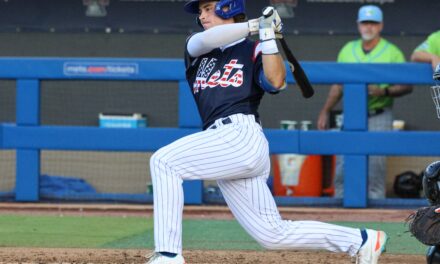

Photo by Peter Diana/Post-Gazette

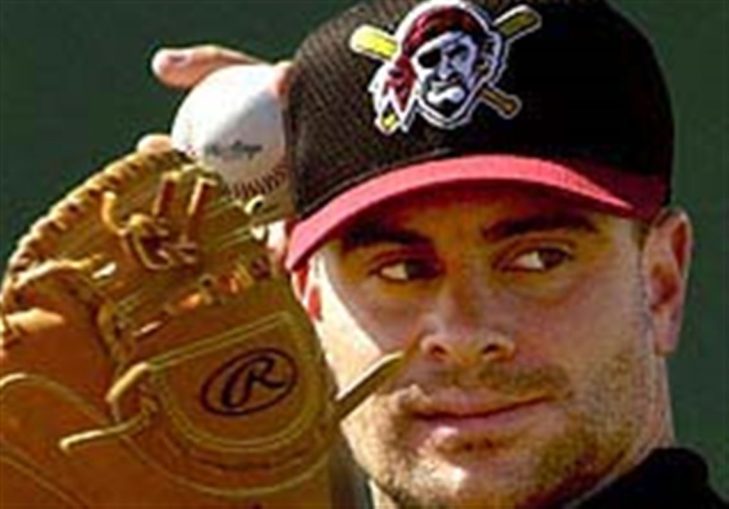

Playing fifteen years in the major leagues at the most grueling and demanding position in the sport, Jason Kendall knows the game better than most.

The three-time All-Star catcher had a front-row view of all aspects of the game; watching it unfold from his crouched position behind the plate.

The toll Kendall’s body took over the course of a productive, if not undervalued career could fill a WedMD page, yet he amazingly had only two seasons where he played in less than 130 games (1999, 2010).

Needless to say, Kendall was a throwback-type player, of which he took great pride in taking the field on a consistent basis and helping his team on both sides of the ball.

The word ‘throwback’ so perfectly encapsulates Kendall’s career that it was an easy choice as the title of his 2014 book.

Instead of writing a memoir – one that could easily be filled with anecdotes of growing up in a baseball family, catching the fifth-most games in baseball history (2025) and ranking fourth in hits among players who were primarily catchers (2195) – Kendall and co-author Lee Judge decided on a different route.

Throwback: A Big League Catcher Tells How the Game Is Really Played gives readers an inside view of the game from the unique perspective of Kendall’s baseball intellect. Each chapter focuses on a different aspect of the game; from a position-by-position rundown, to what the players discuss with the umpires to addressing the media pre and post-game.

Kendall, 44, offers an intricate glimpse inside the day-to-day life of a professional ballplayer, one in which he took very seriously. Kendall set a strict schedule for his daily arrival to the ballpark, noting that if he arrived late he’d be off his normal routine with a bad game likely to ensue.

Kendall was the ultimate creature of habit, ensuring that he had plenty of time to read over scouting reports, review video of the opposing team and speak in-depth to his starting pitcher that night. Kendall absorbed hitters’ tendencies, their subtle movements in the box and pitch sequencing like a sponge. In time, Kendall started calling his own games instead of the manager, ensuring his pitcher wouldn’t have to overthink on the mound.

The dedication in analyzing and preparing diligently was one of the reasons why Kendall was so successful during his career, highlighted in the fact that only three catchers posted a higher fWAR (FanGraphs’ WAR) than Kendall’s 39.5 from 1996 to 2010.

Since retirement, Kendall has served as a Special Assignment Coach for the Kansas City Royals, working with catcher Salvador Perez and acting as a liaison between the players and the front office. Getting the chance to stay involved in baseball and assist both on the field and with the suits upstairs has been rewarding for Kendall, who admits not paying very close attention to what was going on in the front office as a player.

