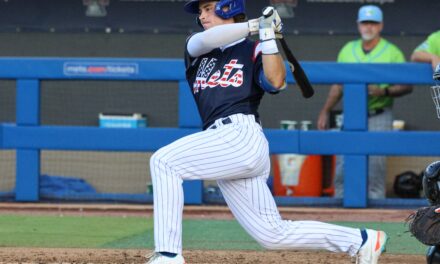

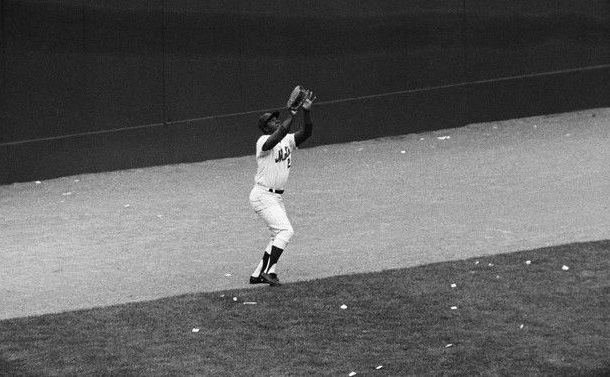

When Cleon Jones squeezed his glove around the ball that Baltimore Orioles second baseman Davey Johnson hit to left field in the top of the ninth in Game Five of the 1969 World Series to give the Mets their first championship in their eight-year history, it was something he never dreamed of doing.

For Jones, making it as a major league ballplayer from his hometown of Africatown, a historic community located just several miles north of downtown Mobile, Alabama, was a dream in and of itself.

After all, the Mobile area was a hotbed for athletic talent, as players such as Satchel Paige, Hank Aaron, Willie McCovey, Ozzie Smith, Billy Williams, Tommie Agee, and Jones all grew up playing ball in the area. The talent was fierce and there was a bevy of competition that even Jones surmises that part of the reason he was able to make a career as a big leaguer was being in the right place at the right time.

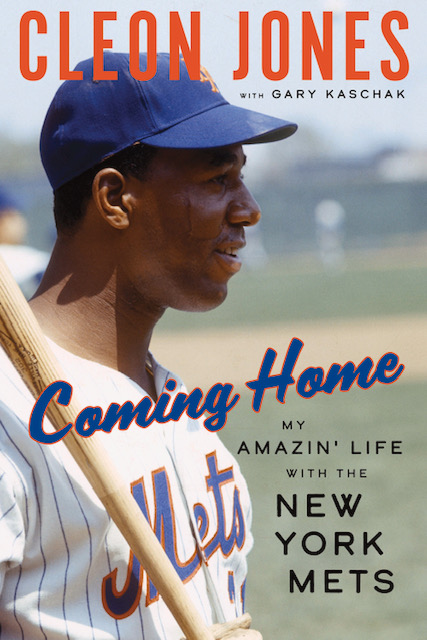

Jones, 80, reflects on his hometown and the special connection it had and still has to this day in his new memoir, “Coming Home: My Amazin’ Life with the New York Mets,” released August 2 from Triumph Books.

Triumph Books

In the book, Jones details his childhood in Africatown, being raised by his grandparents after his parents left him and his brother to find work, pursuing both baseball and football, and eventually signing with the Mets and becoming a world champion in 1969.

Jones’ memoir is filled with personal anecdotes and arduous moments, including a car accident that ended his pursuit in a career in football to some of the unjust and despicable racist moments he endured.

His major league career lasted thirteen seasons, twelve with the Mets, and he posted a career .281 batting average with 93 home runs and 524 RBIs in 1,213 regular season games. Among all time Mets, Jones ranks sixth in games played (1,201), fifth in at-bats (4,223), fourth in hits (1,188), tied for eighth in RBI (521), and tenth in extra-base hits (308).

Jones’ 1969 season was his standout year, as he posted career highs in average (.340), OBP (.422), slugging (.482), hits (164), RBI (75), and fWAR (6.3). Jones’ 6.3 fWAR was the seventh-highest for an outfielder in that season.

Post retirement, Jones and his family moved back to Africatown and have done their part to help restore a dying community. When Jones was growing up, he estimated that around 10,000 to 12,000 people inhabited that area, now, that number has plunged to around 2,000 people.

