Thousands of baseball books have been published. Millions of baseball stories have been told, every one of them starts with the same basic understanding: two teams, nine innings, balls, strikes, runs, hits and errors. Along the way there are various twists and turns ending in perfect games, no-hitters, walk off home runs and everything in between.

No two games are the same, but many are alike. They all come back to the final out. Strike three. Game over. But what happens when a game goes on and on and on … with no apparent end in sight? Then, when the moment seemingly arrives, hope is dashed by improbability. There was a major league game like this. It was played on July 4 (and July 5), 1985. This is the story, as told by those who played, reported, broadcast, watched and witnessed it.

Extra innings changes everything. The game of baseball is redefined. To score is to win. To err is to lose. Strategy is discarded. Position players become relief pitchers and relief pitchers are pinch runners, and occasionally hit home runs.

On Independence Day 1985 at Atlanta Fulton County Stadium, the New York Mets and Atlanta Braves played 19 innings, the equivalent of two baseball games (plus one inning) including two rain delays totaling two hours, five minutes, 29 runs, 14 pitchers and 43 players, 155 official at bats, 115 outs, 615 pitches, 46 hits, 23 walks, 22 strikeouts, five errors, 37 stranded base runners, six lead changes, a cycle, two players were ejected and 25 years later the most memorable moment was recorded by the losing pitcher Rick Camp.

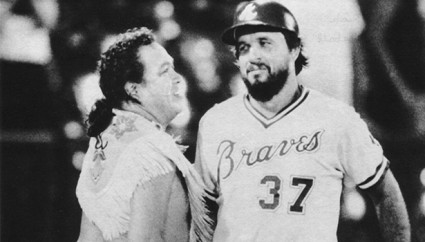

Camp was drafted by the Atlanta Braves in 1974. He grew up on a farm in Georgia, went to school and played ball in Georgia, drove a pickup truck and the team agreed to give him a tractor as part of his deal. Now he was going to pitch for his hometown team. Camp was close to living his dream.

“To hit a home run in the big leagues — that was my dream,” said Camp. Prior to signing with the Braves he hit a lot of home runs, all of them as a designated hitter at West Georgia University where he attended college.

By July 1985, the odds of Camp seeing his dream come true seemed gone. He had 10 hits and a career batting average of .060. “He couldn’t hit his way out of the cage when he’d take BP,” said former teammate Paul Zuvella.

Camp had been moved to Atlanta’s bullpen. The chances of him even getting an opportunity to bat would take, I don’t know, maybe a couple rain delays, a lot of pitching changes and extra innings. Good luck with that.

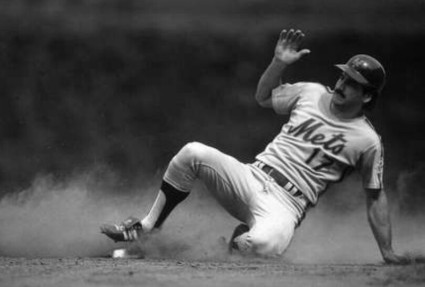

The Mets arrived in Atlanta on July 4th weekend, grumpy. The team was slumping, winning three of their previous 11 games when rookie Len Dykstra dug in to lead off the game after an 84-minute relay delay. Most of the sellout crowd was still in the ballpark.

Sporting a golf ball size wad of tobacco in his left cheek, Dykstra choked his pine tar covered bat about six inches from the handle. He weighed 155 pounds according to the Mets 1985 media guide. He was 30 at-bats into his major league career.

Back in New York, Mookie Wilson, the Mets regular center fielder in 1985 was watching from a bed in Roosevelt Hospital, one day removed from arthroscopic surgery on his right shoulder to repair torn cartilage.

Dykstra dropped a bunt past Rick Mahler. Glenn Hubbard charged from second and bare-handed the ball to Bob Horner at first. Dykstra, in typical hard-nosed style, stumbled over the base, nearly colliding with umpire Jerry Crawford before being called out.

After Wally Backman legged out an infield dribbler, Keith Hernandez stepped to the plate. Mahler fired to first. Backman slid back safely. Mahler persisted, trying again … and again … and again …

Pete Van Wieren doesn’t own a Ouija board. He has no psychic powers. He has never been to a tarot card reading, but he does have an amazing sensory perception on matters related to the diamond. “At the rate this game is going the big 5th of July fireworks show will be presented right after the contest,” he said as the pickoff attempts continued like a broken record.

