing a bigger interest. Not only is it cheap, but you can play it damn near eight months out of the year.

The thing about how do we do something, I don’t mean to toot my own horn, but you’ve got to do the blueprint that I’ve been doing. You have to create the nonprofits and have the people in the community get behind you. I can want it all day for the kids, but if the community doesn’t want to get behind it, there’s nothing else I can do. My hands are tied.

It’s almost like Lastings Milledge the person, Lastings Milledge the baseball player, Lastings Milledge the ex-major leaguer; he’s here and he has a facility, let’s just keep it going.

Honestly, that’s the only way. It’s the only way. I’m sorry to say it but when you’ve made $10-12 million, who wants to be bothered with a whole bunch of kids all day? Not everybody has my passion and you can’t fault them for that because they’ve dedicated their whole lives to the game and they just want to be done with it.

They may want to enjoy life and play golf and enjoy their parents while they’re getting older. I get it. This is what it’s going to take, it’s going to take ex-major leaguers, guys who the kids can YouTube, guys who they can see and touch the success of. My kids come to my house, they see the success.

They see the Maserati I’m driving; they also see the ’98 beat-up truck I’m driving, too. But they can see the success and that’s very, very essential. They can see that this guy worked hard and he had success. Having success isn’t always about being a pro, or getting to the big leagues. It can be saving $100,000 on a D1 scholarship. Or even a D2, it’s money anyway.

I do think a little bit differently than other people. At the end of the day, it’s for the common goal of bringing the kids to baseball. To train them the right way so they know the right information and, ultimately, keeping kids out of debt and getting their school paid for free while playing the game, that’s all.

MMO: I read that you also opened up another facility called Manatee Innercity Baseball in Bradenton. Is that a similar facility to 1st Round Training?

Milledge: Yes, it’s similar. Obviously, I have more white Americans, people in the 25-30 percent tax bracket that’s able to come and pay $60 for 45 minutes. They have the money and they also want the information. I don’t do it by myself, I have Logan, whose parents helped me out and believed in me because they knew my passion at an early age.

I was being groomed at nine-ten years old on how to carry yourself in the corporate world. If you’ve got a million dollars, what would you do with it? I knew that by the time I was thirteen. I’m not tooting my own horn but you could’ve given me a million dollars at thirteen and I would’ve done the same exact thing that I did with it today: pay my parents’ house off and pay their credit cards off for me putting them in debt by going to USA Baseball and traveling all over the world and country.

All of this stuff is what Manatee Innercity Baseball is exposing these kids to. Not only learning this game and bringing them to the game, but also teaching them how to be successful. Not a million dollars, not $100,000, it could be $40,000 it could be $30,000 a year. Knowing what to do with it and learning how to be a good humanitarian is what Manatee Innercity Baseball is all about.

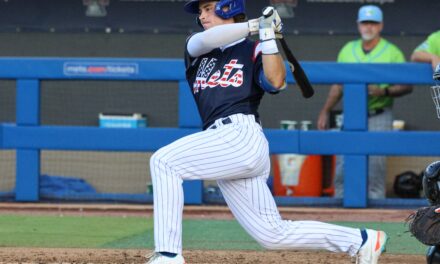

Lastings Milledge, Photo from 1st Round Training’s Instagram

MMO: And when did that open up?

Milledge: It opened up roughly five and a half weeks ago. But we’ve been doing non-profit work ever since the day we started. Ever since the day that I reached out to Kam Wells and we started doing that, that’s really when the non-profit work really started.

We didn’t know what name or what outcome it was going to be; all we knew was if anybody wants it, they can get it. They can get the information, they can get the blueprint and everything like that. The non-profit work started about eight months ago, but officially, about five and a half-six weeks ago.

MMO: I also read in the “Where Are They Now” Baseball America piece, that you spend the off-season attending youth football and basketball games to talk to African-American parents about their children trying baseball. What gave you the idea to go about doing something like that? Have you seen further interest and involvement from those you have spoken to?

