The New York Mets made several shrewd moves in the early-to-mid eighties that aided the club in winning their second World Series championship in franchise history.

From their trade with the St. Louis Cardinals for Keith Hernandez and adding southpaw Sid Fernandez from the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1983, to trading for Ray Knight from the Houston Astros and acquiring Gary Carter from the Montreal Expos in 1984, the team supplemented its young, talented roster with star players and veteran leadership.

But another deal was made in November 1985 that involved eight players between the Mets and Boston Red Sox that would pay huge dividends in the club winning a franchise-best 108 regular season games and being the last team standing at the end of the 1986 season.

Left-handed pitcher Bob Ojeda was the main piece in this mega trade, and played a vital role in both the regular season and postseason in his first year in Queens.

Ojeda, 64, signed with the Red Sox as an undrafted free agent in 1978 and pitched as both a starter and reliever for the major league club from 1980 through 1985.

The Mets were looking to add another left-handed pitcher to their staff for the ’86 season, and the front office zeroed in on Ojeda, whose experience both as a starter and out of the pen made for an attractive option.

What the Mets received from Ojeda in their championship season was more than they could have ever dreamed.

Among Mets pitchers, Ojeda led the staff in wins (18) and WHIP (1.090), while second in ERA (2.57) and fWAR (4.2). He finished fourth in the National League Cy Young voting and tossed a career-high 217.1 innings and an additional 27 in the postseason.

Ojeda came up big when it counted the most, making four postseason starts and posting a combined 2.33 ERA.

After Mike Scott’s brilliant 14-strikeout performance in the Houston Astros’ 1-0 win in Game 1 of the NLCS, Ojeda toed the rubber for Game 2 and tossed a complete game in the Mets’ 5-1 win on the road.

He became the third Mets pitcher in franchise history to toss a complete game in the postseason while allowing no more than one run, joining Tom Seaver (1969) and Jon Matlack (1973).

The lefty was also the starting pitcher in the Mets’ miraculous comeback victory in Game 6 of the World Series against his former club. He tossed six innings of two-run ball, and didn’t allow the Red Sox to score after the second inning.

What’s incredible to remember is that Ojeda was this effective while dealing with a severely injured elbow. Ever the gamer, Ojeda had to navigate pitching through pain and whether that would ultimately lead to ineffectiveness and potential long-term injury.

In total, Ojeda spent five seasons in Queens, posting a 51-40 record with a 3.12 ERA in 140 games (109 starts). Among 42 pitchers with a minimum 500 innings pitched with the Mets, Ojeda ranks 9th in ERA and WHIP (1.182).

Following his playing career, Ojeda rejoined the Mets as a minor league pitching coach for several seasons, and later joined SNY as a studio analyst and spent six seasons in that role.

I had the privilege of speaking with Ojeda where he discussed going undrafted, how he dealt with injuries and the championship season of 1986.

MMO: Who were some of your favorite players growing up?

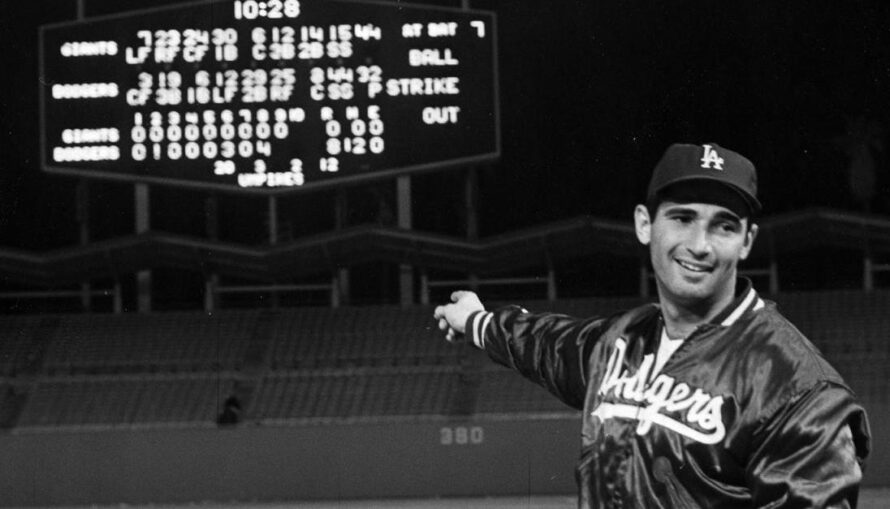

Ojeda: I was born in L.A. and grew up there, and Sandy Koufax was my guy.