Mahler finally caught Backman leaning too far. As Crawford signaled Backman out, the Met second baseman slowly climbed to his knees and stared out at Crawford from underneath his helmet. The long give-and-take seemed to last longer than the 84-minute rain delay.

After Hernandez lifted the next pitch into left-center field for a double, Gary Carter grounded a single into centerfield. The ball took two hops and stopped dead in the rain-soaked outfield grass. Braves centerfielder Dale Murphy raced through puddle, scooped up the ball and fired it back to the infield. After a Darryl Strawberry single, advancing Carter to second base, and a George Foster walk to load the bases, Mahler struck out Ray Knight to end the inning.

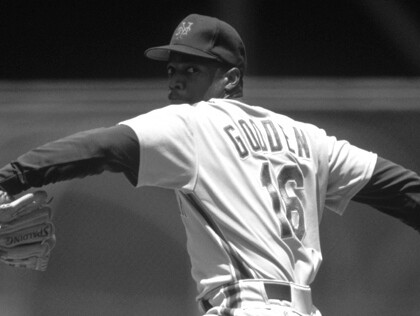

A tall, thin, 20-year old Dwight Gooden was on the mound for the Mets. He was pitching on three days rest for the first time during the 1985 season. He would go on to win 24 games with a 1.53 ERA in 276 innings pitched. In 35 starts, Gooden pitched 16 complete games. His season performance cinched the Cy Young Award, claiming 120 votes, almost twice as many as John Tudor of the St. Louis Cardinals, who finished second (21-8).

Claudell Washington led off the Braves first inning with a triple. The 44,947 in attendance were on their feet. One pitch later, Rafael Ramirez grounded out to shortstop, scoring Washington. It took the Braves four pitches to tie the game.

Gooden followed by walking Murphy on four straight pitches, prompting Carter to zip halfway out between home plate and the mound to settle Gooden down.

Gooden walked Horner on four pitches; eight straight balls.

Terry Harper dug in and Gooden shoved a fastball on the inside corner at the knees for strike one. He sent Harper back to the bench on three pitches. It was as if Gooden pushed some internal on/off button.

“Just three years ago he was pitching to high school kids,” said the late Skip Caray. “My goodness, just think what that must have been like?”

Rick Cerone had missed three weeks due to a sore shoulder. He was activated two days earlier, but hadn’t played in a game since his return. His first at-bat came after a long rain delay against Gooden. Could the cards be any more stacked against the 31-year old Cerone?

“He probably said, ‘Thanks a lot!’ when he saw Gooden out there,” said Caray sarcastically. “He hasn’t played in a month.”

Cerone slashed the first pitch from Gooden to Mets first baseman Hernandez. The ball caromed off his midsection and he bare-handed a sidearm throw to Gooden covering first to end the inning.

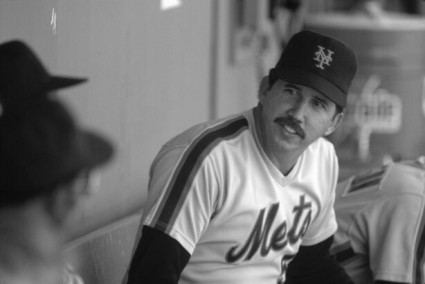

“Back in the ‘70s, Atlanta had one of the worst infields in baseball – but there were a lot of bad infields in the old days,” said Hernandez. “I never liked fielding in Atlanta because it was so hot and everything baked. I always had to do a lot of gardening there, but by the ‘80’s, it was a very good infield.”

The rain returned in the third inning and Terry Tata stopped the game. Two nights earlier in San Francisco, Tata was informed by Major League Baseball he would the acting crew chief for the series in Atlanta, replacing Harry Wendlestedt, who was ill (Wendlestedt did not return to umpire until July 18).

“I took a redeye off the west coast and arrived in Hartford, Connecticut, spent some time with my wife and then took a flight from Bradley Field and arrived in Atlanta at 5pm,” remembers Tata. By the time he arrived at Fulton County Stadium it was already raining.

The Atlanta Braves employed two full-time groundskeepers and an estimated 25 part-time employees to help on game days. Sam Newpher, now the groundskeeper for Daytona International Speedway, was the head groundskeeper at Atlanta Fulton County Stadium in 1985.

