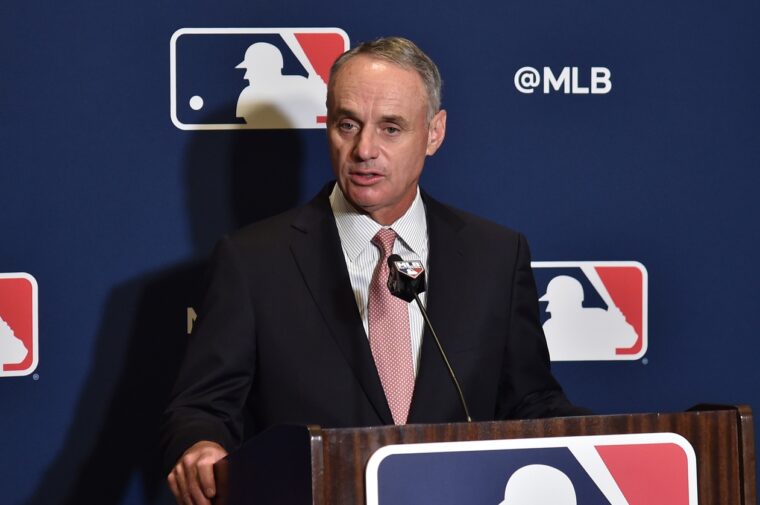

Last weekend, MLB presented the Major League Baseball Players’ Association (MLBPA) with a proposal to delay the start of spring training and the upcoming season by one month. The stated reasons were to allow for an easing in the rise in COVID cases in both spring training sites, Florida and Arizona.

Then, with the season starting in late April, according to many experts COVID cases should be down all over, making for safer conditions for everyone involved. Makes sense, right?

Only, as is typically the case when these two sides attempt to agree on anything, nothing makes sense. MLB’s offer included a 154-game season with full pay, and the universal DH that would provide for more high-paying jobs. Sounds like a steal for the players, the kind that would make Rickey Henderson proud. But, there were strings attached.

There was no guarantee that all 154 games would be played, since rainouts and possible COVID interruptions would have to be shoe-horned into a compressed schedule (with normal, not regional travel). This could impact statistics, that could influence spending on next year’s free agent class.

The owners also wanted expanded playoffs in the offer, a concept the union rejects on the premise that teams will not be as motivated to spend on players. So, the proposal was rejected, there was no counter-offer by the MLBPA, and once again, the sides came off as children arguing in the back of their parents’ station wagon.

The “good” news is that the failure to agree on last weekend’s proposal will likely result in the on-time start of spring training, and a full 162-game schedule (COVID permitting). That’s what we want as fans, right? However, our potentially full season comes at a high price.

First, no one even knows some of the rules under which the season will be played. That’s unfathomable.

We are two weeks from the opening of camps, and the league and its players do not know whether or not there will be a DH in the National League.

Imagine if, in mid-July, NFL teams did not know if there would be twelve players on the field on each side, or the current eleven. Or, if NHL teams, two weeks before the start of camp, did not know if there would be six skaters and goalie or the current five skaters and a goalie. MLB is embarrassing itself with this situation.

