Jeff McNeil and J.D. Davis were two of the best hitters in baseball last season.

Hyperbole? You say maybe. I say no.

By the catch-all offensive metric Weighted Runs Created+ (wRC+), which quantifies runs created and normalizes for ballpark and overall MLB run-scoring environment, JD Davis ranked 22nd in all of baseball last season among players with 450+ plate appearances. That’s better than Mookie Betts, Kris Bryant, Ronald Acuña Jr., and DJ LeMahieu, among others. Jeff McNeil ranked 10th. That’s better than all those names, plus Juan Soto, Freddie Freeman, Jose Altuve, and even Pete Alonso.

They both did it with impressively balanced ability – for McNeil, a miniscule 13.2% strikeout percentage (17th in MLB) led to a lot of balls in play, but he somehow blended his ability to get the bat on the ball with impressive power – of all players last season with a 13.2% or better K%, only 2 had more home runs, and both of them, Yuli Gurriel and Alex Bregman, played for the sign-stealing Houston Astros.

In Davis’ case (in-depth breakdown here), an uncanny ability to hit the ball hard, 90th percentile leagewide in exit velocity per Statcast, coupled with an uncanny ability to hit the ball often, with a .307 average that ranked 2nd on the Mets, led to an offensive juggernaut that helped turn the Mets’ season around with increased playing time.

Defensively, though, the stories are a little different. While McNeil showed a multipositional competence that make him look like a truly complete MLB star, Davis struggled in both the infield and outfield by both the eye test and the advanced metrics:

Per @fangraphs , ultimate zone rating (UZR) /150 for third basemen in 2019 (minimum 150 innings):

Jeff McNeil: 19.4 (1st in MLB)

JD Davis: -6.1 (48th in MLB)For left fielders:

Jeff McNeil: -1.2 (44th in MLB)

JD Davis: -13.9 (75th in MLB)Who should go where?#LGM #LFGM https://t.co/GE40LTL0YN

— Corner Three (@corner3sports) February 19, 2020

That brings us to the big decision for new manager Luis Rojas and the Mets this season – where should these guys play? The Mets are rightfully giving Davis ample opportunity in camp to play third, to get a better look at the situation.

It makes sense – outside factors seem to be driving both guys to the infield. The inability to count on any innings from Jed Lowrie, coupled with the likely many off days for 37-year old Robinson Canó, could lead to quite a few games where the Mets would count on Jeff McNeil to hold down second base. Meanwhile, the increasing complexity of the Mets’ outfield situation, with the (hopeful) return of Yoenis Céspedes and potential starts in the corners for Dominic Smith, could make it even harder for Rojas to consistently get Davis’ excellent bat in the lineup if he can’t play a solid hot corner.

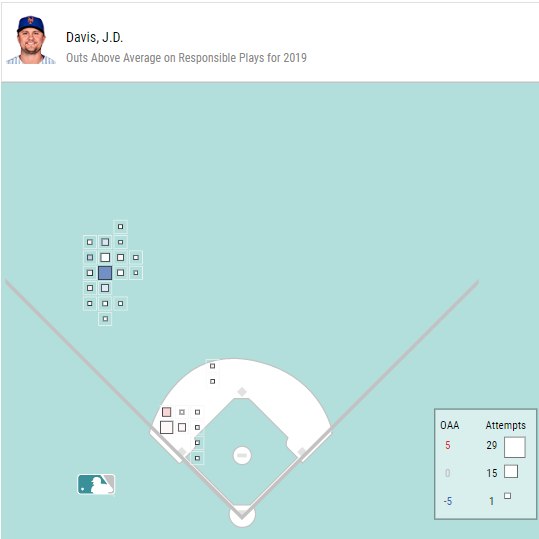

In limited time last year, Davis was almost respectable at third. Yes, he had some series hiccups, especially early in the season, and issues with lob throws and lack of confidence. However, the evidence suggest he was even worse at getting outs in left, even if the errors didn’t stand out as much. Looking at Statcast’s Outs Above Average visualization, things look a lot better at third than his absolute adventure in left field:

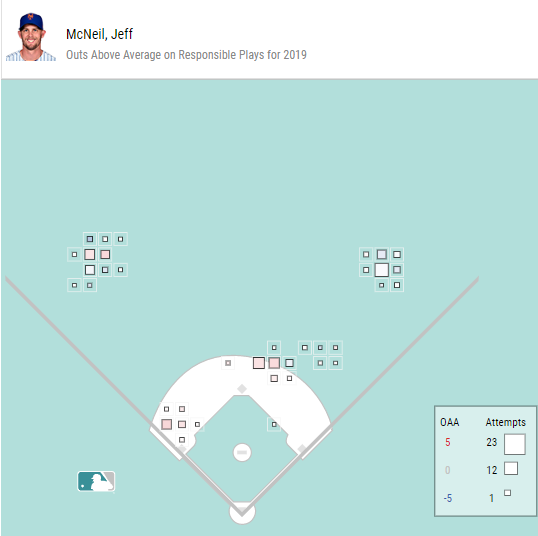

The Squirrel, on the other hand, simply got outs everywhere he was asked:

So, if Canó’s at second, and Davis and McNeil are both starting (which I personally expect to be the most common situation for the Mets this season), what’s the optimal alignment?

At the end of the day, it probably won’t be hugely impactful on the Mets’ season trajectory as a whole, and it’s probably good to get both guys innings at both positions to keep them fresh at both in case of necessity.

However, this brings up what I find to be an interesting thought experiment in baseball competitive advantage – in general, is it better to have a good defender in left and a poor one at third, or vice versa?

There haven’t been too many studies done on this specific question, but we can take some pointers. This study by StatsByLopez in 2013 suggested “differences in the defensive abilities of shortstop and third basemen appeared to have a larger impact on the game in 2013 than in 2003… the importance of strong defensive infielders has grown.”

The classic sabermetric concept of the “defensive spectrum”, according to Bill James, is 1B-LF-RF-3B-CF-2B-SS-C, "with the basic premise being that positions at the right end of the spectrum are more difficult than the positions at the left end of the spectrum. Players can generally move from right to left along the spectrum successfully during their careers.” The implication here is that third base defense is more valuable due to its relative higher level of difficulty.

I asked Brett Zaziski, former MiLB player/MLB analyst, for his take, and he told me: “In general I’d put the poor fielder in left field every time, because third is way harder than the outfield and has the same range to cover in play at every ballpark. That’s as opposed to left field, where there are fields like Fenway, and really any AL East stadium, where there is a lot less ground to cover. The increase in fly balls leads to more home runs, but not necessarily meaning it is harder to play in the outfield. Line drives are really the hardest to read in the outfield. Additionally, the growth of the shift makes the third basemen need to be more versatile.”

I tend to agree. Take another look at JD Davis’ Statcast visual – at third, he’s essentially playing short sometimes with the fluidity of today’s infield positions.

Overall, it’s likely these two offensive studs will move all around the diamond as the season goes on, when injuries, pitching styles, and all sorts of butterfly effects that inevitably come with a Mets season come into play.

Or, maybe, one day soon, the DH will come and make all of these little baseball complexities moot.