Milledge: Yes, and the reason why I started going to the games and why I started interacting with the parents is because – I’m sorry to say it – but you as a reporter you don’t know. You can’t go to every African-American mother and ask them why their kids aren’t playing baseball because you may not be diverse and that’s not a thing that’s against you. People are used to what they’re used to. That’s not a knock on them, that’s just not what they’re around. With that being said, a lot of the media doesn’t know the true, true answer. They can only speculate.

I started going and asking and bringing in a couple of kids off the street, like literally off the street and bringing them in and saying, ‘Look, come to my cage tomorrow at five.’ They’re going to say yes because they see my Maserati. Okay, that’s fine, I got you in.

I wanted to get the true facts. I don’t want to speculate, I want to ask. Every time it’s, “Well, I can’t travel. I work three jobs and I just can’t afford it.” I can’t afford it and I don’t have time to get my kid to practice because with football everybody carpools and stays in the same neighborhoods. Baseball is not like that. [With] baseball, you can be separated by fifteen miles.

Johnny is not going to pick up Lastings if Lastings stays 15 miles outside the city in a rough area. That’s the ugly side of it. If you’re making a million dollars you’re not coming to the hood, that’s just [being] honest.

You know how I am, I shoot it straight. I’ve been shooting it straight since I was 19, which is probably why that got me into a lot of trouble. [Laughs.] Now [that] I’m away from the game, I can really give the answers of what people are looking for, what people are really speculating on. I can give them the true answers.

This is what an inner-city parent is thinking about, these are what my parents were thinking about and yes, I was in the inner city but my parents made good money, decent money. Not enough money to be traveling all over the country. I needed help and it was a team that helped me.

I want to be able to give the kids what I received from parents that believed in me that wasn’t so diverse. It was new for them to be around a different culture, so they learned with me.

I had to learn how to conduct myself around corporate people at nine and ten years old. I had to learn as well and everybody learned and came together for one common goal. The common goal was not to get to the big leagues but to make you better as a person and set your bar higher than just getting a college degree or high school diploma. Setting the bar super high and that’s what it’s all about right there.

MMO: What drew you to baseball over football and basketball growing up?

Milledge: It was a family business for me. My dad got drafted, my middle brother got drafted, and my oldest brother got drafted. They all had raw talent but they could never put it on display.

My parents couldn’t afford to send two of my brothers to $450 camps. That was just the luck of their draw where they were only separated by two and a half years. Everything that had to be invested at that time was double. When camp cost $400, it was $800. When it cost $250, it cost $500. That was a little bit of luck for me because I was the only kid separated by nine years, so that played a kind of big role where my parents could invest a lot in me because I was the only kid left in the household.

MMO: Do you have any further plans to open more baseball facilities? Do you envision branching it out outside of Florida?

Milledge: We want to start in our area first. I already have Kam on board to where if you foresee something four or five years down the road, well, every kid that I help I want them to start what I’m doing for them in their respective communities. That’s how we grow. Not just Lastings Milledge and Logan Wells growing this thing globally, it’s going to take the kids who have been taught to have the domino effect.

When we’re all dead and gone, hopefully we have so many facilities around for the urban community.

MMO: As a baseball instructor at the amateur level, do you have any interest in potentially returning to the professional side one day as a coach or manager?

Milledge: Probably not. I like the amateur world. In Major League Baseball, you’ve got to put your time in. You’ve got to start all over in the minor leagues again, where I feel like that I should be higher. Maybe not in the big leagues but somewhere around Double-A or Triple-A, because that’s where the kids need the most mentoring.

It’s not all about coaching; these kids are not going to get any better because they have the talent that they’re going to go to the big leagues with. What’s going to separate those guys is the mentorship. How to handle yourself off the field, and how to handle yourself when you’re getting $550,000 a year and $30,000 every two weeks. That right there is what the kids need because Minor League Baseball doesn’t prep you for the big leagues. The big leagues preps you for the big leagues, minor leagues just gives you repetition.

It’ll be really tough to mentor professional young kids. Can I do it? Absolutely. Will, I ever shut the door? Absolutely not. But right now I think my niche is the amateur level because I can make some type of movement being in the amateur community versus being in the professional community.