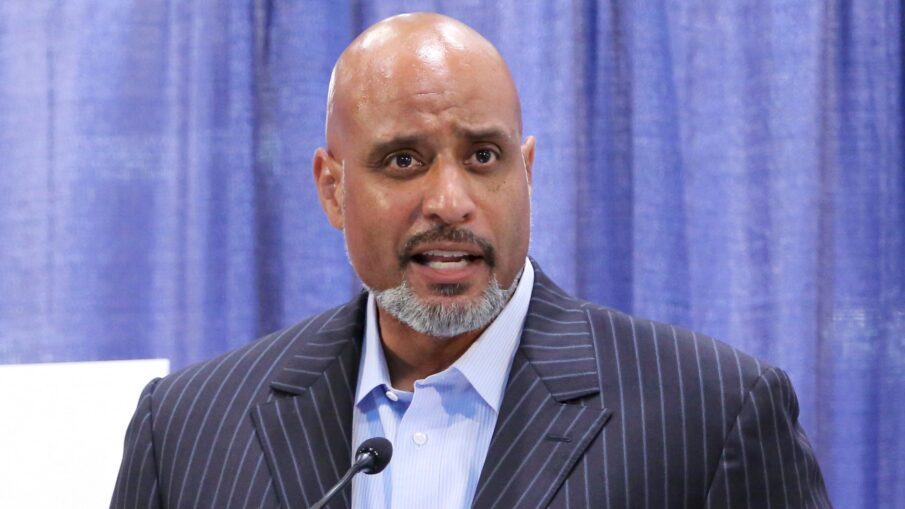

The other price to pay for our (hopefully) full season is the upcoming (after this season) renegotiation of the collective bargaining agreement (CBA). The two sides can’t agree on the rules of play, or how many teams should qualify for the postseason. How are they going to agree on the overall economic structure of the game?

A lockout, or strike, appears to be a certainty after the season. It will be yet another public relations hit for a sport that is losing young fans, and airing its dirty laundry publicly on a routine basis.

How did these two combatants get to this point? History tells the story. As we know, those who do not heed the lessons of history are condemned to repeat it. Let’s take a look at the history of labor relations in MLB.

Prior to the 1970s, the owners held all the cards. Players were bound to their teams, and teams could pay the players what they felt was reasonable when contracts ran out. Players had two choices. Take it or leave it. Ralph Kiner told the story of being given a pay cut after leading the league in home runs. He was told the team finished last with him, and it could do so without him. In the 1970s, the players began to push back.

1972: The players went on strike for the first time. The issue was the owners’ contribution to the pension fund. The owners refused to give in, hoping to damage or break the union. The strike was settled in 13 days, with the players getting what they wanted. In total, 86 games were lost at the beginning of the season. The games were not made up, and teams played different total numbers of games.

1973: Owners locked out the players in spring training over the issue of salary arbitration. The result was a new CBA that included salary arbitration to be decided by a neutral arbitrator. Spring training started and no games were lost.

1976: This was the big one. Union lead Marvin Miller challenged the reserve clause that bound players to teams, and he won. Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally became the first free agents. Owners angrily locked the players out of spring training, but matters were resolved in March and no regular season games were lost.

1980: With the CBA about to expire, players went on strike in spring training, canceling the last week. Further labor strife was avoided, temporarily. Free agent compensation remained an open wound.

1981: The players went on strike in June and two months of the season were lost. The issue was free agent compensation. The agreement reached allowed for teams losing a free agent to select a player from a pool of unprotected players (this cost the Mets Tom Seaver in 1984). The union accepted that although the compensation system would have somewhat of a drag effect of the desire to sign free agents, the drag would be modest.

1985: The players went on strike for two days in August. The issues were the pension fund and salary arbitration (both repeats).

1990: The owners locked the players out of spring training over free agency and arbitration. The season started a week late, but all games were played.

1994: This one was baseball Armageddon, when the players went on strike in August and the game was shut down until the following April. At one point, President Clinton had both sides at the White House, and they still could not reach an agreement. That’s how deeply the animosities ran.

There have been on-and-off labor disruptions in baseball for 50 years. It’s really quite amazing. The people change (Bowie Kuhn, Peter Uberroth, Fay Vincent, Marvin Miller, Don Fehr, Tony Clark), but the rhetoric and mistrust remains the same.

This year, the two sides can’t agree on the rules of play. None of this bodes well for the next CBA. Some players and owners have talked about how they’re prepared to “burn it all down”.

On one hand, with all of the self-inflicted wounds baseball has endured, it’s current popularity (though declining) is incongruent with its checkered history. On the other hand, you have to wonder how many times the game can keep coming back.

Will the next labor issue (if there is one) relegate the sport to the least popular of the “big four”? Maybe. All we can do is hope that cooler, more logical heads prevail and that MLB finds a way to avoid further damaging its own institution.