As a kid, I didn’t watch a lot of sports; I was too active and hyper. I could watch a couple of innings of a baseball game or a few minutes of a football game and then I was out the door to go play.

MMO: At what point during your development did you start focusing primarily on pitching?

Ojeda: I didn’t really grow up honing in on pitching, and that’s an honest and straightforward question.

What happened to me was I didn’t get drafted. I only went to junior college and was good, but I did not get drafted. I signed after the draft for $500, which wasn’t a lot of money then either. [Laughs.]

I went all in. I was like, I got an opportunity and I’m going to try my best. I showed up at Elmira and my first manager was Dick Berardino, and this is a message to all these kids out here who hone in on pitching when they’re four years old, and that is do not do that. Mom and dad, don’t do that to your children.

I showed up at the field and introduced myself to Dick. He said, “What do you do?” I said, ‘Skip, what’s the quickest way to the big leagues?’ He said, “Pitching.” I said, ‘Well, I’m a pitcher.’

Up until then I hit and pitched, and most guys that sign are very athletic and very talented; not only in different sports but different positions. And I was the same. But I did not zero in on pitching until after I signed.

MMO: You mentioned signing as an undrafted free agent with the Red Sox. How did that come about?

Ojeda: A good friend of my father’s, a fellow from the little town I was from, he was this classic old dude. He always had a cigar in his mouth. He became a bird dog scout, and that’s a scout who is not really affiliated, but he knew people with the Red Sox.

Once I didn’t get drafted, he came up to me and my dad at my dad’s shop and said, “Look, I can get you $500, and you can sign with the Red Sox. That’s the best I can do.”

Even then I was a little nervy and I said, ‘How about $750?’ He said, “Nope, $500 that’s it. Take it or leave it.”

I took it and that’s how my time with the Red Sox began. He was just a bird dog in town, real nice old man and he’s since passed away. But he’s the one that got me started in professional baseball.

MMO: In a New York Times article you wrote back in 2012, you described how you essentially always pitched in pain, even as a kid. Even through all the pain, you put together a quality career. How were you able to navigate and circumvent the pain throughout the course of your career?

Ojeda: A lot of these guys that we watch on television and are fans of, you don’t know what they go through to get on and stay on the field. A lot of people do that and that’s the type of thing that I didn’t admit to myself when I was going through it, as with guys today. There are guys who play with pain, I am not the lone ranger by any stretch.

The crux of it is when pain transfers over to glaring injury. That’s the fine line and how far do you want to push yourself in your particular circumstance to push through.

A lot of guys pitch in pain but when you’ve already been diagnosed with an injury, and yet, continue to go through it, that’s the part I think is very individualistic. And there’s no right or wrong. It’s just what you can live with.

Now I sit around and am older, and I still do things in the game, but I look back and I would not have missed the ’86 playoffs or World Series for anything in the world. Sitting here today, had I chosen to sit out would’ve been very difficult to live with.

You get one chance if you’re fortunate, and if you’re really fortunate you get several chances to go all the way in any particular sport. To sit on the sidelines with something where it’s like, can I actually do this? Potentially hurt myself long-term but I don’t want to miss it and I’m still effective, that’s an individual choice. That’s something that each guy has to navigate.

MMO: It’s interesting how you mentioned how so many players are dealing with nagging pains and sorenesses, and how fans don’t know what goes on behind the scenes. When I interviewed Trevor May while he was on the IL, he talked about toeing the line between playing through soreness and taking a needed rest when it was something more than that.

Ojeda: In my particular case, I had already been diagnosed with a severely injured elbow. The diagnosis was in and there was no more question about if it’s this or that. I was diagnosed with a frayed ulnar nerve and chips underneath the ulnar nerve and in the groove that was causing my arm to literally lock in place while I’d be warming up for a game.

