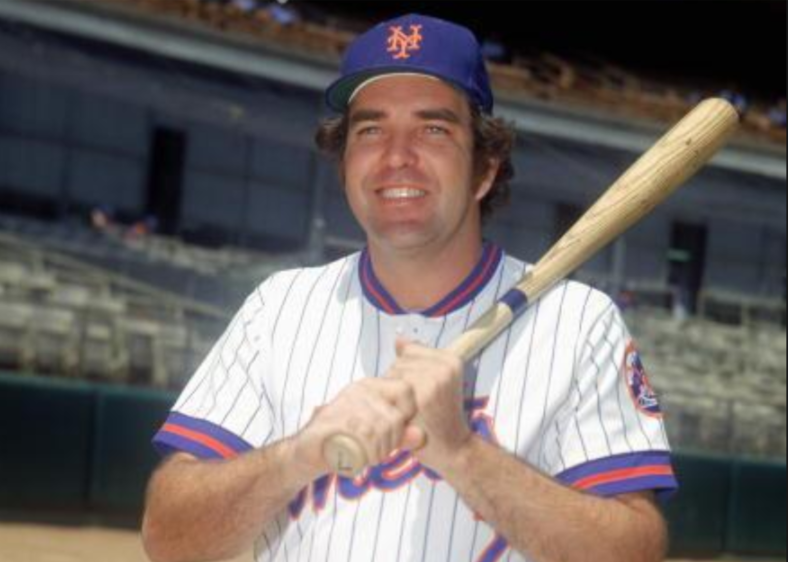

Growing up in Bronx in the 1940s and ’50s, Ed Kranepool spent much of his time playing stickball in local parks.

In fact, stickball brought refuge to a young Kranepool. As his stickball reputation grew, local gangs treated Kranepool well and insisted he not hang around with them after dark as they didn’t want him to get into trouble and not be able to play on their teams.

Growing up in a single-parent household, Kranepool was drawn to athletics, mainly basketball and baseball. With the guidance and support of his next door neighbor, Jimmy Schiafo, who acted as a father figure, the left-handed hitter was developing and drawing interest from Major League teams.

The team that showed the most interest in Kranepool’s services was that of the recently-formed New York Mets.

