We are entering the era of big data. Like it or not, it’s everywhere. There’s data for everything, and everyone is using it to be more efficient in whatever it is they’re doing. The same applies in baseball. While I don’t always agree with some of the advanced statistics out there, I find many of them quite useful. After playing/coaching/teaching the game for 30+ years, many of the traditional stats were ingrained in my brain. It’s all we ever used or cared about while we played.

It wasn’t until 5-6 years ago that I started to embrace many of the advanced statistics to determine how a player is performing. Now one of my hobbies is to look back and see which awards may have changed (MVP and Cy Young) through the years if advanced stats were taken into consideration.

Stats aren’t the only thing changing about the game. As a young hitter, I remember being taught to swing down on the ball to create backspin (which created lift)–now they teach launch angles and swinging more upwards, ala Ted Williams, to create more lift.

The game is changing, it’s being played differently and has to be measured differently than in the past. Many of the traditional stats that we use have been around for more than 100 years when it was a much different game. While it may have taken a while for me to cozy up to some of the stats being used today, there was one stat I always felt was the biggest crock in the game. Oddly enough, it is considered a traditional stat. That stat is the Save.

I’m not going to get into a history lesson about how the Save stat came about because it can easily be researched if one chooses. I will tell you that the major argument against the Save, one that I absolutely agree with, is that somewhere along the line, managers started coaching to the stat. Managers started to reserve their best relievers, now called closers, for the ninth inning of games in order for the player to compile more saves, rather than use the player when they are most needed (in high leverage situations).

I’m not completely sure why it started, but it was sensationalized as closers became these dominating figures that would come marching (sometimes running) in from the bullpen, usually to some very aggressive music. It was like a WWE wrestler getting ready to enter the ring. All the theatrics probably came from watching the movie Major League, because in the climax of the film Ricky Vaughn comes out of the bullpen to the song “Wild Thing” with all the fans going bananas in the stands. Kudos to Lou Brown for bringing Vaughn in during a high leverage situation.

When you think about it, the only place where the Save truly matters is in the major leagues. In little league, high school and college baseball, Saves don’t get any hype. Their seasons are relatively short in comparison to the big leagues and every win matters. It forces coaches to use their best available pitchers in high leverage situations because they want to win the most games possible. This doesn’t mean the best reliever can’t come in the ninth inning—if that’s the high leverage situation, that’s when they should be used.

It just means that you use your best reliever when you need them the most—seventh, eighth, or ninth inning. If the opposing team is threatening to take the lead, or your team is up by one run in the eighth inning and going to face the heart of their lineup, isn’t it wiser to use the best reliever in those situations so the opposing team has lower odds of scoring runs and potentially winning the game?

It’s funny because when major league teams are in the playoffs with their asses on the line, you will see them operate in this fashion (completely opposite of what they would most likely do in the regular season). Managers call on the best pitcher available (sometimes even starters on short rest, although this is unlikely to happen in the regular season ) in order to stop opposing offenses in their tracks. Why? Because they know it gives them the best chance to win, and that’s the ultimate goal after all.

So if the teams know that if they use their best relievers in high leverage situations, it gives them a better chance of winning, why does anyone care about the Save stat?

I can’t answer question…tradition, maybe? Because that’s the way we’ve always done it? All I know is that I have grown to hate the Save. However, the good news for people that feel the same way as I do is that there finally seems to be a stat which properly evaluates relief pitchers.

That stat is the Goose Egg (this time, I will give you a brief history).

The Goose Egg was created by Nate Silver over at fivethirtyeight.com. He posted a very in-depth explanation of the stat which can be found here, but I will give you the basics so when you look at the Mets relief pitcher breakdown below, there is some context.

The stat was developed to try and find a better way to analyze relief pitchers. The stat was named after, you guessed it, Goose Gossage. It was a blend of troll and praise for Gossage as he has gone on tirades in the past about hating the Save statistic, but he also happens to be the all-time leader in Goose Eggs.

But what exactly is a Goose Egg? (I’ll refer to them as GE for the remainder of this post).

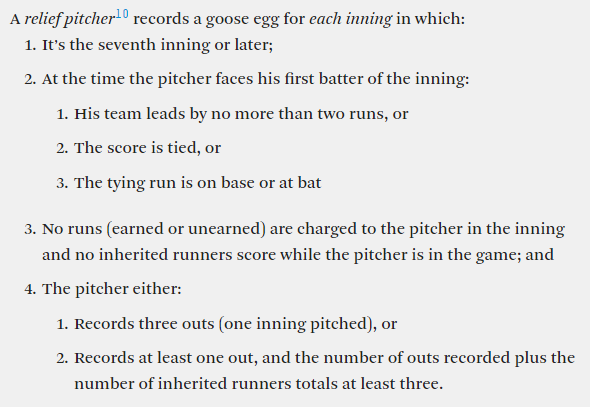

Simply stated, any time a pitcher is in a high leverage situation (7th inning or later) and they fail to give up a run (earned or unearned), they’re credited with one GE (a player can receive multiple GEs in a game). If they give up a run in the situation (inherited runs count), it’s a Broken Egg. There’s a conversion rate, and gWAR (Goose WAR) also associated with it GEs. Here is a graphic from the article on fivethirtyeight.com (linked earlier) that show the actual criteria for a GE:

Keep in mind that while many organizations still seem to be managing their bullpens around the Save, at least in the regular season, there is one manager that has embraced the GE: Gabe Kapler.