With his non-profit, The Cleon Jones Last Out Community Foundation, Jones and his family are looking to raise funds to help build and refurbish homes, combat blight, and provide programs and opportunities to those who wish to make this place their home.

I had the privilege of speaking to Jones prior to the book’s release, to discuss his memoir and detail some memorable moments from his life and career.

MMO: What prompted you to write the book now?

Jones: It was a family matter. Sitting around the kitchen table talking with my wife and two kids, Anja and Cleon Jr., we often talked about the neighborhood and baseball. Each time we sat and talked, I would add something different and new, and they said, “We never heard that before. You need to put together a book.” And I said, “I don’t think so.”

Finally, they talked me into putting a book together. After reading it myself, I think there’s some good information and people know who I am. I think it was a great idea.

MMO: A main theme in the book is your home and community. Can you talk about how your hometown helped shape you into the man and ballplayer you became?

Jones: I come from a historic neighborhood in Africatown. We always reference Plateau Africatown as our neighborhood. Coming up here there were some great ballplayers that came up with and before me.

I was lucky that I grew up in Africatown because the family unit was intact at that time, and all the families around me had eight, nine, ten, eleven, or twelve kids! One family had nineteen and another had twenty-two. Most of them were boys and when I came out of my front door, if I was lucky enough to have a ball, and I threw it up before it came back down I had enough for two teams.

We were able to play baseball in the schoolyard and on the field and we played tops. A lot of folks might not realize what tops is: you get a broomstick and take soda tops and you hit the soda tops, which is a difficult thing to do. I think we mastered that.

When I came up, Africatown was a neighborhood of about 12,000 people and consisted of Happy Hills, Kelly Hills, Plateau, Magazine, Magazine Point, and Lewis Quarters.

I keep emphasizing this because it’s important, the family unit was intact, and that was because of the availability of jobs. We had two paper mills around us, International and Scott Paper Company, we had Alcoa Aluminum, and we had other mills that people could leave home in the morning and it wouldn’t take them more than five to ten minutes to get to. As a result, the family unit was intact, and that was important at that time.

I grew up with my grandmother and great-grandmother; my mother and father had moved on for the very reason that I just talked about: seeking work. I was raised by my grandparents with an older brother who’s two years older. He was also good athlete.

Having people like Satchel Paige and Hank Aaron, and a guy named Ralph Donahue, who was a pitcher who went against Satchel Paige here in the Mobile area. They pitched until dark. They were striking out everybody, that’s how good both were at the time.

We know who Satchel Paige went on to be: one of the greatest pitchers ever to live. This other guy was a neighborhood guy that lived and talked about all the great things and reminisced about being as good as Satchel Paige. Guys like James “Fat” Robertson, who managed our local team and funded us bats and balls and a place to practice and play, enhanced my skills as it relates to baseball and getting to the big leagues.

Africatown still exists. We found the Clotilda, that’s the ship that brought the last cargo of the would-be slaves to America, and it ended up here in my hometown. A couple of years ago we ended up finding the ship, a local writer, Ben Raines, actually found the ship. That history along with all of the baseball makes it a dynamic place.

As I stated earlier, there were about 12-14,000 people in my neighborhood, now it’s only about 2,000. We are a dying community with the average age probably being about 60 years old in the community.

My family has been fighting for years to try and do some things to entice people to move back in to try and grow the community, and let the world know about Africatown and its historical significance as it relates to this country.

MMO: From reading your book, it seemed like that area was filled with a ton of athletic talent.

Jones: No doubt about it. Everybody asks, “Were you the best player in your community?” The answer is always no. There were guys whom I wanted to be like; guys that were my age who were much better. I was fortunate that I got a chance to play and some of these guys just didn’t get the opportunity to.

I’ve always had a mindset that I would keep in touch with all of these players, because these guys I’m talking about who were so talented inspired me and made me, so-to-speak. I just got up every morning and worked every day to try and be as good as those guys.

I can think about all the other hundreds of guys who I came up with who were better, in my opinion. You have to be in the right place at the right time, I guess. I give all the credit to my community and the people in the community and that’s why we’re here now fighting back.

We never had an illusion as to where we’d live after baseball, so we came back home and we’ve been fighting for over thirty years to make this community what it really should be. And I’m not just talking about athletics, I’m talking the historical significance, building homes, refurbishing homes, and making sure people are educated about who they are and the history.