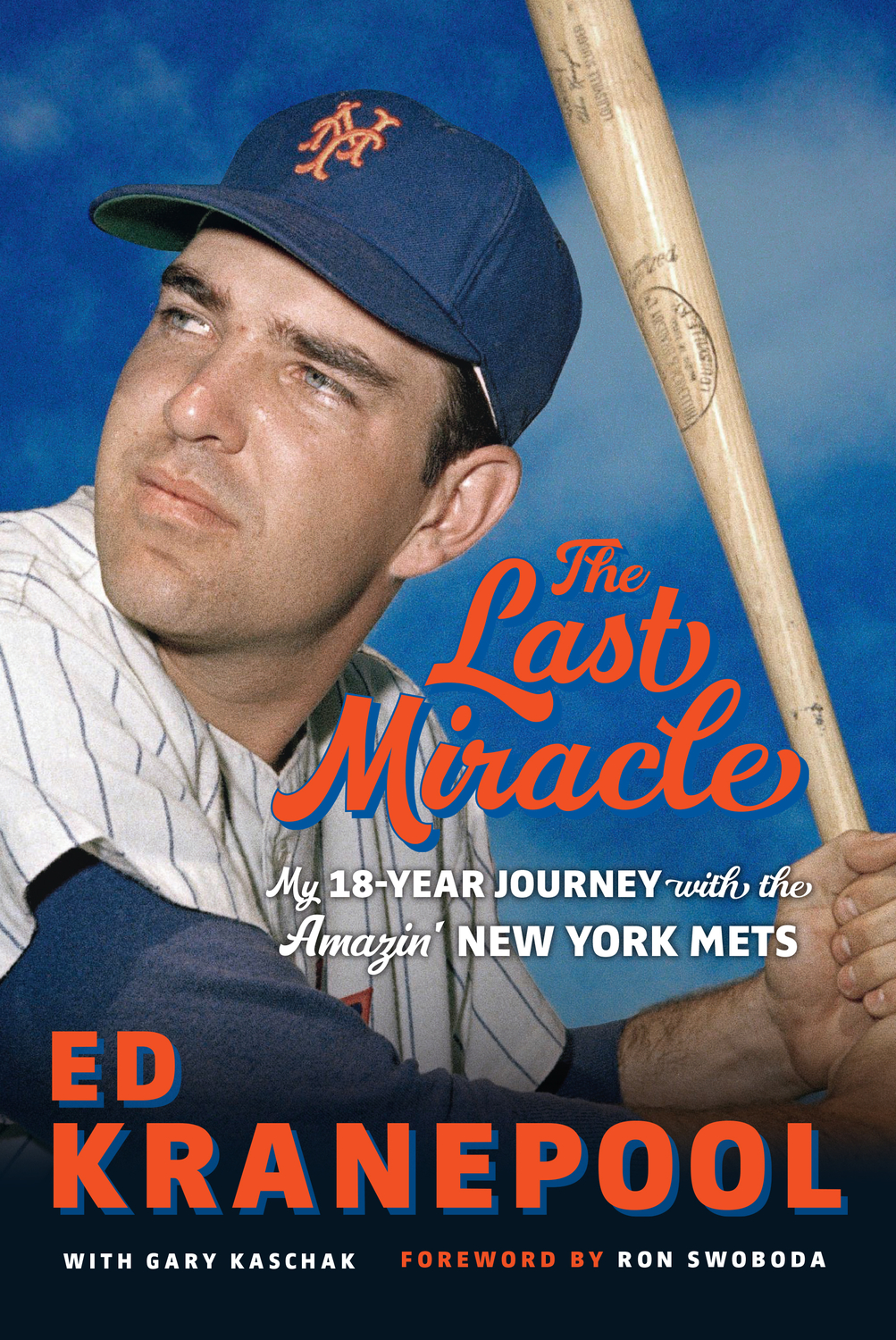

Sixty-one years after a then 17-year-old Kranepool signed a contract with the Mets, the Bronx-native has recently penned an autobiography on his life and playing career called “The Last Miracle: My 18-Year Journey with Amazin’ New York Mets.”

The memoir, published by Triumph Books, focuses on Kranepool’s development as a player, memories of the club’s first World Series championship in 1969, organizational miscues and his life-saving kidney transplant.

Triumph Books

Kranepool, 78, offers frank and transparent views on a myriad of topics, including his displeasure of Yogi Berra’s managerial decisions, resentment toward Gene Mauch for not playing him in his only All-Star Game appearance in 1965 and frustration with many of the Mets’ front office moves in the mid-to-late 1970s.

Over his eighteen-year career, Kranepool played for just one organization, a rarity in today’s game. Kranepool is the franchise leader in games played (1,853), owns the third-most hits (1,418) and fifth-most RBIs (614). ‘The Krane’ also owns the eighth-most home runs by a player under the age of 20 in Major League Baseball history with 12.

In the latter part of Kranepool’s career, he developed into a dependable bat off the bench. In 1974, Kranepool went 17-for-35 (.486) in pinch-hitting opportunities, setting a single-season record for highest batting average by a pinch hitter.

I had the privilege of speaking with Kranepool over the phone, where he discussed his early development in the Bronx, spending nearly two decades with the Mets and his kidney transplant.

MMO: What prompted you to write the memoir?

Kranepool: I just figured I had a lot of stories to tell. Ralph Kiner is not around, so why not let the fans enjoy them? I participated in all of them since 1962, and there’s nobody here to talk about that stuff.

MMO: A prominent figure throughout your youth was your neighbor, Jimmy Schiafo. You write in the book that he acted as a father figure. How important was his presence in your life and early development as an athlete?

Kranepool: I was brought up without a dad; I lost my father in the war. I needed a replacement and he was my next-door neighbor and took a liking to me.

He had two boys and they were involved in baseball, and one was on my team. He worked us all out and kept us in shape and taught us the fundamentals of baseball. That’s really where I got my start.

MMO: You write that your reputation for baseball started by playing stickball in the Bronx. What memories do you have from playing stickball?

Kranepool: Stickball was the game to play in the Bronx because you had a lot of playgrounds with concrete fields; you didn’t have a lot of playing fields that were being taken care of. We played every day.

