There are 10 players eligible for induction into the Hall of Fame who have the Mets on some portion of their resume. Next up is a beloved pitcher who made New York one-stop on his major league odyssey.

Even if his plaque isn’t in the Hall, the home run should be. The result of the at-bat in 2016 at Petco Park against James Shields was Bartolo Colón’s career moment, becoming the oldest player to hit his first homer, it didn’t make his career by no means—a career that crossed centuries and spanned generations.

Colón began as a relatively slender fireballer and ended as a rotund craftsman. He was an All-Star in 1998 and an All-Star 18 years later. Colón’s longevity is a testament to his physical prowess and his ability to adapt and evolve. He pitched for 11 different teams, starting with Cleveland in 1997, tossing 3,461.2 innings and tallying 2,535 strikeouts until his final stop in Texas in 2018.

His peak from the late 90s to the mid-2000s culminated in the AL Cy Young Award in 2005. The ace of the Los Angeles Angels, he had a 3.48 ERA and 157 strikeouts while going 21-8.

He struggled through the rest of the decade before finding success with the Yankees and A’s. The Mets acquired Colón before the 2014 season having already surpassed age 40.

For three years in New York, Colón was a veteran leader on a young rotation—eating up innings and often putting them in a place to win games.

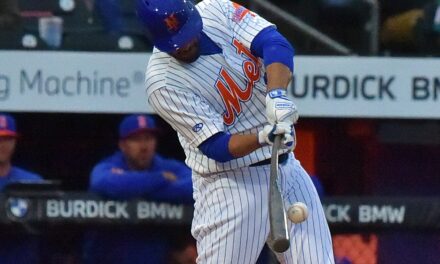

And, oh yeah, this day was pretty fun too. Colón was a good pitcher, but also entertaining—one of the most interesting figures in baseball. ‘Unique’ is thrown around loosely, but it was appropriate for Bart.

6 years ago today, Bartolo Colon hit a home run.

— Mike Mayer (@mikemayer22) May 7, 2022

The Case for

Longevity isn’t a significant factor when weighing Hall of Fame credentials. Colón’s, though, is especially impressive when considering how he changed his style over the years. His statistics, while given the amount of time it took to achieve them, are more impressive when compared to others throughout history and compared to the time in which he did them.

Of all the hurlers born in the 1970s, nobody threw more innings, and only one had more wins. Colón is second among that group in strikeouts. Like all pitchers on the mound in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Colón’s prime came in a time slanted heavily toward offense. Another disadvantage was the rash of injuries pitchers encountered trying to keep up, and modern medicine hadn’t figured out how to fully address them.

As advanced metrics have taken over justifiably, traditional statistics like wins and strikeouts don’t carry the same weight they once did. However, Colón’s achievements become more impressive when viewed in the context of his contemporaries. Wins, especially, are more a reflection of the longevity he displayed than the success he had. His 247 wins rank him among the top 50 in major league history and the most among all Dominican-born players.

The Case Against

The big mark on Bartolo’s resume is his 50-game performance-enhancing suspension in 2012. He also was suspected of PED use after surgery two years before. The trend appears to be a little favorable in terms of steroid use, but known users are still on the outside looking in. That’s especially the case if you’re a borderline candidate at best.

Colón’s 4.12 career ERA is significantly worse than any modern pitcher in the Hall (Jack Morris is the highest at 3.90). A better judge is ERA+, which levels out time periods. But even with that, 106 is slightly above average. However, that’s better than Morris and fellow Cooperstown member Catfish Hunter.

His pitching WAR ranks 113th all-time, just ahead of Dwight Gooden and higher than four Hall of Famers: Morris, Hunter, Bob Lemon, and Dizzy Dean. But while that might seem like a case in Colón’s corner, Morris and Fisher’s resumes are enhanced by postseason performances, while Dean and Lemon had far shorter careers.

Final Thoughts

If the Hall of Fame was for uniqueness and recognition that athletes of this sport come in all shapes and sizes, then Bartolo Colón must be included. If being inducted is a measure of excellence, which it is, then that’s a different story. Watching Bartolo pitch, field, and hit was a joy. He is unlike anyone in baseball history, and he has historic merit. He’s also one of the better pitchers of this century for a career that somehow began even before this century. But by the standards, this is for the museum in Cooperstown, he falls short.