The opportunity to learn the finer points of working in the front office and as a coach has been satisfying for Kendall, who is enticed at the prospects of one-day managing in the majors. For now, Kendall enjoys the work schedule, which permits him from rarely having to travel with the team and granting more time to be at home with his wife and kids.

It’s evident when speaking to Kendall that his trademark grit and ultra-competitive nature have far from dissipated, sounding as if he were preparing to don the catcher’s gear for tonight’s game.

The throwback label attached to Kendall is one of pride and merit, as years of learning to call his own game, gaining trust from each and every pitcher he caught and continuing to hustle until the very end warrants such a distinction.

I had the privilege of interviewing Kendall where we discussed growing up with a father who played in the majors, the biggest challenges to catching and his book, Throwback.

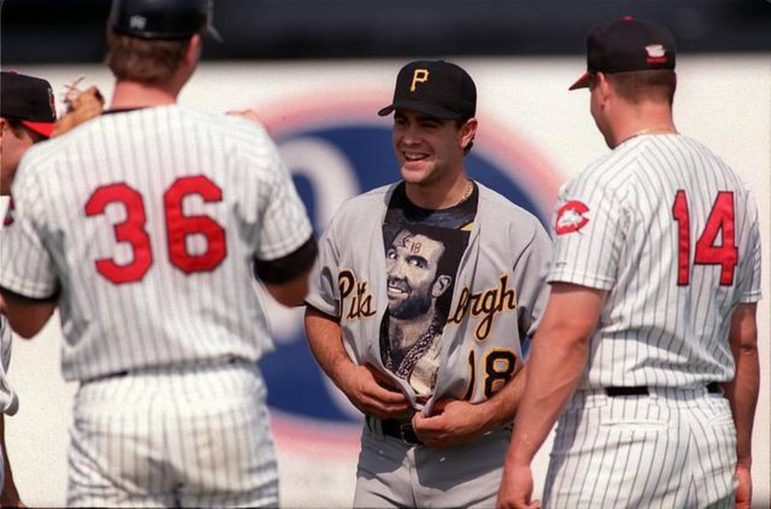

Photo by Robert Willett/News & Observer

MMO: Who were some of your favorite players growing up?

Kendall: I grew up in the game. My old man played for the Padres, Red Sox and Indians for twelve years in the big leagues. It’s funny, I had an interview with Eduardo Perez and one of the questions that was asked of me was: what do you think about Vladimir Guerrero’s son? I said, ‘You know what? You can ask anyone, you have an advantage.’

I got that question a lot coming up in the minor leagues: do you ever get sick and tired of hearing your father’s name in front of you? And I said, ‘Hell no!’ I’m very proud of what my dad accomplished and I had an advantage over everybody, especially in that era. That was when it was a game. Any son that you interview now that has a father that played in the big leagues always has an advantage.

They were talking about Vlad Jr. and I go, ‘This kid’s been around the game. From just the little things like instinct and how to act; that’s a huge, huge thing.’

So getting back to your question, number one would be my dad. But my second favorite player was Rod Carew.

MMO: You mention your father – Fred Kendall – who played twelve seasons in the majors. You talked about how much of an advantage it was to have him around to be able to pick his brain and get an early education in baseball. What do you remember from your dad’s playing days growing up?

Kendall: I watched my dad through the eras. He played from 1969-80, and I saw him go through several strikes and lockouts. He made more [money] as a coach than he ever did as a player. That’s what a lot of these players don’t know now, the sacrifice that these guys made to have the union this strong as we have it. I watched my dad go through strikes, I mean, he’d come home and work at UPS and in construction. Those guys sacrificed a lot.

Do I think what players are getting paid today is ridiculous? Absolutely. Am I an idiot and going to say no? Hell no! But it was because of those players before that went through the strikes and didn’t cross the line.

The younger players and the guys playing today are getting paid – I think the minimum now is $540,000 – and when I broke in it was $109,000. I’m with George Brett almost every day, and George told me it was about $20,000 for a rookie when he broke in.

MMO: At what point during your youth did you start honing in on catching?

Kendall: In all honesty, I never really caught. I caught once in a while in Little League.

I was a sophomore on the varsity team and my brother was on the team, too. My brother is a bigwig with the Giants now; he’s one of their major league scouts. I was playing with my brother and I was the starting second baseman and our starting catcher got into a fight and he was suspended for however many games.