Being a guy from the Bronx, we didn’t have a lot of money in our pockets, so we were going out to camps and stuff like that in the summer. We all got together at the playgrounds and worked out every day. We ran there after breakfast and stayed there until lunch. We then ran home to grab a sandwich and came back and played basketball or baseball or whatever you could do on the playground.

It was cheap, inexpensive and a lot of fun for all of us.

MMO: Your first significant injury was when you fractured your elbow on your throwing arm in your second year of Little League. You write that your elbow never healed and you never had surgery to repair it. Did that injury ever bother you later in your career? And do you think you would’ve kept pitching?

Kranepool: I think I could have pitched. I was an outstanding pitcher in Little League and set all kinds of records. I was never the same afterwards and nobody really knew about it. That’s something you don’t brag about with any type of deficiency you might have. So I played with it.

Did it affect me? It probably did, it probably affected my swing. I was a better player, I think, before that [injury]. But you still play and overcome and enjoy the game of baseball. I played every day and was able to perform and we enjoyed ourselves.

To this day, it’s not right and never will be.

MMO: Is it true that you taught yourself to throw right handed after that injury?

Kranepool: I did! I caught for a year and a half and I can throw right handed. I’m not as good right handed as I am left handed because I never continued it. But I could throw because I wanted to hit. Certain things you can’t do so you just overcome them and keep trying.

MMO: That reminds me of Billy Wagner learning to throw left handed after breaking his right arm when he was a kid.

Kranepool: Well, that’s what it is. You use the other one and compensate for that. If you keep throwing with the opposite arm you’re going to overcome everything.

I did it for a year and a half and I had fun doing it. I liked catching because you’re in the action.

MMO: Can you talk about the interest that the New York Mets showed in you throughout your high school career, and the relationship you developed with scout Bubber Jonnard?

Kranepool: Bubber was the scout in the tri-state area, and he followed all the players as they were growing up. When I was in sandlot baseball, I attracted a lot of attention because I was a pretty good hitter, and pitched a little bit but could never throw the same [after injury].

I really attracted the Mets because of my hitting. They followed me during high school and went to all my games.

When I signed, I graduated high school and two days later the Mets came to my door, sat on my doorsteps and wanted to talk a contract because you can’t sign until you’re graduating class is out. They were the first ones in my house and they sat there all night, and we finally signed a contract.

MMO: I still can’t wrap my head around the fact that you graduated high school, signed a major league contract and then took a plane to the West Coast to meet the Mets just a few days later. Do you remember what was going through your mind at the time as a 17-year-old?

Kranepool: It was excitement for myself signing a contract. It was my goal as a Little Leaguer to start and play in the major leagues and perform. I didn’t expect to go out to the National League and to Los Angeles straight away, but I did.

They packed me up and put me on a plane; the first time I ever flew. Little did I know that opening night out there was Sandy Koufax. He pitched a no-hitter and struck out 13. I told Casey [Stengel], ‘I’m ready for college.’ [Laughs.]