Those things are beginning to happen but it has taken all these years to try to put things on the right track.

MMO: And that’s what your non-profit, The Cleon Jones Last Out Community Foundation, is all about, right?

Jones: That’s exactly what we do each and every day. I’d like to give a shoutout to my family again, as they enticed me to put this together so we can raise funds to put roofs on peoples’ houses, refurbish their homes, whether it be paint, windows, doors, new floors, and things of that nature.

We are right now trying to put together some cohesive unit where we can start building houses. If you build houses, you can entice young folks back to the community and that’s certainly what we need.

As I stated earlier, we are a dying community and there’s a lot of interest in it; we get knocks on the door asking if there’s any land available and if they can build a house.

We are working towards all of those things and we have to look out for the homeless and senior citizens. This community is engrossed with senior citizens and people over 70 and we have two people over 100; one is 101 and the other is 102. We have many that are up in their nineties.

Longevity lives in this community and we just want to make sure we can entice some young folks to come back and build. That will help our churches, our schools, and things of that nature. We have a plan and we just have to implement it. Everything costs money and certainly it takes some time but that’s why we are here.

MMO: You write that you were a natural left-handed hitter but that changed early on as a kid. What prompted you to start hitting right-handed?

Jones: Sometimes things happen for the best. Where we played, I was a left-handed hitter and we only had one ball. I used to hit the ball into the marsh down the right field line. And so, they told me if I was going to play, I couldn’t hit left-handed, I would have to hit from the other side because I was losing their ball and they didn’t have any.

I got on the other side and started to play with that and just never went back to the right side. [Laughs.] I was a left-hander from six years old up until around thirteen or so, and then I never left. That’s when I started to play with the big boys.

MMO: Along with baseball, you played football at A&M and were getting letters from the Cleveland Browns. You got into a terrible accident, and you write that the accident changed everything for you and that’s when you decided you were done with football. Can you talk about that experience and how that eventually led you into a career in baseball?

Jones: People have an opinion about who you are, what you can do, and what you’re good at. Certainly at the time I was considered a better football player than a baseball player.

I came home from a break from school and got into an automobile accident. A car hit us head on and I went through the windshield. As I think about it, people looked at me and were hollering and crying, and I didn’t feel anything at the time. The lacerations were so gross, I guess, that people looked at me and were crying.

I was pronounced dead two or three times, I lacerated my eyelashes, lord know why it didn’t put out my eyes. God is always at work. They took me to the hospital in an ambulance and the doctors were staring over me and sewed me up and whatnot. A friend of mine worked at the hospital and I could hear his voice asking the doctor if I was going to make it. The doctor said, “If we can stop the bleeding, we believe he’ll make it.”

Everybody thought my career in both football and baseball was a thing of the past. I didn’t go back to school, but I ended up a month or two later starting to work out with baseball.

Two months later, I signed a baseball contract. I was going back to school and the Mets called me wanting me to go to instructional league in 1962. I went down to instructional league and had a great year, and that was the same year Ed Kranepool signed. He was a bonus baby that year. I got a little money but that’s because they told me they didn’t have any more money because Kranepool got it all. [Laughs.] We talk about that all the time.

That’s probably the best thing that happened to me after the accident that I was able to go to winter ball because the two of us ended up being the best two players on the roster. I was touted to go to Triple-A that year, and that was a big jump from just signing to going to Triple-A. I had another setback where I had a hemorrhoid problem and I needed to get surgery on that and that set me back another month. That all happened when I was in Auburn, New York, in A-ball.

I ended up coming home and having surgery and went to Raleigh, North Carolina, in I believe July and I ended up going to the big leagues after that season. The accident didn’t stop me because God was in the mix and here I am again doing God’s work.

MMO: What are your memories from being scouted and eventually signing with the Mets?

Jones: The Mets had scouts out. A scout named Julius Morgan came to Mobile to see me. A guy named Clyde Gray (friend and sort of agent, as Jones writes) and his wife wrote the Mets that they had a player who was going to be a big-leaguer and that someone needed to come to see him.

The Mets sent Morgan and when he came to see me, we were playing a Sunday game after church. The first time up I hit a home run and then it rained. [Laughs.] He didn’t get a chance to see me but that one time at bat.