Newpher stayed in close contact with the National Weather Service at the Atlanta airport. The weather service could pinpoint the time and location of the incoming storm and its relation to the stadium.

In the press box the media were already playing weatherman. “Everyone working at the ballpark lives in different parts of the city, so it’s not at all uncommon for someone to call home and see if it’s raining in that part of town,” said Van Wieren. “Then you start hearing, ‘well it’s not raining in Dunwoody!’ Then Skip will say, ‘Well, let’s go up there and play.”

Newpher watched as the second rain storm soaked the tarp.

“All of the drainage was surface drainage which drains off to the outside edge (of the field) into two surface drains,” he said. “It was a turtle shell type mound with the center of it being about 25 feet behind second base. Keep something in mind, if a tarp is on the field and you dump the tarp, you’re taking a couple thousand gallons and just going plop in one spot,” he said.

Van Wieren watched the rain fall from the Braves press box. He glanced at his scorecard, then the stadium clock and back to the field. He took a deep breath and exhaled, well aware of how late this game was going to end.

“The team wasn’t very good and sellout crowds were very rare,” said Van Wieren. “We had a sellout crowd that night and the team would do everything in their power to get that game in so they could get the gate.”

When play resumed 41 minutes later, Mets manager Davey Johnson announced he was taking Gooden out to avoid risk of injury. It marked the first time in 27 starts dating back to Aug. 11, 1984 that he had failed to go six innings. Gooden, unhappy, retreated to the Mets clubhouse and began drinking.

The Braves took their only lead of the game, 8-7, scoring four runs in the bottom of the eighth inning. But the Mets tied it in the ninth. By the time the New York Mets and Atlanta Braves began extra innings the calendar read July 5. Still, fans moved to the edge of their seats. Not in anticipation of a win, but the post-game fireworks.

When the Mets came to bat in the 12th inning, Hernandez was a single away from the cycle. He had doubled in the first off Mahler, tripled in the fourth off Jeff Dedmon, homered in the eighth inning Steve Shields.

Hernandez would be facing Terry Forster. He needed his brother, who was home in San Francisco. Hernandez dashed back to the Mets clubhouse, called the operator and asked for an outside line.

“He was my good luck charm,” said Hernandez. “He always came down on West Coast trips. When we left San Francisco he’d come with me to San Diego and L.A. – and I always killed San Diego and L.A.”

Ironically, eleven years earlier on September 11, 1974, as a member of the St. Louis Cardinals, Hernandez pinch hit against the Mets in a 25-inning game at Shea Stadium. “That was my first year,” remembered Hernandez. “I pinched hit in the ninth off Harry Parker and Dave Schneck robbed me of a home run.”

The Cardinals eventually won, 4-3, after seven hours, four minutes and 25 innings. The Mets went to the plate 103 times and the Cards with 99 plate appearances and a major-league record 45 runners left on base. The game ended at 3:13 a.m., the longest game played to a decision without a suspension.

Hernandez singled off Forster to complete the cycle. Superstition rules.

Van Wieren stared at his scorebook. Nothing good could come in the 13th inning, maybe that’s why most scorebooks have 12 innings he thought. “Once you run out of innings in your scorebook it’s improvise time,” he said.

The Mets took a 10-8 lead in the 13th inning. Finally the end was in sight – finally. To his left, Van Weiren’s wife Elaine and two sons (Jon and Steve) sat, waiting for the fireworks.

All Tom Gorman needed now was three outs. After a leadoff single by Rafael Ramirez, the Mets left hander struck out Dale Murphy and Gerald Perry. One more out. Gorman zipped two strikes past Terry Harper. One strike left. Let the fireworks begin. Harper obliged, lining a two-run homer off the left field foul poll to tie the game again.

“I just looked over and they had their head down like, ‘we’re never gonna get out of here,’” remembers Van Wieren.

“You wondered where it’s going to end,” said Caray, remembering Harper’s home run in an interview years earlier. “When (Rick) Camp hit his (in the 18th inning), you figure, we’re going to go on forever. Once is amazing. Twice is incredible. I’ve never seen anything like it in my life and I never think I will.”

The Braves broadcasters weren’t the only ones wondering.