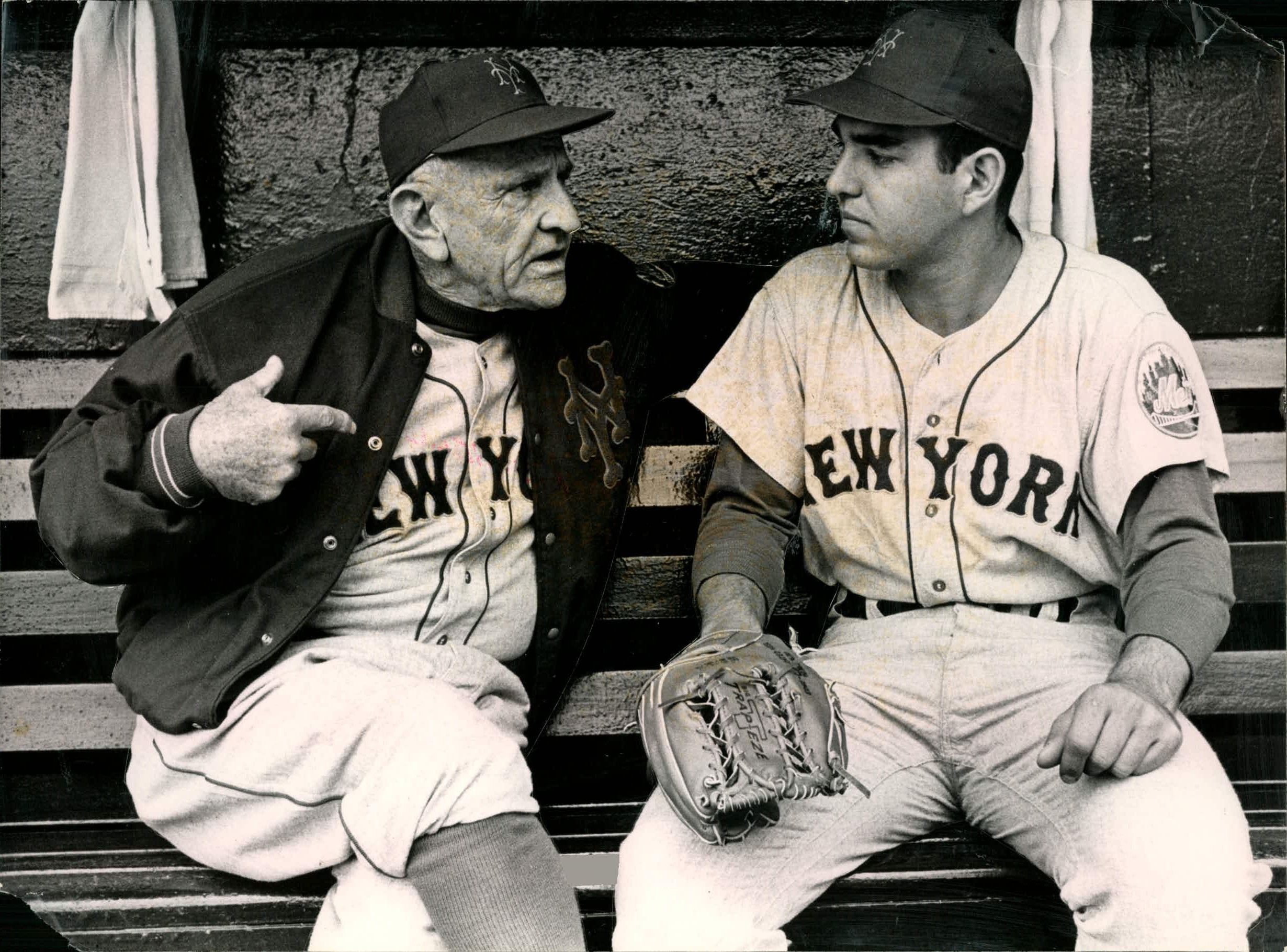

MMO: You sat next to Casey Stengel during games to observe what was happening and get a feel for the major leagues when you arrived. What were some of your early takeaways from sitting next to Stengel?

Kranepool: He was having a good time with himself. He was 71, enjoying baseball, loving life and always discussing the game. He was the first one at the ballpark and the last one to leave.

He put a lot of time in on the team but we just didn’t have the talent. We had a lot of older guys who were past their prime. Back in those days, 35 was more than your prime, and he knew that he really didn’t have the talent to really perform against the other teams.

Stengel took a lot of pressure off of guys because he kept the press busy writing stories about the Mets, talking about the old Yankees, all kinds of things. It made it easier for the players to perform because losing 100 games was not easy for any team. It’s tough to lose 100 games, and we did it for several years.

MMO: Obviously, the first seven years of the club’s existence were disappointing and underwhelming. And then came 1969. When did you start to notice that things were changing for the better in the organization?

Kranepool: We made a lot of changes in the front office, and of course, we acquired Gil Hodges in 1968. He was a young manager coming over from Washington, and he taught us how to play the game and how to win.

We were better in ’68. I think it was the second time we hadn’t lost 100 games and we thought it was a big improvement. In spring training, he discussed it with us and told us to set some goals for ourselves and taught us how to win, how to play the game and how you should play. A win here or there makes a big difference at the end of a season. So we did perform better.

By the summer of ’69, we started to get to .500. When we got to .500, it was at the stage of the season where we had never been that high in the season.

We started to play really good baseball and in the second half of the season we won 60-to-70 percent of our games. We beat every club that we had to and went on to win the pennant. We beat the Cubs by eight or nine games, and they were up eight or nine games most of the year.