That just becomes, I’m a rock head but I don’t want to miss this. I have no regrets.

MMO: When were you diagnosed with a frayed ulnar nerve?

Ojeda: In ’86. The second half of the season, I was struggling pretty much most of the season, but it was like, okay, we all pitch in pain. Nobody plays 100%.

But it kept deteriorating and I reached a point where I was taking anti-inflammatories and getting shots to get through it. I had the x-rays that confirmed there was an injury; it was a drastic elbow injury. I chose to continue because I was still effective.

My doctor, he’s passed away, Dr. Parkes, allowed me to do that. I told him, ‘Doc, if you say this happened, this conversation, I’m going to tell everybody that it never happened. And that you’re not telling the truth.’ [Laughs.] And for some reason he believed me.

My trainer, Steve Garland, knew the truth, and yet, allowed me to continue. Why? Because it was my choice and my responsibility to accept the consequences of going forward with an injury, not pain, an injury.

I thank them every time I think about it that they let me do it.

MMO: In that same New York Times piece, two names that stuck out to me in terms of your development were Mike Roarke and Johnny Podres. Can you talk about what each of them meant for you?

Ojeda: I met the Pod in fall ball in 1978 with the Red Sox. He was awesome and a legend. He was this big, old boiler, and was chain-smoking like a maniac. I loved the guy. He was just no-nonsense and would give it to you straight. He taught me my changeup and curve.

That was instrumental in me moving forward because I had just come off a 1-6 [season] in Elmira, and then I went down after the season to Sarasota. I learned the changeup and learned the curve, came back the following year and then I was 15-7 with a 2.43 [ERA], and that was largely because of Johnny Podres.

Mike Roarke, I had him in the big leagues. Mike was the kindest gentleman you ever met. The kindest guys are usually the toughest ones, and Mike was a tough guy. But he was so kind.

My father pretty much taught me everything, but Mike Roarke taught me the professional angle of pitching. I learned immensely the difference between the minor leagues, college and professional [level], when it’s a job. Mike was instrumental in that.

He was one of the finest gentlemen I ever met and very knowledgeable in the game.

MMO: Did you already have a changeup and curveball in your arsenal and Podres tinkered with your grips, or did he introduce those pitches to you?

Ojeda: Good question, he messed with my grip a little bit. My father did not let me throw a curveball until I was seventeen. My father was ahead of his time, I don’t know how he did it.

He was a big man at six-four, pitched in the army and knew the dangers of pitching because his shoulder blew out and that pretty much ended his career.

He did not allow me to throw a curveball, so I had no idea how to throw a curve. The Pod got a hold of me, and I think I just turned 20 when I went down, and he showed me the grip of the curve and a different grip on the changeup.

I had messed around with a changeup in high school and junior college, but I didn’t need it because I threw really hard. I was a one-trick pony.

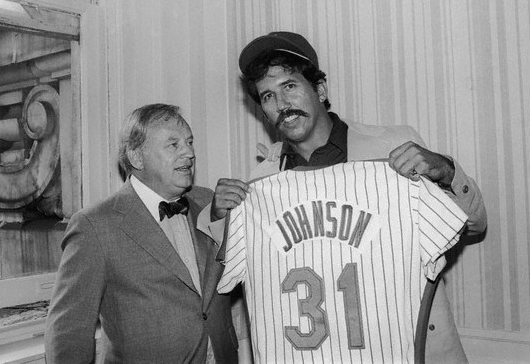

MMO: What were your initial reactions on getting traded to the Mets in November 1985?

Ojeda: I was thrilled because Boston at the time was a train wreck. Ownership was in turmoil, the organization was turning over from veterans to bringing up younger guys and there was a lot of animosity in that locker room. That’s one of the most important things that I did as a coach is that you don’t have to love everybody but there was a lot of animosities and a lot of anger that the old guys were getting pushed out and the young guys were coming in.

To get out of that environment with kind of a bunch of stale, old, crusty guys and come over to New York, well, I sat there for two weeks in spring training and didn’t say anything, I just watched these guys. I felt like I was in a room full of puppies!