Paul Zuvella was called up just a couple weeks before the July 4th game. His high school buddy Chris Hopson flew in from Milpitas in the Silicon Valley, south of San Jose, California to visit Zuvella and catch a game.

“That was the first game he had come to,” said Zuvella. “Poor guy, he was one of the very few remaining at the end.”

Zuvella was inserted in the sixth inning and faced five different pitchers in seven plate appearances – sidearm pitcher Terry Leach, Jesse Orosco, Doug Sisk , Gorman and Ron Darling – going 0-for-7.

“That, I do remember,” he said. “I remember hitting the ball hard. I hit some line drives right at people. I’m thinking, ‘How unfair is this?’”

“Pitchers tend to have an advantage in that type of game,” said Zuvella. “That’s why they keep throwing the zeros up. It gets a little tougher offensively as the game goes on. You start to think, is this game ever gonna end?”

Both teams put up zeros in the 14th, 15th and 16th innings. In the 17th inning, with nerves frayed, Tata called strike three on Strawberry. As he walked away, Strawberry “had some choice words” and Tata ejected him. “I still see the pitch today when they show it on ESPN Classic. It didn’t look like a bad pitch.”

As Strawberry walked back to the dugout, Mets manager Davey Johnson jogged toward Tata. The argument heated quickly.

“When Davey Johnson gets in my face and I turned my hat around backwards so I could get right in his kisser,” remembers Tata. “As I am looking over his shoulder there’s a digital clock along the first base line and it reads two – five – seven. It’s 2:57 in the morning and I say to Johnson, ‘It’s three o’clock in the morning, everything looks like a strike.’”

Tata ejected four managers, coaches or players in 1985, two of them within 60 seconds.

“The one thing you don’t put in your mind is the hope that it will end,” revealed Tata. “It will end naturally. You can’t root for a guy to hit a home run or driving in the winning run. You’ve got to block that out of your mind and concentrate on the game. Once you start hoping for that it’s going to detract from your overall sense of the game and your job.”

The Mets regained the lead, 11-10, in the 18th inning on a sacrifice fly by Dykstra.

Again, all Gorman needed was three outs. Again, he retired Perry. This time he shut down Harper. One out remained – pitcher Rick Camp. Mets pitching coach Mel Stottlemyre was taking nothing for granted and paid Gorman a visit. Stottlemyre warned Gorman about Harper now he was warning him, don’t make the same mistake. Don’t take Camp for granted.

Gorman registered two quick strikes on Camp. One strike left. Let the fireworks begin – please let the fireworks begin. Gorman fired a forkball on 0-2 and, like Harper five innings earlier, Camp obliged, hitting one over the left field wall to tie the game.

“As soon as it left the bat you knew it was gone,” said Tata. “That just cut your legs off at the knees.”

“That certifies this game as the wackiest, wildest, most improbable game in history!” yelled John Sterling, then a Braves broadcaster on WTBS.

“You’re really certain it’s going to end with Rick Camp at the plate,” said Van Weiren. “When Skip talked about it he said he never saw me get animated in the booth. But when that ball was hit I literally jumped out of his seat and put my hands on top of my head and said, ‘you gotta be kidding me!?’”

Jay Horwitz joined the New York Mets as public relations director in 1980. He was in his fifth year with the team. “I was in the press box,” said Horwitz, who watched most of the extra innings with then Mets scouting director Joe McIlvaine. “I had my binoculars, and I remember looking at the expression on Danny Heep’s face, it was the most incredulous look I’d ever seen. I remember thinking, ‘this game is never, ever going to end.’”

One year later, in 1986, the Mets were involved in a 16-inning marathon game against the Houston Astros, a game that decided the National League Championship Series.

When Billy Hatcher homered off the foul poll in the 14th inning at the Houston Astrodome to tie the game, Horwitz started having flashbacks of Atlanta. “It was the same kind of feeling,” said Horwitz. “You think you have the game won, you’re going to the World Series, they tie the game. We had enough fortitude to come back and win that game. But outside of the rain delays it was almost a duplicate game.”

Jonathan Leach grew up in metropolitan Atlanta and had been a Braves fan since 1973, captured by the Hank Aaron chase. He was home from college for the summer. He fell asleep as the game weaved through extra innings until “the early morning hours, when my brother burst into my room and woke me up to tell me they were still playing,” said Leach. “I saw Rick Camp’s home run which may be the most improbable event in the history of baseball.”