Clyde Gray and I went to Salisbury, South Carolina, to work out. We went to Carolina a week or two later and worked out and he liked what he saw and so did the other managers. They offered me a contract up there for $15,000. I told them, ‘No way am I signing for $15,000. [Tommie] Agee just got $65,000 and Kranepool got $100,000. I’m better than both of them.’ I said no and we came back home.

When I got back home the scout was sitting on the porch talking to my grandmother. My grandmother always had the last word. She said, “This man is trying to give you this money and you’re acting a fool. Boy, if you don’t sign that contract you’re going to have to deal with me!” That was the end of that. I signed the contract because grandma said sign it and it was the best move that I ever made, that grandma made me make. [Laughs.]

MMO: You write how you would regularly seek advice from several veteran players on the Mets, including Warren Spahn, Al Jackson, and Ken Boyer. What were some of the things you wanted to take away from them, and how did they aid you in becoming a better ballplayer?

Jones: It’s always good to know where you’re headed and how the other guys got there. Spahnie was one of the best left-handers ever, he was full of knowledge. Al Jackson was like a big brother to me, he just showed me the ropes and kept my mind focused on how to get to the big leagues and stay in the big leagues. Ken Boyer was a gentleman’s gentleman, and so was Jackson.

I was fortunate enough that Al Jackson was my roommate. Al showed me the ropes on pitching, how to concentrate on what it is you want to do and gave me all of the particulars on and off the field. I’ll be forever grateful to Al Jackson.

The good news is that the Mets were the kind of organization that tried to get friendly people to be teammates and to rally around one another. It wasn’t quite there at that time, but I keep mentioning this name all the time in Johnny Murphy. He was assistant general manager at the time and became the general manager, and he was the glue to the organization as I saw it. He had the foresight to put me with Al Jackson so I could learn from Al and certainly that worked out.

I learned how to concentrate on what it was that I wanted to do and take charge. That’s what we talk about all the time: being in charge of who you are and not being in limbo as to what you wanted to do and know what you want to do at all times. That’s a big factor because all great hitters, and I’m not saying I was a great hitter, like Ted Williams, [Stan] Musial, [Willie] Mays, [Mickey] Mantle, Aaron, all these guys took charge when they went to the plate. That’s what a young player has to know, that he has to take charge.

There’s a way that you can do that but it just doesn’t happen. If you are a good fastball hitter don’t get beat by the fastball by taking it. That’s what I concentrated on was taking something away from the pitcher; if I take the fastball, I give you the curveball up until two strikes. It’s not just going to the plate with an empty head and a bat in your hand. It’s going to the plate with a bat in your hand and a mindset.

That’s what you learn from older guys, and I don’t know if baseball is that way now or not, but we shared the game when I played.

MMO: One of the things I found interesting was when you wrote about how you were one of the few players who would regularly watch film before and after games. When and why did you start doing that, and how did that help you with your play on the field?

Jones: I was always interested in mechanics. Often your mechanics cause you to go into slumps. And the other thing is that the baseball is the key. If you focus and you react to the baseball, whether it’s offensively or defensively, then you’re going to be in control.

A lot of guys don’t know when to react and don’t have a trigger for reaction. What I mean by that is the release point, or where the pitcher releases the ball is where you take over. It’s the same thing for the outfield, you can’t go for the ball until you see it come off the bat. You can’t hit the ball until the pitcher releases it, so it’s release point and the ball tells you what to do.

You have to be able to react to the ball when it’s in flight, whether offensively or defensively. Those are the triggers that you deal with. A lot of players never learn that, and as a result, they don’t get better, and they struggle throughout their careers.

MMO: When I say the name Gil Hodges, what comes to mind?

Jones: In my opinion, he’s the best manager I played for. Casey Stengel was a great manager because he had all those great teams with the Yankees, but Gil was the best manager because, we’ve been talking about preparation and being prepared, he was always prepared. What I mean by that is he coached every area of the game. He was good with pitchers, good with position players, and good with bench players. You might ask, how can he be good with bench players? If you talk to your players and you’re telling them that you don’t know when they’re going to be called on, but you have to stay ready and ready to react when you’re called on.