Now this being a Mets website and all, we have to take a look at how the Mets do with this stat. We will look at 2018 GEs to see how Mets relief pitchers performed last season, as well as how their two new acquisitions in Edwin Diaz and Jeurys Familia performed. Then we will take a look at some of the all-time numbers from Mets relievers.

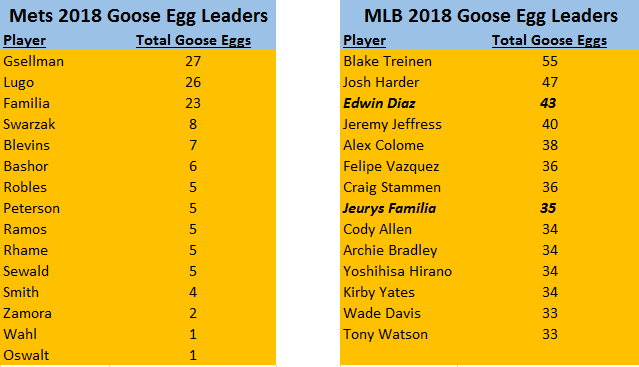

First, here is a side-by-side comparison which shows the Mets relievers from 2018, and the top 15 GE leaders in the MLB from 2018:

The Mets will head into the 2019 season with two of the top 15 relief pitchers in total GEs from 2018 in Diaz and Familia. There is a good chance that they can both end the season with 40+ GEs. Rob Gsellman and Seth Lugo were also just outside the top 15, and Mickey Callaway will be looking for them to repeat that type of performance in 2019.

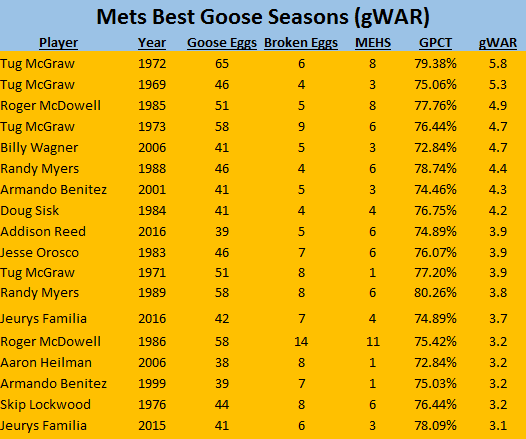

Now let’s take a look at some of the Mets best relief pitcher through the years according to gWAR and total GEs:

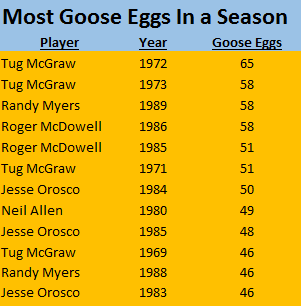

As you can see from the list, Tug McGraw had three of the best seasons ever recorded by a Mets reliever according to gWAR. He also holds the top two spots for GEs by a Mets pitcher in a season. This is probably a combination of him being put into more high leverage situations (as relief pitchers were used differently back then), and his ability to get out of innings without allowing runners to score. Edwin Diaz ended the 2017 season with 40 GEs and a 3.5 gWAR—had it been with the Mets, it would have been one of the best seasons by a relief pitcher in Mets history.

Here is also a list of the Mets all-time GE leaders (top 10):

Little surprise here seeing Franco and McGraw as the top two in Mets history. Familia also cracks the Mets top 10, and he will be able to add to his total now that he is back with the Mets—keep in mind that he will also be used as a setup man for Diaz, which could put him in more high leverage situations than Diaz (and it should probably be the other way around).

It’s also worth noting that there are also some former Mets ranked in the top 25 for GEs all-time (not shown): John Franco (589), Tug McGraw (521), Fransisco Rodriguez (430), Billy Wagner (421), Jesse Orosco (416), and Randy Myers (404).

There you have it. It may not be a perfect stat, but I think it does a better job of evaluating relief pitchers based on their job description—coming into games during the later innings, usually in high leverage situations, and not allowing the opposing team to score.

Special thanks to John Edwards for helping me track down some of the GE data.