Hundreds of miles north in New Rochelle, New York, Jonathan Falk arrived home from a party at 10 p.m. and turned on the television. “I turned on TBS to find out how they’d done, figuring if I was lucky I might catch an inning,” wrote Falk, a lifelong Braves fan. “They were still playing. I was glued to the set. The Rick Camp homer was probably the single most amazing thing I’ve ever seen in 43 years of baseball watching.”

“That was the most unbelievable part. No one expected that,” said Ken Oberkfell, a Brave in 1985 and the Mets Triple-A manager today. “I mean, I have a better chance of flying an airplane than he (Camp) did of hitting a home run, and there it went. I remember I was in the clubhouse figuring the game was over, but when I saw the home run I came running back to the dugout.”

When asked now if he remembers the pitch Camp said, “I would say it was a fastball. I mean, heck, I had a zero point something batting average. There wasn’t anyone else to hit. I was just trying to make contact.”

As he rounded third, Camp was smiling as he met Tata halfway between home and third base. “You SOB, I was only kidding,’” said Tata.

“Even after I got out of baseball, every time I’d see him he’d just point to left field and laugh,” said Camp.

The Mets scored five runs off Camp in the top of the 19th inning.

“When you’re involved in a season like that and you get into one of those games you really don’t have the same concern over who wins,” remembers Van Weiren. “If you’re in a pennant race you do. If you’re 30 games out, you don’t really care. Sure you’d like to win the game, but if they don’t it’s not going to impact the pennant race. So when you get to a point in a game like that you’re just ready for it to end.”

Not the fans. As the Braves mounted another rally in the bottom of the 19th, scoring two runs, the fans began to chant, “We want Camp!”

“If we have to rely on me to hit a home run to win a game, we’re in bad shape,” said Camp. “I’ll always remember the homer, but it was a hard thing for me to do that and then go out and suck up a loss.”

“Go ahead hit another one out, we’ll pay ‘til noon,” said Tata.

This time Camp was facing Ron Darling, the Mets seventh pitcher of the game. Darling hadn’t made a relief appearance since his freshman year at Yale. The Mets were so certain Camp would not hit another home run, they began untying their shoes in the dugouts, equipment was being packed away.

“I remember the last pitch,” said Camp. “It was a high fastball I swung and missed. Struck out. You get a fastball from here up (motioning from his chest to eye level) it looks like a watermelon. I was trying to kill it.”

Strike Three. Game Over.

“This was the greatest game ever played – Ever,” said Howard Johnson.

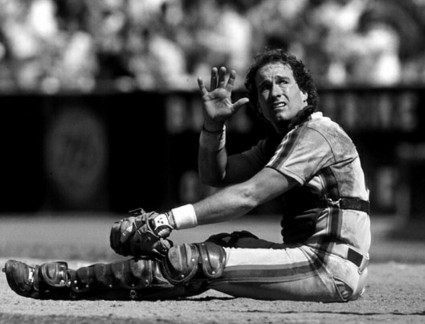

“That was the greatest thing I’d ever seen,” added Bruce Benedict, Braves’ catcher, ” The tough thing about it was that there were a lot of lifetime memories in this game and we lost it. It’s hard to put those things in perspective. It was embarrassing.”

“That was the most bizarre game I ever played in – bizarre and fascinating, depressing and great, thrilling and boring,” said Darling. “It was all of those things mixed in. It would have been a story but Rick Camp made it a big story. I’m just glad I got my name in the box score.”

“I thought we were going to win it after that,” said Dale Murphy. “I couldn’t believe it. It’s the most unbelievable thing I’ve ever seen. I’ll never forget that home run. I’ll never forget this game. I can’t explain this game. I’ll be feeling this for the next week.”

“Thrilling,” “fascinating” and “great” didn’t describe the experience for Carter, who was playing his first season in New York. He caught the entire game, handling seven New York pitchers and catching 305 balls.

“The game took a toll on me,” said Carter. “It was worse than catching both games of an afternoon doubleheader because of the rain (delays). My body was aching and throbbing.”

“Do you know what it’s like to be playing baseball at 3:30 in the morning?” asked Dykstra after the game. “Strange man. Real strange.”

“I saw things that I’ve never seen in my major league career,” added Hernandez.

