There are certain organizations whose mere mention of their name conjures up an image. If you were asked to list some of the greatest Yankees of all-time, you’d come up with Ruth, Gehrig, DiMaggio, Mantle, Mattingly, Jeter. Hence, their nickname: The Bronx Bombers. With the exception of Whitey Ford, Roger Clemens (asterisk included) and one phenomenal season from Ron Guidry, the Yankees are celebrated for hitting.

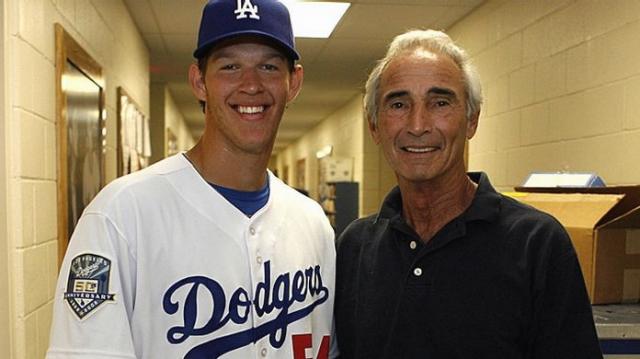

Since moving to Los Angeles, the Dodgers have become identified with turning out great pitchers seemingly every decade. From Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale in the 60’s to Don Sutton and Andy Messersmith in the 70’s to Fernando Valenzuela and Orel Hershiser in the 80’s to Kevin Brown in the late 90’s and now Clayton Kershaw, some of the most dominant starters of the last half century have worn Dodger blue.

The Giants storied history includes power hitters. Four players with over 500 HR’s have played for them. For over a century it seems like some of the most dominant hitters of their era have been Tigers: Ty Cobb, Hank Greenberg, Al Kaline and Triple Crown winner Miguel Cabrera. Philadelphia fans are regarded as some of the rudest and most obstinate in baseball. But is that just a reflection of the gritty in-your-face style of their team? Jimmy Rollins followed in the footsteps of John Kruk and Lenny Dykstra who followed in the footsteps of Larry Bowa.

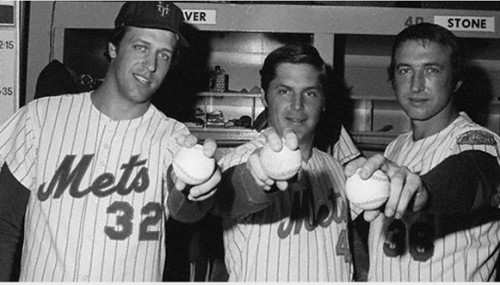

And what about the Mets? We’ve had the reputation of great pitching. And deservedly so. From 1967 through 1984, the Mets had three starters – Tom Seaver, Jon Matlack and Doc Gooden – win Rookie of the Year honors, more than any other team. Add to the mix Jerry Koosman finishing 2nd for ROY in 1968, an ERA champion in Craig Swan in 1978 and the fact that Nolan Ryan was one of ours, it’s easy to see why the Mets were known pitching. In 16 seasons, 1969 through 1985, a Mets pitcher won the Cy Young award four times.

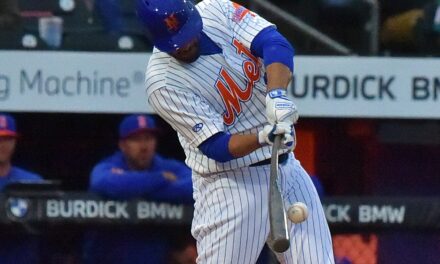

What about now. Is that label still apropos? Do fans and executives still look at Flushing with envy? Does anyone ask rhetorically, “How do those Mets keep doing it?” We clearly know how to turn out great pitching with lots of promise and potential. But is that where it ends? Producing talented young arms is one thing. Keeping them healthy is something else.

What about now. Is that label still apropos? Do fans and executives still look at Flushing with envy? Does anyone ask rhetorically, “How do those Mets keep doing it?” We clearly know how to turn out great pitching with lots of promise and potential. But is that where it ends? Producing talented young arms is one thing. Keeping them healthy is something else.

Granted, arm injuries are more common than ever, but lately it appears the Mets have dealt with more arm injuries than most. A few days ago fans shook their head disgustedly when learning Zack Wheeler would be gone for the year. Wheeler going down comes on the heels of Matt Harvey returning from his Tommy John surgery. This follows Josh Edgin, closer Bobby Parnell missing 2014 with TJS, Jon Niese hurt in 2013 and back to Johan Santana in 2010. We can blame Dan Warthen and Terry Collins and trainers all we want, but this isn’t necessarily a new trend for us. We’ve seen this before.

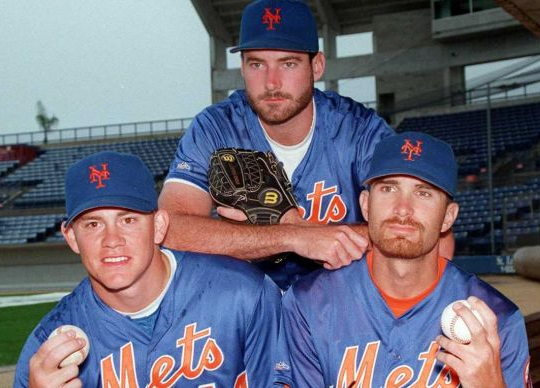

In the mid-90’s, Generation K was supposed to close out the 20th century in dominance akin to Seaver, Koosman and Matlack. Of course, it didn’t happen.

Bill Pulsipher was the first of the trio to arrive. In 1995 he made his debut and between the minors and the majors, the 21 year-old tossed 218 innings. As soon as the season concluded he underwent Tommy John and missed all of ’96 and most of ’97. He would only make 29 more starts between 1998 and 2005 before retiring at age 32.

Jason Isringhausen, the second member of the elite Generation K, was impressive. In the second half of 1995, he went 9-2 with a 2.81 ERA. The following year, the injuries came and didn’t let up. Rib cage, bone spurs, torn labrums and three arm operations between late 95 and 98.

Paul Wilson, the Mets number one pick, was the highest touted of the three. Despite his unorthodox delivery and poor mechanics, Wilson was ordained to be the Mets ace for many years. However, his delivery was never adjusted to reduce stress on his arm. He made 26 starts in 96 before injuries also ended his career.

Generation K didn’t go on to become Seaver, Koosman and Matlack. Instead, they became a low point in Mets history. And fodder for others teams to make jokes about.

One can even go back earlier. Before he made his major league debut on April 7, 1984, Dwight Gooden was larger than life. A legend. A lock for Cooperstown. Those of us who witnessed Doc in those days were overwhelmed with blue and orange pride that a guy this talented, this gifted, and so young pitched on our team. In his first three years, Doc was 58-19 with a 2.32 ERA. He fanned NL batters at an alarming rate, leading the league with an 11.4 K/9 his rookie year.

As we all know, his inner demons derailed his promising career. But one must also take into account his overuse. In 1985, Gooden threw 276.2 innings. Only one pitcher since has surpassed that many innings, knuckleballer Charlie Hough. Experts calculate that between the majors and minors, Doc threw 10,000 pitches before turning 21.

So while our storied history is chock full of great pitching and some of the best pitchers in the game, we’ve also dealt with our fair share of unfortunate bouts with career threatening and season ending arm injuries. It comes in unpredictable ebbs and flows, but one thing we’ve learned is that no matter how bleak things may appear right now on the injury front, this too shall pass.