I think everyone knows that we only had four starters on that ’69 team: Agee, [Jerry] Grote, [Bud] Harrelson, and myself. Everybody else platooned. You win a championship with a platoon team [and] that speaks volume when you don’t have the kind of power that the Yankees had and other teams had that were great teams.

We had great pitching and what we don’t get credit for is that we had great defense. We didn’t beat ourselves, you had to beat us. And that was because of Gil Hodges. He allowed us to make mistakes, and if you made a mistake, he wanted to make sure that you knew what you did so it wouldn’t happen again. He would drill you on those types of things.

If not for Gil Hodges, we wouldn’t be talking about the 1969 Mets. He made that team and brought this team together and told us in spring training that we were better than we thought we were. We all looked around at each other and said, “What is he talking about?” [Laughs.]

He was a real force on the team and everybody respected him. I wouldn’t say everybody loved him because he had his ways that he dealt with players in a sergeant manner. But he was always cordial and he always talked to you with a smile. Even when he walked out onto the field and got me that day (when Hodges removed Jones from left field on July 30, 1969), he had a smile on his face. Even that moment he had a plan, and he came to the ballpark with a plan each and every day and that’s why we won.

MMO: It seems that Hodges was a manager ahead of his time in many respects.

Jones: He could’ve managed at any time, but these players today wouldn’t fit with Gil. They would have to come down a notch or two to be on his team. Certainly, he would get them there, but they’re a little bit different today. He wouldn’t allow guys that struck out a whole lot to be hitting 3-0 and all those things. He had rules and these guys don’t seem to have rules anymore; they just go up there swinging.

There was a time where I was hitting about .360, and if you were 3-0 you had to take a pitch. I said to him one day, ‘I’m hitting about .360, don’t you think it’s about time to let me hit 3-0?’ He laughed about it and said, “Yeah, you’re right. You can do it, go ahead.”

He was in control, and when I say in control, it was Gil Hodges’ team and he managed it in a way that I hadn’t been a part of with any other manager. Like I said, he was good with pitchers, he was good with position players, he was good with all the players.

I see a lot of managers today that go out to the mound to pull a pitcher out and it’s already too late. We used to say why close a barn door when the horse is already out and gone? Gil was always a hitter or two ahead of the situation.

MMO: You mentioned that Hodges told the team in spring training in ’69 that you all were better than what you thought. At what point during that season did you realize something special was occurring?

Jones: In July we were having fun because we were winning. We knew we were getting a little bit better even though we knew the Cubs were up eight or nine games. We knew that we were getting better, and our pitching staff was growing and gaining confidence. We were gaining confidence as a team.

It was fun to go to the ballpark because we were winning, and he (Hodges) taught us how to win. We were confident that we could win every ballgame because there were very few games, except when we played Houston, that we were out of. And what I mean by that is if they were up four-five-six runs, we would fight back.

I don’t know how many one-run games we won that year, but I talk about it in the book how that made a difference. Even though we ran away with the lead at the end, it was because of Gil pushing everybody to be the best that they could be.

MMO: Your ’69 season was incredible, as you posted a .340 average and .422 on-base percentage. Was there anything specific you worked on or altered to raise your average and on-base as much as you did from your ’68 season?

Jones: After ’68, I knew that I could hit .300 in the big leagues. I got off to a slow start that year and I went down to the last day being able to hit .300 and I ended up hitting .297.

I made a pact with myself in ’69 that I was going to get off to a good start. I worked hard to get a good start, come out of the box ready and to have my average up to respectable. It worked for me because for the first three or four months I led the league, and when I cracked my ribs, no doubt in my mind I would’ve won the batting title that year.

Before I cracked my ribs, I was going up and I was just feeling better at the plate. Nothing was fooling me and getting by me. I was having three or four good at-bats each and every game. I was just on my game because I was in control.

MMO: That goes back to having a mindset at the plate like you talked about before.

Jones: I knew what happened my at-bat before this particular at-bat and what he threw me, and I knew if I made out and if I got a hit what I hit. I would deduct from that what I would probably get. It worked most of the time because pitchers have a book on players of what they think they can get you out on, what part of the plate and if they can pitch you inside or outside, up, or down. All of those things.

You can’t go up there thinking about that, but you have to. You have to understand that to be in control you’ve got to minimize all of those things and take one that you can deal with and move forward.

MMO: What is it like to catch the final out of a deciding World Series game?