MMO: Something you write about in the book is that you wish the club gave you more time to develop, especially when it came to the mental preparation of the game. Looking back, how would you have handled a young Ed Kranepool?

Kranepool: You can’t handle that any differently, they’re in control of your outcome. I would have been better off playing in the minor leagues for a year or two developing with guys my own age, this way you can perform up to what your ability is.

Every time I went to the minors, I hit over .300 and was one of the outstanding players in the league. I just never developed.

You don’t improve facing Koufax, [Bob] Gibson, [Don] Drysdale, [Juan] Marichal and all of these Hall of Famers. There were so many of them in the National League in the sixties, and you if you look at the records most of those guys made the Hall of Fame. Guys don’t really perform and improve against those types of pitchers.

MMO: Did you feel pressure to succeed right away given all the hype and publicity surrounding your signing?

Kranepool: I did because everyone expected a whole lot more from you. They wanted you to do more because they wanted you to lead them to the pennant. And that’s why they were frustrated: they wanted to win. I don’t blame them, I wanted to win!

Until they surrounded me in the lineup, they could always pitch against you. I was an aggressive hitter and I wanted to swing. I wasn’t going to walk my way to the major leagues. I would swing at pitches that were out of my strike zone, out of my hitting zone and I didn’t perform with it.

As I matured and got older and caught up with the league, I started to produce some numbers that the Mets were expecting. But I’d been around so long that the organization said, “Maybe he’s over the hill.”

I was in the league for 17 years and performing. I could have done a lot better late in my career; I hit .300, .320, .290, .280. Those are competitive numbers to the better players in the league. But people still remember that you struggled when you were 17-18 [years old] in the league.

MMO: You were a terrific pinch hitter, as you posted a career .277 batting average in those situations. Can you talk about some of the challenges of pinch-hitting, and the preparation it takes in order to come up late in a game?

Kranepool: Mentally, I wanted to prove the manager wrong. When I wasn’t playing, I should have been playing. They should have had me in the lineup so I would get four at-bats instead of one.

Once I had that job, I prepared myself and in the middle innings took some extra swings down below in the dugout and got myself ready and had my bat prepared. I knew when I was going to pinch hit; I didn’t pinch hit when the game was not on the line. It was always in a crucial situation where the game was on the line and I knew who was going to pitch, so I was physically ready to pinch hit.

As I got older, I did it so well that I was efficient in it. A team like the Mets, when they’re not playing well, you don’t have that many opportunities for game situations. You’re not going to pinch hit when you’re down 6-0 and you have a couple other options to choose. They’re going to use them and I never got a chance to play in a lot of games.

It was a situation where I was doing it to show up the manager and work my way back into the lineup. But I did it pretty well.

MMO: From reading your book, you can tell how much respect and appreciation you had for Gil Hodges. From everything I’ve read about Hodges, he really seemed like a manager who was ahead of his time with his methods and how he managed a ball club. In your view, what did Hodges do well as a manager?

Kranepool: Gil learned how to use everybody and had one set of rules. He was a very tough disciplinarian. I had trouble with Gil in the early years, I had some disagreements with him and we didn’t get along for two or three years. But I fought through it and he did also.

He worked with me and sent me out to show me that he was in charge, and I went down to the minor leagues and hit over .300 and worked my way back to the majors. M. Donald Grant gave his word that he would get me back to the majors and wouldn’t just strand me in the minors. When I performed, he lived up to his promise and I got along very well with Mr. Grant.

MMO: I loved the anecdote you shared about winning a Kobe bull while barnstorming with the Mets in Japan in 1974. Can you talk about that event, and how you ended up with a bull as a prize?

Kranepool: I won a bull in Japan because I was the best hitter on the ball club. I led the team in home runs and average and played well over there and got an award.

It was quite funny how I ended it in the last game of the year. It was either myself or the first baseman the Giants had, Sadaharu Oh. We had a couple of home runs a piece, and then I hit a home run in the first inning. They moved the bull to one side of the field, and it looked like I was going to get it. Then Oh hit a home run, and they moved the bull back to the third base-side. Towards the seventh or eighth inning, I hit another home run, so I won the bull. I hit about eight home runs in 18 games.

They gave me the award and it was fun. I didn’t bring it home because it was too expensive; you had to leave it in quarantine for a while. I traded him for a couple of first-class tickets to New York and left the ball club with a week to go. We had a full week left, but I didn’t choose to stay in Japan.