Guys were running all over whoever the backup catcher was and our coach asked me if I could catch. I told him yeah. I always caught every once in a while in Little League but not every day until I was a sophomore in high school. Obviously, I had an unbelievable teacher in my father and, once again, an advantage to pick his brain.

MMO: What memories do you have from the 1992 MLB June Amateur Draft? Did you have any idea that the Pirates were looking to select you in the first round?

Kendall: I’m from California but I live in Kansas now, but in California, you play year-round. From the Area Code Games, the scouting teams, the Olympic Junior teams, you just can. You can’t do that out in Kansas because of the weather.

The games I was at I knew there were scouts there and I took all the tests. I mean, obviously, it’s changed now. Now you put on MLB Network and they do everything.

I knew that I had a chance and it wasn’t just the Pirates, it was a lot of other teams that were at the games. I’ve been in the room when they do it knowing what I know now as far as the front office part of it because I work with the Royals. Going into the draft room, everyone has their favorite guy and the scouting director obviously makes the final call. But the team before you might’ve picked him. It all depends on what the other teams do.

I knew I had a chance to go in the first round and I knew the Pirates were one of the teams. I remember I got drafted on a Wednesday night, had graduation on Thursday, and all my buddies and I went to Mexico for our senior trip and I signed within two days.

MMO: One of the amazing things about your career was how relatively healthy you stayed behind the plate. From your rookie year in 1996 until your final season in 2010, no catcher appeared in more games (2,085) than you did, with Ivan Rodriguez a distant second with 1,922. That has to be something you’re proud of from your career?

Kendall: It’s something I took pride in. Once again, growing up in the game and watching my dad play, you beat your body up. I took care of myself, I really took care of myself. I wanted to play, I loved this game and I loved playing.

I wasn’t a big catcher so even today if you ask [me] how my knees are, my knees are fine, it’s my arm. If I could throw a baseball I’d like to think I’d still be backing up somewhere. But I can’t throw it at that level anymore.

There are things that I’m proud of, I think I’m the only catcher to ever catch 140 games in I think it’s seven or eight years, no one’s ever going to do that now! It’s one of those things that I can always look back on but it was just I loved playing the game. I knew even if I was scuffling – if I was 0-for-20 – I could do something in that game to help us win.

I took pride in that. I like to think, and I know, especially as I got older, that there are younger guys that were like, damn, he’s playing again? Oh s***, I better get out there! I don’t like talking myself up at all, but I mean, it’s something that as an older veteran player you teach these kids that it’s a grind. Which it 100 percent is.

You’re with these guys more than your own family and you get into a place at 3 am and then you have a 1 pm game, it’s a mindset. If you’re mentally prepared to do that for 162 games, hopefully more making the playoffs, you’ll do it. It’s a big mind thing now; mentally being tough is dwindling in the big leagues now.

MMO: You talk about the mental side of the game. I spoke with Bob Tewksbury – who you hit your first major league home run off of – and is now the mental skills coach for the San Francisco Giants. He wrote a book on the mental aspects of the game and went into great detail on how players use various techniques to properly gear themselves for the season or a specific big game. Do you think that’s something that’s still a bit untapped in Major League Baseball?

Kendall: Without a doubt. A lot of these coaches today are just there to tell somebody what to do. Obviously, these players are making so much money and the coaches are worried about their own jobs, and I say some, not all. That’s kind of what I do now.

Take [Mike] Moustakas, and I’m just using him as an example, but run the ball out. You’ve got kids up there watching and the two easy things you can do in this game is be prepared and hustle.

It’s one thing to get to the big leagues, it’s very, very difficult. It’s another to stay for a long, long time. The game doesn’t owe you anything. Every ballplayer should know that and does know that because hell, I’d probably be a lifeguard or in jail if I wasn’t! [Laughs.]

I was very fortunate to play fifteen years in the big leagues and I don’t remember it, it went by so god damn quick! And that’s what I tell these guys. I say, ‘Guys, it goes by quick so enjoy every part of it. Make as much money as you can, play the game like it was supposed to be played, and play it hard.’

MMO: In 2014, your book, Throwback: A Big League Catcher Tells How the Game Is Really Played was released. Can you talk about the process of writing the book and how that all came about?

