I was an overprotected child growing up … a lot like our current batch of Mets pitching prospects. I was sheltered, coddled … had strict limits on my bathroom minutes …

My mom bundled me up in way more layers than I needed and I had a daylight curfew, yet somehow all her caution couldn’t shield me from the effects of growing up on 98th Street in Corona. Like inmates in a prison, the neighborhood kids found a way to get to me. All it takes is one friendly kid that your parents approve of (every neighborhood has them — they look clean and polite on the outside), and all of a sudden your house is at the center of a dirt-bomb war with the 99th Street goons and your flustered mother is pulling you by the ear wondering where you learned such language.

We didn’t like cowards on my block. If you had a beef with someone you stood up and took your licks. The older kids made sure of it — sometimes they’d even break out boxing gloves and make a main event of it. What we didn’t tolerate was guys who’d run away. We made a point of making it worse for them. We used to play this game called “Hunter” where we’d count off by age (younger kids first – easier to catch) and take turns being hunted down and roughed up by the rest of the mob. Kind of like an all-against-one Ringolario only way more violent.

Rules were you had to stay in a two block radius (backyards and fence jumping were permitted), you could not go inside, nothing permanent or “in the face” and … no other rules. Well this one kid would always duck into his house before we’d get to him.

Eventually we got tired of it and three of the biggest kids walked right into his house and dragged him out while that same nice kid tried to explain to this boy’s mom how he’d cheated because he participated in beating everybody else up. Eventually she tired of our diplomat and chased us away swinging her apron, whereupon she commenced to beating him way worse than we would have.

The lesson? Nature abhors a coward, especially in New York … which brings us to the subject at hand. The Mets operate in baseball’s largest market the last time I checked. They are sitting on this stockpile of pitching and have hesitated to pull the trigger on a trade. They’ve been assailed as overly cautious and hesitant, cowardly even. We could use outfield help, maybe a shortstop, yet it almost feels as if our front office is afraid to take a shot. Are they yella? This sort of thing doesn’t fly in New York — apparently these guys didn’t get the memo.

Then again, the last time they traded a pitcher for a position player they sent Collin McHugh to the Rockies for Eric Young Jr., not so good … so maybe they have good reason to be reluctant. But somehow I don’t think the reason behind Alderson’s aversion to trading from his stockpile is fear of failure or the affection he feels for his prospects, although I can picture him following Brandon Nimmo around wiping his nose and bundling him up on chilly mornings. Brandon has that effect on people — he’s got a face you want to make hot cocoa for.

Anyway, it is well known that this front office ascribes to methodologies that rely on tons of data. For this reason I think chalking up their reluctance to an overly cautious disposition makes no sense. I doubt Alderson is afraid of a little trade-market roughhousing, and he doesn’t seem too worried about fan backlash neither.

So what is it? Why so gun shy? Well, first off, lets consider who we’re dealing with. In Paul DePodesta and Alderson we have an economist and a corporate lawyer who have a penchant for data. My sense is there has to be some sort of measured rationale behind the reticence.

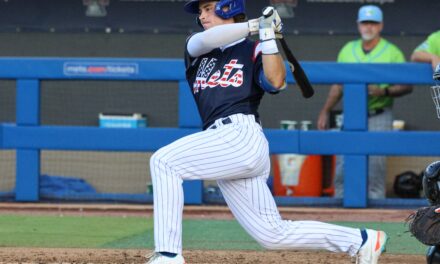

As before, we need look no further than Sandy’s copious rhetoric. The phrase that stands out is “cost-control,” I keep hearing it referencing their stockpile, its inflection conspicuous and loaded. There appears to be something special about cost controlled players as it were, in contemporary baseball vernacular … Something intrinsically exceptional about them beyond their understood affordability.

You hear a lot about how it’s tough to part with a cost controlled player if you aren’t getting one in return (Anthony Rizzo for Andrew Cashner in 2012 was just such an example). So, the notion that you could trade someone like Montero and maybe another equally cost efficient prospect for Alex Gordon or Jose Bautista becomes unlikely because you would not only have to pay Gordon (or Bautista), but you would also lose a cheap controllable asset in Montero — the expense becomes twofold, thus prohibitive.

Another hang-up when it comes to trading from the Mets surplus is assigning a market value to it. I mean if someone asks me how much I want for my corn cob Elvis sculpture, it helps if I have an answer. So what are these prospects actually worth?

The current free agent pool is remarkable in its dearth of top-shelf options. Whether it’s due to qualifying offers or creative ways of signing promising youngsters to long term deals, there appear to be fewer and fewer elite talents hitting free agency. How does that reflect on this discussion? Well, if a spigot runs dry because water is being diverted upstream, you’ve got to go upstream to get the water. If free agency is offering fewer options, then sources further up the pipeline become more lucrative, more valuable. It speaks to supply and demand.

It is difficult, however, to accurately appraise prospects on one end of the pipeline when the drop in volume (and quality) of talent trickling out the the free agent end hasn’t quite triggered a market reflex yet.

This uncertainty is why the Mets have been so reluctant to trade from their surplus. The hope for Alderson and his accomplices is that one more winter of buyers scouring a depleted free agent pool will bring shoppers back to his stockpile at a sizable markup. It’s a waiting game.

So it has nothing whatsoever to do with reticence. Like everything involving the Mets these days this is all about money and assigning value to controllable assets.

Both Epstein and Alderson covet cost controlled young players in a landscape where free agency has become unreliable and prohibitive. One GM is stockpiling position players while the other is stockpiling frontline pitching. Personally I’d go with pitching but it will be interesting to see how this little staring contest plays out. Another game we used to play on my block was flinch …