When you’re a professional you’re not a part of the amateur universe and everything they have to do to become a professional. I want to be the guy who has everything to do with becoming a professional, and then once you’re a professional you take it to the next level which is being the best professional possible.

MMO: Looking back on your own career and experience with handling the pressures of being a number one pick, how do you feel you handled the lofty expectations that were placed on you at a young age?

Jake Roth/USA Today Sports

Milledge: I knew the expectations were going to come. I knew from day one what I was getting myself into; the contract that I signed, how to handle myself in the media, and how to talk.

As far as the expectations, as I said, I knew what I signed up for. I just always wanted to be the best player I could be. I wanted to be Lastings Milledge, I didn’t want to be David Wright or Jose Reyes or Willie Mays. I didn’t want to be those guys because each one of those guys does something different; they’re Willie Mays and Jose Reyes for a reason. That’s their name, that’s their product. They’re their own player.

I always grew up just wanting to be like my dad, so I really didn’t want to be anybody else but my dad. To have the success that my dad had and also be the player that I could be, that’s who I wanted to be like. I never really put pressure on myself or tried to deliver goods that everybody else wanted me to deliver. I just always wanted to deliver the goods that I knew I could do, and deliver the goods from the abilities that I had. Not the abilities that somebody else had, there’s no way for me to duplicate, replicate, or clone any other player that somebody else wanted me to be.

At the end of the day, I wouldn’t change anything that I did because it’s a win-win either way. Some of the things that maybe I could’ve done differently or done better if I would’ve been perfect, I would’ve never known that. I wouldn’t say I would do anything differently because I’ve learned such a valuable lesson on how to handle different situations and things like that. Of course, we can go back to 2003 or 2007 or whatever, yeah, I’ll have the answer key so of course, I’ll turn out better.

When life hits you from all different angles, when you get married and have kids, how are you going to adjust to that? Learning stuff at a young age and having a couple of bumps along the road, they’re good bumps. I never went to jail, I always stayed out of trouble and things like that. I was just always me so that was other people’s problem, it wasn’t mine or my best friend’s or the people who I dealt with. They never had a problem with me but everybody else did. As you say, you’re not going to make everyone happy, I can’t even make my own mom happy 100 percent of the time. [Laughs.]

The thing that I always did is I made sure that I did my job 100 percent. I can sleep at night and know that I played the game 100 percent and played the game hard every day. I had a passion for the game which some of that passion – quote-unquote – had some of you guys not liking me and thinking I was arrogant, which is okay. At the end of the day, I was happy and that’s all that matters.

I was doing something that I love doing. Something that I knew at a young age I was going to be in one way or the other. I knew I was going to play in the big leagues someday. I accomplished that so anything else I don’t really worry about what people write about me. It is unfair and it does suck. Have I cried? Absolutely. Have I thought the world was against me? Absolutely. At the end of the day, I’m happy. I’m happy with the way things started. I’m happy with the way things ended and I’m happy with what I’m doing now.

Anybody else, it doesn’t matter what you like. It doesn’t matter if you wanted me to be better than Willie Mays or David Wright, I don’t care. It doesn’t matter to you because you’re not me.

MMO: Your first major league home run on June 4th drew controversy for you giving fans high fives in the front row after you hit it to tie the game up in the 10th inning against the San Francisco Giants. Looking back at it all these years later, what are your thoughts from that game and some of the backlash you got over it?

Milledge: With me, I didn’t care. I didn’t care what anybody thought. That was if you wanted to say anything that I could’ve changed, yes, probably that. I was so naive to the fact that people could make something so negative from something that’s every kid’s dream.

Most people hit their first home runs when it really doesn’t matter. I tied it up in extra innings with two outs. It’s like, hey, how about anybody who’s writing negative stuff get to home plate, turn 97 mph around for your first time ever, at the pinnacle of the sport, on national television, on a national stage, and tell me what you would’ve done. Tell me if you would’ve done anything better.