Kendall: Lee [Judge] was a writer for The Kansas City Star at the time, and it was my last year playing. There was a game and I can’t remember who had the game-winning hit or the game-winning sac fly, but there was a runner on second base, no outs, and Chris Getz was up. Getz got him over with a groundball to second base. Next guy gets a sac fly and we win the game in the ninth or tenth inning.

In the locker room I’m watching and I see one guy go over to Getz, and it was Lee. Everybody else was around whoever hit the sac fly and Lee was just hanging around afterward and he was the only reporter. Getz’s locker was right next to mine so I heard the whole thing. I said to Lee, ‘You know, you’re the first guy I’ve ever seen that has ever done something like this.’

We started talking, talking, talking and maybe a week or two later I go, ‘Dude, you should write a book.’

And he said, “Yeah, you want to write it with me?”

I go, ‘Hell no!’

I had blown my arm out again and had surgery and I was in the locker room when he said, “Well, I would love you to write the book with me.’

I told him I thought what he did was pretty cool because he examined the little things. The one thing about people today, especially if they don’t know the game, it’s a boring game if you don’t know it. You’re there for thirty minutes into the game and next thing you know you’re not paying attention. That always bothered me – the people that don’t know the game – because it’s the greatest game ever if you know what’s going on.

So, what ended up happening, Mat, was he wrote a bit and sent it to the publisher detailing what it was about. The publisher said go do it, and Lee said we had a book. Lee and I became friends and it was fun. It was more on the road when the team was on the road because I was rehabbing every day at home. He’d come over and we’d watch the games together and he’d set a microphone out and ask questions.

The only thing I wish I would’ve done [differently] with the book was publicized it more because I was still working with the Royals. I didn’t get out and publicize it. And I’ll be honest with you, I’ve read very little of it because I lived it. Everyone always comes up and says that it’s a great book and I’m like, ‘Oh, you like it? Cool man, thanks! Appreciate it.’

If there were only a handful of people out there that read it and didn’t know certain things about this game and they can go to the ballpark now and change their experience, [it’s worth it]. And if you do that it’s actually a pretty amazing thing.

Going to games now is so damn expensive for a family, but you can do it watching TV. It’s actually kind of fun and that’s all I know. I grew up in the game. Baseball’s all I know and it always bothered me when I heard baseball is boring. It is boring if you don’t know what’s going on. But if you know what’s going on and have an idea, then you can enjoy it just like anyone else.

MMO: I think it’s great that you overheard the conversation that Judge had with Getz and that you took the time to appreciate when a reporter noticed the small details of the game.

Kendall: And that’s what Lee does, and he still kind of does it now. I know that he got laid off last year but he still goes down to the ballpark. I think it’s more of a blog now then with The Kansas City Star, but he still does it. Lee told me he learned so much and I told him, ‘Lee, it’s not learning so much, it’s little things to look for.’ I don’t know everything about the game; nobody’s going to know everything about this game.

I had a bunch of managers that I played for and every single manager I played for you learn more things. Ned Yost, for instance, the manager of the Kansas City Royals that won a World Series three years ago, I had him in Milwaukee. He’d ask, “Jason, what do I do? Get him up? Get that guy up? Get this guy up?” If we lose or win [he’d ask], “What did he hit out?”

[I’d say], ‘Eh, it was two-seamer.’ And he took that stuff back to the media room and that’s what the reporters wrote down. I mean, I managed the game, especially when I was older.

I had a father who caught in the big leagues for twelve years, but it took me a good five years to learn how to call a good game. Watch a guy’s feet, watch his hands because a great hitter changes pitch-by-pitch. It ain’t night-by-night or day-by-day, if you’re a .300 hitter you change pitch by pitch.

Joe Mauer – who I put in the book and used as an example – you throw him a 2-1 changeup a month ago in Minnesota, and whoever the pitcher might be comes to Kansas City and he gets a 2-1 count, he’s sitting on that [change]. That was the beauty about catching, I would know that.

Everything’s on a computer now, all you have to do is click a button and see counts, stats, what did he hit, when he swings the most, etc. That’s another thing that bothers me is the catchers that don’t put in the time to do that now. If I got to the ballpark at 1:01, I was late, my whole day was screwed up. You have to have a routine nowadays and so I would make sure I was prepared. You’ve got to get that trust with your pitchers and have them see you busting your ass.