At that time, I was a five-year veteran, so I’d been around a little bit. I was a little jaded because I was around all these grumpy, old dudes. I just embraced it. I embraced their youthful exuberance and sort of their blind excitedness of what’s possible. When you’re young you’re invincible, and I was like, Yeah, this is what I’m talking about.

Did everybody love each other? No. But there was a common goal, and that was to win every day starting at 7:05. And that was so refreshing to come into, especially as a veteran.

MMO: Did you have any idea of how special this ’86 club could be when you arrived?

Ojeda: Not a clue. I’m in my own world and especially back in the day, I paid attention to what I was doing and what was happening in the American League; I could care less what was going on in the other league. I had my hands full doing my job, so I did not know one thing about the Mets.

I probably did a little reading once I was traded over but you don’t really know exactly what it is until you get there. You’re reading stories that are interpreted from people who do their best to project a picture. But once I got in that locker room and sat there, honest to goodness, for two weeks and didn’t say a word and was just looking around and taking it in, I was like, Okay, I get it now. These guys are fired up.

Davey [Johnson] certainly sent the message out that we’re winning it all this year. That goal of winning it all was so important; that’s the only time I ever felt that. The only time in my entire career that I ever felt that.

It wasn’t like we were going to win the first ten or have the best pitching staff, the best defense, hit the most triples; none of that nonsense. You know what boys? We’re going to win the most games and we’re going to win the World Series. Not our division; not this or that. We’re going to win the World Series. Anything short of that is a bust, and I think that helped propel our mentality.

That’s why we were like we were. They say we had a little panache, if you will, and we did and that’s because you have to. But you also have to have the horses, and this ball club was pretty good in ’85, and we just took it over the top in ’86.

MMO: Was there any pressure on not only joining a new team, but a new league when you came to New York?

Ojeda: No. I always put pressure on myself but I didn’t add to it.

I didn’t get to start the year in the rotation, I started in the bullpen. Early in the season they scheduled a lot of off days, and Davey said, “You’re a starter and you’re starting for me. We need you and that left side, especially going against St. Louis. But I have to start you in the bullpen.” I told him that was fine and it’s not about me, it’s about my team, my new team.

I actually started four or five less games than everybody else, but I wasn’t complaining. I was just glad to be in the big leagues, glad to be with an exciting team and winning ballgames like we were eating potato chips, it was nuts!

MMO: What are your memories from your Game 2 start in the NLCS against the Houston Astros?

Ojeda: The season doesn’t start until the playoffs. I know it’s cliché, but it’s true. As you’re playing a season, early in the season there’s a degree of pressure; the middle of the season there’s a degree of pressure; and the end of season until you clinch the playoffs there’s a degree of pressure. You take a nice breath after you clinch, but then it starts all over. Then all of a sudden, it’s intense.

If you go to the playoffs, the season does not start until you’ve reached the playoffs. That’s the goal and mindset you need to have. I don’t care how good of an April or August or September we had, until you get to the postseason it becomes real.

When I started that game, it’s a sense of all or nothing. There’s no tomorrow. Each individual game is in and of itself a standalone. I’m not thinking about tomorrow, I’m not thinking about yesterday, I’m not thinking about last week, I’m thinking about today.

The pressure in your head and the pressure of the game is vital to have that attitude that it’s just a game, a huge game, but it’s one game. It’s one out at a time. I know these are clichés but they’re very, very true and that’s what I drew on when I got to go through it.

MMO: So, you would use those mantras to help keep your mental game in check?

Ojeda: Yes, absolutely. You have to put yourself in a mental place where you can function. And that’s individual.

I was one of those people that liked to play for keeps when we used to pitch quarters and play marbles and all these old people games. We were doing it for fun but I wanted to win. As soon as the bell rang, okay, this is for keeps. I tended to embrace that.

I always did embrace pressure, I embraced it and liked it. I used the pressure to help me rather than defeat me. But you have to manage it and you have to manage it to where you can function. It’s not something that happens by accident and there are people who, no question, fold under pressure.