I felt like it was right because three kids put their hands out and they actually wanted me to sign their ball when I was running out. I knew I couldn’t sign in the middle of the game, so I just gave them a high five. Then everybody gravitated down and then what am I supposed to do? A lot of people don’t understand that. If you look at the video – if they still have the video – you’ll see what happened.

The backlash is unfair but you can’t make everybody happy. Some people are not going to like it, some will love it. Some people are going to say they love it but really think you’re an asshole. It’s like, I’m not worried about what those people think. I know I did the right thing. I know I had an emotional moment and it was great.

I wouldn’t change anything about it.

Travel Japan Blog

MMO: You spent four seasons playing in Japan for the Yakult Swallows. How would you describe your time there and the major differences you found between MLB and Japanese baseball?

Milledge: Playing in Japan is ten times tougher than playing in the big leagues, and I’ll tell you why. Number one is the culture change. The thirteen-hour difference is so critical because it takes you roughly six months to get used to the first time I went there. The expectations are super high and the media is bigger because you’re a country now, you’re not just the state. You see it with all of the Asian guys when they come over. How much media follows Shohei Ohtani? How much media follows Masahiro Tanaka? How much media followed Dice-K and Yu Darvish?

The stage is actually bigger in Japan than it is in the United States, pound for pound. There’s no lower-level MLB team, no matter what team you play for, and no matter how many losses it’s still the pinnacle of the sport. If you take the lower end of the MLB, pound for pound, Japan is up there. The lower-end teams [in Japan] still drive in 12-15,000 fans per game. It’s louder and it’s just a bigger stage, honestly.

It’s such a world game, but over there, everybody’s Japanese except for the foreigners. That’s a difference in itself right then and there and there’s still some history and bad blood with Americans and Japanese, you see that quite often. More often than not they’re great people, and they want to see you do well. At the same time, you still have to deal with racism just like you have to deal with racism here, that’s no secret.

You have two spring training’s and practices are more in-depth. All in all, it’s just tougher on the body. In the big leagues, it’s super easy; everything’s laid out and everything is five-star.

It’s a stricter regimen [in Japan], it really is. It’s really tough, man. It’s not as easy as people think. Oh yeah, you go wash up in Japan, it’s like no, these guys are good. You’re paying the same guys who you’re saying is from a weak league, you’re turning around and paying their stars one hundred million dollars. So if they’re not that good, why aren’t you paying them $500,000?

That league is a very good league, and it makes it even tougher because of the strike zone. The strike zone is a lot bigger and the umpires are not as skilled as the big league umps. You’ve got guys like Ohtani that are getting three or four inches off the plate; good luck! When I was facing Tanaka, he was getting four inches off the plate in and out. Good luck!

It just goes back to the same thing that I said before, people speculate but they really don’t know the answers. I know the answers and a lot of people will look at me crazy and say no, but the talent level is less. Yes, pound for pound, player for player, yes. But what about the preparation? Who cares about the game, the game is the easiest part anyway. It’s the preparation, everything that goes on before the game.

I’ve got to do a walk and reflection at 11:45 in the morning. I’ve got to walk three miles and reflect on life and then I’m tired when I get to the field. It’s not just wake up, go to practice, and get ready for the game.

No, It’s waking up at 10:45, doing a walk and reflection at 11:45 and that walk and reflection take two hours. You go have lunch from 1 to 1:45, and then practice is at 3:00. Practice from 3-5 and then you’ve got an hour and a half left before you’ve got to go to the game. You’ve got to show up in the dugout an hour before the game because you’ve got to do four infield/outfield every single day, one hundred and forty-two times a year. Two Spring Trainings at 30 days a pop. You’re almost taking two hundred infields a year, that’s what people don’t understand. It’s extreme.

MMO: I can’t thank you enough for some time, Lastings. It was great to catch up with you and find out more about what you’re doing in your community. Best of luck with the facilities.

Milledge: Thank you so much, I appreciate it.

Follow Lastings Milledge on Twitter, @1stRdTraining

Visit Milledge’s site here.