That’s another reason games are so damn long is because some of the catchers now – I’m not saying all of them – but some of them are showing up the ballpark at four when stretch is at 4:30 and that’s why you see pitchers calling games. Pitchers shouldn’t be calling games, they’re not there every day, they don’t see what a catcher sees.

Getting back to my point, being the manager catching-wise, absolutely. Managers can’t see what you see from the dugouts. They cannot, it’s impossible and that’s why the manager/catcher relationship has to be good because then you have a catcher that actually cares and wants to win and do everything to be prepared.

MMO: You mention that it took you a good five years to learn how to call a good game. What was the most challenging aspect of getting a good grasp on calling a game?

Kendall: I mean, it was just watching, knowing what happens from a year ago. What did this guy do on a 1-1 pitch? When I first started it was VHS tapes. Which is funny, because you feel kind of old. But I don’t think that I’m old because I’m 44. You would go off of that as much as possible.

Obviously, your pitching coaches would help. Your guy out there – Dave Eiland – I respect Eiland and I’ve seen what he’s done firsthand with the Royals over the last few years. He does a lot of work and he has to do a lot of work now because some of the players today –not all of them – they don’t do the work. They show up at four. When the catcher’s looking over with a runner on first and they’re looking for the fundamental signs or to throw over, the manager doesn’t know. You know he might go on certain counts but you can see it, you can sense it and feel it.

Ned Yost allowed me to run everything in Milwaukee. It was the best year I had defensively and the games were quick and we ended up going to the playoffs. That was the year CC Sabathia came over and was like God; pitched on like three-days rest. I ran everything and they just talked to the media.

It was one of those things where you have to put your time in and show that you can do that over the course of how many years. I’m sure Yadier [Molina] does that now because he knows what’s going on. You have to earn it.

MMO: What percent of catchers in baseball today call their own game?

Kendall: It’s such a dicey question, I would say it’s 50/50. It’s a big, big trust thing. That being said, if the pitcher has a good feel for the ball in their hand, when that happens you go out there and say, ‘Hey, I think your curveball is a good pitch here. But I don’t have the ball in my hands. You want that two-seamer? Got it, go for it. But you better bury it.’

You don’t want them to think. How many catchers will do that today? In my last six to eight years, I was like, ‘This is what you’re pitching. I know what I’m doing, I’m the one who sat my ass down for three hours and studied this! Make your pitch.’

I told my pitchers don’t think, let me do the thinking for you, it’s what I‘m here for. Especially young or older guys, I got it. The games are quicker, the trust level just goes up with everybody from the bullpen on, and there’s nothing better than having that on a team because the game will go by quicker.

The fact that Joe Torre and Rob Manfred are talking about taking out mound visits, if your catcher has any idea what he’s doing, go ahead and take them out. That’s fine. But that’s not the reason why the games are so slow. Obviously, you have the commercials in between blah, blah, blah. You speed it up to slow it down, and then you tell the umpires to wait for TV now.

MMO: One particular topic you mention in the catching chapter of your book was on pitch framing. You’re not a proponent of it, and you mention that if you were looking to steal a pitch, you’d subtly shift your body when making the catch instead of exaggerating with your glove or by holding the ball in place.

Obviously, pitch framing has become a big metric for analysts and sabermetric fans over the years for trying to find value in catchers. I’m curious, what you would suggest for fans to look at instead when evaluating how well a catcher is doing defensively?

Kendall: If the catcher goes unnoticed throughout a game defensively then they probably have done a pretty good job. That’s why I never, ever took my mask off. I always wanted to go unnoticed.

As far as the analytics, I think there are some good things. But I honestly believe there needs to be a mediator for the old school people to the analytics. There are some great things with analytics and obviously, with the old school guys it’s the way the game was played and the game is changing so you have to learn to change with the game. It’s one of the things I’ve learned over the last five or six years.

Getting back to your question, I’ve never liked pitch framing. Just catch the ball where it’s at. As a fan, if you’re looking at the game, I don’t know the younger umpires now. The umpires that are still around when I was playing, just catch the ball. Now with the younger umpires, I don’t know. I don’t know if they’re looking for you to snatch the ball or frame it. And you know it’s different words, the word framing to me, I don’t like it. Is there such thing as pitch framing? I mean, I say just catch the ball. Is that framing? I don’t know. I just don’t like the word. Just catch the ball where it’s pitched at and the veteran umpires, you’re going to get that [call].