MMO: You’re very honest and transparent throughout the book, especially with certain individuals like Gene Mauch, Yogi Berra, Joe McDonald and Joe Torre. Can you talk about your openness with some of the displeasure you had for certain individuals?

Kranepool: Whoever’s in charge, if they don’t treat you right, you’re going to treat them the same way they treated you. They didn’t make considerations and didn’t keep their promises, so there’s no way you’re going to like them.

Gene Mauch was a tough manager to play against. He always wanted to win and do anything to win for his ball club, had nothing to do with me but he was tough on us. You wanted to beat him and every time we played you performed a little bit better.

Some of our people were incompetent in our organization. They made deals and trades and got rid of players who should’ve been playing, and other guys they kept. I wanted to win as a young player coming up, I was tired of losing. When they kept making bad moves, I critiqued them and let them know that I didn’t like it.

The only thing I wanted to do was win and win a World Series, and win a couple of them. We should’ve won two, we only won one. We lost the second one and that was incompetence on the manager’s part. We should’ve been a better ball club then we were. If Gil was alive, we win more pennants and become better for it.

MMO: One of the many things I learned while reading your book was that you were offered the opportunity to work with Robert Redford for “The Natural.” Can you talk about that?

Kranepool: We did. A lot of guys got opportunities when they were performing there. You had to play and do it in Buffalo. I didn’t choose to go up there because I didn’t know how long I was going to be at minimal pay.

Robert Redford was the star and we had to teach him how to play baseball, and we worked a little bit with him in New York. But we weren’t going up to Buffalo. I wasn’t going to spend time up there without my family.

MMO: You write about your desire to work in the front office for the Mets after your playing career was through. Was that something you had given a lot of thought to?

Kranepool: I always did. I never wanted to manage, I didn’t want to confront the players on a daily basis; let them perform and do it on the field. I can work from above and around them and that’s what I wanted to do.

I probably would have done it if Mrs. Payson stayed alive and didn’t give the club to her daughter and pick Joe McDonald to be the general manager. He killed off some minor league teams, traded those players, and then he traded from the major league club and the Mets went from first to last.

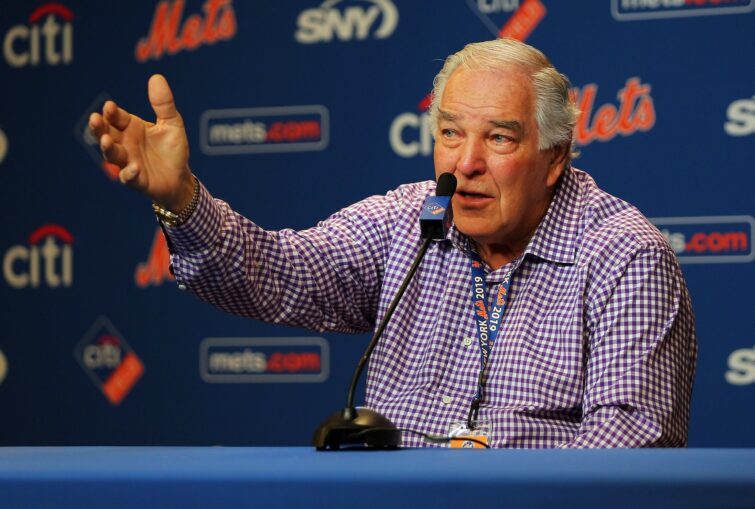

MMO: You write about the process it took for you to find a kidney donor, and the help that Jay Horwitz provided to spread the word. Several years removed from surgery, how are you feeling?

Kranepool: I’m doing great! It’s four years since the surgery and it’s acting well. It did take me a couple of years to do it, and then we finally got one (kidney donor).

We were very lucky to be able to put together a structure, a deal that helped two guys; myself and another gentleman who was a firefighter. He actually got my donor and I got his wife as a donor; she was a perfect match. It worked out well for both.

MMO: When you look back on your career, Ed, what are you most proud of?

Kranepool: I’m proud of staying long enough in the organization to finally see us win a World Series. That’s the one goal when you start and I finished with a World Series. Like I said, the biggest disappointment of my career was losing the ’73 World Series in seven games.