Jones: I never even thought about it before it happened. You go out to the outfield hoping and feeling that this is the last inning and we’re going to win. You never dream that the last out is going to fall into your glove and the last ball would put a staple on your career. Having been the last out of the 1969 World Series and you’re the guy that caught the ball.

I never had that kind of dream but it’s now something that I’m noted for along with the shoe polish deal. It was the greatest catch of the game. [Ron] Swoboda made great catches, Agee made great catches, but that was the greatest catch of the game. It just sealed a great year for a great organization.

MMO: Another subject you tackle in the book is some of the racism you dealt with in your life, and how you navigated through some awful moments. How were you able to stay so mentally tough and navigate through such cruel and awful racist times throughout the course of your life?

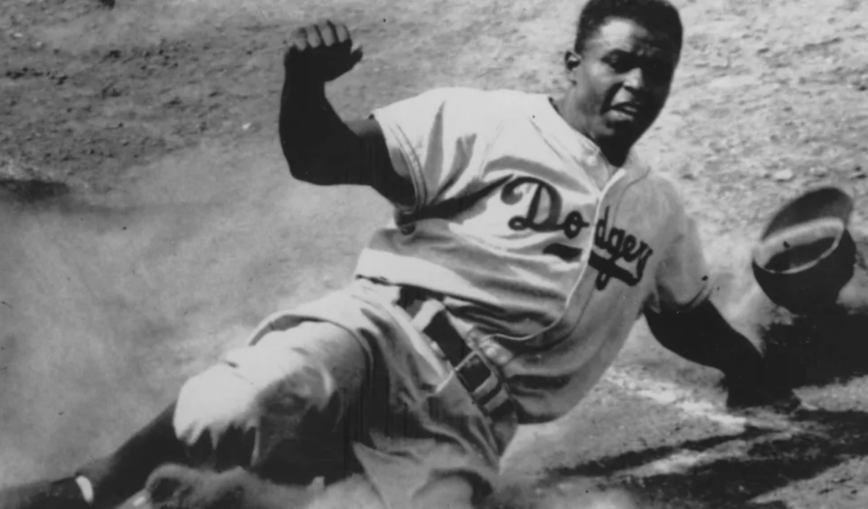

Jones: In the minor leagues things happened. We knew what kind of world we came up in. You can’t prepare for all the things that happen, but Jackie Robinson was a stabilizing force to me because all you had to do was look at what he did. If he could do it, then you can do it. Jackie was all alone and had nobody but Rachel to come home to and vent his frustrations.

There were many times when I came home and I said to my wife, ‘I don’t know how many times I was called a n***** today, but it was a lot. And it’s probably going to be a lot tomorrow.’

Some things you just need to black out. I was threatened and everything else. But it’s a sport. It’s a game and it’s a livelihood. People came to the game because they enjoyed it. You’re going to have haters but sometimes you can win those haters over just by being Cleon and being a good ballplayer and doing your job well.

That’s my mindset, that when someone hollers out of the stands, “N*****, if you hit that ball I’m going to come down there and see about you,” well, I was going to hit that ball so hard that it would’ve gone out of Yellowstone Park. I was going to make sure I hit it hard. That always gave me the power to concentrate on why I was there: to be a ballplayer and to do good. I’d hit the ball of the wall and run the bases and the guy would come down from the stands and say, “By God, n*****, you’re going to be a good one.”

That was who he was but he was telling me who I was at the same time. Negativity has its place, but you have to understand that you can’t stop people from being people, whether they’re black, white, pink, purple, or anything different. You just have to do your thing and you don’t have to win them over, but you can quiet them. You can quiet them down by being the best that you can be.

MMO: Finally, what do you hope readers take away from the book?

Jones: I just hope they take away that family is important, whether it’s your immediate family or your sports family or your neighborhood family. It’s all important and it’s important as you move forward.

My neighborhood made me, I didn’t make my neighborhood. What I got from my neighborhood and all the people that I talk about in the book made for a decent career for me because I didn’t want to let them down. They empowered me to be a major leaguer.

Think positive and be of good cheer, and know that when you work together you can make things happen.

MMO: Thank you very much for some time today, Cleon. Best of luck with the book.

Jones: Thank you.

To purchase a copy of Cleon Jones’ book, click here.