To a fan, say Joe West is behind the plate, I’m just using him as an example. Yeah, he’s grumpy, but I’m going to tell you, Joe West is one of the best umpires that there is today. He’s consistent. He’s not going to give you snatching this ball and framing this one, he’s not going to do that.

For a fan, see who’s who’s behind the plate. If there’s an older umpire behind that’s been around for ten years, he’s probably going to go with where the catcher catches the ball. The whole snatching part and trying to get back into the zone is probably not going to work with them. The younger guys it might work, I don’t know what the younger guys think of the analytic stuff.

The whole QuesTec thing, where they started to get graded, started screwing up a lot of things for them. Every umpire had their own zone and the catcher, pitcher and hitter knew it. You knew who was wide and who was small.

When it first came out there were only six stadiums that had it, and Oakland was one of them. I could totally tell when guys were coming to Oakland or whatever stadiums that had it, they would change up a little bit because they were getting graded. Now I think that’s a good thing because you need to be accountable just like players need to be accountable. Then the next thing was all the analytical stuff popping in now and the umpires are under a microscope, as they should be like the players.

That was when it started zone-wise and people were saying framing this, framing that. They’re not framing, it’s just the umpires’ zones. Everybody knew whether it be big or small, it had to start changing because whenever that four-man crew went into that city, they knew that thing was behind them and they were getting graded on it.

MMO: One story I found interesting in your book was in the outfield chapter, where you talk about a time when you called the game from left field for the Pirates’ backup catcher, Keith Osik. How did you make that work with relaying signs to Osik from left?

Kendall: I was in left field and when my glove hand was down it was a two-seamer. If my glove hand was up it was a fastball, if I remember. If my right hand was down it was a curveball, slider or changeup.

Honestly, and I’ll never forget this, the thing with my thumb is what really jacked up my whole offense. I tore my thumb and they jacked up the surgery and to this day I could barely move the damn thing. But I’m in the outfield and I never had a chance to work on the outfield because when I wasn’t playing [there] I was catching. The Pirates decided to give me a couple of games so I’d go out and work on it during BP.

I’ll never forget my first or second game in the outfield. Quilvio Veras hits a ball down the line and I slide and make the number one web gem, but oh boy, did it go downhill from there. [Laughs.] The reason I said that was because fans are yelling at you and then the next thing you know the ball is behind you.

The one thing you cannot do when you’re catching is listen to anything that’s going on. That’s why I told Keith, ‘Listen, let me call the game from the outfield because I’ve got to stay in this game. I’ve already made like five errors in six games and I can’t do that anymore.’

MMO: I’m just surprised no one on the opposing team saw you flashing these signs from the outfield.

Kendall: Nope. When I was with Milwaukee – and this is getting back to what you just said – Mike Cameron and the good outfielders, they wanted to know if an off-speed pitch was coming or a fastball. That’s another thing nobody really knows. The whole year nobody even knew if I called a pitch and put my glove down on the ground afterward, it was a breaking ball.

I would see Cameron in center field cheating, and if it wasn’t and I kept it as a fastball I’d just keep it up by my knee. But he wanted to know that so he could get a jump on it.

MMO: Since you retired as a player, you’ve worked for the Kansas City Royals as a Special Assignment Coach. Can you touch on your role with the team?

Kendall: I’m down in the locker room, I don’t have to go on the road. The only road trips I’ve made in the last six years were the Giants in the World Series, the Blue Jays in the ALCS, and the Mets in the World Series. I’m raising a family and I know that my dad didn’t have the money. We couldn’t go everywhere he was going because they didn’t make that much money. So I’m not going to do that to my children because my kids are first.

I go there early usually at one. Go over the scouting reports with Sal [Perez], and he’s as hardheaded as they come. It’s a new generation and I’m changing with it so I go over any and everything. Okay, why did you do this? With the pitchers, why did you throw this pitch here or there? Hit some fungos and then I go sit up in the suite with Dayton [Moore]. It’s a great gig.