Like Camp hitting a home run … or Knight who left 11 runners on base in his first nine at bats, including three times with the bases loaded.

According to the Elias Sports Bureau, no other continuous game in major league history had ended so late. Prior to July 4-5, 1985, the previous latest game was completed at 3:23 a.m. in Philadelphia when the Phillies beat the Montreal Expos 6-1 on Aug. 10, 1977.

Rick Aguilera never saw it, any of it. Aguilera was sent home in the 13th after Johnson’s go-ahead home run. ”When I got to the room, I turned on the TV and saw the game still going,” he said. “I thought it was a delayed broadcast. I couldn’t believe it when they said it was tied.”

Aguilera went to bed. His roommate Sid Fernandez arrived a few hours later and Aguilera asked if the Mets won. ”He said we did,” remembers Aguilera, “but he also said I wouldn’t believe it.”

“When the game ended we were all so exhausted we were just thinking, we gotta get out of here and get ready for tomorrow … I take that back, we gotta get ready for today.”

Gorman was credited with a win. It was then that Gorman found himself in a save situation with the Mets ahead 10-8 in the 13th inning. He lost that lead. And then another.

“To give up a homer to the pitcher in the 18th inning is totally embarrassing,” Gorman told the media a couple hours later. “I learned I can’t take anything for granted. I felt like I saw it all tonight. I should have saved the game; I should have won the game; I should have lost the game. It’s the weirdest thing I’ve ever seen.”

”There’s not one thing you can say you feel at that moment,” added Gorman. “It’s not like pitchers don’t hit home runs; they do. I’m not trying to take anything away from Camp, but you know if you hit the ball good here, it’s going to go out. I’d never pitched at three in the morning, but guess they’d never hit then either.”

Newpher and the grounds crew headed back to the field after arriving at Atlanta Fulton County Stadium at 8am. “One of the very few people left in the stands was my wife,” he said.

“What are you still doing here?” he asked.

“I came to see the fireworks,” she said.

Fireworks? It’s four in the morning. But the Braves were in no position to negotiate. There were 8,000-10,000 people still in the stands, delirious and jacked up on coffee, waking up their children for the fireworks. Then, there was WTBS, who sold sponsorships for the July 4th fireworks show.

“There was a great concern about whether the fireworks show would or would not go on,” remembers Van Weiren. “Ted (Turner) had gotten the station (WTBS) to sell a separate post-game that would include the fireworks. Once the game ended there was going to be a commercial break, we’d come back on the air and televise the fireworks.”

Braves television broadcaster Ernie Johnson was beside himself about the whole concept. Fireworks on TV? Come on, who’s going to watch that.

“We kidded about that,” said Van Weiren. “Ernie (Johnson) said ‘what are we supposed to say when the fireworks go off? Do we just sit there and go ‘Ooooh! Ahhh!?’ It was going to be a strange deal.”

Van Weiren said as the game went deeper into the night, there were a lot of questions about “whether they were going to do the fireworks,” he said. “We got the word that the fireworks were gonna go because this was a sold program on TBS and they were going to get the sponsored money.”

So, at 4:01 a.m. on July 5 the July 4th fireworks display began. For nearly 10 minutes the skies over Atlanta thundered. Bright colors lit up the night followed by the sounds of massive explosions. The roar hit a crescendo with a finale so intense, Atlanta resident Vivian Williams jumped from her bed.

Like many others living in the Atlanta suburbs, Williams believed the city had come under attack. The phones lit up at the police station. The Atlanta Journal-Constitution later reported “residents of Capitol Homes and other areas near the stadium called the police to complain that their neighbors, the Braves, were disturbing the peace.”

Williams told the police “setting off fireworks at 4 a.m. is inappropriate and ill-advised.”

Meanwhile, calls were pouring in to the Braves public relations office. Some came from fans who left before the end of the game and were angry that the fireworks display was not postponed until another date, he said. Other calls were from neighbors of the stadium who called the Braves to complain about the noise.

“We went back to the hotel and the USA Today was already under the door,” remembers Horwitz. “That’s always a bad sign, when the USA Today beats you there.”

Chip Caray, then home on college break, remembers his father stumbling in as the sun rose. He figured it was a late night with the guys.

“It’s the latest I’ve ever stayed out in my life and not done something I was ashamed of,” Skip said.