You’re either a pressure folder or a pressure player. You do it 100 times and you will be a folder each one of those times, and if you’re a pressure player, you’re going to come through in the time in large part.

There are existential reasons why failure and success happen, but there are people who are chokers and who do not like pressure. And that’s life. I’m not slamming them, that’s just life.

Pitching is individualistic, too, because I’m the guy on the bump, I’m in charge of everything. I promise you there are guys who will pitch a beautiful game and will lose 1-0, 2-1, 2-0. They’ll pitch a beautiful game and afterwards talk about how it was tough luck and know they threw a great game. There are guys who embrace that.

I wanted to be the guy and thrived on being the guy who wins 1-0; who wins 2-1. And it does not feel the same. I promise you, when you’re on the mound, it is not the same because people get exposed when they get a lead. There are guys, you can check with stats, who get a lead and they’ll give it right back and then settle in. They’re comfortable being good enough to lose. Those are the guys you have to weed out to be a championship club.

MMO: You then started Game 6 of the NLCS, and after giving up three runs in the first inning, you buckled down and threw four scoreless innings after. Even though you guys had a 3-2 lead in the series, it seemed like that game was treated as a must-win, given that Mike Scott was looming for a Game 7. What stands out to you about that game and start?

Ojeda: That was the game where I just had three shots in my elbow two days before. No one knew. Dr. Parkes did it for me; I flew down to Washington and got the shots and flew back. He was awesome.

When I was warming up for that game, I felt like I had sandbags in my elbow. I just could not get loose.

I remember the great Mel Stottlemyre was looking at me like, wow, this really doesn’t look good. He didn’t want to say that, so he said, “How are you feeling? You feeling okay?” I told him, ‘No, I’m good, Mel. [I] just have a little trouble getting loose, but I’m good. I’ll be all right.’ [Laughs.]

I went out there for the first inning and was like, Oh, my god, how the hell am I going to get through this thing?

Fortunately, I got through that first inning and things loosened up and I was able to give them a few more innings to help us get that win. That was all shot related because it helped with the pain, but it clogged up the elbow a little bit.

MMO: Was there pain pitching in your two World Series starts?

Ojeda: You couldn’t focus on it. The pain was still there, and like I said, I’m not the lone ranger. But I had an injury and I chose to go forward with it. When you make that decision you can’t start crying about it, you have to roll with it.

That game in Houston was the most uncomfortable game I had thrown. Game six was pretty uncomfortable as well, but at that point once we got to the World Series, there are no more shots, no more anything. I just loaded up on pills and was going to do the best I could. I didn’t want to quit on my teammates.

I was still effective even with the injury, but I didn’t want to give up on my teammates and I said let’s just go with this thing. If it ends your career, so what? I got to the World Series because inside me was a 12-year-old little boy who dreamed about this day. I wasn’t going to miss it.

MMO: Following your playing career, you took some time off before returning as a minor league pitching coach in the organization, and then took some more time before signing on as a commentator for SNY in 2009. What prompted you to come back to the game in a broadcasting capacity?

Ojeda: Very simply, they asked me. I know the Wilpons draw emotion from the fans, which is fine. But they treated me fantastic. They really did. I can’t speak for anyone else, but they treated me great. They actually came to me and said, “We want you back in the organization.”

I coached for those three years and I told myself I was going to take a break. And then I went back to Shea Stadium for Shea Goodbye, as a matter of fact, and they told me they liked to have me back. They asked me what I’d like to do, would I want to coach again, do this, that or the other. I said, ‘I’m thankful you’re having me back because I do love the Mets and I do love baseball. So whatever you think.’

The great Curt Gowdy Jr. called me up and said, “Look, I’m not giving up this job. You have to audition.” I auditioned for Curt, and they liked what they saw and then I rolled into that. But I never, ever had any ambitions to do television work because it wasn’t my thing or ambition or goal.

I loved every second of it. They were great to me. They let me be honest and I always tried to be fair. It wasn’t just getting the microphone and talk smack. I didn’t want to do that because I grew up with that as a player. I’d be like, that ain’t cool, I wish that guy would say that to my face. They get on TV and all of a sudden they’re talking all of this smack, so I said no.