I’ve learned so much from what I’ve been doing because when I was playing and went to the ballpark I didn’t give a rat’s ass about the front office or the owner. I was just worried about what I had to do that day to help our team win and be prepared. I’ve definitely learned so much in the last eight years. I go there and I’m kind of a fallback for Dayton and Ned [Yost], so they don’t have to do the little things.

MMO: Your resume as a player certainly must help grab the player’s attention more and give them more reason to listen to you.

Kendall: Without a doubt. I definitely have the resume and I’ve been there and done that. I tell them I’m not getting on you, I’m just trying to help. Eric Hosmer would come pick my brain all the time. I’ve watched these guys from kids to grown men now. They won a World Series and you watch them grow up.

Part of you is like, well, they took something here or there from me. Watching how professional they are now it’s cool. That’s the cool part of coaching.

MMO: Do you ever envision yourself as a manager in the majors one day?

Kendall: I’ve had numerous opportunities. I’ve turned down some interviews over the last five years, which I know I would bang out. But it’s a grind; I’ve done that grind for 28 years in professional baseball.

Maybe when the kids are gone; my daughter’s 11 and she’s the youngest. Maybe, I don’t know. I know that definitely over the last five years I’ve had big-league interviews that I’ve turned down because I don’t want to do it yet. Do I want to do it later? I don’t know. I’m a dad, I’m a dad right now. As I said, my mom raised us because my dad was gone all the time. I’m not going to do that to my kids.

MMO: Before we started the interview, you asked me to remind you about a story on the union. Can you share that now with the readers?

Kendall: This is what’s wrong with the union and what guys don’t understand. They had their union meeting and at least on our team – I can’t speak for all the other teams – had only two guys out of the fifty or so we invited to spring training that knew that the union turned down the 26th man. Which obviously opens up thirty jobs and you have that filter effect down to the minor leagues, but instead they got nutrition. Every team and minor league team in the organization has a weight coach, and when I was playing I didn’t know too much about the union. I knew there were guys taking care of it. Greg Maddux, Al Leiter, Craig Counsell, etc.

You had guys that went to every single meeting, knew what was going on, and said, “No, we’re not doing this.” I don’t know if that’s the case now because the fact that they passed up on the 26th man, that could that help out a bullpen or help out that one game that might get you over the hump. Plus, you’re opening up thirty jobs. And they said no because they wanted to have f****** eggs, egg whites, fruit and the nutritionist looking over them. I’m sitting there going, no way.

Tony Clark’s a great guy, played against him, a great guy. My dad was actually his coach with the Tigers when he was there; he’s just a classy guy. But it just makes you think that maybe they do need a lawyer. The union is one of the strongest in the world because of the people that came before it.

Like I said, I’m not really involved in the union, I probably know more about what’s going on now than I did back then because there were twenty veteran guys that were not going to let s*** go by. We didn’t’ have to worry about stuff like that. I don’t know what’s going on now as far as that. But to pass up on a 26th guy is a huge, huge thing for this game.

MMO: Think about that minor league player who is on the bubble, too. A guy who could be an extra bench piece or bullpen arm; the difference in minor league salary to the minimum in the majors is extraordinary.

Kendall: Oh yeah, it all trickles down to maybe giving that one guy another shot. Maybe they give him three of four at-bats a week or play him two games in a row to see what he really has. Just little things that people will never, ever think about. And obviously, the union didn’t think about it either.

But they’re all eating apples and you’re a grown man, if you don’t know how to take care of yourself at this level, you probably shouldn’t be in the game. And that was a huge thing. I remember my dad saying, “You don’t go to the ballpark to eat, you go to the ballpark to work.” From coaching staff to players, they’re all eating breakfast, lunch and dinner there, and basically not paying for it because the union said they didn’t have to pay.

The fact that there were two guys in our organization in spring training that knew there was a 26th man passed up, means somebody is not doing their job. Two guys. And there was one kid who went to me and asked, “What is the union?” I had to sit this kid down for thirty minutes and explain to him what it is and to me, that was a big thing.

MMO: I can’t thank you enough for speaking with me today, Jason. I really appreciate the time and looking back on your career.

Kendall: Absolutely, man. Be good.

Follow Jason Kendall on Twitter, @jasondkendall18

Purchase Kendall’s book Throwback: A Big-League Catcher Tells How the Game Is Really Played here.