I always did it like I was talking to a guy when I was doing a show. I’m looking at the camera and if I’m saying something about a particular guy I’m saying it to his face, because that helps govern what you say. All of a sudden, you’re not such a big shot when you’re talking to the guy.

I was on the backside of that where I’m watching an interview on TV or listening on the radio and I’m thinking, boy, this guy sounds like a different guy when he’s in the locker room. I didn’t want to be that guy, and that helped me do my job which I loved doing.

MMO: I loved the work you did on SNY. I think many Met fans respected you for your frank and honest analysis, and the fact that you always came prepared during good times and bad.

Ojeda: Thank you very much, that is a great compliment. I didn’t want to phone it in for you guys because I’m a Met fan myself. I just wanted to be honest. And the one thing with you guys is you’re so well-informed. I’m not going to sit there on television and tell you 1+1=7, where you guys will say, wait, 1+1=2. What’s this guy talking about?

I wanted to come at you honestly and show that I did my research, did my homework, and I didn’t just throw out numbers. I used to be with the guys at the studio, and they were such a huge help, and we’d spend hours researching making sure that something I was going to say was true, honest and backed up by numbers.

I was very emotional, and still am, because I have feelings and it matters to me, but it’s based in truth and reality that someone can check. I may have gotten a little hot because it’s an emotional game and I’m an emotional person, but it was always honest, and I loved doing it. I wouldn’t mind doing it again.

MMO: I was going to ask you if you had any desire to get back in the game in a broadcasting/coaching/front office advisory role?

Ojeda: Yes. I had to take a breather because that’s the way I am. So, I’ve taken a breather and recharged my batteries. I’ve never liked doing anything half-way. If I’m going to be a baseball player, I’m going to be a baseball player. If I’m going to be a coach, I’m going to be a coach. If I’m going to be on TV and be an analyst, I’m going to give it my all.

I’m at a point now where I feel great. So, to come back in one of those capacities would be great for two reasons. One, I love baseball, I always have and most of us do. And two, I really enjoy the Mets and I enjoy the Met fan.

What’s amazing to me is the Mets are the organization, the players come and go, that’s just life. The players come and go, but you stay a Met fan. As a Met fan, I can’t be traded to the Dodgers, I’m a Met fan, that’s it, that’s my team!

I have that affiliation and to do any of those above things with another organization is not that appealing, and I probably wouldn’t do it. But to do it for the Mets. Like I said, we don’t have the luxury of being traded; our feelings and allegiance are sort of locked in. And that’s what I admire about Met fans.

The vast majority of Met fans are true and blue and do not give up on their team. Sure, they take a lot of stuff for not winning much in the recent years, but they never quit on you. And that’s the way I feel. I don’t quit on myself, Met fans don’t quit on their team and we’re in it together. It’s a great feeling to have that connection and it can’t be broken.

MMO: What was it like coming back for Old Timers’ Day this year?

Ojeda: Fantastic! I have been around the ballpark a lot as a player, coach and on TV, but they treated 65 guys as if we were going in the lineup that night. It was incredible.

They just made us feel so welcome, I can’t say enough about the new ownership. It’s coming from the top down too; I will tell you that right now. That’s coming from the top. He (Steve Cohen) set a tone and a precedent, and it was evident like I have never seen since I last put on the uniform as a player there.

Like I said, they treated me great for years and I have no axe to grind. I’ve been very, very fortunate with the organization. But everybody who was in that uniform and had some gray hair and a little limp, and even some of these younger guys who aren’t that far removed from playing, were made to feel so warmly welcome. It’s like, you are part of this, it’s like the cliché of a family, I’m not going to go that far but we were made to feel incredibly welcome.

It was so refreshing and that breath of fresh air that breathed life into that stadium and the stadium even felt alive, it was beautiful. There was a beautiful moment that I thoroughly enjoyed, and I know a lot of my teammates and guys I just met loved it.

They all walked out of there feeling ten feet tall. It was amazingly done for these old guys. It was awesome.

Follow Bobby Ojeda on Twitter, @BobOjeda19